A view of the terrace at Enville

It’s now just over ten years since the Wedgwood Collection, one of the most important industrial archives in the world and a unique record of over 250 years of British art, was saved by the Art Fund from sale and dispersal.

It was gifted to the Victoria and Albert Museum and in 2019 they entered into a partnership with the World of Wedgwood to house the more than 80,000 works of art, ceramics, manuscripts and photographs in a purpose built free-to-visit gallery at Barlaston in the heart of the Potteries, and not far from Josiah Wedgwood’s home and factory at Etruria.

The collection offers a lot of evidence of the 18th century’s love of gardens and designed landscapes thanks largely to an Anglophile Empress.

Perhaps the most famous Wedgwood connection with gardens dates from June 1774 when a notice appeared in several London newspapers, informing the nobility and gentry that tickets were available to see ‘a Table and Dessert service now set out’ at Wedgwood’s ‘new rooms in Greek Street’. With this modest statement fashionable London society learnt about one of the most important and extravagant commissions to be carried out by Josiah Wedgwood and his business partner Thomas Bentley in what Wedgwood called “the noblest plan ever yet laid down or undertaken by any manufacturer in Great Britain”.

The service, now universally referred to as the ‘Frog Service’ because of the emblematic green frog on every piece, was commissioned by Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia for the new Chesme Palace near St Petersburg. Built in the then fashionable English neo-gothic style the palace was nicknamed La Grenouillere because of its location on a frog-filled marsh. Catherine requested that each piece of the 50 setting dinner and dessert service, should be hand-painted with different views of British scenery, although she left the style and decoration up to Wedgwood.

The service, now universally referred to as the ‘Frog Service’ because of the emblematic green frog on every piece, was commissioned by Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia for the new Chesme Palace near St Petersburg. Built in the then fashionable English neo-gothic style the palace was nicknamed La Grenouillere because of its location on a frog-filled marsh. Catherine requested that each piece of the 50 setting dinner and dessert service, should be hand-painted with different views of British scenery, although she left the style and decoration up to Wedgwood.

The order amounted to a total of 952 pieces (a number of spare pieces were included in case of breakages) decorated with 1,222 different topographically accurate views. These were chosen by Bentley and copied by a team of 30 artists employed at Wedgwood’s Chelsea decorating studios some specialising in the border decorations, others on the views. Each view was painted in black and sepia on a cream background with a splash of green enamel for the frog.

Wedgwood and Bentley worried at first that “all the gardens in England will scarcely furnish subjects sufficient for this set”, so they turned to topographical books, particularly Samuel and Nathaniel Buck’s Antiquities (1726-42) and existing engravings such as Thomas Smith’s views of Yorkshire and the Derbyshire Peaks and Chatelain’s prints of the gardens at Stowe, Chiswick and Kew. Yet others came from landowners who were anxious to have their property depicted on the prestigious service. If Bentley couldn’t find what he thought were suitable images of places he wanted to include then the firm commissioned them.

Each piece was numbered on the underside and listed the location of each view in a printed catalogue prepared by Bentley which was sent to the Empress with the bill for £2,290 12s 4d. It was a roll-call of every major landscape in Britain. There were ancient monuments including Stonehenge and Silchester, mediaeval castles including Bodiam and Harlech, monastic ruins such as Tintern and Kirkstall, Stately homes such as Castle Howard and Harewood, and newly created landscape parklands like Stowe and Blenheim. There were churches, geographic features including Fingal’s Cave and Ullswater and surprisingly contemporary views too of Plymouth docks, the Bridgewater canal, even the paper mills at Rickmansworth.

The Green Frog came in two designs. The dinner service had the frog’s shield surrounded by oak leaves while the dessert service was wreathed in ivy.

The ceramics were first made at the new Wedgwood factory at Etruria, Staffordshire which only opened in 1769. It was made of lead-glazed earthenware, rather than the more expensive porcelain, and then taken down to London to be painted at the firm’s decorating studio in Chelsea. The service took two years to complete and it was then put on display in London for two months. Amongst the visitors was Queen Charlotte and Wedgwood gained the title of Potter to Her Majesty. There was such interest that Wedgwood suggested they produce more pieces – but this time without the green frog – to be shown and sold from their London showroom.

It’s thought that 23 other pieces were not included in the final order because they were perhaps in some way imperfect, or not interesting enough to be included. Wedgwood wrote “I think the fine painted pieces condemn’d to be set aside, whether it be on account of their being blister’d, or duplicates, or any other fault, except poor & bad painting should be divided between Mr. Baxter & Etruria.” ‘Mr. Baxter’ was Alexander Baxter, an Englishman and member of the Russia Company, who was appointed Russian consul to London in 1773.

For a more detailed account of these set-aside pieces see “English Frog” an essay by Dr. Anne Forschler-Tarrasch Chief Curator of the Birmingham Museum of Art.

Dessert plate, of Queen’s ware; with ogee edges; painted in black with a view Painshill, Surrey’,

The view is repeated on an oval dish still in the Hermitage Museum, and it seems likely that this plate now in the British Museum, was a duplicate, and never left England. Three other view of Painshill were used on dishes in the service

When the service in its 22 crates finally arrived in St Petersburg in the autumn of 1774 it was displayed in the palace as a spectacle for visitors. The majority of it has survived and is now in the Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, so these days it is mainly Russians who get to enjoy this pictorial record of 18th-century Britain which is almost a statement of Georgian soft power.

Although the service had been made to serve only 50 persons, it contained 288 flat plates, 120 soup plates and 144 dessert plates. Even with that number its almost certain that extra pieces are likely to have been required for the even larger parties that were known to have taken place . These were probably not made by Wedgwood but instead by the imperial porcelain factory in StPetersburg in the style of the Wedgwood service.

What no-one knows is how often the service was used but it’s thought that while Catherine admired it she probably didn’t actually use it that often. In fact if the pieces, were to be properly appreciated, it would have been much easier for them to be examined when the service was on the shelf rather than in use. In any case since the painting was done with over the glaze it would not handle much wear and tear.

After her death it seems to have been put into storage and forgotten about, and only “rediscovered” in about 1909 in an underground pantry in one of the palaces at Peterhof, a

room that had not been opened for perhaps seventy years or more.

For more on the later story of the Frog service see Gabriel Newfield’s article Josiah “Wedgwood’s Green Frog service: Its life in Russia from 1774 to the present day” in Occasional Paper 5 of the London Ceramic Circle.

As a money maker, it was a failure. Wedgwood probably only made about £100 profit from the whole venture. Catherine paid a little more than £2,700 while the service actually cost £2,612 to create. The cost of the manufacturing was almost negligible – apparently just £51 – but the decoration was expensive and accounted for the bulk of the rest. But, of course, Wedgwood was’t that worried because as an advertisement, it was priceless.

Whilst Catherine’s frog service may have been the most prestigious work produced by Wedgwood it certainly wasn’t the only garden or landscape-inspired work coming out from his workshops. Nor was it the most colourful.

At the same time Etruria was creating Catherine’s Green Frog service Wedgwood was also producing a range of other plates portraying English country houses and their surroundings, which were painted in realistic colours.

It was Josiah Wedgwood himself who proposed creating a collection for posterity : ‘I have often wish’d,’ he wrote, ‘I had saved a single specimen of all the new articles I have made, and would now give 20 times the original value for such a collection. For 10 years past I have omitted doing this because I did not begin it 10 years sooner. I am now, from thinking and talking a little more upon this subject … resolv’d to make a beginning.’

But there are many other things of horticultural interest in the collection, although of course they also tell of contemporary politics, society, science and art. For example, this coffee pot shows not only how coffee drinking was spreading among the middle class at home but also how naturalistic forms, such as cabbages, melons and cauliflowers became popular in Georgian Britain, as part of the rise of the rococo style.

Such Rococo-inspired wares formed a very small part of early Wedgwood production, but they are very distinctive because of the brilliant green colouring. This is thought to have been developed by Wedgwood himself because his formula for ‘A Green Glaze to be laid on common white biscuit ware’ is listed as number 7 in his Experiment Book in 1759. It also demonstrates Wedgwood’s constant search for innovation although the main body of the teapot is cream ware which soon to be renamed Queen’s ware, after Wedgwood secured an order for a tea set ‘with a gold ground & raised flowers upon it in green’ for Queen Charlotte. The following year “the Queen was pleased to give her name and patronage, commanding it to be called Queensware, and honouring the inventor by appointing him Her Majesty’s Potter”.

Teaware also has much social significance. Although tea had been introduced into Britain after the Restoration it remained an expensive luxury item and didn’t become a fashionable social drink until well into the 18th century when it was prepared in front of guests. Its popularity grew rapidly after import duties were abolished in 1784. The teapot below is based on an engraving by Robert Hancock known as “The Tea party” which shows a well-dressed couple having tea in a garden, attended by a young black man servant who is shown pouring hot water from a kettle into the pot.

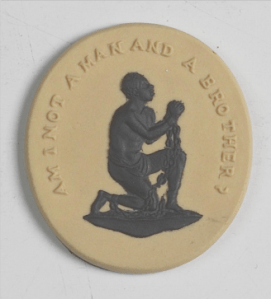

The design had a particular resonance for Wedgwood himself because he is not only rightly celebrated as a pioneering innovator in the field of ceramics, but also importantly as a social reformer and philanthropist, who took a leading role in the anti-slavery movement, and in factory reform.

About 10,000 Africans are estimated to have been living in 18th century England, mostly enslaved or most working as domestic staff. For their affluent owners these African slaves or servants were status symbols who, like the tea they were drinking, offered ‘exotic associations’.

Wedgwood’s other interests embraced a wide range of topics from art and design, the improvement of transport by road and canal, cost accounting, education, factory management, new production methods, entrepreneurial activities and international marketing.

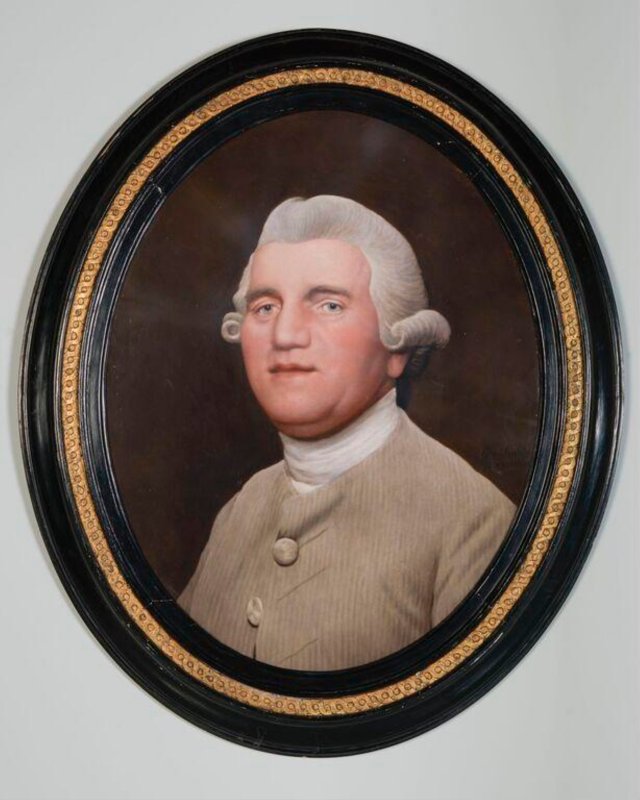

He was a member of the Lunar Society which also included James Watt, Matthew Boulton, Erasmus Darwin, and Joseph Priestley. He knew artists like Joseph Wright from Derby, and George Stubbs who painted the Wedgwood family in the grounds of Etruria Hall.

Etruria Hall, the mansion he built for himself and his family, had about 4 acres of grounds designed by William Emes, with a Chinese bridge, summer house, fish ponds and nurseries, but there is no early plan of the estate and the precise layout cannot be determined. The house has endured many vicissitudes over the years but is now a hotel, having been used as the centrepiece for the Stoke Garden Festival in 1986.

Finally I wonder if Wedgwood ever sat in Etruria Hall and considered how his dinner and dessert services were received in Russia. Michael Prodger writing in the New Statesman in 2021 conjured up a nice answer to that question saying that “however jaded the imperial appetite might have been, Catherine, in distant Muscovy, would have polished off her meal simply to see which new British scene was waiting for her underneath her fricassees and syllabubs.” Given that there were 288 flat plates, 120 soup plates and 144 dessert plates it would have taken her a long time to discover them all!

You can search the Green Frog Service via the Hermitage website, but you’ll probably need to use a translation service such as Reverso to do so! Otherwise if you want to know more then good places to start are the very detailed history of the Frog Service in Gabriel Newfield’s article Josiah “Wedgwood’s Green Frog service: Its life in Russia from 1774 to the present day” in Occasional Paper 5 of the London Ceramic Circle. If you’re feeling rich then you could splash out on Michael Raeburn’s 1995 book The Green Frog Service : Wedgwood & Bentley’s Imperial Russian Service, currently available on Abe Books for £495 [yes not £4.95]

You must be logged in to post a comment.