All that talk of seaweed and photography by Anna Atkins in last week’s post reminded me that, like fern collecting, seaweed collecting was a very big thing in the mid-19thc and taken up by many middle class women as an acceptable hobby – even Queen Victoria indulged.

Who do you think wrote this little ditty?

Call us not weeds, we are flowers of the sea,

For lovely and bright and gay-tinted are we.

And quite independent of sunshine or showers.

Then call us not weeds, we are ocean’s gay flowers.

We are nursed not like plants of a summer parterre

Where gales are but sighs of an evening air ;

Our exquisite, fragile, and delicate forms

Are nursed by the ocean, and rocked by the storms

Read on to find out…

and I suspect that if you’re a lover of great English literature you will be surprised

They may not be the most memorable lines from Jane Austen – yes THAT Jane Austen – but they are included in a chapter of her last novel, Sanditon unfinished when she died in 1817. She tells us that a group were strolling along the beach where “The Miss Beauforts were ecstatic about the seaweed. It was, apparently, Brinshore’ s chief claim to fame ~ and had they seen the sweet seaweed pictures in the shop outside the library? Oh, then they must all come immediately to look at them. Seaweed, the Miss Beauforts insisted, was a very definite attraction at a resort; one could spend happy hours collecting prize pieces; one could trace them or press them and arrange them most artistically.”

Austen’s perception of the gender divide is as sharp as ever, because Arthur, the man on this walk while he” caught something of their enthusiasm” regarded “it as a more scientific pastime.” That was echoed by the fact that they had “just come across a man on a naturalist’s ramble; he had a basket in one hand and a prod in the other; and he was wading out on the low tide to look for more specimens.”

Charlotte one of the main protagonists is torn between the two views. While she understood “how absorbing it must be collecting and identifying all the varieties ~ there are hundreds of them.” she ” herself remained unmoved by the charms of seaweed even when they reached the Miss Beauforts’ shop and were entreated to admire the framed pictures. Dried and arranged carefully under glass, the seaweed appeared now in the form of baskets and bouquets of flowers, set above, below or around a set of obligatory verses in faultless copperplate: Call us not weeds, we are flowers of the sea….”

For more on seaweed albums and pictures see for example When Housewives Were Seduced by Seaweed and Nature Domesticated: A Victorian Seaweed Scrapbook

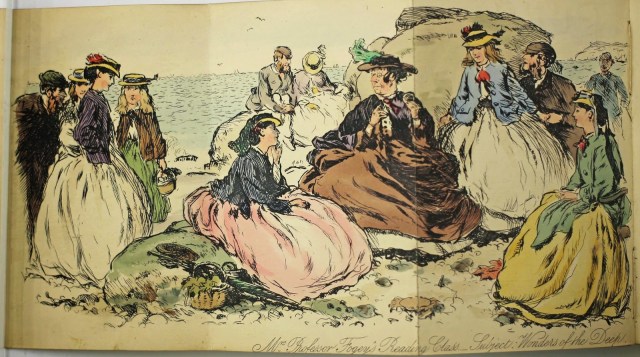

Austen’s characters reflect how the study, understanding and classification of Seaweed was becoming a subject of real interest to scientists in the early 19thc but was matched by an older and more widespread use of seaweed in the decorative arts. Austen was not the only novelist to write of such matters. A more personal note was struck by George Eliot who went collecting with her partner George Henry Lewes and wrote about it in ‘Recollections of Ilfracombe’.By the mid-19thc that gender divide was being challenged, in large part thanks to several pioneering, and now almost forgotten, women who collected and published serious scientific books on the subject rather than just making pretty patterns and pictures. Although they were often portrayed unkindly as in the cartoon below where “Mrs Professor Fogey” is rather dull, forbidding and masculine in appearance, they made a huge contribution to research and popularising a love of marine botany.

These days seaweed is being seen as a potential panacea able to solve many of the planet’s problems. It has great food potential, contributes more oxygen and absorbs more carbon dioxide that all the terrestrial rain forests combined, and derivatives from it could replace many oil-based products. However, to the first serious investigators of marine botany and biology in the late 18th and early 19thc most of that was unknown, and indeed William Harvey, the first man to devote his career to algology – the study of seaweeds – told his teacher he intended “to study my favourite and useless class, Cryptogamia. I think I hear thee say, Tut-tut! But no matter. To be useless, various, and abstruse, is a sufficient recommendation of a science to make it pleasing to me.” although that was written rather tongue in cheek because he did add that in fact there he thought there was plenty of use to be obtained from marine algae. [Memoirs].

Harvey went on to become professor of Botany at Trinity College Dublin and had a great influence on his students and correspondents, and he was generous with his time and advice, making no great distinction between men and women. This was, of course, at a time that women were still formally excluded from almost every scientific institution. It wasn’t until 1835 that the Royal Astronomical Society broke the mould and admitted two women, and even though botany was regarded as a respectable amateur pursuit for women it wasn’t until 1905 that the Linnaean Society accepted women as members.

Despite this, from the earliest years, there were notable women collectors of marine as well as terrestrial botanical specimens. During the late eighteenth century, the naturalist Stephen Hales began assembling a collection for the Princess Augusta, more famous for her garden at Kew than her marine collections, while the Duchess of Portland built up her collection by enlisting the practical assistance of a Mrs Le Coq of Weymouth about whom I can find no further information.

Things begin to change in the early 19thc due to a range of factors. . Steam-press printing made books cheaper and more accessible. Technical improvements in microscopes made them affordable to the middle class, revealing details hitherto invisible to the naked eye to amateur naturalists. But above all it was greatly improved transport links with the growth of the railway network from the 1850s which opened up much easier access to the coast, just as it did to remoter areas on the country which were home to ferns and which led to fern fever.

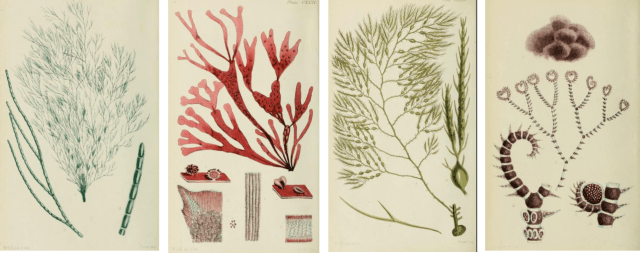

Nevertheless attitudes still took a long time to change and it required the more inclusive attitudes of Harvey and a few others to help women break through into the more hands-on and scientific aspects. Another was Robert Kaye Greville who dedicated his Algae Britannicae. published in 1830, to ” my fair and intelligent countrywomen” to whom “we are indebted for much of what we know upon the subject… To Mrs GRIFFITHS, Miss HUTCHINS, Miss HILL, Miss CUTLER, and Mrs HARE, we owe very many discoveries”

Amelia Griffiths was a vicar’s widow from Torquay and in 1839 she met and became friends with Harvey as well. By then she was already well known in botanical circles and had had a seaweed named after her in 1817. Harvey was later to dedicate his 1849 Manual of British Algae to her, and once wrote “If I lean to glorify any one, it is Mrs Griffiths, to whom I owe much of the little acquaintance I have with the variations to which these plants are subject, and who is always ready to supply me with fruits of plants which every one else finds barren. She is worth ten thousand other collectors.”

Harvey was not the only writer who benefitted from Griffiths’s knowledge and expertise. The Revd David Landsborough’s A Popular History of British Seaweeds , (1849) in the second edition of 1852 cites seven women and six men among the extensive acknowledgements in the prefacei, including her. He calls her the ‘willingly acknowledged Queen of Algologists’. He adds that she had discovered several species during the 1830s and 1840s, although she “did not directly make her work public, being: a lady who, so far as we know, has published nothing in her own name, – but who may yet be said to have published much, as she has so often been consulted by distinguished naturalists, who have been proud to acknowledge the benefit they have derived from her scientific eye and sound judgement.” Later she became the dedicatee of The nature-printed British sea-weeds by Johnson & Croall [1859] Three albums of her speciemns are in the collection of the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter.

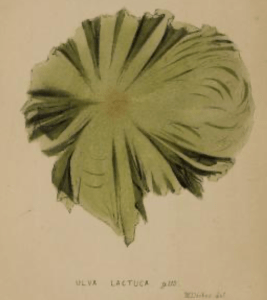

The first woman to publish in her own name was [I think] Elizabeth Anne Allom, author of The Sea-Weed Collector (1841). She opted for local varieties than a more comprehensive study and suggested that ‘the most scrupulously delicate lady may walk with comfort along the beautifully level sands” at Ramsgate and “collect the most interesting specimens of marine vegetation without the slightest danger or inconvenience from damp or cold’. She also wrote Sea-Side Pleasures a children’s books on the subject. Her book is unusual in that the images are not printed but actual specimens of pressed and dried seaweed. Her book is therefore not simply a book about seaweed, but a book of seaweed. [For more on Allom see this blog fromIndiana University.]

One of William Harvey’s early correspondents was Isabella Gifford, from Minehead, whose name he noted among a list of those who had contributed specimens to Phycologia Britannica. She was from a well-connected family with links to several well-known scientific figures although she seems to have been largely self taught. In 1848 she published The marine botanist; an introduction to the study of algology. It was later enlarged in two further editions and was praised in one review for its simple and clear explanatory notes which would “attract new votaries to the study of our marine flora.” Like Allom she did most of her collecting locally saying her aim was to draw attention to the specimens that were constantly available in an area rather than those that were only seen occasionally. [There’s More about Gifford in the Dictionary of Welsh Biography]

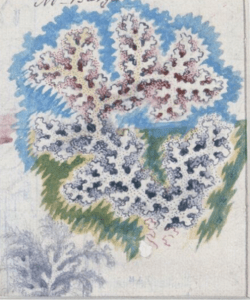

In that same year, 1848, one of Harvey’s books , Phycologia Britannica, or, A History of British Sea-weeds [1846] was given to Margaret Gatty, a Yorkshire vicar’s wife when she was recovering from illness in Hastings. Through it she discovered what was to become her lifelong passion : seaweed. She was then aged about 40 and one of her granddaughters later wrote in her biography that “from that time her interest in the subject never wavered and she kept up her enthusiasm till the day of her death.She collected seaweeds wherever she went and encouraged her friends to do the same; she kept an aquarium and welcomed rapturously any addition to it; and her letters became full of strange drawings and algological names.”

Like the characters in Sanditon Margaret started a collection, which was nothing out of the ordinary. But she didn’t stop at merely building a collection she began to contact the famous marine biologists of the day , including Harvey whom was to become a family friend. It was the start of a programme of self-education about natural history generally and sea-life in particular. After 14 years of research and collecting she eventually she published her guide to British Sea-Weeds —in 1863 with a second edition in 1872. It included detailed coverage of 200 species.

To my surprise though the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography which has a short entry on Margaret gives her work on seaweeds just one line almost as an afterthought and instead concentrates entirely on the rest of her varied literary output: a novel or two, moral tales, a travelogue a couple of biographies, Aunt Judy’s Magazine and a range of books for children. There was also the very popular series of Parables from Nature, produced between 1855 and 1871, in which combined her faith with her love of natural history to teach moral and religious lessons. Her accomplishments are the more remarkable for having been achieved despite having ten children and being supportive of her husband’s parochial responsibilities. One way she did that was to make presentation books filled with mounted specimens of real seaweeds to sell to raise money for the poor of her husband’s parish.

By this point algology or the study of seaweeds had reached the same sort of popularity as Fern Fever or orchid mania. However, despite the fact the seashore was a place where social norms were less restrictive, and there was some licence to wear more practical dress the differences between the roles of women and men were still as noticeable. Margaret says, for example “If anything would excuse a woman for imitating the costume of a man, it would be what she suffers as a sea-weed collector from those necessary draperies. But to make the best of a bad matter, let woollen be in the ascendant as much as possible; and let the petticoats never come below the ankle.” However it’s also clear that the collecting part f algology could be viewed as a family activity. One of her diary entries for 1850 reads: ‘Set off for Filey, Alfred, self, seven children, two nurses and the cook. Arrived safely.,, went down to the sand and found seaweeds.’

Another vicar’s wife, Louisa Lane Clarke, published. The Common Seaweeds of the British Coast and Channel Islands; in 1865. Born in the Channel Islands like Gatty she had a wide literary output , publishing a novel in 1838 before turning to travel writing but after her husband died in 1864 she returning to Guernsey and spent the later years of her life writing local history, studying nature and writing several books on the use of microscopes and their application to seaweed. This included the 1858 work of reference, A Descriptive catalogue of the most instructive and beautiful objects for the microscope,

Another vicar’s wife, Louisa Lane Clarke, published. The Common Seaweeds of the British Coast and Channel Islands; in 1865. Born in the Channel Islands like Gatty she had a wide literary output , publishing a novel in 1838 before turning to travel writing but after her husband died in 1864 she returning to Guernsey and spent the later years of her life writing local history, studying nature and writing several books on the use of microscopes and their application to seaweed. This included the 1858 work of reference, A Descriptive catalogue of the most instructive and beautiful objects for the microscope,

None of these women attempted to become “professional” algologists or even seemed to claim their work was scientifically important, usually being content to defer to men’s expertise especially of it was Harvey. Margaret Gatty recalled how her family “often made Dr Harvey smile, by asking him to help a lame dog over a stile, when we wanted him to make a scientific statement intelligible to our unlearned ears.” Instead she merely hoped to impart ‘a little knowledge of the subject, in however desultory a way’. Nevertheless she felt an ‘intense source of gratification’ when Harvey named an Australian algae Gattya pinella and Dr Johnson xxx Her collection is largely preserved in the Charles Gatty XXXX at St Andrews University where it sits alongside some of Isabella Gifford’s.

Of course there were a whole host of other books on seaweeds published in the years after the appearance in 1843 of Anna Atkins’ book of cyanotypes. Amongst them Harvey’s A manual of the British marine Algae in 1849 , John Cocks, The sea-weed collector’s guide: 1853; William Johnstone and Alexander Croall , The nature-printed British sea-weeds : a history, accompanied by figures and dissections of the Algae of the British Isles in 4 volumes 1859-60; Shilry Hibberd’s The Seaweed Collector, and W H Grattan’s British marine algae : being a popular account of the seaweeds of Great Britain, their collection and preservation 1873.

But just as with Fern Fever there were serious ecological consequences of seaweed collecting. The impact had been noted by Charles Kingsley’s in his children’s book, The Water Babies ,where it was the water babies who responsible for mending broken seaweed and keeping rock pools neat and clean. Later , in 1907, Edmund Gosse, son of the marine life pioneer Philip, wrote of his father’s dismay at the devastation of the shoreline ecology by overzealous collectors. and his memories form a strident early critique of the seaside tourism coupled with the collecting habit especially on rock pools. It was as if “an army of ‘collectors’ has passed over them, and ravaged every corner of them. The fairy paradise has been violated, the exquisite product of centuries of natural selection has been crushed under the rough paw of well-meaning, idle-minded curiosity.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.