Welcome to my 500th post.

To celebrate I’m going to take it a bit easier for the rest of this month and just do some trips down Memory Lane.

Today in particular, I hope regular readers remember the piece I wrote in 2018 about Marion Cran because 100 years ago last week she became the first person to do a radio broadcast about gardening. The first of her Gardening Chats went out on 2LO, the forerunner of the BBC, on August 6th 1923 for which she was paid the princely sum of 5 guineas.

Marion Cran was a really interesting character, now almost totally forgotten but she’s not the only overlooked gardener I’ve written about so see how many others you recognise – or might have missed – from these much earlier posts…click on the links to be taken straight to them!

And of course it would be remiss me of me not to remind you that I publicised Barbie’s interest in gardening long before the film came out

So do you remember …

these other women gardeners who’ve featured in the blog in the past?

At the top of the pile, so to speak, is Queen Caroline, wife of George II and according to Lucy Worsley “the cleverest queen consort ever to sit on the throne of England”. Caroline was also a very keen gardener, who used her garden at Kew as a political tool. She commissioned unusual buildings from William Kent, including Merlin’s Cave which was peopled by wax statues of liberal philosophers and theologians, and a rustic Hermitage which was lived in by Stephen Duck the poet.

Slightly lower down the social pecking order was Elizabeth Montague, one of the bluestockings. Luckily she was a very keen letter writer, and her correspondence reveals a lot about her gardening interests. She worked with Capability Brown at her country home, Sandleford Priory in Berkshire, a site now under threat of development. She enjoyed visiting country houses and estates but she often comments more on their landscapes and gardens when she does on their architecture. “The beauties of a palace are not so enchanting as those of a garden or park.”

But it’s really not until the 19th century that less aristocratic women really begin to come into their own as garden makers. One of the most interesting is Louisa Lawrence, whose “second-rate” suburban villa garden in west London was nothing like it sounds from Loudon’s classification in The Gardener’s Magazine for July 1838

Instead it was an eclectic mix of every style under the sun, stuffed with artefacts as well as rare plants and much praised by everyone who saw it. Mrs Lawrence was an expert gardener, or maybe a shrewd judge of garden staff, because she exhibited regularly at London shows winning many prizes. Her son was to become President of the RHS perhaps inspired by his mothers example.

If you like the idea of mildly eccentric subjects do you remember Lady Dorothy Neville, who was, as young woman “found in ‘a compromising situation’ in the summer house”. Married off quietly she later became a society hostess and a founder of the Primrose League set up in memory of her friend Disraeli.

More importantly from our point of view she built up the largest collection of exotic plants outside Kew at her Dangstein estate, where she also had an avian orchestra. And if you’re not sure what an avian orchestra is you can see and hear one on a video clip in the post.

We’re used to reading about Gertrude Jekyll, being a great plantswoman, writer and designer, but she had another side entirely. We tend to imagine her as a dumpy but formidable old lady with dark clothes reaching to the ground and walking in a garden with the aid of a stick. But that is not how she saw herself and there was definitely another side to her: “I ought to know I am quite an old woman. But I can still – when no one is looking – climb over a five-barred gate or jump a ditch.”

She also had a real thing about cats and formally invited them to tea with her favourite children for whom she had designed a playhouse. See the post or her book Children and Gardens [1908]for more information.

Gertrude stuck – with the exception of Boismoutiers in Normandy – to designing gardens in Britain, and running a small commercial nursery to supply the plants for her plans. In later life she hardly left Munstead Wood, however, two of her contemporaries Ella and Florence Du Cane travelled the world. They paid for their trips by writing commercially about gardens, most famously in Japan,

They used some of what they saw when they came to make their own gardens at Mountains and Beacon Hill in Essex. These gardens were quickly recognized as interesting and significant and were reported on by Christopher Hussey in Country Life, almost in tandem, in 1925

Wisteria at Kameido, from Flowers and Gardens of Japan, 1908

So far all the women I’ve mentioned gardened for themselves but one woman, Ada Salter, although she struggled a gardener herself, showed the huge social impact gardens can have.

Ada was first woman mayor in London, and first Labour woman mayor in Britain and set out in the early 20thc with a mission to “beautify Bermondsey” one of the poorest and most densely packed parts of the capital. Then, as now, local government was bedevilled with a lack of finance and almost endless squabbles with central government but somehow Ada managed to steer Bermondsey through all that, convert old churchyards into parks, open playgrounds for children and plant thousands of trees.

Another woman famously interested in gardening was the late Queen Mother, Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon. Perhaps that was why in 1968 she was invited to do something unusual. I know that royalty are used to planting trees, shaking hands with all and sundry, opening buildings or events but she was asked to open…

From the guide book to the National Gardening Centre

… Britain’s first garden centre which was sited on the edge of Syon Park, one of London’s remaining great private estates by its owner the Duke of Northumberland. Sh was accompanied on that occasion by the late great Percy Thrower.

I’ve written about him too. First about His rise to prominence from an apprenticeship in the royal gardens at Windsor , to becoming the youngest boss of a council parks department. He stayed in that job in Shrewsbury for the rest of his career although of course he rocketed to fame for his TV shows.

Gardeners World producer Barrie Edgar with Thrower preparing a scene for the programme

from My Lifetime in Gardening

I even managed to include a video clip of the start of Gardening Club which later became Gardeners’ World. That’s covered in a second post along with the story of how Percy fell foul of the BBC’s non-advertising policy for doing some work for ICI and got the boot.

Cecil Middleton, gardening author and broadcaster

One of the reasons that I’m sure Percy was so popular and often referred to as the nation’s head gardener was because he didn’t lose the common touch. There were other early broadcasters who had the same appeal. Mr Middleton, for example who hosted the first regular gardening programme on the radio in 1931 which became popular because as he said “there was nothing brainy about them”. He then went on to start the first TV gardening programme in 1936 and even the first televised visit to the Chelsea Flower show in 1938.

Fred Streeter

BBC

His successor was the star of his own post way back in 2014. Fred Streeter was another man of the people as well as being head gardener at Petworth for most of his working life. His broad Sussex accent was instantly recognisable, and after his first radio broadcast in 1936 his employer, Lord Leconfield, told him that while he himself was only recognised by the aristocracy “after today the whole world knows you.”

You can also find both of them – and their musical tastes – in the post I wrote in 2014 about gardeners who’ve appeared on Desert Island Discs.

Harry Wheatcroft, cover photo from his book In Praise of Roses, 19xx

They’re there alongside less well-know characters including Roy Hay, Frances Perry, Wilfred Shewell-Cooper, Xenia Field, and Bill Sowerbutts – all of whom were castaways in the 1960s. If you can’t remember who they are go and read the post! There are of course more modern desert island residents who you can check out- but which one of them was the only one to include any pop music?

Amongst the later gardening castaways was the flamboyant rose-grower Harry Wheatcroft and the post about him has proved perennially popular and I still get contacted by readers asking questions about him, his company and the roses he introduced, even though it was written in 2015.

While Most of the gardeners I’ve written about seem to have been genuinely nice people, one 19thc gardener is more problematic!

The unacceptable and acceptable shape of tulips – but do you know which is which or why? from George Glenny’s The Gardener and Practical Florist: Volume 1, 1843

Known as the Horticultural Hornet . George Glenny was a prolific journalist, writer and self-selected arbiter of taste. He was cantankerous with a lacerating tongue and clearly found many of his fellow men irritating BUT at eh same time he was a leading proponent of gardening philanthropy and the driving force behind the Gardeners Benevolent Society [now Perennial].

He crops up in several posts but the one that I found the most interesting to write is about his involvement in setting the standards for flower shows, which in turn led plant breeders to try and change the shape and other attributes of many well-known flowers.

But Glenny is not the only 19thc gardener I’ve written about.

Seated gardener with a shovel, undated, by William Egley, 1798–1870, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

There some still comparatively well known like Peter Barr, the daffodil king, Edward Cooke the rockery designer, the Rev Henry D’Ombrain the gladiolus and rose specialist,Henry Eckford the man who popularised sweet peas, , Michael Rochford the founder of the house plant dynasty, garden designer William Sawrey Gilpin, and plant hunter George Don and his family.

But I think my favourite has to be the rose-loving Samuel Reynolds Hole, Rector of Caunton in Nottinghamshire and later Dean of Rochester. He was not only a great gardener but a great human being . As he recounted in A Book About Roses he was out-gardened by a group of working class rose-growers and in awe of their skill, generosity and openness . It’s a story that might bring tears to your eyes.

There are some interesting 20thc gardening characters too. One of the iconic spaces in 20thc London was the roof garden at Derry & Toms department store, which later became a restaurant and nightclub for Virgin, although its now closed. It was designed by Ralph Hancock who had previously designed the Garden of the Nations at the Rockefeller Centre in New York.

Gardening and Literature: Mr. Clarence Elliott and Sir John Squire at Home.

Illustrated London News (London, England),Saturday, January 11, 1958

from Ashberry’s Gardens in Miniature

There’s a post about Clarence Elliott, a pioneering nurseryman who seems to have been behind the revival of interest in alpine and rock gardening, and is credited by the RHS with being the inspiration for the scree and alpine trough gardens at Wisley.

And having just written that it reminds me that I should have included another woman gardener earlier because Anne Ashberry specialised in constructing miniature gardens, although in a very different style to Elliott. She even made some for the royal family. They might be a bit kitsch to contemporary eyes with their faux ducks and wishing wells but she was good plantswoman and used genuinely miniature plants to her compositions.

from Gardens in Miniature

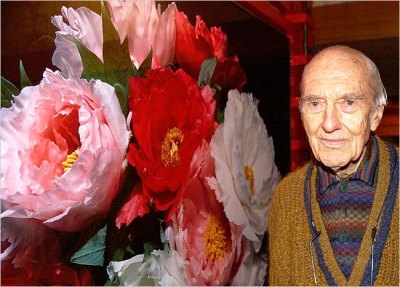

Sir Peter Smithers, in 2003. Credit Karl Mathis/Keystone, via Associated Press

Another forgotten twentieth century whose gardening will outlast his other achievements is the ex-Tory MP, Peter Smithers. He gave up his seat to to work at NATO and then moved to Switzerland where he spent the remainder of his life creating a garden in the mountains and hybridising plants such as tree peonies, magnolias and nerines, and becoming what he said was ” a floral pornographer”.

And there are plenty more less well-known gardeners with interesting tales to tell. You might recall the story of Archibald McNaughton told in a letter to John Claudius Loudon’s Gardener Magazine in 18xx which proved a surprisingly popular piece perhaps because it related to real “ordinary” people who often don’t figure much in our history books. Other even more anonymous gardeners featured in a post about the Cries of London way back in 2018 but over the next few years I’ll do my best to uncover some others!

from James Bishop’s The New Cries of London, c.1844

You must be logged in to post a comment.