Happy Daffodil Day!

Daffodil Day is celebrated annually on March 22nd and has been a key fundraising event organised by cancer charities across the world since the 1950s because the show of bright colour so early in the year represents hope and a sign of renewal.

I suspect we all feel that when we see them. Maybe it’s the time of year when we need some strong cheerful colour around us – but in that case why don’t we feel the same way about equally colourful and loud forsythia?

What is it about daffodils? They’re planted everywhere and anywhere, often vulgar and brash in colour and are probably our commonest bulb in both senses. Yet it’s rare to find someone who dislikes their show and their often brazen visual intrusion. Perhaps it’s because as Picasso said: “no one has to explain a daffodil. Good design is understandable to virtually everybody”. The fact that most people with “taste” prefer the smaller wild species is no reason to stop the rest of us liking a bit of golden vulgarity!

It used to be said that you could have any colour of daffodil you wanted as long it was yellow or white, but intense breeding programmes have introduced green, orange, pink and even an almost red, as well as more and more unusual flower formation and shapes. That’s certainly shown in the International Daffodil Register maintained by the Royal Horticultural Society. The last edition of the Register, published in 2008, had over 27,000 named cultivars. Since then more than 3,000 more have been added in supplementary lists.

The Register groups the narcissus family into 13 divisions, several of which are further subdivided. However as a look through any bulb catalogue will show you, many are remarkably alike in form, shape and colour.

Not all to everyone’s taste I’m sure, so if you like your daffodils a traditional shape and a standard colour then please avert your eyes to the following few photos of some recent cultivars, and scroll down rapidly to read the rest of the post!

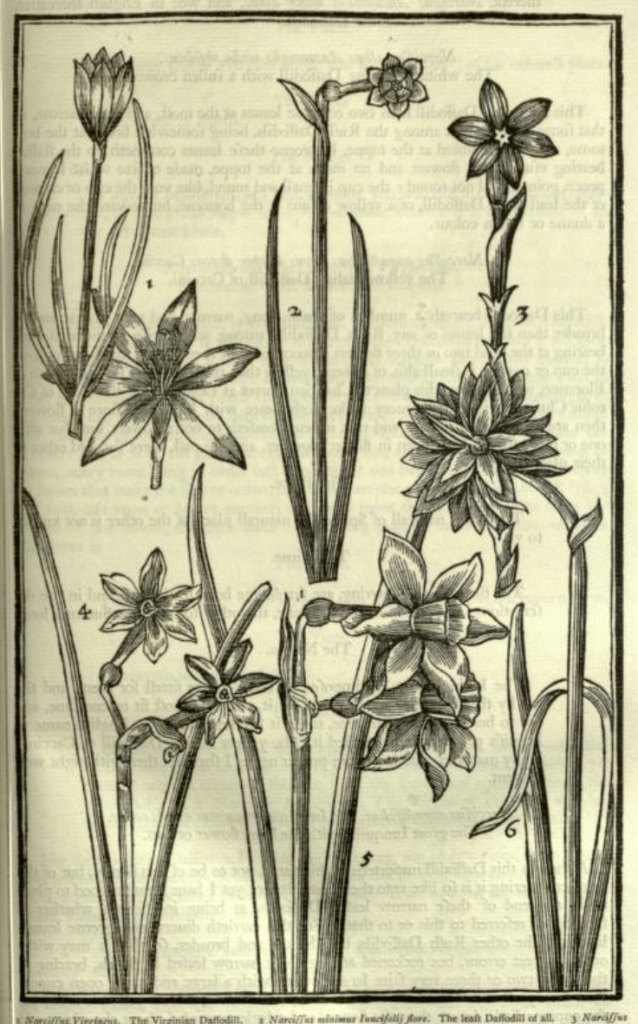

This lust for new varieties is not new. Daffodil collecting and breeding has a long history, even if the concept of hybridising wasn’t understood at the time. For example, in his Herbal of 1597 John Gerard reports the “double white Daffodill of Constantinople was sent into England unto the right Honorable the Lord Treasurer, among other bulbed flowers.”

Thirty or so years later in, Paradisus in Sole John Parkinson was able to list nearly 100 varieties of daffodils that grew in English gardens with evocative names such as “the great double purple ringed daffodil of Constantinople”, “the white mountain daffodil with ears” and “the great yellow Spanish bastard daffodil”.

Parkinson also grew daffodils from seeds given to him by his friend Dr Flud who had collected them in the university garden in Pisa.

There was clearly rivalry and competition between plant collectors even then, and Parkinson tells the story of a strange bulb that was presumably grown from seed by Vincent Sion, who was born in Flanders and so was probably a Huguenot refugee. Sion lived on Bankside in London and, like all good gardeners, liked to share his treasures. He eventually gave a few bulbs of his new discovery to both Parkinson and George Willmer of Bow. But, Parkinson says, Willmer wasn’t quite as generous and “would needes appropriate it to himself as if he was the first founder thereof and call it by his own name: Willmer’s Double daffodil”. More recently it has been re-appropriated in Sion’s memory.

Incidentally Parkinson also has a really straightforward answer to the simple question that’s often asked, about the difference between narcissus or daffodil: “Many idle and ignorant Gardiners..do call some of these Daffodils Narcisses, when as all know that know any Latine, that Narcissus is the Latine name, and Daffodil the English of one and the same thing.”

Of course, even before Parkinson, the daffodil was a frequent subject in Tudor and Jacobean writing, although there were many spelling variants. Shakespeare wrote of “Daffodils that comes before the swallow dares, and takes the winds of March with beauty” [Winter’s tale Act IV Scene 3] while “The Daffadill most dainty” comes from Michael Drayton’s The Muses Elizium.

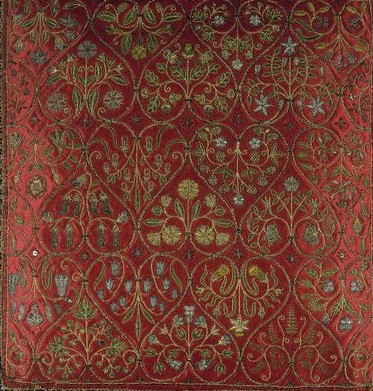

The flower was also used in fashion and furnishings too, as can be seen, for example, in this cushion embroidered with wild and garden flowers and plants…

…while the cushion cover above is made up of a series of smaller individual motifs known as ‘slips’ which were then sewn onto a backing cloth. Each depicts a popular subject, particularly naturalistic plants and animals which have been stylised in order to suit the overall design.

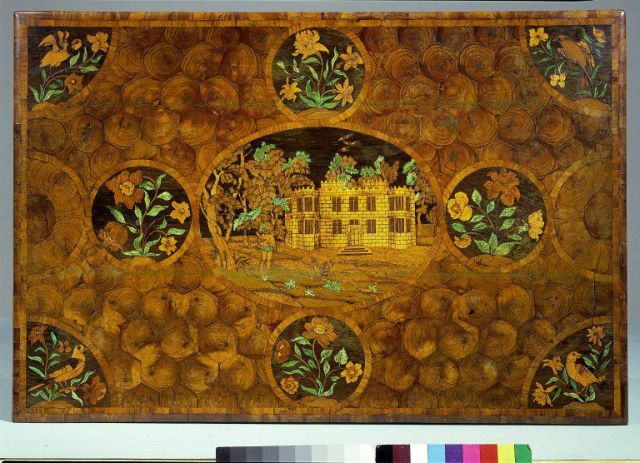

Marquetry Table top showing Wingerworth Hall, with insets of roses, anemones and daffodils. c.1674.

V&A W.53:1, 2-1948

And, at a slight tangent, it can’t be everyday that a piece of furniture is evidence for a historic house and garden, but here is a marquetry portrait of Wingerworth Hall in Derbyshire complete with its turrets and battlements. The house was built in the 1580s and bears similarities to the work of Robert Smythson, who designed nearby Hardwick Hall. The table top provides a unique representation of the original Wingerworth because it was to be rebuilt in the 1720s and then demolished in the 1920s. The circular compartments contain sprays of flowers, including some daffodils.

But daffodils fell out of fashion, difficult though that is to imagine, probably because they were regarded as wild flowers and so not worthy of a place in the garden. They do occur occasionally in textile designs such as this dress fabric designed by William Kilburn from his album of watercolour designs now in the V&A but it is the exception that proves the rule.

A revival of interest in the horticultural use of the daffodil family started in the early 19thc and although I don’t have time or space to go into a detailed history of daffodil breeding here I’ve picked out a few key figures to show their expertise and enthusiasm. Perhaps the first to take an interest was William Herbert who was a Church of England clergyman, finally becoming Dean of Manchester. As an earlier post showed he was fascinated by bulbs of all kinds and successfully cultivated several new daffodil hybrids as well as pioneering new ways of classifying them. However it was several decades before the daffodil stopped being seen as a wild flower that had no real place in the garden and that meant that there was little commercial demand.

“The fine varieties of Narcissus represented in the accompanying plate are seedlings raised by E. Leeds, Esq., of St. Ann’s, Manchester, a gentleman who has been for many years engaged in the cross-breeding of this tribe of plants, and who has originated many distinct and beautiful varieties.”

The Gardener’s Magazine of Botany, Horticulture, Floriculture, and Natural Science, 1851.

Edward Leeds [1802-1877] turned his garden near Manchester into an experimental site where he not only grew and hybridised daffodils but many other species of plants. He also kept a herbarium and corresponded with other collectors all over the world. There are still 192 daffodil cultivars associated with him on the International Register.

For more on Edward Leeds see this article by Joyce Uings

After Leeds died his collection was eventually bought by Peter Barr a Victorian seedsman and nurseryman who I’ve written about before. He wrote enthusiastically about daffodils, and published a list of 361 cultivars in Ye Narcissus or Daffodyl Flowre and hys Roots, with Hys Historie and Culture (1884).

Peter Barr

18xx-1909

Barr persuaded the RHS to hold the first Daffodil Conference in the conservatory in its garden in South Kensington. He argued that “The Narcissus… is now reasserting its position, and claiming its proper place in the general economy of border decoration, and as a cut flower for furnishing vases”. The Conference led to the establishment of the RHS Daffodil Committee which oversaw the new taxonomic arrangements I mentioned earlier.

from Barr’s Yea Narcissus

Barr put daffodils into commercial mass production from his nursery at Long Ditton near Surbiton in Surrey which became famous for the magnificent displays they put on, and really helped make the daffodil the most popular spring flower. After his retirement he spent seven years touring the world lecturing on daffodils. So it’s not surprising that Gardeners Chronicle named him the Daffodil King.

Sarah and Robert Backhouse

Other prominent proponents of daffodil breeding came from the Backhouse family. William Backhouse [1807-1869] began collecting and breeding daffodils and 3 of his children continued that interest. But it was his son Robert and daughter-in-law Sarah who pursued it with an absolute passion. Sarah served on the newly established RHS Daffodil Committee and was awarded the Barr Cup for her hybridising skills in 1916. They registered 58 new varieties and their son William another 30. Two years after her death in 1921 Robert bred the first daffodil to have a pink trumpet naming it in his wife’s honour. It was selling for £20 a bulb in 1926. More information about the Backhouse family on the Backhouse Rossie estate website

In Scotland Major Ian Brodie, the 24th Laird, inherited the Brodie Castle estate in 1889 and then used the walled garden to experiment with breeding daffodils. Although he produced thousands of hybrids, only 185 met his high standards, although other gardeners have continued to use and register new cultivars based on his original creations so that there are now about 400 varieties of Brodie daffodils. There is a lot more information about Brodie on the National Trust for Scotland’s webpage about him.

But there were plenty of other early collectors, growers and hybridisers of daffodils all round the country. For example three others based around Presteigne in Radnorshire, Powys are the subject of an article by historian Catherine Beale. If you know of any other good research on other local growers or the industry’s history in general then please let me know.

The work of Barr and the Backhouses led to a strong commercial industry developing in several parts of the country and some still survive – notably in Cornwall – despite strong competition from cheap flower and bulb imports. To see how that’s done it’s worth taking a look at the websites of Jack Buck Farms near Spaulding where 250 acres are devoted to daffodils, and Fentongollan Farm, near the River Fal which grows over 400 varieties of daffodil, including many that are new, unique and rare.

The UK remains the largest producer in the world of daffodil cut flowers with sales of about £100 million a year, and a further £10 million in bulb sales. Cornwall grows an estimated 80% of the daffodils that are sold as cut flowers globally, harvesting around 900 million stems of daffodils annually. They are all picked by, hand with more than 2,700 daffodil pickers required to work in Cornish fields every season, many of them temporary workers from overseas. The industry has been under much greater pressure since labour restrictions were introduced following Brexit. Golden Harvest, by Andrew Tompsett [2006] tells the story of the Cornish industry with lots of photos and family stories.

The UK remains the largest producer in the world of daffodil cut flowers with sales of about £100 million a year, and a further £10 million in bulb sales. Cornwall grows an estimated 80% of the daffodils that are sold as cut flowers globally, harvesting around 900 million stems of daffodils annually. They are all picked by, hand with more than 2,700 daffodil pickers required to work in Cornish fields every season, many of them temporary workers from overseas. The industry has been under much greater pressure since labour restrictions were introduced following Brexit. Golden Harvest, by Andrew Tompsett [2006] tells the story of the Cornish industry with lots of photos and family stories.

As interest in daffodil growing and then hybridising revived from the mid-19thc onwards, so a parallel increase can be seen in their use as a decorative motif. By the time the Daffodil Society was founded in 1898 daffodils were everywhere in the decorative arts. It was a real case of art imitating nature – or rather horticulture.

Prominent amongst the proponents was William Morris and his associates who took up floral themes for their fabric and wallpaper designs and there are several with a daffodil theme.

One by Lewis Foreman Day is unusual in that it shows not only the flowers and foliage but the bulbs and roots too.

Walter Crane, the artist and writer of children’s books, also produced several floral textile wallpaper and even carpet designs involving daffodils and other wild flowers. For more about him see this earlier post.

Apart from the contemporary fascination with daffodils it also reflects the revival of interest in wild flowers generally, and their reinstatement as features of garden planting which had been started by William Robinson in The Wild Garden [1870] and later The English Flower Garden [1883].

Many of these designs, particularly, those of Morris and his company, have been in continuous production ever since suggesting that the revival of interest in wild flowers was not just a passing phase in horticulture but one which, despite some vagaries of fashion persists strongly today.

As a result of all this interest daffodils began to be exhibited at local flower shows all round the country, and in 1898 the Daffodil Society was established with Robert Backhouse and Ellen Willmott amongst its vice-presidents. It is still flourishing as a quick look at its website will confirm.

Nowadays if you want to see a wide variety of daffodils then, apart from dedicated daffodil shows, many gardens organise Daffodil Days – and there are now six National Collections. Scotland has three of them. A collection of Backhouse family raised daffodils are grown at the Backhouse Rossie Estate in Fife. Another collection of those cultivars associated with Ian Brodie and Brodie Castle is cared for there by the National Trust for Scotland. The third collection is wider in scope covering any and all cultivar bred before 1930. Based in Ross-shire it’s run by Duncan and Kate Donald who sell their surplus stock to keen collectors.

In England Springfields Horticultural Society in Lincolnshire runs a collection with over 400 cultivars and species. In Sussex the local branch of Plant Heritage curate a collection of cultivars bred & introduced by Noel Burr, while the local branch in Suffolk care for one based around varieties bred & introduced by the Rev G H Engleheart, a country clergyman who introduced some 700 named varieties starting in 1889.

But how on earth I could write about daffodils without mentioning a certain well -known poem. I confess that obviously Wordsworth had been on my list of possible daffodil references but quickly rejected as too trite and hackneyed but then I remembered a Stephen Collins cartoon that I’d cut out and put into a bulb encyclopedia, so thanks for reading this far and I hope it makes you smile

For more information on Daffodil Day itself try Awareness Days. For Daffodils try Noel Kingsbury’s Daffodil: The Remarkable Story of the World’s Most Popular Spring Flower. By his own admission he’s not a “daff nut” but he has a fascination with social history and a very readable style. And the photographs are wonderful – they might even help you tell some of those 30,000 varieties apart!

Otherwise the best places to start on the flower are the Daffodil Society where you’ll find further links to many other daffodil related sites including growing tips, places to visit, a massive photo collection, local groups and the history of the daffodil. It’s also worth looking at Daffnet, a discussion forum for daffodil enthusiasts around the world.

You must be logged in to post a comment.