I was at Kew last week amongst hordes of people admiring the displays of cherries, magnolias and spring bulbs amongst other things. I wondered as I wandered, especially in the more popular areas around the main Victoria Gate entrance what Joseph Hooker, Kew’s Director from 1865-1885, would have made of it.

One of the great characters in botanic history Hooker was famously adamant that Kew was purely for science and not “mere pleasure or recreation seekers … whose motives are rude romping and games”.

I wondered why on earth he would think like that, so I started reading more about him, and as usual the more I read the interested I became. While I knew that he’d been plant hunting in the Himalayas [more on that in another post soon] what I didn’t realise was that he made his reputation in somewhere completely different: plant hunting in Antarctica.

I suspect a major factor behind his reluctance to widen access to Kew was because the sciences especially botany, and plant hunting, were still largely the preserve of the gentlemanly amateur. Given that professional [ie paid] scientists had low status, Kew was the main outpost of research which he wanted to preserve and enhance. There was no room for distractions such as catering to the horticultural interests of the general public. As we’ll see in the next post his experience in India was also significant.

On arrival at the Calcutta Botanic Garden in 1848 he wrote to his father that they were “more like Alger’s booth at Greenwich Fair, the Cremorne Gardens, or Baron Nathan’s Elysium at Gravesend, than a place for profit and instruction” before adding “whatever you do, never let the Pleasure ground open into the garden.” Given some of the commercial activities that Kew is currently forced to indulge in one can perhaps see his point.

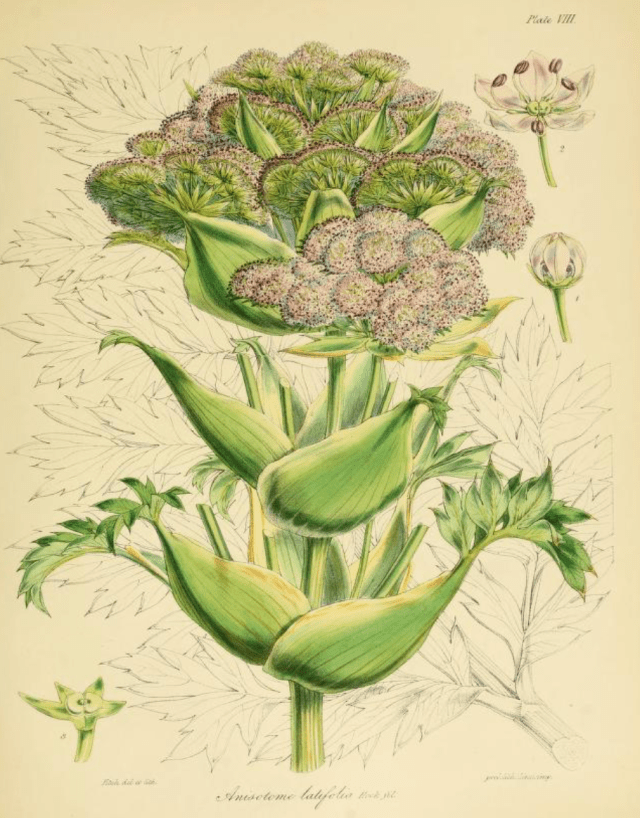

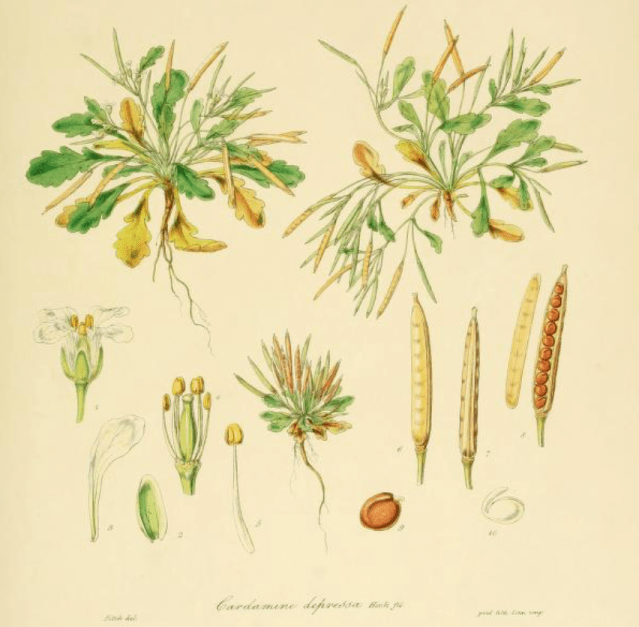

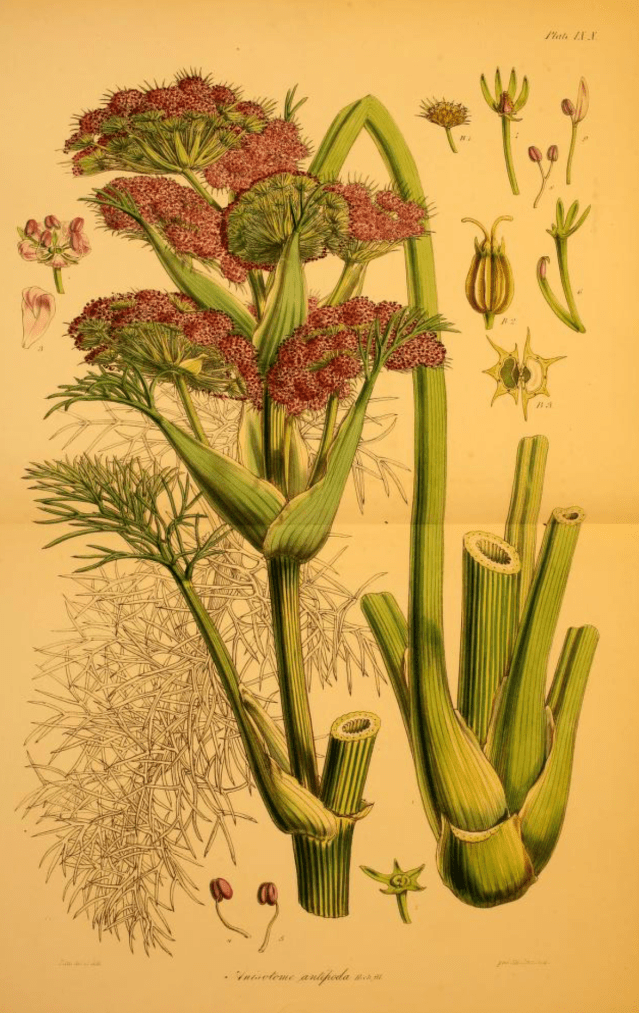

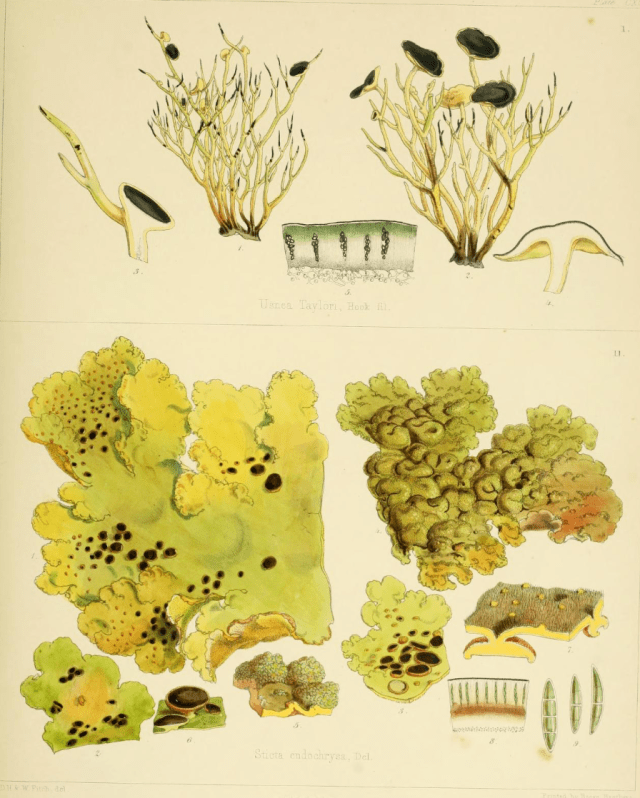

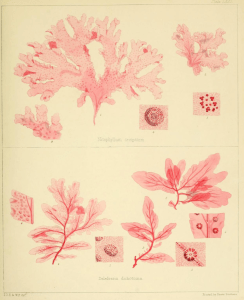

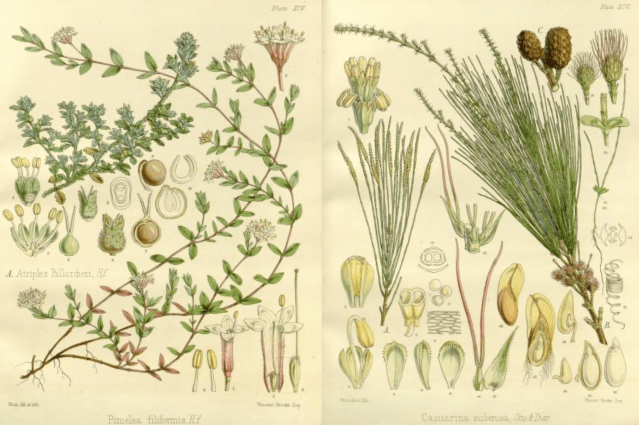

The plant images all come from Hooker’s own accounts of his voyage and how the wide range of flora – more than 3000 species in all – that he identified and recorded, from lichens and mosses to grasses, vascular plants and even seaweeds.

Born in 1817 Joseph Dalton Hooker, was the son of William Jackson Hooker, then professor of botany at Glasgow University, and his wife, Maria. His father’s job sounds impressive but at the time it was neither that high status or that well remunerated so he wasn’t born with the proverbial silver spoon in his mouth, although of course it did mean he was well connected in the scientific community.

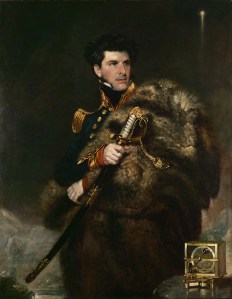

As a child he attended his father’s university botany lectures which must have given him an enthusiasm for plants. He trained in medicine, qualifying in 1839 and then looked for a career that would give him the opportunity to develop his interests in plants because there was little paid employment in botany itself. A naval career as a ship’s surgeon was the obvious choice, as naval medics had been acting as plant hunters since at least the 17th century. However, little can he have expected that soon after graduating his first posting would be quite such an eye-opening experience. It was on HMS Erebus, commanded by James Clark Ross who was being sent by the Navy to explore the southern oceans and Antarctica.

The expedition was in some ways an echo of the earlier voyage of the Beagle, with Charles Darwin on board, which had returned from a five year mission in 1836. This had a caused a sensation and Darwin had already become famous even before he published his account of the voyage. Hooker was been given the proofs to read, and was keen to follow in Darwin’s footsteps and make a name for himself.

As it happened Ross also wanted ‘such a person as Mr. Darwin‘ on board. However, even though he was a friend of William Hooker Ross didn’t feel Jospeh wasn’t in the same league as Darwin, nonetheless, after much deliberation and persuasion, at the age of 22 Joseph was finally appointed as the expedition’s botanist, doubling up the post with that of assistant ship’s surgeon.

By a twist of fate before the expedition set off Joseph was walking through central London talking to a naval officer who had sailed on the Beagle when they ran into Darwin in Trafalgar Square and so were introduced. It was an encounter that was to stand him in good stead and he took along a copy of Darwin’s journal to read on the voyage. Joseph must also have been flattered on his eventual return to get a letter from Darwin offering him specimens and asking for help classifying plants. It was the start of a lifelong friendship.

Erebus, accompanied by HMS Terror set off in September 1839, on their mission to survey the southern oceans and. investigate variations in the earth’s magnetic fields. Given how relatively easy it is now to visit the Antarctic on cruise ships it’s hard to imagine how hard such a voyage must have been. It was to be the last major expedition wholly carried out by sailing ships, with the two vessels taking over six months to reach the Cape of Good Hope. From there they overwintered on Kerguelen, one of the most isolated places on the planet. Ross carried out the first survey of the islands while Hooker and David Lyall the assistant surgeon on the Terror went botanising.Hooker named a new species of plants after Lyall as well as a Hoheria they later found in New Zealand.

From there they went to Tasmania before setting sail south to reach where Ross’s ships became the first to break through the pack-ice and reach what was to become known as the Ross Sea and the Ross Ice Shelf on the Antarctic continent.

The next winter was spent in New Zealand before in 1841 the ships set off back to Antarctica, passing round halfway the continent including overwintering in the Falklands before making their way back to Britain in 1843, having taken twice as long as anticipated.

Ross wrote a long account of the voyage , – A Voyage of Discovery and Research in the Southern and Antarctic Regions During the Years 1839–1843, – which included several long quotations taken from Joseph’s notes, while even before returning to England, extracts from letters he had sent to his father from New Zealand and Tasmania appeared in the London Journal of Botany, which his father edited. Of course Joseph had kept a journal throughout [now digitised by Kew] and wanted to write up his discoveries but was constrained by lack of money to finance the illustrations without which his findings would have been almost inaccessible to anyone other than a dedicated botanical specialist.

By this point the royal gardens at Kew had been taken into public hands and William Hooker had been appointed director, although with very little money to run them. Luckily Joseph had proved to be a talented artist, and his sketches of landscapes and plants together with his father’s influence was enough to secure a government grant of £1000 to pay for the plates in Joseph’s books. [Incidentally the same figure that Darwin had obtained for the illustrations in his account of the Beagle’s voyage] The 530 plates figured about a third of of the 3000 species Hooker described and were prepared by Kew’s principal botanic artist Walter Hood Fitch.

In all Joseph published six volumes [three two-volume titles] between 1844 and 1859, although they did not make the author any money. I suppose that’s not really that surprising as there can’t have been that much of a market for detailed dense tomes, however beautifully illustrated on the botany pf remote uninhabited – and probably uninhabitable – Antarctic islands, or even the more temperate and only recently colonised New Zealand andTasmania.

First out was Flora Antarctica, which was published in 25 sections between 1844 and 1847. It had a description of the voyage accompanied by a catalogue of the plants collected. From the text it’s clear that Hooker had a sharp and discerning eye and could work very fast under time constraints. For example in November 1840, the expedition reached Campbell Island, south of New Zealand where he managed to collect over 200 species in just two days.

On the uninhabited islands here was already some limited amount of knowledge of the flora because most had been visited before, if only briefly by other explorers. One of the best known plants already identified was the Kerguelen cabbage (Pringlea antiscorbutica), which as its Latin name indicates was used by Captain Cook as an antidote to scurvy for his crew. Because Erebus was able to spent two months on and around Kerguelen Hooker was able not only to collect seeds, but grow as many as 50 plants and plant them out in other locations for the benefit of any later visitors. He took the number of species known there from just 18 to 150, and importantly noticed that the island’s flora bore considerable similarity to that of Tierra de Fuego on the southern tip of South America.

Later in January 1843, towards the end of the voyage, Hooker landed for a short while on Cockburn Island south of the Falklands – finding only 19 different species but said “Of these nineteen plants, seven are restricted to the island in question, having been hitherto found nowhere else (besides an eighth, which is a variety of a well known species); the others grow in various parts of the globe, some being widely diffused.” How was this to be explained? Trying to answer that question he began to make comparisons between the plants he found on widely separated islands – including the Falklands, Kerguelen and the Lord Auckland Islands – and in the process discovered similarities. Exploring this further was to become a significant part of his later work.

When he returned Hooker corresponded with Darwin about it. Were these similarities simply because the plants had simply been put there by God, but if that wasn’t the case how did they arrive or get spread around? Hooker thought that perhaps the islands were merely the remains of a once much larger land mass now submerged by rising sea levels, and that “land communications” were required for the higher orders of plants to spread, although he accepted that spore-bearing forms might have been carried long distances by the “violent and prevailing westerly winds.” He thought too that cold-adapted subantarctic plants that he found isolated on New Zealand’s mountains must have been dispersed while the climate was colder than now and then been left stranded as the climate warmed. Darwin on the other hand thought it more likely that seeds had been carried between the various locations by the wind, ocean currents or birds. The two men did not come to a satisfactory conclusion and were to discuss these competing theories for years to come. In fact as I discovered while researching Hooker’s ideas that as academic journals such as the Journal of Biogeography show The debate is still continuing. [One good example is Mike Pole’s “The New Zealand Flora-Entirely Long-Distance Dispersal?” ]

Their correspondence [much of which is easily available on line – full references below] also shows that it was to Hooker that Darwin first tentatively proposed his theory of natural selection: ‘I am almost convinced‘, he wrote ‘(quite contrary to opinion I started with) that species are not (it is like confessing a murder) immutable… ‘I think I have found out (here’s presumption!) the simple way by which species become exquisitely adapted to various ends‘. Hooker suggested in reply that there might well have been ‘a gradual change of species,‘ and would “be delighted to hear how you think that this change may have taken place, as no presently conceived opinions satisfy me on the subject‘. Later when the controversy became deeper and more publicly bitter Darwin admitted Hooker was ‘the one living soul from whom I have constantly received sympathy‘ and indeed he was the first scientist to publicly defend Darwin’s ideas.

Flora Antarctica was followed by the Flora Novae-Zelandiae, 1851–3 in two volumes, one for flowering plants and the other for non-flowering ones. Flora Tasmaniae, followed between 1853 and 1860, dedicated to the local naturalists Ronald Campbell Gunn and William Archer, with Hooker noting that “this Flora of Tasmania .. owes so much to their indefatigable exertions”. It serves as a reminder that he plugged into the tiny network of botanical enthusiasts in the new colonies of Tasmania and New Zealand, several of whom were already in correspondence with his father, giving them information and even equipment which they lacked.

Such people were already a valuable part of the Kew colonial web and he was to maintain these connections for the rest of his life. The Tasmanian volumes were also the “the first published case study supporting Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection”. [For more on that see E.C.Cave’s Ph.D thesis”Flora Tasmaniae: Tasmanian naturalists and imperial botany, 1829-1860″]

They gained critical acclaim from the scientific/botanical communities. The Earl of Rosse gave an address to the Royal Society in 1854, written up in the Philosophical Transactions the following year commending Joseph’s work saying it had “at once established for you a high place as a philosophical botanist.” But it also raised a critical question of what was then known as “Geographical Botany” or “the origin”and distribution of species>’ This was particularly noticeable because of the‘The peculiar configuration of the Southern hemisphere, in which the land bears so small a proportion to the sea,” Hooker had ,said the Earl, “brought together a great number of facts relative to insular floras, which throw much light upon this point of abstract science; and in your Flora of New Zealand (now in progress), you have discussed the question in all its bearings, in an essay which has attracted much attention, from the cautious and philosophical manner in which the subject is treated.

What Hooker learned during the four-year expedition became a valuable part of his cumulative knowledge of plants worldwide and their distributions. He became, as Peter Raby his biographer said, “the outstanding English geo-botanist of the century, and his distinction was founded upon an unrivalled basis of experience on the ground”

The expedition may have earned Hooker a reputation but when it was over he had to find more employment. He ended up working as the botanist for the Geological Survey of Great Britain investigating investigation of the extinct Flora; and publishing an account of the plants of the Carboniferous Age. BUT then came another opportunity that he could not resist: a trip to the Himalayas. More on that next week

Hooker’s books on Antarctic botany can all be found at the Biodiversity Heritage Library. For more information on Hooker’s search for work and the dilemma of being a paid professional scientist rather than an unpaid but gentlemanly amateur like Darwin see Jim Endersby, “A Life More Ordinary: The Dull Life but Interesting Times of Joseph Dalton Hooker” in Journal of the History of Biology, Winter 2011.

You must be logged in to post a comment.