One of the highlights of my recent trip to southern India was to visit the botanic gardens in a place known now as Udhagamandalam, (officially at least) although I didn’t hear anyone anywhere call it that. Instead they all talked about Ooty.

One of the highlights of my recent trip to southern India was to visit the botanic gardens in a place known now as Udhagamandalam, (officially at least) although I didn’t hear anyone anywhere call it that. Instead they all talked about Ooty.

This is the popular abbreviation for Ootacamund, the “Queen of Hill Stations”, which sits about 7,500 feet up in the Nilgiri Hills. During the days of the British Raj it was where Europeans could go to escape the intense summer heat on the plains below. And of course, as elsewhere throughout the empire, wherever the British went, they constructed gardens including the one that I had read about and was keen to see…

As usual the photos are mine unless otherwise acknowledged

These days Ooty is probably more famous for the little narrow gauge mountain railway that you’ve probably seen on TV shows, which was constructed in 1908 and is one of the world’s few remaining steam railways.

These days Ooty is probably more famous for the little narrow gauge mountain railway that you’ve probably seen on TV shows, which was constructed in 1908 and is one of the world’s few remaining steam railways.

It takes nearly 5 hours to cover about 50 kilometres at what can only be described at a sedate pace, but it gave a great insight into the landscape of the Nilgiri Hills and was definitely a fun way to arrive…

Watch the video if you want to know more about it…..but I digress as I’m supposed to be writing about the botanic gardens!

I should start by saying that the botanic garden isn’t what it was in the days of the Raj. Of course there’s no reason why it should be – it has evolved as all gardens do. But despite the addition of many more locally inspired features such as statues or jokey elements designed to attract children, it still has more than a passing resemblance to a Victorian public park in Britain which is unsurprising since it was first established in 1845.

I should start by saying that the botanic garden isn’t what it was in the days of the Raj. Of course there’s no reason why it should be – it has evolved as all gardens do. But despite the addition of many more locally inspired features such as statues or jokey elements designed to attract children, it still has more than a passing resemblance to a Victorian public park in Britain which is unsurprising since it was first established in 1845.

Unfortunately there was very little information about its history, very little labelling, in places very little maintenance and it bore very little resemblance to a botanic garden as understood in the west.

Having said all that it was lots of fun and served as a starting point for me to do some detective work!

Let’s start with some background. It’s only after the Indian Mutiny of 1857 that India properly became part of the British empire. Before that British involvement was under the aegis of the East India Company who had gradually assumed political control of much of the country following the Seven Years War in the mid-18th century. By the first decades of the 19thc the Company was firmly established as the leading power in the subcontinent. Divided into three Presidencies or provinces, each with their own governor, it ruled some areas directly while in others the Indian princely rulers were left in control but largely under the “protection” of the company. After a series of wars with the rulers of Mysore which finished in 1799 some of the Nilghiri Hills were annexed by the Company and that’s when exploration, control and exploitation of these, until then remoter, parts really began.

Ooty’s potential was spotted as early as 1814 when two surveyors “ascended the hills …, penetrated into the remotest parts and made plans, and sent in reports of their discoveries.” Some time later two customs officers chased smugglers into the hills “and proceeded to reconnoitre the interior. They soon saw and felt enough to excite their own curiosity and that of others,” notably John Sullivan the Company’s local administrator. He went up into the hills himself, fell in love with the scenery and climate and in 1819 built himself a house, the first in what was to become Ooty. He had just returned from a long period of leave which he had spent at the Cape and its thought he bought back seeds, bulbs, and possibly even plants, from South Africa which were planted in the garden around it.

Sullivan recruited a trained gardener, a Mr Johnson to look after it, and by July 1821, it was reported his garden “had apple and peach trees — the latter already in bearing — as well as strawberries, and European vegetables”. Sullivan bought more land and built two other properties. He also acquired about 200 acres for agricultural and horticultural experiments, and well into the 20thc there was still evidence of fruit trees he planted.

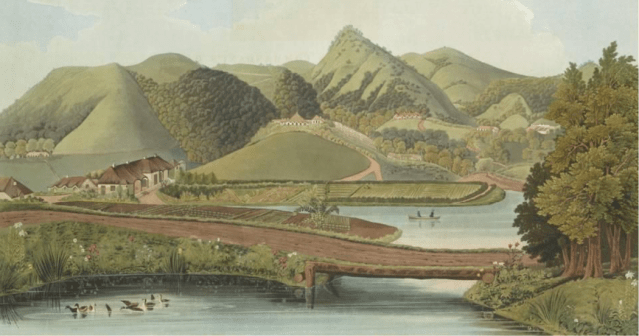

Ootacamund north of the lake from Observations on the Neilgherries by Robert Baikie, 1834

Amongst his many other endeavours was the damming of several streams to make a large lake just outside the settlement for irrigation. Described by an enthusiast as “like Como“ the explorer Richard Burton who visited in 1848 was scathing: it was actually “very muddy, and about as far from Windermere or Como as a London Colosseum or a Parisian Tivoli might be from its Italian prototype.”

Within a few more years the area had been visited and mapped, its climate assessed and recorded in detail, the indigenous people categorised, roads constructed, sanatoria established, missionaries sent, its flora and fauna catalogued, topographical features given British names and descriptive guides written. Other smaller settlements, notably Coonor were also being established with a days easy travel.

The mission school from Observations on the Neilgherries by Robert Baikie, 1834

One of those early guides, Observations on the Neilgherries published in 1834 by Dr Robert Baikie also discussed at length the economic potential of both local plants and imported ones. It was thought that coffee would grow on the lower slopes – which it does very well – and because Camellia Japonica was found, it was thought tea – Camellia sinensis -would also flourish – which indeed it does.

One of those early guides, Observations on the Neilgherries published in 1834 by Dr Robert Baikie also discussed at length the economic potential of both local plants and imported ones. It was thought that coffee would grow on the lower slopes – which it does very well – and because Camellia Japonica was found, it was thought tea – Camellia sinensis -would also flourish – which indeed it does.

Baikie commented that “My friend the late Dr. Christie had come to the same conclusion, and commissioned some plants from China, some of which came into my possession after his death, and have been distributed to various parts of the hills for trial.” [I was under the impression that the first tea plants from China didn’t arrived from Canton until 1834 and then only in seed form, so if anyone knows more about Dr Christie and his acquisition of tea plants I’d love to hear more]

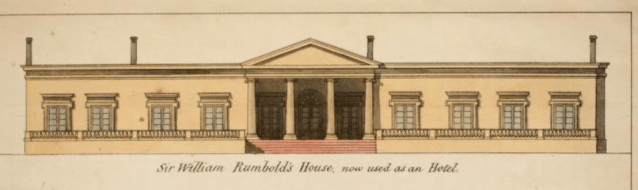

Rumbold’s House from Observations on the Neilgherries by Robert Baikie, 1834

Baikie also gives a sense of the speed and scale of the development. By the time he was writing there were “upwards of 70 habitable houses in Ootacamund, of every size and description, from the palace built by Sir W. Rumbold down to thatched cottages with two or three rooms. Of these, 25 or 28 (besides Sir W. Rumbold’s large house, now converted into an hotel) are in point of size and accommodation fitted for the reception of large families; the others are smaller, and better fitted for bachelors or small families. During the last year there were between 120 and 140 people …resident at Ootacamund, of which from 40 to 45 were married people, with families. A very elegant church in the Saxo-Gothic style is one of the greatest ornaments of the place.”

Baikie also gives a sense of the speed and scale of the development. By the time he was writing there were “upwards of 70 habitable houses in Ootacamund, of every size and description, from the palace built by Sir W. Rumbold down to thatched cottages with two or three rooms. Of these, 25 or 28 (besides Sir W. Rumbold’s large house, now converted into an hotel) are in point of size and accommodation fitted for the reception of large families; the others are smaller, and better fitted for bachelors or small families. During the last year there were between 120 and 140 people …resident at Ootacamund, of which from 40 to 45 were married people, with families. A very elegant church in the Saxo-Gothic style is one of the greatest ornaments of the place.”

St Stephen’s Church from Observations on the Neilgherries by Robert Baikie, 1834

One of the main reasons for this, is that despite being between 330 and 385 miles from Madras, depending on the route taken, there were early visits by two governors of the Madras Presidency. One of them Stephen Lushington stayed in 1829 and ordered road improvements but also drew up plans for major horticultural and agricultural improvement projects. There were already at least two European gardeners working in and around Ooty probably for the Company and Lushington ordered a large stock of tools, including four ploughs, and six horses to work them. He also asked the Company to send out a large quantity of agricultural and garden seeds, as well as fruit trees, and to recruit farmers and mechanics from Britain to come and settle. The Company was not convinced and refused almost all his requests, so that the projects never got going.

By the late 1830s the then governor, Lord Elphinstone, who intensely disliked the climate in Madras effectively made Ooty the seat of summer government, although that wasn’t made official until 1870. The government even rented two houses for officials with the gardens maintained by “a comparatively large staff for this purpose” although “they appear however to have been more of an ornamental than useful character, and the general public derived no benefit from them.”

Near Ootacamund, George Bellassis January 1852

Image courtesy of the British Library | All Rights Reserved

Of course the residents, both permanent and the increasing number of seasonal visitors needed feeding and Baikie explained how gardeners “have succeeded perfectly with almost every description of esculent vegetable to be found in Europe. The list extends to potatoes in great quantity and first-rate quality; cabbage, cauliflower, savoys, French beans, epinage, peas, lettuces, beet-root, radishes, celery, turnips, carrots, &c. &c Sea-kale, asparagus, and tomatas are more rare, but nevertheless thrive very well….I have seen very tolerable plums, peaches, nectarines, apples, citrons, and loquats. Oranges and limes grow wild in great abundance at Orange Valley, and doubtless would be improved by cultivation.” He goes on to extol the virtues of the bazaar [even adding a price list], as well as the Parsee-run shops where “everything in the way of liquors, Europe supplies, cheese, pickles, preserves, &c. &c. are to be found, good, and at reasonable prices.”

After a short-lived attempt to run a communal market garden which would supply the growing number of European residents with fruit and vegetables for a monthly subscription of 3 rupees, in 1847 a plan suggested setting up a Horticultural Society, and creating a public garden. It received the enthusiastic backing of the then governor of the Madras presidency, the Marquis of Tweeddale.

After a short-lived attempt to run a communal market garden which would supply the growing number of European residents with fruit and vegetables for a monthly subscription of 3 rupees, in 1847 a plan suggested setting up a Horticultural Society, and creating a public garden. It received the enthusiastic backing of the then governor of the Madras presidency, the Marquis of Tweeddale.

An agricultural improver on his own estates in Scotland Tweeddale made enquiries for an experienced gardener from Britain who would be paid out of public funds to oversee the project. Its clear from his request to the East India Company’s board that there had already been quite a lot of imported plants: Trees and shrubs from New South Wales were growing “in luxuriance,” while English oaks and Scotch firs were also doing well. There were also the extensive collections of European flowers to be found in many domestic gardens.

Back in Britain the royal gardens at Kew had just been taken over by the government for use as a National Botanic Garden under the directorship of William Jackson Hooker. One of Hooker’s ambitions was to create a chain of botanic gardens round the growing British empire to act as bases for testing the economic potential of crops from other parts of the empire. In response to Tweeddale’s request it was one of Kew’s gardeners, William McIvor, originally from Dollar in Clackmannanshire, who was chosen to go out to Ooty and take charge.

A site of 51 acres [21 hectares] of rough jungle g was chosen and a small committee was set up who issued a prospectus. This explained that “The want of agreeable rides, walks, and drives, in the valley of Ootacamund is a constant subject of complaint by those who are resident in the place”. There was also an “almost total absence of fine flowers, for the growth of which the climate is so admirably adapted” and interestingly that “for the want of a depot for their collection, horticulturists at home have as yet but few of the beautiful flowers indigenous to the Neilgherries, and in the jungles that surround them.”

They called for seeking donations and subscriptions and Tweeddale headed the list with a gift of 1000 rupees. The EIC itself offered 100 rupees to help running costs, supplied the necessary tools for free and set up a “The Committee of the Ootacamund Horticultural Gardens” to manage the new gardens.

When he arrived in 1848 McIvor found “the upper portion” of the proposed site “was a forest, with heavy trees on its steep and rugged banks, the lower part was a swamp, the whole being traversed by deep ravines. To fill up these an immense quantity of earth was required.” This must have been quite daunting especially since there was not enough cash to employ the labour to do the work. He must have been quite resourceful tho because instead “advantage was taken of the rainy season to force the soil by flushes of water into these ravines from cuttings and levellings, the earth thus carried with the water being deposited in the places required, behind screens of wicker work, formed of brushwood and rubbish, and thus was accomplished at a trifling cost, and in a most efficient manner a work, which if executed in the usual way, would have exhausted the resources of the institution.” He also reported that “The steep and rugged banks have also been transformed into easy walks, terraces, lawns and flower beds arc now planted with a choice and rare selection of plants, illustrating the vegetable productions of a large portion of the world” while a bandstand was added in 1864.

When he arrived in 1848 McIvor found “the upper portion” of the proposed site “was a forest, with heavy trees on its steep and rugged banks, the lower part was a swamp, the whole being traversed by deep ravines. To fill up these an immense quantity of earth was required.” This must have been quite daunting especially since there was not enough cash to employ the labour to do the work. He must have been quite resourceful tho because instead “advantage was taken of the rainy season to force the soil by flushes of water into these ravines from cuttings and levellings, the earth thus carried with the water being deposited in the places required, behind screens of wicker work, formed of brushwood and rubbish, and thus was accomplished at a trifling cost, and in a most efficient manner a work, which if executed in the usual way, would have exhausted the resources of the institution.” He also reported that “The steep and rugged banks have also been transformed into easy walks, terraces, lawns and flower beds arc now planted with a choice and rare selection of plants, illustrating the vegetable productions of a large portion of the world” while a bandstand was added in 1864.

The garden was enlarged three years later by the purchase of what is now the more level entrance area.

An early outside visitor was the explorer Richard Burton who was not a fan of Ooty. He said there were public gardens which had the usual “scandal point,” where you meet the ladies and exchange the latest news but otherwise “The sum of about 200l., besides monthly subscriptions, was expended upon the side of a hill …, now bearing evidences of the fostering hand of the gardener in the shape of many cabbages and a few cauliflowers.”

The McIvor conservatory, now closed and sadly in need of repair

McIvor must have set up a small greenhouse because in 1855 the Governor-General, who remarked that the glass house which then existed for the purpose of raising young plants was “little larger or better than a cucumber frame” and money was found for the construction of a proper conservatory in 1856. This was soon described as “a melancholy and unsuitable structure,” and eventually in 1887 it was pulled down, and the material salvaged to help build the present structure. A much larger modern glasshouse now houses mass displays of colourful but common plants.

A cascade which has seen better days

McIvor also initiated the exchange of plant material with other botanic gardens in India, as well as those in Melbourne and Mauritius, introducing ‘various useful trees, shrubs, herbs etc from other countries similarly situated’. He also introduced several sorts of European fish including carp, tench and trout into the garden and lake.

Despite his undoubted skills he may not have been the easiest man to work with, and there were several reports of run-ins with his management committee. However these were resolved in his favour and in the end the committee was disbanded and when the East India Company was itself replaced by the British government in 1857 the gardens became part of the Indian Forestry Department.

Records from this time improve so that we know a fernery and orchid house were built in 1864 while ornamental ponds and cascades were added around the same time,although several of them are now in dire need of repair.

Records from this time improve so that we know a fernery and orchid house were built in 1864 while ornamental ponds and cascades were added around the same time,although several of them are now in dire need of repair.

McIvor retired in 1871 but had already planned seed houses and a herbarium, which followed in 1872, and in the same year rather grand iron entry gates were installed. He remained in Ooty until his death in 1876.

The end of the cascade where the water would have flowed into one of the many ponds. Now, as you can see inhabited by a few crocs

Although the Government Gardens were, and in many ways still are an impressive achievement they are not McIvor’s great success or claim to fame and I’ll cover that in another post in a few weeks time.

McIvor’s legacy also includes a large number of mature trees especially on the upper slopes, several of which came down in a recent storm, but unfortunately there’s little evidence of much tree planting over recent decades. Elsewhere there are other recognisable features from its colonial past although, they have not always been used or maintained in the same style as they would have been. I suspect this is simply for financial reasons.

The last major “improvement” was the construction of the “Italian Garden” built by Italian prisoners of War who were sent to India from Europe between 1914 and 1918.

The last major “improvement” was the construction of the “Italian Garden” built by Italian prisoners of War who were sent to India from Europe between 1914 and 1918.

The Italian Garden with the creeper covered bandstand

Nowadays Government Gardens are a bustling and extremely popualr palce for the local population. There is an annual flower show, which last year atracted well over 150,000 visitors. And while they might not resemble a western botanic garden they still house over 2000 species of plants and trees from all over the world… and as we will see in another post soon they are not the only garden worth going to see in this part of the world.

Nowadays Government Gardens are a bustling and extremely popualr palce for the local population. There is an annual flower show, which last year atracted well over 150,000 visitors. And while they might not resemble a western botanic garden they still house over 2000 species of plants and trees from all over the world… and as we will see in another post soon they are not the only garden worth going to see in this part of the world.

The sunken garden is one feature being restored and repainted.

For further information good places to start are: the first history of the town. Frederick Price, Ootacamund: A History. 1906 which includes a chapetr on the origians of the gardens. There are also lengthy official reports on the gardens which were too deatiled to include here but that for 1857 can be found in

For further information good places to start are: the first history of the town. Frederick Price, Ootacamund: A History. 1906 which includes a chapetr on the origians of the gardens. There are also lengthy official reports on the gardens which were too deatiled to include here but that for 1857 can be found in

You must be logged in to post a comment.