Appearances can be deceptive. A couple of days ago I took a train out into what was once the countryside surrounding Lisbon, hoping to see a garden that I’d mentioned in passing in an earlier post. Ten minutes stroll from a dreary concrete suburban station I found myself outside a very long largely single story building painted pale blue. My first thought was is this going to be worth the effort?

Appearances can be deceptive. A couple of days ago I took a train out into what was once the countryside surrounding Lisbon, hoping to see a garden that I’d mentioned in passing in an earlier post. Ten minutes stroll from a dreary concrete suburban station I found myself outside a very long largely single story building painted pale blue. My first thought was is this going to be worth the effort?

But as I said appearances can be deceptive. Once through the door everything changed because the palace of Queluz is one of the best Rococo buildings and gardens in Europe. Sometimes called the Versailles of Portugal the palace and its gardens were a real surprise.

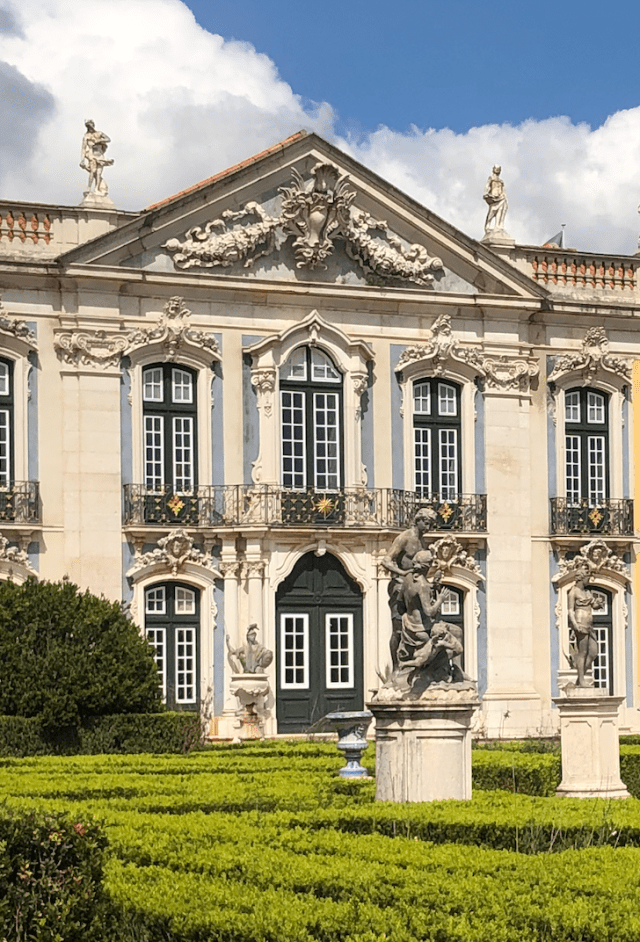

Behind the unexceptional street facade were ornate and fanciful interiors [to put it mildly] while the rear elevations of the palace are equally colourful and playful, and overlook a series of very grand gardens containing more statues than I think I’ve ever seen gathered in one place – apart possibly from the sculpture gallery of the V&A or maybe a Victorian cemetery!

Part of the street facade

as usual the photos are my own otherwise acknowledged

Less than ten miles from the centre of Lisbon Queluz was built as a summer retreat for Pedro of Braganza, the future Pedro III. Work began in 1747 under Portuguese architect Mateus Vicente de Oliveira but came to an abrupt halt after the catastrophic earthquake that destroyed Lisbon in 1755. Rebuilding the devastated city obviously took priority and led to an influx of craftsmen from all over Europe, but particularly France, to help. They bought the latest fashions in architecture and decoration to the somewhat backwater court of Portugal and the results were obvious when work restarted at Queluz. As a response to the earthquake the planned building was reduced in height and bulk, and is in large part single story, although since it sits on a gentle slope there are two and even three stories pavilions mainly on the rear side.

Unfortunately I don’t have time or space here to talk about the interiors but they’re definitely worth checking out. They’re a mix of the formal and the fantastic and include something like a Hall of Mirrors, somewhat smaller in scale than that at Versailles, a lot of Chinoiserie and tiled rooms and corridors many showing links to the Portuguese empire in Brazil and Asia, and all probably paid for with the discovery of Brazilian gold.

Unfortunately I don’t have time or space here to talk about the interiors but they’re definitely worth checking out. They’re a mix of the formal and the fantastic and include something like a Hall of Mirrors, somewhat smaller in scale than that at Versailles, a lot of Chinoiserie and tiled rooms and corridors many showing links to the Portuguese empire in Brazil and Asia, and all probably paid for with the discovery of Brazilian gold.

Many of the rooms open directly onto the gardens that lie behind the palace. The plain but classically inspired rear “Ceremonial Façade” is a masterpiece of “light touch” Baroque or as Xan Fielding described it in Great Houses of Europe “the decoration … follows an irregular pattern of whorls and curlicues suggestive of metalwork or even icing-sugar. The general effect indeed – and this analogy is not intended to be pejorative – is of a very expensive birthday-cake.”

The ceremonial facade

Oliveira had trained in France and now called in one of his former tutors Jean-Baptiste Robillion to assist with some of the building work but also to take charge of laying out the gardens, although he delegated much of that to a Dutch gardener Gerald van der Kolk about whom I can find no further information. It was Robillion who had originally trained as a goldsmith, who took over most of the work when Oliveira returned to help with reconstruction there. He added the large wing on the western end of the palace, now known after him, with its grand staircase down into the gardens.

The Robillion pavilion and staircase

In 1760 Pedro married the heir to the throne, his own niece Maria [not sure how they got that past the Catholic Church] and they made Queluz their principal residence even before it was finished. After Peter’s death in 1786 his widow ascended the throne as Maria I but became mentally unstable and so the palace became a sort of posh prison for her. Her son, John became Regent and made Queluz the official royal residence which it remained until Napoleon invaded Portugal and the royal family fled to Brazil.

The French commander Jean-Andoche Junot, then moved into their palace and continued to develop the building and gardens, including planting stands of magnolias and mulberries several of which still survive. On the royal family’s return from exile in 1821, Queluz became the home of Queen Carlota Joaquina, and she lived there in great style before she died in 1830. She even installed a menagerie in the rooms opening on to the terrace below the Robillion wing. After her death Queluz fell out of favour and in 1908, just two years before the monarchy was overthrown, it was given to the state.

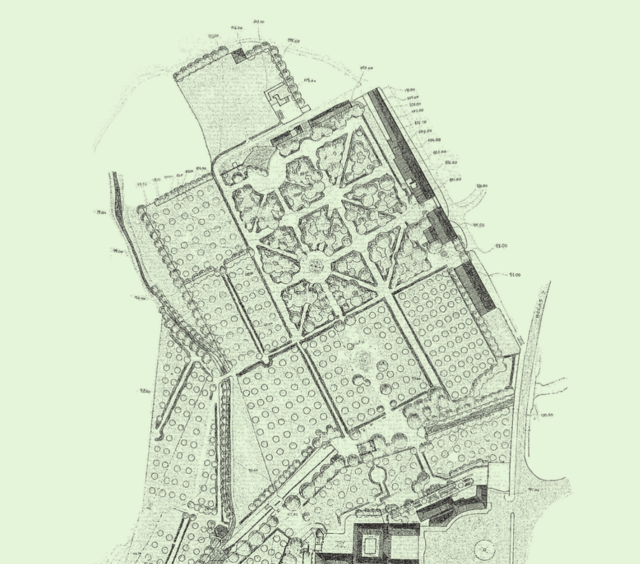

Let’s take a tour of the gardens beginning with the large area known as the New Gardens.

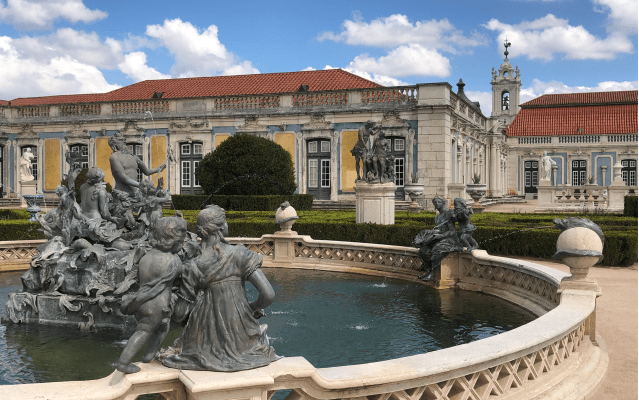

The Neptune Fountain

These were laid out in formal style between 1765 and 1775. There are hedged walkways and compartments with ornamental orange groves and bosquets between them and a range of ponds with a complex system of fountains supplied by a large cistern at the top of the garden slope.

The largest of these is an octagonal basin dating from 1764 known as the Medallion Fountain, but there is also an impressive Neptune Fountain with a series of tritons surrounding an earlier statue of the sea god moved to Queluz from another garden as late as 1945.

On one side are the stables, now used as a riding school, and a small bullring designed by Oliveira. Recent storms have caused a lot of damage to the mature trees and several sections of the New Gardens have been closed off as a result.

Turning back towards the palace there’s another marble basin surrounded by yet more marble busts and a series of lead figure groups by John Cheere, the London lead sculptor including Cain and Abel, “Aeneas and Anchises” and the “Abduction of Persephone”. For more on Cheere see this earlier post.

The other half of the gardens – the formal parterres next to the palace, The Grove , and in the bottom left corner, the Botanic Garden

The central bridge

Nearby, and close to the bottom of the Robillon staircase is the Tiled Canal which must rank as one of the most bizarre of any garden feature imaginable. A deep tile-lined channel 115 metres long with a stream running through it is crossed by a central bridge flanked by marble sculptures representing Mercury – the messenger of the gods – and Ceres – the protector of agriculture; and by two more lead sculpture groups by Cheere representing Bacchus and Ariadne and Venus and Adonis. A second bridge is a modern replacement for a Chinese pavilion which once stood astride the canal and which was used by chamber musicians to entertain the royal family.

The canal was designed to be dammed to provide a shallow boating lake where those afloat could glide past and admire the tiled landscapes and seascapes which date from 1755. But it was grander than just rowing boats because, as Lord Kinnoul, the British Ambassador at the time reported, the canal was used for fêtes champêtres, during which fully rigged ships would sail in processions with figures aboard in allegorical costumes.

In 2004 the canal became the focus of a World Monument Fund project when the 40,000 tiles that line it were digitally mapped to review their condition and to suggest a conservation programme. As you can see from the photo above this is still ongoing.

An aviary in another paet of the garden

The canal leads into the southern parts of the Lower Gardens which run along the valley floor. The lightly wooded area was used for games, and had a range of ephemeral pavilions including aviaries as well as more ponds and yet more statues.

A flat sunken area which looks as if it might have been a bowling green was in fact for the traditional ball game “Jeu de Paume” (the Palm Game) which involves throwing a leather or woollen ball with the palm of the hand and appears to have some similarities to the Basque pelota or even squash, although this was played outdoors and without walls.

The grass court for pela or Jeu de Palme

The court lies between the stream and The Grove, a typical feature of 18th-century garden design, made up of stands of trees, surrounded by box hedges of varying heights and crossed by paths in a geometric pattern and containing lots of seats and statues. Almost all the trees in these sections were ordered from Holland and were originally topiarised.

The court lies between the stream and The Grove, a typical feature of 18th-century garden design, made up of stands of trees, surrounded by box hedges of varying heights and crossed by paths in a geometric pattern and containing lots of seats and statues. Almost all the trees in these sections were ordered from Holland and were originally topiarised.

The Prince’s kitchen garden

In one of the clearings is an area known as the Prince’s Kitchen Garden, laid out in the late 19th century, where both common and exotic vegetables were grown in box edged beds. It was part of the royal family’s interest in botany which is better revealed in the adjacent area.

.

Tucked away in the furthest corner of the garden, across the stream and next to one of the former rear entrances to the palace is the Botanic Garden. This was founded in 1769 and had, as in many much earlier botanic gardens, four main planting areas one for each of the four continents. All were laid out according to the “new” Linnaean system so trying to try to reconstitute the “natural world”, but also reflect the order, reason and method characteristic of scientific thought at the time of the Enlightenment. There were also four greenhouses used to grow pineapples, which were the particular favourite of King Pedro. They’re growing there again now.

Tucked away in the furthest corner of the garden, across the stream and next to one of the former rear entrances to the palace is the Botanic Garden. This was founded in 1769 and had, as in many much earlier botanic gardens, four main planting areas one for each of the four continents. All were laid out according to the “new” Linnaean system so trying to try to reconstitute the “natural world”, but also reflect the order, reason and method characteristic of scientific thought at the time of the Enlightenment. There were also four greenhouses used to grow pineapples, which were the particular favourite of King Pedro. They’re growing there again now.

Later the area changed use several times until in 1983 everything was washed away in disastrous floods. At this point archaeological excavations were carried out and the decay eventually taken to restore the site to its 18thc layout and purpose using the 1789 catalogue of plants grown there. In 2018, the reinstatement won the Europa Nostra conservation award.

Crossing back over the stream and heading a short distance through formal but light woodland the path leads to another bizarre construction: a monumental and completely artificial rock cascade.

Crossing back over the stream and heading a short distance through formal but light woodland the path leads to another bizarre construction: a monumental and completely artificial rock cascade.

This was built in the 1770s. and supplied by a complex hydraulic system. At the top, there is a large water reservoir and a balustraded veranda, decorated with several stone and yet more lead statues by John Cheere. Water spouts mainly from the central figurehead and the two phoenixes standing on the sides.

On the way back to the palace there’s a so-called labyrith garden, which can see seen looking over the balustrade on  the terrace.

the terrace.

Xan Fielding adds a lighter touch telling us that it was here that “ in hot weather the mad Queen Maria would sit on the edge of a fountain with her legs plunged in the water – no doubt in the very position of the two lead figures that can be seen on the edge of the Neptune fountain today. Here too, along the scented box-hedged alleyways, the eccentric William Beckford once ran races with the maids of honour of the Queen’s daughter-in-law, Carlota Joaquina, thereby gratifying at one and the same time his aesthetic sensibilities and inordinate love of royalty.”

Xan Fielding adds a lighter touch telling us that it was here that “ in hot weather the mad Queen Maria would sit on the edge of a fountain with her legs plunged in the water – no doubt in the very position of the two lead figures that can be seen on the edge of the Neptune fountain today. Here too, along the scented box-hedged alleyways, the eccentric William Beckford once ran races with the maids of honour of the Queen’s daughter-in-law, Carlota Joaquina, thereby gratifying at one and the same time his aesthetic sensibilities and inordinate love of royalty.”

The dozens of marble statues, mainly of the seasons or mythological figures, were imported from Italy while the lead sculptures in the garden were all commissioned from John Cheere in 1755 and 1756, and comprise the largest single-garden collection of his work. In 2004, the World Monuments Fund began a program to restore these Cheere sculptures as well as some of the other features of the garden, including at least 14 of the fountains.

The dozens of marble statues, mainly of the seasons or mythological figures, were imported from Italy while the lead sculptures in the garden were all commissioned from John Cheere in 1755 and 1756, and comprise the largest single-garden collection of his work. In 2004, the World Monuments Fund began a program to restore these Cheere sculptures as well as some of the other features of the garden, including at least 14 of the fountains.

Slightly sunken and to the right as you look at the palace is the Malta Garden, constructed between 1758 and 1765 and so-named because King Pedro was Grand Prior to the Order of Malta.

Between 2017 and 2018, both these parterre gardens were restored to their 18thc appearance which included returning the four ponds to their rightful place in the corners from other areas of the gardens to which they had been moved, and returning the statues to the original locations chosen by King Pedro III.

On the day we visited Queluz was virtually empty, although I suspect in high summer it has quite a few visitors. Unfortunately the peace and quiet of the garden is, in some places, disturbed by the roar of motorway traffic that runs just outside the wall on one side and the railway [luckily largely hidden in a cutting] at the opposite end of the garden. I suspect most of those rushing past don’t realise what they’re missing!

On the day we visited Queluz was virtually empty, although I suspect in high summer it has quite a few visitors. Unfortunately the peace and quiet of the garden is, in some places, disturbed by the roar of motorway traffic that runs just outside the wall on one side and the railway [luckily largely hidden in a cutting] at the opposite end of the garden. I suspect most of those rushing past don’t realise what they’re missing!

For more information about Queluz a good place to start is the official website and its on-line guide. Comparatively little research has been published on the Queluz, although there are detailed accounts of some of the restoration work on Researchgate including Conservation of the Fountains and Jose Rodrigues paper on Conservation [of] the decorative elements in the gardens, 2012. There is also a detailed analysis of the landscape by Benjamin George in Landscape Research Record No.1

You must be logged in to post a comment.