If I asked you to think about mediaeval gardens I’m sure a few things would quickly come to mind…. monks, monasteries and herbs and then if you recall paintings you might have seen on Christmas or greetings cards you might remember seeing people – particularly the Virgin Mary – sitting in a walled or hedged garden.

That walled or hedged garden is often referred to as a Hortus Conclusus which is simply Latin for an enclosed garden.

But is it what mediaeval gardens were really like? Is it really a garden style? Or maybe it has symbolic meaning instead?

The first thing to say is that there’s a lot more to the mediaeval garden than is usually thought. Yes, monks, monasteries, and herbs are part of the story but a mediaeval garden was much more than that.

Of course the mediaeval world was very different to ours. Much of Europe was forested or uncultivated, and such wilderness was seen as frightening. Settlements were small and scattered, often centred around defensive sites such as castles or fortified manors, with windows mainly looking inward to courtyards, rather than outwards over the countryside. Villages and estates had to be, by and large, self-sufficient so gardening was largely about food production or basic medicines. Because fields and gardens were liable to incursions from wild animals, outlaws or any attacking forces, they tended to be close to habitation and surrounded with hedges and ditches for protection.

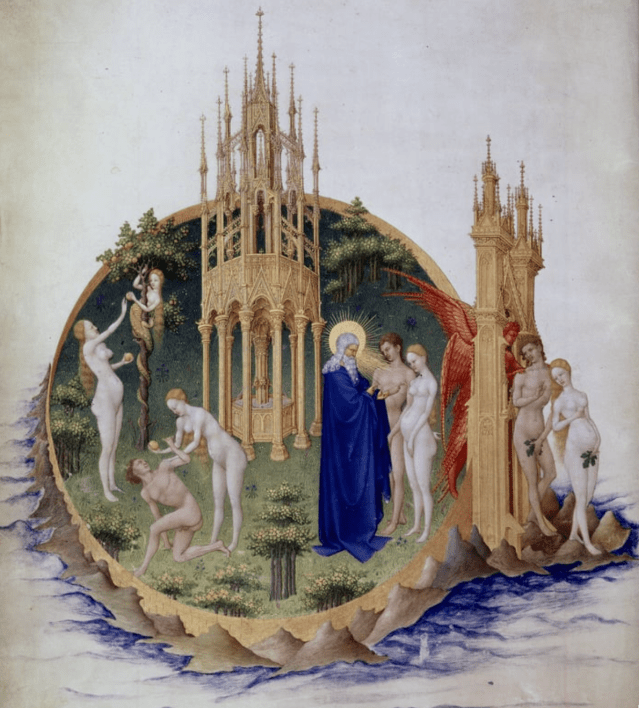

Only a tiny handful of the elite had much leisure time to employ on ornamental gardening and even then there was a very limited range of plants to use and only primitive technology. However we should never forget that, despite the limitations, craft skills were highly developed and mediaeval engineers were able to create soaring cathedrals and churches, carry out large-scale landscaping, and lay out gardens with elaborate designs as can be seen in contemporary images and descriptions. The problem is that although many of these images appear to record gardens quite realistically, showing features such as turf seats, fountains, raised beds, topiary, potted plants, trellises, fences, bowers and, of course, flowers all of which would have been familiar to contemporary viewers, there is more, much more, than just accurate documentation to many of them.

The Hortus Conclusus was not a productive garden, although it appears to share some of the physical constraints, notably being enclosed for protection. Instead it is an ornamental and idealised space, with huge symbolic importance and roots that can be traced back to the Bible.

In part it is the Garden of Eden, but more importantly its imagery links back to the Biblical Song of Songs, one of the most popular and influential of biblical texts during the Middle Ages. The King James version includes the lines “A Garden locked is my sister, my bride, a garden locked, a fountain sealed.”

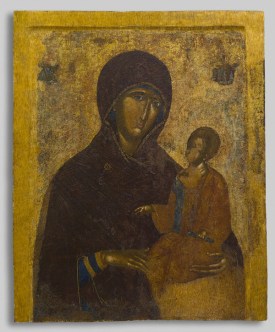

And once you start unpacking what that might mean you have to start suspending modern beliefs and adjust your thought pattern to a very different way of understanding the world. As Penelope Hobhouse says in “The Story of Gardening” Hortus Conclusus is a term “charged with a profound religious resonance that is not easy for us to grasp. It no doubt contained far greater meaning and significance for the mediaeval mind, but even so it remained a complicated concept in a period when Christian beliefs and dogmas, particularly with reference to the importance of the Virgin Mary, were changing and developing.” The portrayal of Mary in this more informal and intimate garden setting is very much a western European development compared with more stilted way she is depicted in eastern Christendom which derived from the Byzantine tradition of icons.

So what does the Hortus Conclusus actually symbolise? We can deduce quite a lot from contemporary texts, so for example, to early Christians the locked garden could be seen as representing the church. Once inside its protective walls or hedges the believer was safe. This association of the walled garden being the church lasted right through until at least the mid-17thc as I showed in an earlier post.

The fountain, which can often be seen in paintings of a Hortus Conclusus represented the waters of life, baptism, and thus membership of the church. It was just one small step from that reference to “the garden locked” being my sister my bride to seeing the Church as the Bride of Christ in a mystical marriage with the Church.

However, as is so often the way, simple ideas and metaphors develop into more complex ones. The hortus conclusus become a feminine space, associated with Mary and the Christ Child and, as the cult of Mary develops, she not only takes centre stage in the garden but metaphorically herself becomes a garden, with the Christ Child growing inside her.

As Professor Liz McAvoy who headed up The Enclosed Garden Project at Swansea University points out the hortus conclusus is also about “unabashed sexuality and desire” with “the enclosed garden as ultimately synonymous with the female body – and the womb it houses: as the female speaker in the Song 5: 4 recounts: ‘My beloved put his hand through the key hole, and my bowels were moved at his touch..’ ”

She goes on to assert that such overt sexual connotations “posed a very real problem” to Christian theologians, notably Bernard of Clairvaux in the early 12thc who had to look for ways to turn it into an allegory of the relation between Mary and Christ, or Christ and the church and humanity. The result was “the ubiquitous appearance of the enclosed garden” as a sacred space which could be interpreted symbolically in several ways.

One significant one was the garden could now be seen as a safe space – replacing the garden as a place of danger that, because of Eve and the serpent, had led to the expulsion of mankind from Eden. The theological complexity is deepened by another verse in the Song of Songs :”Thou art all fair, my love; there is no spot in thee” which then leads on to the idea of Mary’s Immaculate Conception – ie that because she was the virgin mother of God she must, unlike all other humans, have been born without sin.

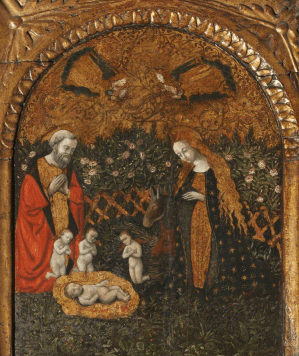

Alongside that, as I showed in an earlier post, is that late mediaeval and Renaissance paintings of the Annunciation often show it taking place in an enclosed garden. There are also a few rare examples of other religious scenes such as the nativity being shown in a garden setting.

That this develops further can be traced through paintings. From Annunciation scenes which have just the single figures of Gabriel and Mary, a new style emerges in Italy, which became known later as a sacra conversatione – a holy conversation piece – akin to the conversation piece paintings of early Georgian England but with religious instead of secular figures. These tend to be informal scenes with saints or angels alongside the Virgin and Child, and sometimes with donors included in the overall setting of a garden too. A good example of how sophisticated such garden scenes can be is found in Gerard David’s The Virgin and Child with Saints and Donor which appears at first glance to be set inside but in fact is set under a canopy, perhaps of a summer house, with a tiled floor. The garden, with its climber covered walls, is clearly there in the background, with the town beyond.

But the garden is rarely seen as a fully planted design, indeed it isn’t always shown in its entirety, or as in the Lochner planting above with any elements of a garden at all apart from grass. Sometimes there are walls or trellising in the background or cutting off side views, and sometimes there is even less visible, perhaps just a turf seat or a few grass tufts to give the impression of a garden.

Nor is it always a tidy, deliberately planted garden. The painting below by Martin Schongauer, who produced many hortus images, makes the garden in the painting almost wild, down to its extremely rustic wattle fencing panels. There are plenty of accurately drawn flowers but they are growing apparently haphazardly.

The picture contains several other visual allusions. Mary is sitting under a cherry tree, a symbol of virginity, and holding a dianthus (meaning ‘flower of God’ in Greek). Dianthus which include pinks and carnations were often included as a rather convoluted reference to the Crucifixion. Their scent resembles that of cloves, and cloves look like little nails and by extrapolation specifically the nails that fastened Christ to the Cross.

But I’ve even found a garden where the artist, Gozzoli, has been deceptive. Although there’s a rose hedge in the background look carefully at what appear to be real grass and flowers under the feet of the Virgin and angels.

The range of plants available for garden use was extremely limited. In the early 9thc the Emperor Charlemagne listed about 100 that should be grown on his estates, and by 1400 Friar Daniel, a London based Dominican record 252 growing in his garden, but many of these were useful rather than ornamentals. However, as can be seen from the margins of many illuminated manuscripts, the most beautiful of the decorative plants were all associated with Mary.

Virgin and Child in the Hortus Conclusus (Left wing of a diptych)

by an anonymous German Artist active in Westphalia

©Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

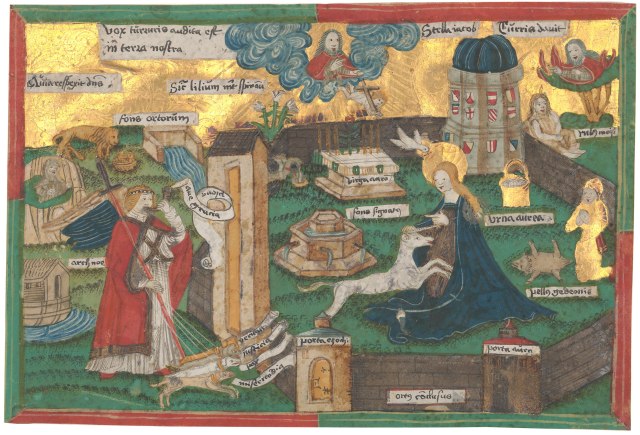

Occasionally there are other garden features or structures which add to the symbolic complexity. Indeed in a few pictures, like the one above, symbolism takes front place. Be warned some of the symbolic connections are pretty abstract!

On the top right is an altar with a collection of what appear to be 12 pointed sticks, one of which has leaves at the top. This refers back to the time when the Israelites were in captivity in Egypt before the Exodus, and Moses had a rod for his work as shepherd. When he assumed leadership of the Israelites his shepherd’s rod became a symbol of his authority as well as being the cause of miracles such as the parting of the Red Sea.

On the top right is an altar with a collection of what appear to be 12 pointed sticks, one of which has leaves at the top. This refers back to the time when the Israelites were in captivity in Egypt before the Exodus, and Moses had a rod for his work as shepherd. When he assumed leadership of the Israelites his shepherd’s rod became a symbol of his authority as well as being the cause of miracles such as the parting of the Red Sea.

There were disputes about which tribe should provide the members of the priesthood for the Israelites so God commanded each tribe to provide a rod which were to be left on an altar overnight. In a sign that it was to be the tribe of Levi, led by Moses brother Aaron, who were to have this honour, their rod “put forth buds, produced blossoms, and bore ripe almonds”. Aaron’s rod had other miraculous powers used to help the Israelites attempts to leave Egypt. Aaron was pitted in magical combat against Pharaoh’s magicians. He “cast down his rod” and it turned into a serpent and although the Egyptian sorcerers rods all did the same Aarons snake gobbled them up! Somehow, and it’s a very convoluted bit of theology, this all became transferred to Christian iconography – to become the blossoming of Mary in the Annunciation.

In the top left is a gateway/tower, another rather bizarre reference back to the Song of Songs: “Thy neck is like the tower of David builded for an armoury, whereon there hang a thousand bucklers, all shields of mighty men.”

How this relates to Mary I’m, not quite sure but it does somehow because the gateway appears in several other Hortus images.

Next comes the Ark of the Covenant, built for Moses during the Exodus and which contained the most sacred relic of the Israelites including the two stone tablets of the Ten Commandments, together with Aaron’s rod and a pot of manna.

It too was adapted by early Christian theologians with Saint Athanasius, linking the Ark to the Virgin Mary: “O noble Virgin, truly you are greater than any other greatness. … You are greater than them all O (Ark of the) Covenant, clothed with purity instead of gold! You are the Ark in which is found the golden vessel containing the true manna, that is, the flesh in which Divinity resides” Later theologians then linked this to a verse in the Book of Revelation identifying Mary as the “Ark of the New Covenant” because she carried the most precious thing in the world the saviour of mankind inside herself, thus becoming the Holy of Holies and the She is ‘the dwelling of God […] with men.”

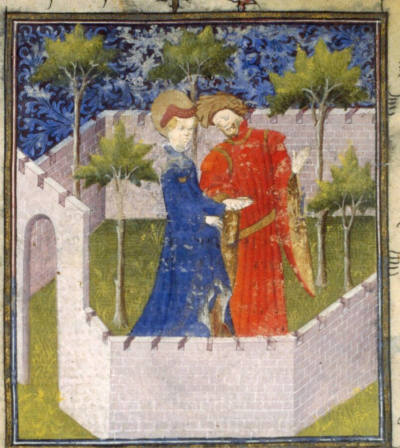

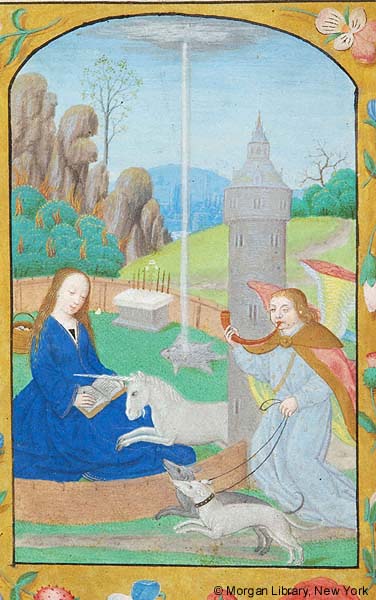

Aaron’s rod also appears in this manuscript image of the Annunciation, which is set in a low walled garden with a wider landscape beyond. However there are some new symbolic elements included too.

Perhaps the least obvious is the greenery that is behind Mary, just outside the wall. This refers to the story of Moses when “the angel of the Lord appeared unto him in a flame of fire out of the midst of a bush; and he looked, and, behold, the bush burned with fire, and the bush was not consumed.” This was interpreted as a parallel with Mary having given birth to Christ without suffering any harm, or loss of virginity.

In the centre of the image is an animal skin – in fact a fleece – being struck by a beam of light. This is a reference to the story of Gideon who asks God for two successive miracles regarding a fleece, first that it should be wet with dew in the morning while everything around is dry, and then that it should be dry in the morning while everything around is wet with dew. Theologically, the striking of the fleece signifies the impregnation of Mary by the Holy Spirit.

The largest element of the landscape is of course the tower. While this may refer back to the tower of David in the Song of Songs, there is another applicable verse “Your neck is like an ivory tower”. By the 12thc the ivory tower has become a sign of nobility and purity and again linked to Mary. The modern meaning of “Ivory Tower” dates only from the early 19thc.

Finally for today, there is the angel Gabriel portrayed as a hunter, blowing his horn and having two dogs straining at the leash. His prey is the unicorn which is kneeling in front of Mary with its head in her lap. A similar set of symbols – and Gabriel as a unicorn hunter -can be seen in the late 15thc German devotional image below.

What on earth is going on?

It’s part of the growing secularisation off the Hortus Conclusus in the 15thc. I won’t say too much more now because as we’ll see in next week’s post unicorns had all sorts of symbolic meaning both in religious and secular terms.

You must be logged in to post a comment.