© The Tabley House Collection Trust

There can’t be many great landscape gardeners who, as a young man, fought against Napoleon in the Peninsular War or against the Americans in the War of 1812. Yet one who did both went on to become a well-known artist and then one of the leading garden designers of the 19thc, with over 250 sites including some of the most important in the country under his belt by the time he died in 1881.

He was William Andrews Nesfield usually mainly remembered for his complicated colourful geometric parterres but who was actually a far more nuanced and sophisticated designer than he is often given credit for.

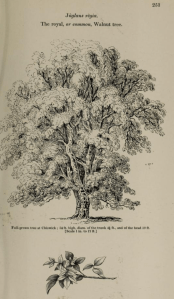

Mamhead Park by Nesfield , from the Nesfield Archive in Australia scanned from Country Life 8th April 1993

Believe it or not this post was largely written long before news broke of the Garden Museum’s acquisition of the Nesfield archive from his descendants in Australia! For more information about that see the Museum’s announcement.

Nesfield has not always had a good reputation. William Robinson said of him in his obituary in The Garden: “He approached landscape gardening from the artificial side” and believed that ” the geometry of a past age should form the foreground of what might be the fairest scenes in our garden land .,., rather than Nature in her wealth, simplicity, and dignity.” This kind of gardening was, Robinson concluded, “utterly unsatisfactory”. Even unkinder was Edward Hyam’s opinion: ‘The detail of Nesfield’s work was, in short, repulsive and he was one of those responsible for that disagreeable kind of gardening known as bedding out.” [Edward Hyams. The English Garden,p. 122.].

Nesfield has not always had a good reputation. William Robinson said of him in his obituary in The Garden: “He approached landscape gardening from the artificial side” and believed that ” the geometry of a past age should form the foreground of what might be the fairest scenes in our garden land .,., rather than Nature in her wealth, simplicity, and dignity.” This kind of gardening was, Robinson concluded, “utterly unsatisfactory”. Even unkinder was Edward Hyam’s opinion: ‘The detail of Nesfield’s work was, in short, repulsive and he was one of those responsible for that disagreeable kind of gardening known as bedding out.” [Edward Hyams. The English Garden,p. 122.].

Pretty damning stuff so let’s see what you think after you’ve heard more about him!

William Andrews Nesfield, born in Chester-le-Street, Co. Durham, England in 1794. His father was a well-connected clergyman and he was schooled at Winchester which he disliked, and then Trinity College, Cambridge. Expected to follow in his father’s footsteps and take holy orders, William decided instead to join the Royal Military Academy, in Woolwich, in 1809. There he was taught to draw and survey by Thomas Paul Sandby, the son of the water-colourist Paul Sandby.

Family connections gained him a commission and in 1813 he was involved in the tail end of the Peninsular War, before those same family connections saw him appointed as aide-de-camp to Sir Gordon Drummond, commander of the British forces in Canada during the War of 1812 against the United States. But in 1818 he changed tack again, resigned from the army and took up watercolour painting.

Chatsworth by Nesfield undated image from Watercolour World and copyright the Trustees of the Chatsworth Settlement

Waterfall near Ludlow, by Nesfield, undated

© The Trustees of the British Museum

It sounds a bizarre switch but he obviously had talent, and took lessons from Copley Fielding before embarking on painting trips round Britain and Europe with colleagues including David Cox, John Varley and Edwin Landseer. He earned the praise of John Ruskin in Modern Painters [1843] for his depictions of water, “being a man of extraordinary feeling, both for the colour and the spirituality of a great waterfall ; exquisitely delicate in his management of the changeful veil of spray or mist ; just in his curves and contours ; and unequalled in colour, except by Turner.”

Meanwhile his father had remarried. His second wife was Marianne, aunt of Anthony Salvin, who was to become an architect and Nesfield’s friend and sometime business partner. Salvin was to marry Nesfield’s sister in 1826 and the three shared a house most of the time until 1833 when Nesfield married Emma Mills, granddaughter of the Archbishop of York.

That year Salvin now with a family to support, took a long lease on a house in East Finchley with a large garden and ten acres of paddocks. It was convenient for travelling into London and had extensive views. He began buying more land locally and with Nesfield bought adjoining plots in nearby Fortis Green, then still a remarkably rural outpost on the northern edge of London..

Shortly afterwards Salvin designed a pair of [unusally for him] Italiante villas there. But these were not the small suburban dwellings you might iamgine from the name: they were enormous, each having a garden stretching to over 4 acres! Nesfield and his wife m0ved into one in 1836 and he designed the grounds to take advanatge of the extensive views overs tiwards Highgate Church, Hampstead Heath and Kenwood. As you can see the rear garden was small but included a simple small parterre – that led the eye over the field below which was also Nesfield’s – and where he kept a flock of sheep – to the landscape beyond. It was a clear foretatse of things to come.

Shortly afterwards Salvin designed a pair of [unusally for him] Italiante villas there. But these were not the small suburban dwellings you might iamgine from the name: they were enormous, each having a garden stretching to over 4 acres! Nesfield and his wife m0ved into one in 1836 and he designed the grounds to take advanatge of the extensive views overs tiwards Highgate Church, Hampstead Heath and Kenwood. As you can see the rear garden was small but included a simple small parterre – that led the eye over the field below which was also Nesfield’s – and where he kept a flock of sheep – to the landscape beyond. It was a clear foretatse of things to come.

At some time around 1830 time Nesfield had met John Claudius Loudon and over the next few years contributed not only some illustrations to the Gardener’s Magazine and Arboretum et Fruticetum Britannicum, but also a series of articles for the magazine. These covered a range of subjects from “An improved Mode of painting, lettering, and varnishing Tallies” ie the best way to preserve labels on -plants, to another short piece on jam-making. as well as accounts of garden visits he has made including one to Allanton, the seat of Sir Henry Steuart the inventor of a tree transplanting machine that I’ve written about before .

They obviously became friends and there are several positive references to Nesfield and his work. In 1836, for example, Loudon reports that “In the grounds of different noblemen’s and gentlemen’s residences throughout the country, many alterations are going forward under the direction of Mr. Nesfield, a landscape gardener who only requires to cultivate a botanical and horticultural knowledge of trees and shrubs to place him at the head of his profession. Mr. Nesfield perfectly understands the difference between the picturesque and the gardenesque; between facsimile imitation of nature, and imitation on artistical principles; and between lowering and caricaturing real scenery, and elevating and ennobling it.”

“It is a happy circumstance when the architect and the landscape-gardener operate harmoniously together; and this has been, and is long likely to continue to be, the case with Mr. Nesfield, and his brother-in-law, Anthony Salvin, Esq.”

Loudon also made the trip out to Fortis Green one day to see the garden and ended up writing a lengthy article about it in The Gardeners’ Magazine in February, 1840, The information was repeated almost word for word in Loudon’s The Villa Gardener of 1850, except that by then Nesfield had moved.

Loudon was particularly impressed by Nesfield’s sheep. They made him a profit – a course of action that appealed very much to Loudon’s sense of agricultural economy, and he outlined Nesfield’s system and accounts which resulted in an annual profit of £18 15s 10d as well being “very ornamental”!

Unfortunately painting doesn’t always pay and Nesfield, now with a wife and baby son, was always short of money so in order to make ends meet Salvin looked for surveying and garden design work for him. This led to a gradual shift away from painting and the slow development of a new career as a landscape gardener. It worked and Loudon wrote that “Mr Nesfield has long been well known as a landscape painter of eminence, and as connected with the society of painters in watercolours. He has lately directed his attention to landscape gardening, and that with so much success that his opinion is now sort by gentleman of taste in every part of the country.”

Just as Salvin began to specialise in designing Elizabethan-Jacobean revival style buildings and always sought historical accuracy for his work, by collecting images and accounts of historic building, Nesfield too became interested in the past and collected plans and engravings of historic gardens.

Design for the gardens of the Tuileries by Boyceau

His biographer Shirley Evans found a Book of Patterns in his archive now in the Garden Museum but until recently in Australia [unfortunately not catalogues or digitised] which contained a large number of prints and designs from what he termed the ‘Old Masters in Gardening’. These were mainly from 17thc France and included Boyceau and Le Notre who specialised in the parterre-de-broderie or the embroidery parterre. Nesfield would refer to this for his work not only with his brother-in-law Salvin but with his other architects with whom he collaborated including the two other major Elizabethan and Jacobean revival architects, William Burn and Edward Blore. He didn’t copy their designs but took elements and reworked them and his regular use of the parterre-de-broderie is usually seen as his trademark.

However, Evans work in his archive shows that the parterre was only part of his stock in trade. As we saw in his own garden at Fortis Green He was also interesting the setting of the house and linking it o the wider landscape beyond. She summarises his primary purpose as wanting “to achieve a unity between these two areas, which he did by employing the concepts of variety, simplicity, breadth and proportion and instigating a boundary line which usually consisted of low balustrades, between the artificial and the naturalistic. The area around the house, in order to complement this man-made structure, was artificially conceived whilst the area beyond was naturalistic.”

These principles are further evidenced in his Reports to Patrons, which like Repton’s Red Books summed up his design ideas in a handwritten proposal of each client. A number of them survive in his archive and can be found in an appendix to Shirley Evan’s Ph.D thesis. They show how he regarded landscape design as ‘the Art of painting with Nature’s materials‘

Salvin was about five year older than Nesfield and so its not surprising that his career took off earlier. His first major commission was at Mamhead in Devon for a vast Elizabethan style mansion for Robert Newman, the MP for nearby Exeter. This was begun around 1828 and Salvin is said to have designed the garden ornaments, pools, fountains and urns. It’s tempting to think that Nesfield might have offered help, especially as we know visited Mamhead because Shirley Evans found a painting he had done of the house.

Certainly Salvin enabled Nesfield to get a foot on the career ladder by introducing him to his own patrons. This began in earnest in 1834. The first instance was at North Runcton Hall a Tudor house in Norfolk, where Salvin was adding a large extension. Although its thought William Sawrey Gilpin, the doyen of gardeners designers of the day, designed most of the grounds Nesfield got the job of creating a simple parterre and in his Report to the client he tells him “The decoration of this parterre ought to partake of a totally different character from that of the flower garden, & it is proposed, instead of dug beds, to introduce grass plots cut into scrolls with various vases & green house plants set according to plan” [Gurney MSS. cited by Shirley Evans]. Unfortunately we have no idea what this looked like because, like virtually all of his early work there is no surviving evidence, not even paintings or sketches, apart from the archive. The house was demolished in the 1960s.

I’ve also been surprised by how little his work is mentioned in the contemporary gardening press. Even houses which are described in some detail rarely the fact that the gardens have been redesigned and his name is rarely mentioned. I suspect that’s often the case with garden designers compared with architects, or even head gardeners.To make matters worse As we’ll see his gardens, especially the parterres, were complex and expensive to maintain and have usually been swept away or at the very lest drastically simplified .

I’ve also been surprised by how little his work is mentioned in the contemporary gardening press. Even houses which are described in some detail rarely the fact that the gardens have been redesigned and his name is rarely mentioned. I suspect that’s often the case with garden designers compared with architects, or even head gardeners.To make matters worse As we’ll see his gardens, especially the parterres, were complex and expensive to maintain and have usually been swept away or at the very lest drastically simplified .

1834 also saw William Sawrey Gilpin [see earlier post for more information about him] start his last commission at Scotney Castle in Kent. Salvin was building a huge new Elizabethan style heap on top of the hill overlooking the existing mediaeval castle and its 18thc extension on the island below, before turning them into a romantic eye-catcher ruin for Edward Hussey. Nesfield put forward proposals for formal parterres around the new mansion but these were rejected in favour of Gilpin’s much looser design.

Undaunted it wasn’t long before other clients arrived. Salvin was becoming busier and busier. He was working on remodelling and extending 15thc Methley Hall for the Earl of Mexborough between 1830 and 1836. He introduced Nesfield to the earl and they clearly got on well and he was introduced to the earl’s friends with, almost inevitably, work cropping up. The hall was demolished in the late 1950s.

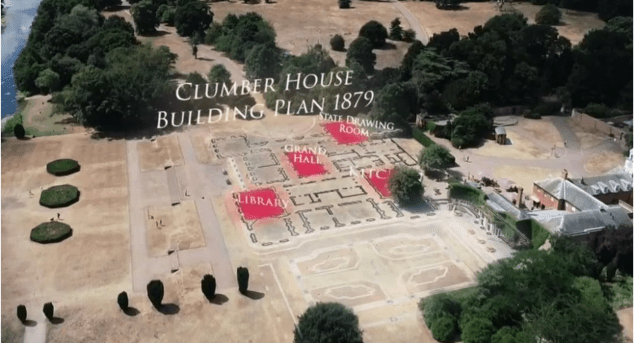

Clumber Park in 1923

By 1837 the owner of Clumber, the Duke of Newcastle records in his diary that he spent the day with Nesfield presumably discussing possibility including an arboretum to link the pleasure gardens to the wider landscape and lake. His idea for the entrance was to emulate Repton’s work at Ashridge’s Rosary some 25 years earlier, and use a large wire trelliswork arch . At the lakeside he suggested a rustic building fronting a garden largely of plants from the genus Rosa. As a way of persuading the duke of his ideas he wrote telling him that ‘At the same time I was drawing the plans for Arboretum & French garden, Mr. Loudon happened to call – and I showed him the designs which he highly approved of- the latter was especially admired in as much as he begged for a tracing of it for his publication”. Later there were schemes for a cascade and there’s also a plan from 1851 for The Battery, a rampart jutting into the lake built which once was home to 26 bronze model cannons and several working ones for the Mock sea battles that were held on the lake.

By the early 1840s Nesfield’s career really began to take off. I’ve found about 50 properties that he worked on or drew plans for during the 1840s alone . They range from Kew, Buckingham Palace and Alton Towers to Holkham, Alnwick and Trentham. Most, however are lesser know and his work is largely unrecorded as many of them have long been demolished , while most of the rest have institutional use. I’ve tried to check through as many of these sites as I can but there is usually very little visual evidence, and until Shirley Evans carried out her research very little documentary evidence available publicly either.

Merevale in Warwickshire is an exception and still remains a private residence. Between 1838 and 1844 the house was rebuilt to designs by Edward Blore and Henry Clutton. Nesfied designed formal terraced gardens, with wide, stone-flagged steps and a geometric, stone-kerbed parterre (all listed grade II). You get a much better idea of the scale of his work from a short drone video on Youtube.

Because much of his work has been lost and there is very little visual or documentary evidence for it its been quite difficult to research many of the sites but I’m still looking and I’m sure the Garden Museum will do better than me, so I’ll follow this up with another post in due course

For more information: best places to start are Shirley Evans Ph.D thesis which is available via the University of Plymouth’s website, and Masters of Their Craft her biography of Nesfield and his two sons who followed in their father’s footsteps as landscape architects and designers.

You must be logged in to post a comment.