The Maharaja

When was the last time you needed a passport to visit a garden? Or indeed had to walk past heavily armed police to go in? We ran into that problem on my recent visit to south India, although luckily the passports weren’t locked in the safe in our hotel as recommended but in the car, or we’d have been refused admittance.

The garden we were visiting was Brindavan, a huge formal garden on the outskirts of Mysore, that was laid out between 1924 and 1932. Like us, you might be wondering why we needed passports , but perhaps a look at some of the long distance views of the garden later in this post will give you a clue.

Mysore is, unlike all the other Indian cities I’ve visited, amazingly green. It has tree-lined streets, broad avenues with wide shrub filled verges and several gardens in the city centre. Like Brindavan much of this is due to the foresight of a reforming maharaja and his chief ministers, and the trust they placed in a Kew-trained German-born gardener and planner I’d never heard of but who, I’ve since discovered, is probably the most influential European gardener ever to work in India.

As usual the images are my own unless otherwise acknowledged

The Maharaja

Mysore was once a large and wealthy state occupying a sizeable chunk of southern India until much of its territory was taken over by the East India Company in 1799 following the Anglo-Mysore wars. In 1831, the British took direct control of the rest of the princely state, side-lining the Indian rulers and leaving them as figureheads.

Two years of intense drought in 1876 and 1877 led to a terrible famine which was made worse because the colonial government continued to export large quantities of Indian-grown grain to the UK, instead of retaining it to feed the population. As a result its thought that as many as a million people, getting on for 20% of the state’s population died. The maladministration of the disaster helped lead to the reinstatement of the former royal family, with just a British resident “advisor”.

In 1895 an 11 year old boy succeeded to the throne as Maharaja Krishnaraja IV, assuming full power when he became 18 in 1902. He was to become a great ruler, developing agriculture and the economy, improving public health, supporting public education particularly for girls, founding a university, generally supporting arts and culture, and in the process transforming Mysore into a modern state. He is still revered in the city as what Gandhi called a “saintly king”.

The dam towering over the gardens

Given droughts and water shortages were a consistent feature of life one of his most important projects was to improve the supply of water for irrigation. It was an extremely expensive undertaking but against strong opposition he approved the construction of a massive dam across the Kaveri river a few miles away from Mysore city. The foundation stone was eventually laid in 1911 and since 10,000 people worked on the construction it helped alleviate local unemployment too. The project was finally completed in 1924 and named Krishnaraja Sagar Dam after him. The dam is 8600 feet in length and 130 feet in height. The water retained covers over 50 square miles and is, I think, the largest man-made lake in India. Since the reservoir supplies much of the drinking water for the whole state, as well as hundreds of square miles of farmland, there have been security concerns which apparently explains the need for foreigners to show passports, and access to anywhere near the dam wall is prohibited.

Krumbiegel’s carte de visite

from Garden History, Vol. 40, No. 2 (2012)

When the dam wall was completed it left a huge area of more than 60 acres in its immediate shadow. The Maharaja and his chief minister or Diwan, Sir Mirza Ismail, decided to fill it with an ornate public garden and commissioned Gustav Hermann Krumbiegel to design it.

Who? I can hear some of you saying and well you might, because now since his death in 1956 he has been almost forgotten even in India. Krumbiegel was born in 1865 near Dresden and after working in Germany as a horticulturist moved to England in 1888 to train and work at Kew. One of his tutors was William Goldring who was soon to be recruited by the Maharaja of Baroda to create gardens in the around his new Lakshmi Vilas Palace, then the biggest palace in the world. [For more on Goldring and his work at the palace see this earlier post].

When Goldring decided to return to Britain, the Maharaja of Baroda came to England himself to recruit a replacement from Kew. Apparently after interviewing seven or eight candidates he offered the post of superintendent of the state’s gardens to Krumbiegel, who was then aged only 28.

It was soon obvious that Krumbeigel was more than a good gardener. He was also an agricultural improver, architect, urban planner and ecologist. These talents came into play not only in Baroda but when he was allowed to work for other princely rulers. In particular he worked for the Maharaja of Mysore probably because the two royal families knew each other well and had adjoining summer palaces at Ooty. Eventually in 1907 he was asked to take over the Lal Bagh, in Bangalore. [A Bagh is Hindustani for garden while Lal has two meanings, beloved and red] [I’d planned to visit Lal Bagh myself. right at the end of my trip but thanks to Air India cancelling flights I didn’t get to see them!]

[Krumbeigel was to remain in India for the rest of his life and his story is fascinating and only just being rediscovered so with any luck there’ll be another blog post soon]

In most of the gardens he worked on Krumbiegel was building on the work of earlier designers and horticulturists but at Brindavan he was able to start with a blank canvas and work on a grand scale. It was to be an interesting project because his training was in European design and it was European styles that were usually employed at the various palaces he had worked on. While he quickly appreciated and used the indigenous flora he hadn’t really needed to adapt to Indian garden design. Yet he responded enthusiastically to suggestions from Sir Mirza Ismail that they look for inspiration to the great Mughal gardens of the past.

Two in particular were influential. The first was the famous Shalimar Gardens in Srinagar, the capital of Kashmir which had been laid out for the Mughal emperor Jahangir in 1619. The other was closer to home at Lal Bagh in Bangalore. The state of Mysore was traditionally Hindu but in the mid-18thc the ruling family had been toppled by Muslim invaders led by Hyder Ali. In 1760 Ali began the layout of Lal Bagh basing it on another, now lost, Mughal garden at Sira about 120km north of Bangalore. The work was then finished by his son Tipu Sultan before he was overthrown by the East India company in the Anglo-Mysore wars.

The site of Brindavan is unusual. Not only does it run alongside and butt up against the dam wall but the formal parts are also fairly restricted in width. The masterplan divides it into two main garden sections, north and south which are separated by a huge boating lake. The areas to the east [ie below them on the aerial shot] are woodlands on the left, car parking and spillway in the centre and trial orchards and experimental horticultural farmland on the right.

The day we visited it the gardens were almost deserted, with only a few dozen people on the entire site, but as you can see from the entrance with its rails to control the queues, and from the car parking space visible in the aerial shot, the gardens attract tens of thousands of people on festival days – probably totalling over a quarter of a million visitors a year.

Let’s take a quick tour round starting in the southern section. The visitor enters by a path that leads across the flat central area and ends at the towering dam wall. A pergola made of massive stone columns and covered in creepers and climbings plants of several sorts runs along both sides of the garden. Unfortunately some parts have fallen down while it looks as if there were plans to extend this but which were never implemented.

They lead up through three shallow terraces to the steep curved slopes at the far southern end which are planted with broad stripes of foliage plants. On top of the slope is a viewing platform and a posh hotel.

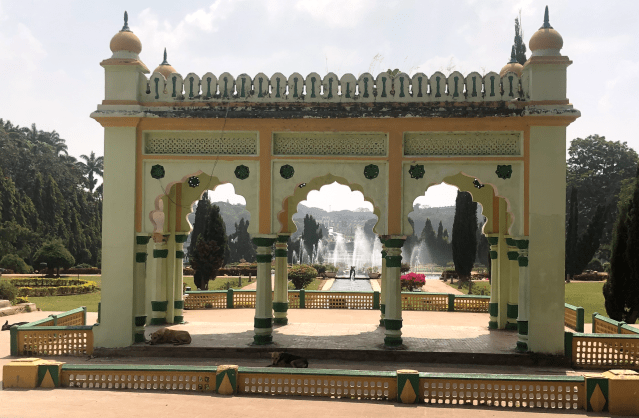

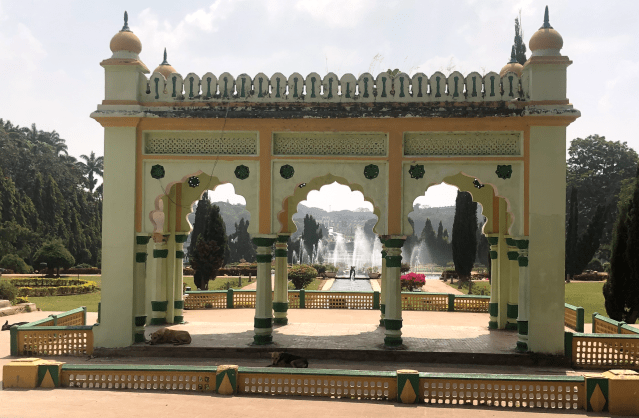

From the top you can look down on the whole layout which is strictly geometric, with everything in straight lines and not a curve in sight. Three terraces lead down the garden each containing a Mughal-style water garden with cross canals, shallow cascades and fountains which are surrounded by separate large grass areas and some low ornamental planting.

Several Mughal-style pavilions stand at the sides, most now in a poor state of repair. In one of these is a plaque commemorating Sir Mirza Ishmail the chief minister who was the driving force behind getting the gardens built, which quotes Dorothy Gurney’s 1913 poem God’s Garden

Several Mughal-style pavilions stand at the sides, most now in a poor state of repair. In one of these is a plaque commemorating Sir Mirza Ishmail the chief minister who was the driving force behind getting the gardens built, which quotes Dorothy Gurney’s 1913 poem God’s Garden

The steps up to the roadway along the dam wall are now blocked

Stepped access from the gardens leads to the roadway that runs along the complete length of the dam. Unfortunately this has been closed off for security reasons which is a great pity because the views across the reservoir behind the dam must be spectacular.

Between the north and south sections lies an enormous lake, designed originally for boating. As you can see it has seen better days. It is bounded on one side by the high dam wall and on the other by a smaller dam wall that acts as the pathway between the two halves of the garden, and overlooks the slipway to the river and the fields below.

Crossing the lake to the northern side leads to a similar, but much smaller and narrower terraced arrangement with canals and other water features. These lead up to another large Mughal style pavilion.

Sir Mirza left a short rather poetical account in his memoir : “Brindavan, seen by day, is a fascinating garden. It is approached by an excellent motor road leading to a pavilion. There the visitor sees the terrain fall away in a series of terraces to the river-bed and rise again similarly on the other side. Each terrace is divided across by a wide strip of water in which fountains continuously play. Vertically, from topmost pavilion to river-bed, yet another strip of water begins with a miniature waterfall, and there is a ‘race’ from one terrace to the next. Flower-beds and trim box edges border lush lawns. The whole terrain on each flank is fringed by a sweep of tall trees.

Sir Mirza left a short rather poetical account in his memoir : “Brindavan, seen by day, is a fascinating garden. It is approached by an excellent motor road leading to a pavilion. There the visitor sees the terrain fall away in a series of terraces to the river-bed and rise again similarly on the other side. Each terrace is divided across by a wide strip of water in which fountains continuously play. Vertically, from topmost pavilion to river-bed, yet another strip of water begins with a miniature waterfall, and there is a ‘race’ from one terrace to the next. Flower-beds and trim box edges border lush lawns. The whole terrain on each flank is fringed by a sweep of tall trees.

“From dawn to dusk every nuance of Nature’s light and shade is caught up and reflected in the unfolding waters which stretch below. When darkness comes, as by some touch of a magic wand, they begin to spray newels of liquid light, each fountain being given an individuality all its own. So the enchanted eye is led onward, downward, to the river’s edge, softly aglow with half-concealed and half-revealed light. And there in the river’s centre, rising a sheer 150 feet, is a tower of water which the wind claims for its own sport, whirling its drift in strangely * attractive designs. On the far bank glowing fountains lead up to a flood-lit arch which has the effective outer darkness for foil.”

“From dawn to dusk every nuance of Nature’s light and shade is caught up and reflected in the unfolding waters which stretch below. When darkness comes, as by some touch of a magic wand, they begin to spray newels of liquid light, each fountain being given an individuality all its own. So the enchanted eye is led onward, downward, to the river’s edge, softly aglow with half-concealed and half-revealed light. And there in the river’s centre, rising a sheer 150 feet, is a tower of water which the wind claims for its own sport, whirling its drift in strangely * attractive designs. On the far bank glowing fountains lead up to a flood-lit arch which has the effective outer darkness for foil.”

Brindavan has always been well-known locally but became much more of a tourist attraction in the late 1960s when it was discovered by Bollywood and particularly used as setting for romantic encounters. I’m not a film buff but Indian friends have mentioned that several hit song sequences and famous movie scenes have been set there including humorous scenes from Padosan (apparently an early cult movie from 1968)

and if you want a taste of what they were like watch and listen to this song. ಸುತ್ತ ಮುತ್ತ ಯಾರು ಇಲ್ಲ. [You don’t need to understand Kannada the local language to get the drift]

Today the whole site is impressive but sadly just a shadow of what it was and it needs a big injection of Bollywood money to bring it back to a decent state. It’s currently run by Cauvery Irrigation Corporation a part of the state government but a major restoration and improvement project was announced in 2023 although there’s not much sign of it happening.

Apart from dealing with “deteriorating pathways, outdated fountain technology, obsolete lighting, inadequate infrastructure, and limited tourist amenities,” the Cauvery Corporation “has put forth a proposal to transform the tourist facilities at Brindavan Gardens into state-of-the-art amenities…”to elevate the existing Brindavan Garden to a world-class standard, thereby preserving the heritage of Mysore and the KRS Dam.”

from the local tourism site

Despite everything I was assured by people I spoke to there that despite its somewhat dilapidated state it still comes alive in the evenings and at festival times because not only are the gardens lit up with arrays of colourful lights but there is a laser Light Show when the fountains are synchronised with music, and run by an aquatic organ. Since most of the fountains were operating at a pretty feeble level, if they were working at all I can only assume that additional water was released from the dam to get them to function properly. If you like that sort of thing then you’ll easily find plenty of images and video footage to/ show that they do [or at least did] work in spectacular fashion.

Unfortunately there’s very little I can suggest if you want more information. There’re plenty of short video clips showing Brindavan but very little about its history. I may well come up with some more when I research Krumbeigel but in the mean time if anyone knows of anything else useful please let me know.

You must be logged in to post a comment.