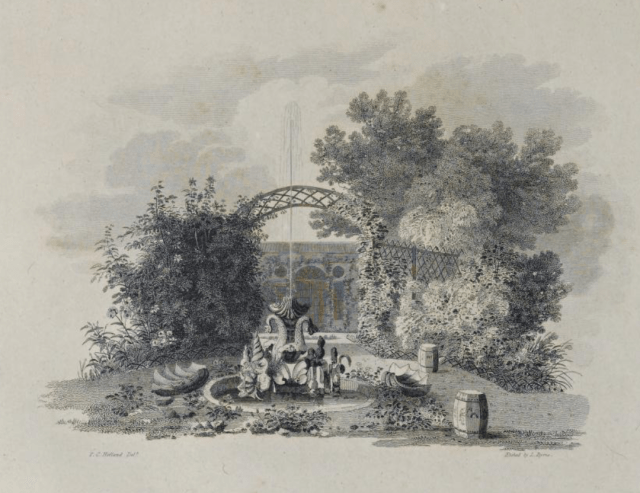

The Gothic Bower

A few weeks ago, purely by chance, I came across an illustrated guide written in 1816 for a garden called Whiteknights which was in its day probably the most famous garden in the country. The guide was so intriguing that since the estate is just a couple of miles from the centre of Reading I decided to pay a visit and see what, if anything was left.

Purchased in 1798 for George Spencer-Churchill, the Marquis of Blandford and heir to the Dukedom of Marlborough, Whiteknights became the site of reckless extravagance and outrageous entertainment. George was a magpie, collecting art, furniture, books, wine and rare plants and laying out magnificent gardens.

As you might remember from this earlier post he was so renowned a plantaholic that he had a family of Australian plants named in his honour. Unfortunately he was also such a spendthrift that he went bankrupt in 1819 and was forced to retire to Blenheim Palace [what a hardship!]. Whiteknights was later sold, and the house soon demolished with the ground divided up and developed. It’s now the campus of Reading University but hidden away there are still a few traces of the Park’s past splendour.

detail of A View of Whiteknights across the Lake, by Thomas Christopher Hofland, 1816

Image credit: University of Reading Art Collection

We know about the Marquis’s time at Whiteknights because he commissioned a guidebook from Barbara Hofland with engravings by her husband Thomas Christopher Hofland which described the estate, especially its gardens, in great detail, sometimes in extravagant prose and sometimes in excruciating poetry.

A descriptive account of the mansion and gardens of White-Knights : a seat of his grace the Duke of Marlborough published in 1819 stands record to the garden’s grandeur. Barbara Hofland’s language was flowery and effusive to say the least, and of course it praised the good taste of her patron. It was tempting to include long extracts from her descriptions but I don’t think many of us would have the patience to read them all, so I’ve tried to be selective just to give you a flavour. Its often so over the top that, by the end, I was wondering how much of it she actually believed herself…and it turns out that was prescient.

A descriptive account of the mansion and gardens of White-Knights : a seat of his grace the Duke of Marlborough published in 1819 stands record to the garden’s grandeur. Barbara Hofland’s language was flowery and effusive to say the least, and of course it praised the good taste of her patron. It was tempting to include long extracts from her descriptions but I don’t think many of us would have the patience to read them all, so I’ve tried to be selective just to give you a flavour. Its often so over the top that, by the end, I was wondering how much of it she actually believed herself…and it turns out that was prescient.

The illustrations in this post come from that book unless otherwise acknowledged.

The chapel

Whiteknights was reached from the main London to Reading road by a long “umbrageous path” which led past lodges and a 3-arched gateway into more open parkland. “A bold sweep ” of the road gave “a view of a most noble piece of water… beyond which we behold the house (a handsome modern structure) … On the right hand, the ruins of an ancient chapel appear, half veiled in a coppice of various trees…. a group of abele poplars of singular beauty, wave their long branches, and cast a soft shadow over the stream, which is here enamelled by water lilies, and inhabited by beautiful swans, which, proudly floating on their glassy empire, appear to give the stranger a stately welcome to the scene on which he more immediately enters, as a gentle ascent now leads him to the lawn”.

I’m sure by now you’ve got the drift – and we haven’t even started on the house and “beautiful and highly ornamented portion of the grounds which more immediately surround” it. I can already hear you mumbling “enough!” But there is more, much more.

The house had an ironwork verandah covered with “the most rare and fragrant exotics growing in classical vases of the finest forms,…which displays the botanical knowledge and interesting pursuits of the noble possessor.” The lawn in front was “of the purest emerald hue, enriched with plots adorned with fragrant flowers, rare shrubs, and light trees of every graceful form, which lead the eye by fine gradations to those distant clumps of massy foliage in the park”,

The view from the north front

And so on and so on in the same vein for several more pages as Hofland describes the views from the other fronts. Stop now I can hear you cry – we really don’t need to read about the “beautiful lake, on whose calm bosom the powers of vision repose with new delight. Thickly foliaged and lofty trees to the left, in their dark masses, form a majestic contrast to the shining waters, and give a bold outline to the picture. …[and on and on for another page] … At this point even Barbara admits that “The annexed view was taken from this side of the house, and will convey an idea of its character better than any description.” Thank goodness for engravings!

There then follows a detailed description of the rooms in the house before returning to the gardens and this is where you can see why Blandford deserves his reputation as a collector, and one can almost forgive Hofland’s prolixity. Part of the grounds were specifically called the Botanic Garden and were an ” unrivalled storehouse of Flora, guarded and adorned by four lofty cedars of Lebanon.” Sadly her husband is much more interested in drawing the many rustic garden buildings and seats than any of the plants or gardens so I’m reliant on other contemporary images for illustrations.

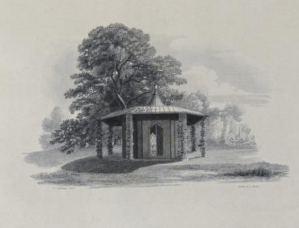

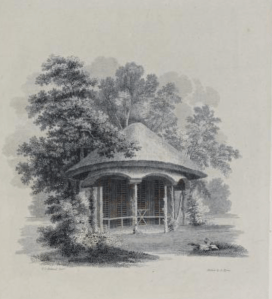

Some of the many rustic seats and shelters drawn by Thomas Hofland

It’s difficult to know how to convey the scale and complexity of the Botanic Garden, given that it included a large number of smaller enclosures as well as a range of buildings and the description takes the form of a circuit walk.

It was entered by an “oriental” arched gate “surmounted with crescents” and “covered with “luxurious” Jasmine, Clematis and Corchorus Japonica”. Round the perimeter was a wide border “entirely devoted to American plants… remarkable for their beauty or valuable from their scarcity.”

There were several lawn areas “of most exquisite verdure” most of which were ornately decorated with things like “baskets of exotic flowers, among which the Begonia with its richly lined leaves of red, and the Scarlet Sage, appear particularly brilliant’.

Around them were such things as “a delightful plot of Roses, which are surrounded by a broad border of Rock-work covered with Alpine plants, whose diminutive stems, tiny sparkling flowers, and fibrous or fungous leaves, opposed to the spreading branches of the mighty Oak, or the leafy honours of the Magnolia, add to the interest excited by each, and perfect the chain of vegetable existence.”

Lady Diana Beauclerc’s fountain

Another lawn, this time circular, had as its centrepiece an elaborate fountain designed by Blandford’s great-aunt Lady Diana Beauclerc, “and affords a fine specimen of the taste that lady so eminently possessed.” Judging by the lengthy description of dolphins, shells, seaweeds, lizards, and “fine specimens of sea weed, petrified fungi, brainstone, white and purple Fluorspar, blue John, spiral shells, rose-tinted conchs and nautili : in the interstices green creeping mosses, like vegetable emeralds,” her taste was certainly for the lavish and ornate. There were goldfish “sporting in the limpid element” of the fountain basin and around it was “a rich border of spars, pebbles, and fossils, amongst which grows the Dwarf or China rose, forming a margin which unites the beauties of the marine and vegetable world,” in a “fairy scene”

Some more of the rustic huts and shelters

This lawn was surrounded by trelliswork arches covered with “pendant clusters of the hop intermingle with the gay blossoms of the honeysuckle, which form canopies of unrivalled beauty. The garden thus encircled is luxuriantly enriched with China roses, scarlet sage, splendid dahlias and geraniums.”

Trellis and lattice work were other key structural features. There was a ” beautiful arcaded avenue” 198 feet long, on which honeysuckles and other creeping plants entwine their tendrils … a verdant triumphant arch, worthy of being the vestibule to the palace of Flora. More trellis supported “the Magnolia Wall” 20 feet high and 140 long, and “unquestionably unique, formed of Magnolia Grandiflora, in the highest state of perfection”

The Marquis clearly liked to take a seat when strolling round his estate. In the Botanic Garden alone there was a trellis-work “Open Hexagon seat …painted green, on which climbs the Corchorus and other Capreolates”, two “mushroom seats”, a Rustic Bower formed of Elm branches and “covered with a fragrant drapery of Honeysuckles and Jessamine” and the Gothic Bower, seen at the beginning of the post “profusely covered with Atragene Austriaca and Corchorus”.

An Ash Tent”formed entirely of the pendulous branches of a weeping Ash ” was “supported by light pillars entwined by Ivy : within and without are placed barrel seats of the finest Etrurian ware, with Garden chairs, Bronze tables, and every other elegant and useful article necessary for the perfect enjoyment of the scene around.”

There were a whole range of smaller gardens within the Botanic Garden complex. So many in fact that even a full list of them could fill half this blog post. They included the Duchess Garden, a ” horticular Bijou”, a “Japan garden”, a “Striped Garden where the most curious and beautiful foliage is presented on every side, the trees and plants being all of the variegated kind”, and one devoted to Dahlias, only recently been introduced to Europe, “in which every possible variety of this new and beautiful plant are seen in their highest splendour.

Garden buildings abounded too, including at least six greenhouses. An avenue of”luxurious exotics” led to the Temple of Pomona, which was “a superb Greenhouse” clearly used for more than just the “reception of rare plants” because it too had chairs and sofas and ” never did Luxury wear a more inviting aspect…

Nearby was the “Long Greenhouse” used to overwinter tender plants for use in the borders such as Geraniums; another for Cape plants and two more for Tropical plants.

Additionally there was a Conservatory “filled with all the most rare and exquisitely beautiful exotics”as well as “jars, vases, and bowls, of scarce, costly, and elegant china, whose brilliant hues and rich gilding mingling with the soft and glowing colours of their blooming inhabitants, form an assemblage of all that is most perfect in nature and art, and spread an air of enchantment over the scene it is impossible to describe.” although, of course, Barbara does try to do so at considerable length.

A separate “noble” orangery had recesses containing more sofas. “Through the middle runs an aisle of light arches, whose columns are encircled and their tops canopied by the rich foliage and scarlet flowers of the Bignonia Grandiflora, and other plants of equal beauty. There were of course also “numerous young orange trees, glowing with golden fruit and fragrant with blossoms,” and more orange trees in tubs surrounding it.

Yet another heated greenhouse contained” the most remarkable Aquatic plants from China, Egypt, and other distant countries.” It was “externally incrustated by beautiful rock-work, and the walls are latticed some feet from the ground, for the advantage of creeping plants. Elsewhere was the British Aquarium for “our native aquatic plants growing in perfection.” Like the other buildings it was for more than just plants. At its entrance were “two Bronze Vases of the finest form and most exquisite workmanship, lately purchased by the Duke of Marlborough from the gardens of Malmaison.” Even the water pump there was “finished with an urn ; two Bronze Eagles with extended wings form the water spouts, being the arms of the Noble Possessor, as Prince of the Holy Roman Empire.”

from Ackermann’s Repsoity 1820

https://archive.org/details/repositoryofarts1020acke/page/n315/mode/1up

Of course there were many specimens trees and shrubs including “Hemlock Spruce, whose descending branches sweep the turf… Magnolia Glauca, the Moutang or Piony tree, the Erica Multiflora in both its colours, the scarlet Azalea” and “a cedar of Lebanon worthy of the gardens of Solomon.”

Now you might think this was all just spending money on novel and rare plants for the sake of it, but George Spencer-Churchill really was interested in botanical science. He created a square Linnaean Garden, enclosed by protecting hedges where “every herbaceous plant is regularly classed, and the name of each affixed to the place of its growth.” It was described as a “scientific museum” although that didn’t stop it including a hexagonal Chinese temple… canopied and painted in two greens with good effect… supported by six arches, each of which is entwined by a distinct specimen of the Clematis : within are seats and stands for music.

Scanned from The Profligate Duke by Mary Soames [full reference below]. Notice that she doesn’t even attempt to map the Botanic Garden.

One path led in a long sweeping curve that ran alongside the public road round to the Wilderness, an area Hofland said was based on the thoughts of the philosopher and historian Jean-Francois Marmontel who she quotes: “All sides of this smiling scene agree without sameness ; the very symmetry is striking ; the eye roves without lassitude, and reposes without dullness ..,.nothing forced or laboured with too much art.”

Features of note included a rustic cottage, catalpa walk, a laburnum bower 1200 feet in length and a “rustic orchestra” designed for musical events.

There was a return to formality too with the French-inspired “Chantilly Garden” which in addition to its “Green paths, which intersect each other at right angles” and ” frequently meet at the foot of a towering Elm, or gigantic Oak”, also contained a rose garden and lots of other flowerings shrubs and plants.

The Rustic Bridge

Finally [you’ll be glad to hear!] there was a Grotto made of huge stones which stood at the head of the stream that fed two fountains before it became the ” noble river, and eventually far-spreading lake.” There were two bridges over it. One “so completely covered with Ivy and the Alexandrian Laurel, that we should not perceive we were passing the arch if we did not see the water ” and ” a rude Alpine Bridge…”supported and formed entirely of roots and branches of trees in their natural state, combined in the most simple yet ingenious and picturesque manner it is possible to conceive ”

The Grotto

I ought now to be honest and finish by admitting that not everyone agreed. with Barbara Hofland’s eulogy and to my surprise I’m not sure she herself did either.

The writer Mary Russell Mitford for example visited in 1807 and wrote to a friend…” I was greatly disappointed. The park, as they call it if about eighty acres, without deer, can be called a park), is level, flat, and uninteresting; the trees are ill clumped; the walk round it is entirely unvaried, and the piece of water looks like a large duck pond, from the termination not being concealed. If the hothouses were placed together instead of being dispersed they might make a respectable appearance; but, as it is, they bear evident marks of being built at different times (whenever, I suppose, he could borrow money for the purpose) and without any regular plan. Their contents might be interesting to a botanist, but gave me no pleasure.”

She went on: “He – the possessor of Blenheim – is employing Mr. Hofland to take views at Whiteknights – where there are no views; and Mrs. Hofland to write a description of Whiteknights – where there is nothing to describe… It is the very palace of False Taste – a bad French garden, with staring gravel walks, make-believe bridges, stunted vineyards, and vistas through which you see nothing.” And then comes the crunch-line: Thither did I go with Mrs. Hofland – …. the master was absent, and we had the comfort of laughing at it as much as we chose”

She went on: “He – the possessor of Blenheim – is employing Mr. Hofland to take views at Whiteknights – where there are no views; and Mrs. Hofland to write a description of Whiteknights – where there is nothing to describe… It is the very palace of False Taste – a bad French garden, with staring gravel walks, make-believe bridges, stunted vineyards, and vistas through which you see nothing.” And then comes the crunch-line: Thither did I go with Mrs. Hofland – …. the master was absent, and we had the comfort of laughing at it as much as we chose”

So I suspect that Barbara wrote so flatteringly just for the money. If so, the sad thing is that the venture was a financial disaster for the Hoflands because when the Duke went bust they were never paid. And on that surprising note I’ll finish this week and return to look at Whiteknight’s more recent history in another post soon.

So I suspect that Barbara wrote so flatteringly just for the money. If so, the sad thing is that the venture was a financial disaster for the Hoflands because when the Duke went bust they were never paid. And on that surprising note I’ll finish this week and return to look at Whiteknight’s more recent history in another post soon.

For more information, apart from the Hofland’s book the only other easily available places to start are Mary Soame’s biography of George Spencer-Churchill, The Profligate Duke. and Ian Cooke’s article “Whiteknights and the Marquis of Blandford”, in Garden History, Spring 1992.

You must be logged in to post a comment.