As we saw last week Joseph Hooker was enamoured from an early age by botany, and having returned from the Erebus expedition to the Antarctic he looked for new plant hunting opportunities.

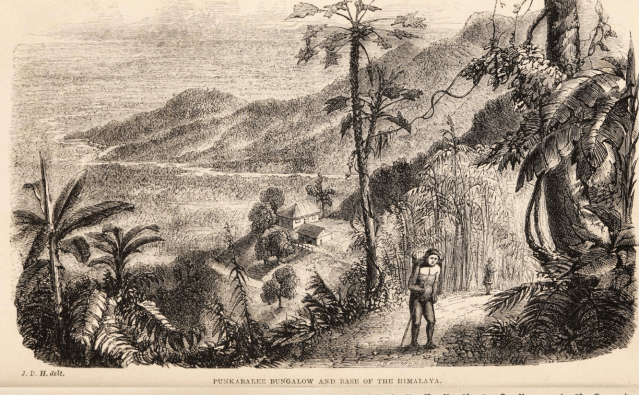

His friend Dr. Hugh Falconer, the future Director of the botanic gardens in Calcutta and later Edinburgh, recommended Sikkim as “being ground unseen by traveller or naturalist” which offered the opportunity to investigate three distinct climatic zones from tropical in the valleys, through temperate forests , to alpine and montane. The idea obviously appealed.

Afyr a lot of string-pulling the Royal Navy gave Joseph free passage on the ship taking Lord Dalhousie, the newly appointed Governor-General, to India in November 1847. It came with a grant of £400 per annum and Joseph’s task was to head to the Himalayas and go plant hunting for Kew where, of course, his father Sir William Hooker, was the director.

Little did he know he’d be locked up and need a bit of gun-boat diplomacy to return home…or that he’d start a new plant craze in British gardens

What struck me most when reading Hooker’s journal and letters back to family and friends, was what a great travelling companion he must have been: friendly, out-going, incredibly resilient and often self-deprecating. Having thought I could sum up his Himalayan adventures in a single post I think could actually fill half a dozen, but don’t worry I’m not going too. Instead I’ll write more about his other exploits in India soon, but today I’m going to try and confine myself to the various difficulties and hazards he faced in his hunt for new plants, especially rhododendrons.

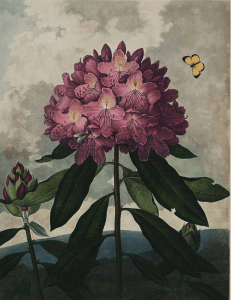

You might wonder why it was rhododendrons. Although there had been a slow trickle into western Europe from both North America and Asia, by 1800 there were only twelve species known in cultivation, and only thirty-three species by the time Joseph left for India. His father explained that “perhaps, with the exception of the Rose, the Queen of Flowers, no plants have excited a more lively interest throughout Europe than the several species of the genus Rhododendron, whether the fine evergreen foliage be considered, or the beauty and profusion of the blossoms” Joseph was to collect, sketch and describe 43 species of which 36 are still recognised as distinct.

Lord and Lady Dalhousie proved amiable enough travelling companions, and despite not being the slightest bit interested in natural history were later to be very supportive. However the journey was an adventure, and not always a good one. They arrived in Alexandria and, since it was before the Suez Canal had been dug, had to cross Egypt to reach another ship at Suez. Hooker went to see the pyramids but was almost left behind and had to chase the rest of the party on a camel. To make matters worse the ship that was to take them from Suez was not big enough for the party. This meant lesser mortals like Hooker had ” to pig it out in the ship’s armoury, a dirty place, next to the engine, intolerably hot and smothered with coal-dust.” He been collecting specimens throughout the journey but now ” lost nearly all from the salt water in our wretched dormitory… Not only were much of my collections destroyed, but my spare paper; so that at Point de Galle [in Sri Lanka] I could not collect a single thing.”

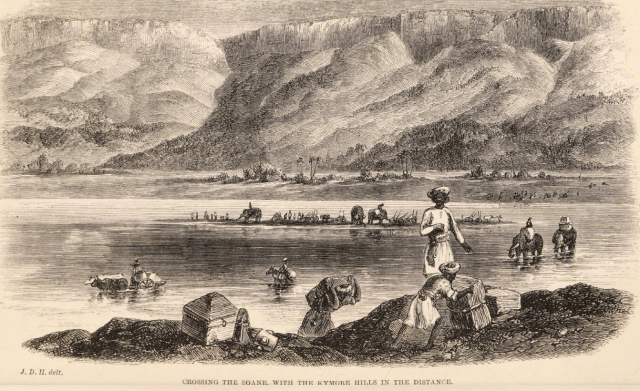

He stayed in Calcutta with the Dalhousies because immediate travel the c400 miles to Darjeeling in the foothills of the Himalayas was almost impossible because of the seasonal weather. From there he went exploring with the Geological Survey in Bengal collecting plants and anything else he thought might be useful for Kew and its promotion of economic botany. He had also become quite famous because Ross’s account of the Antarctic voyage had caused quite a stir. “You have no idea how many people in this country have been reading Ross’s work; I am better received in India for having accompanied that voyage, than ever I was on that account in England. Every individual with whom I have stayed, on my way up and down the Ganges, has read it! and knows me through it !

Eventually reaching Darjeeling he met and lodged with Brian Houghton Hodgson, the former British Resident [the nearest modern equivalent would be ambassador or envoy] in Kathmandu. The town was formerly part of Sikkim but had been leased in 1835 by the East India Company from the Rajah for use as a sanatorium, in return for an annual pension of £300, and had grown from less than a hundred people to 4,000 in the few years of British rule.

Here he also met Dr Archibald Campbell, the Superintendent of Darjeeling and the British government’s Agent in Sikkim who was to become a travelling companion for part of his trip.

Now part of India, Sikkim was then an independent kingdom, albeit small and impoverished, sandwiched in between Tibet, Nepal and Bhutan and often invaded by them. This meant its Chogyal [or King] who was referred to by the British as its Rajah, was forced to play a balancing game with them and the British regime in India and was always wary of allowing any foreigners into his country for fear of offending any of his more powerful neighbours.

Lord Dalhousie wrote to the Rajah asking for permission for Hooker to collect in Sikkim and while he was waiting for a reply Joseph went exploring in the hills around Darjeeling. The standard image we probably have of Victorian plant hunters as intrepid loners trekking along perhaps with a servant and a donkey to carry his baggage is a fairy tale. On his first trip in May 1848 he took a party of 15 servants to Mount Tonglo, 10,000ft high, on the Sikkimese border. It was only a dozen miles away as the crow flies, but thirty on foot.

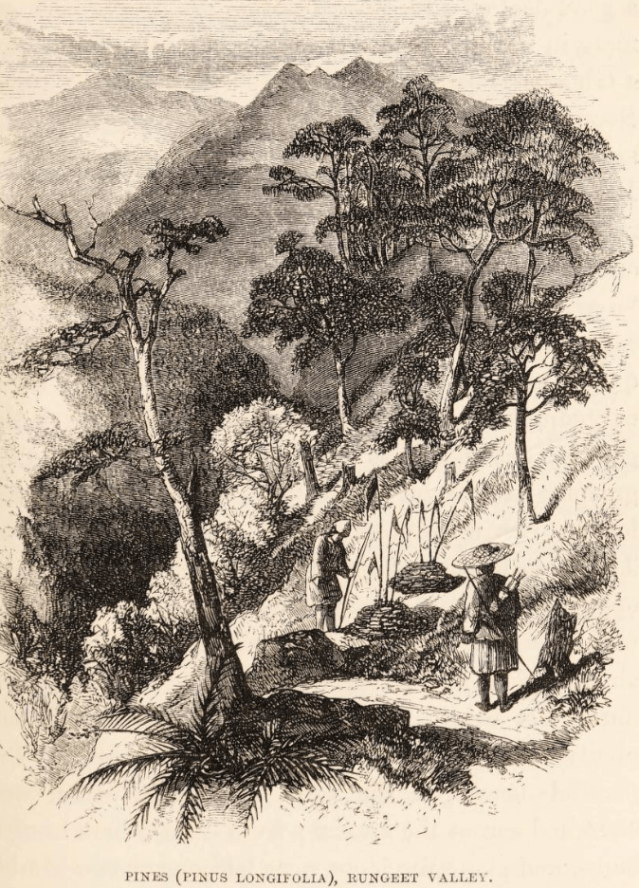

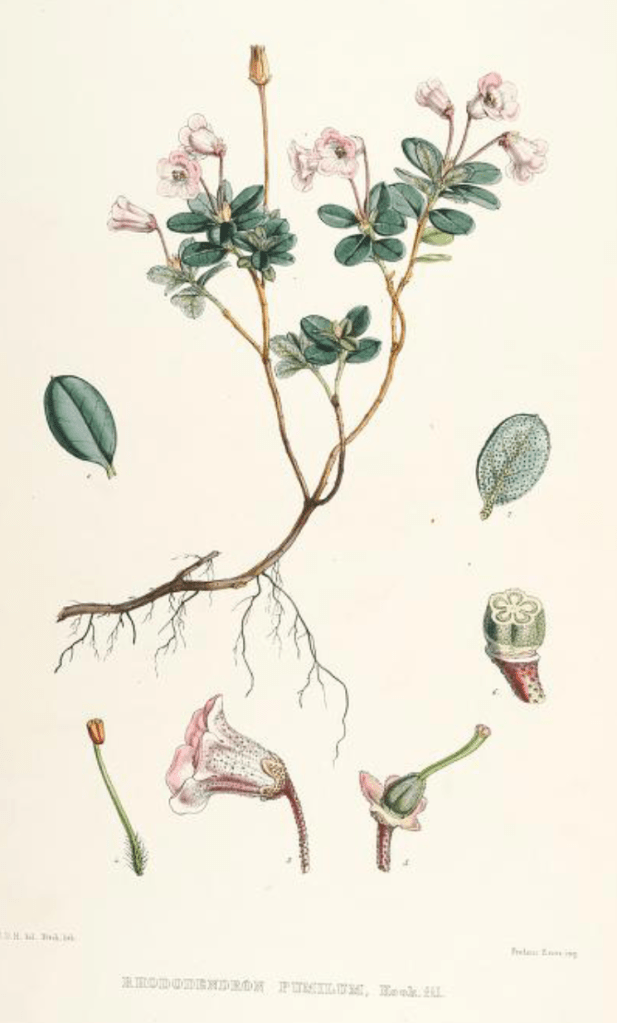

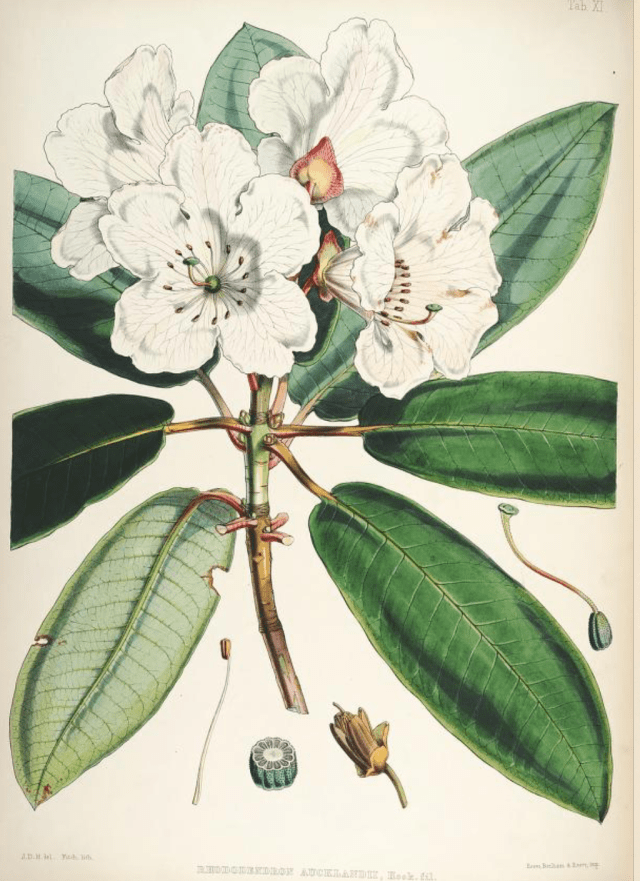

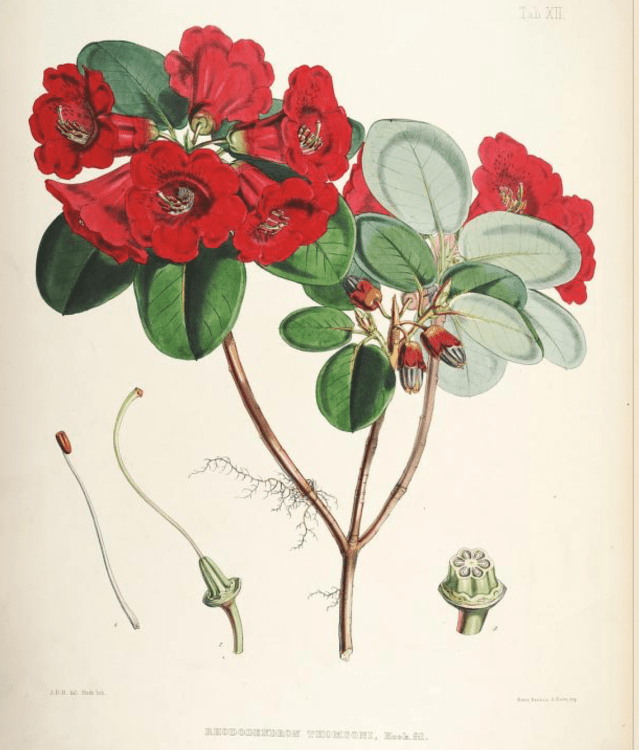

On the approaches he found a new magnolia which he named after Hodgson. and his first new rhododendron, the large-flowered sweet-smelling white one later named for Lady Dalhousie. A straggly plant up to about 8v feet high it was the only species he was to find growing as low as 7,000 feet. It was also epiphytic, “always seen growing, like the tropical Orchidee, among moss and Ferns and Aroidee, upon the trunks of large trees” [see the first image in this post]. They found the summit covered in scarlet-flowered R. Cambelliae which often reached a height of forty feet, and in a sign of his observational skills Hooker was later to observe that “the greater the elevation above the sea at which this species grows, the redder or more deeply ferruginous was the under-side of the leaf.”

The return journey was a disaster. It rained incessantly, the servants fell ill and the heavier and bulkier specimens had to be abandoned. Nevertheless what remained was he said “a glorious collection, making a pile six feet high in the drying papers. If I can only succeed in getting these glorious things to Kew, how happy I shall be.”

Of course Hooker was not collecting all these plants personally. He had a large team of locals to do the work for him and that summer he doubled their number to as many as 18, “because the plants are flowering and dying so rapidly that it takes all my energy to keep a good collection up. The papers too have all to be changed daily and dried individually over the fire — the rooms are so damp that hanging up to dry is no use. … [I am dreadfully badly off for paper, having used all that Falconer sent me up and all the newspapers )” before adding plaintively “the rain it raineth every day…” It was “a vile climate, far worse than Glasgow.”

The Rajah eventually replied refusing permission, but saying that if Hooker wished to examine the plants and animals of Sikkim, he would order suitable samples to be sent to him. Meanwhile a similar request from Dalhousie to the ruler of eastern Nepal was granted, so Hooker instead spent three months exploring and collecting there before crossing into Tibet where no westerners had been there since an East India Company embassy in 1789

Again he was not exactly alone. There were fifty-six in his party. Apart from his body-servant, he needed a man each to carry his tent and equipment , surveying instruments, bed, box of clothes, books and papers. Seven more carried papers for drying plants, and other scientific stores. The Nepalese soldiers who acted as his protection had two “coolies” of their own, while his interpreter, and “my chief plant collector (a Lepcha, the local indigenous people), had a man each. Mr. Hodgson’s bird and animal shooter, collector, and stuffer, with their ammunition and indispensables, had four more ; there were besides, three Lepcha lads to climb trees and change the plant-papers,… and the party was completed by fourteen Bhotan coolies laden with food”

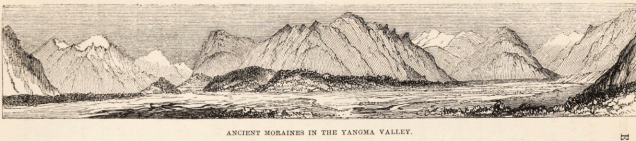

His journal describes the landscape, geology, climate and vegetation in minute detail and also includes the occasional account of the hazards: the roads were “infamously bad, generally consisting of a narrow, winding, rocky path among tangled shrubs and large boulders, brambles, nettles, and thorny bushes, often in the bed of the torrent.”

He plotted the vegetation on “a Carte Geognostique from the plains to 10,000 feet”, and continuously sending plants and specimens down to Calcutta for despatch to Kew . The supply of new material was almost endless. ‘The richness of this Flora is most remarkable and new things are brought to me every day. I dissect and sketch roughly the most important, including all the Orchideae.”

By the time of their return journey from Tibet the Rajah had changed his mind and authorised Hooker to pass through Sikkim. En route he heard from Campbell that he had negotiated a face to face meeting with the Rajah and his ministers.

It was in held in a “shed hung with faded China silk ; there was no furniture ; we brought, at the Rajah’s request, our own chairs” while “the Rajah squatted, cross-legs, a little body swathed in yellow silk, with a pink, broad-brimmed and low-crowned hat under “a shabby canopy.” Although it passed off uneventfully they were warned by the Dewan, the Rajah’s chief minister – who was, said Hooker, “the very most consummate liar and scoundrel in all political matters that you can imagine” – against further crossings into Tibet. This of course was exactly what Hooker was intending to do on a second expedition the following year. Of course it’s also true that the ministers were right to be suspicious because Hooker was not just plant collecting but surveying the country as he went and his maps were later used by the British military.

“Map of Sikkim and Eastern Nepal by J. D. Hooker, Esq., M.D.R.N, F.R.S., Shewing His Routes”

You can just make them out in red, and they show how his criss-crossed the country

His plan was to cross the eastern side of Sikkim again heading for the Tibetan passes. They set off on May 3rd 1849 with a slightly smaller party than the earlier one – a mere 42 including 10 soldiers. Travel was once again extremely difficult. There were no maps of the mountainous terrain and no proper roads, just precipitous paths that rapidly dropped and rose hundreds of feet at a time and which were constantly washed away by torrential rains or blocked by landslides. “Sometimes the jungle is so dense that you have enough to do to keep hat & spectacles in company”. Rushing streams to be crossed on rickety bamboo bridges didn’t help while fierce winds, freezing cold nights and insects all helped made life a misery . Hardly the luxury trip western tourists can take today.

There were also constant delays probably arranged by the Dewan. Local officials refused passage, roads were deliberately left unrepaired, guides took wrong turnings, food mysteriously did not appear as promised, so all in all it was it was a very testing time. He noted that “a hole in the rock or a shed of leaves is very often my residence for days, and my fare is just rice and a fowl, or kid, eggs, or what I can lay my hands on — no beer or luxuries.”

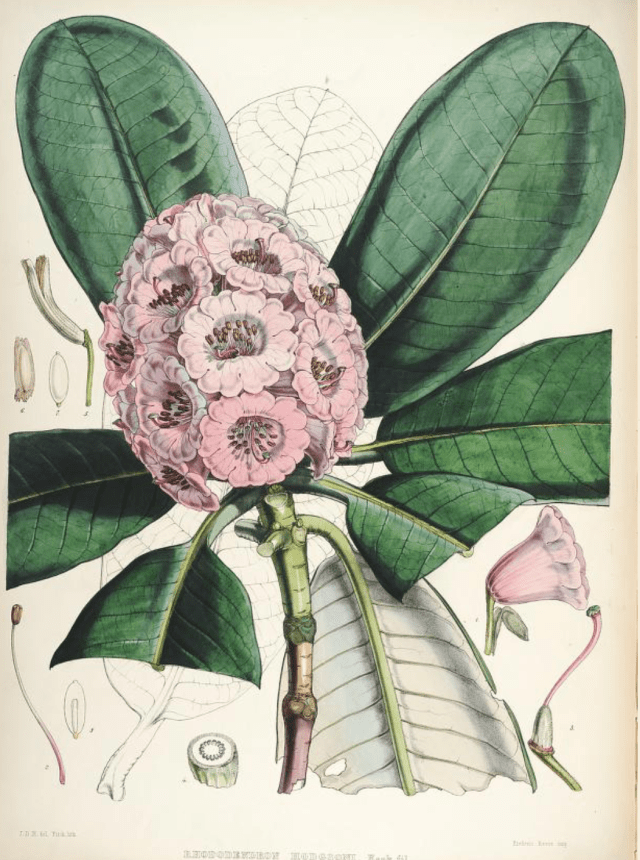

Nonetheless he went on collecting, particularly rhododendrons. There were as many as 25 new species which he noted inhabited different elevations. They included the tree-like R. Argenteum which grew best at 8-9,000 feet whilst higher than that it gave way to another tree-like species R.Falconeri.

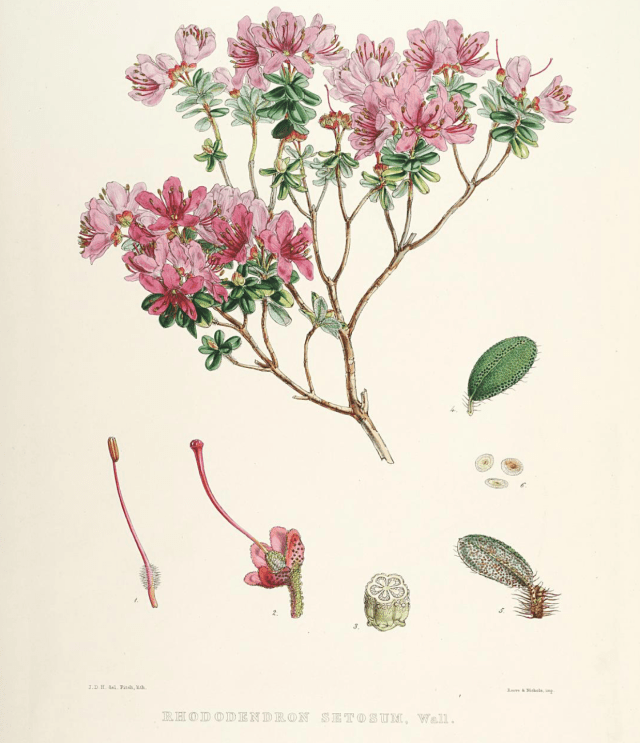

Higher still could be found R. Hodgsonii, which had an average height of 20 ft. This, Hooker said, “together with Abies Webbiana, I have always regarded as the characteristic tree and shrub (or underwood) at the elevation of 10 to 12,000 feet in all the valleys of Sikkim” before being succeeded in turn “by the arctic one of R. anthopogon, R. setosum, R. eleagnoides, and, finally, far above the ordinary limit of phanogamic vegetation, by R. nivale, which is found at an elevation of 18,000 feet above the level of the sea.”

Perhaps it’s no wonder Joseph suffered from altitude sickness!

Bad weather and the other delays meant that many of the live plants he despatched died on their way back. He wrote ruefully that”one of my finest collections of Rhododendrons sent to Darjeeling got ruined by the coolies falling ill and being detained on the road, so I have to collect the troublesome things afresh. If your shins were as bruised as mine tearing through the interminable Rhododendron scrub of 10-13,000 feet you would be as sick of the sight of these glories as I am.”

He wrote to his father that he ” had hoped to make a very fine collection of seeds on the road down here, but it sleeted and snowed all the first day, and rained tremendously all the other two, which sadly impeded my proceedings.” At another point he “brought down three loads of 80 Ibs. each of plants whose sodden state now keeps me hard at work. It is a very fine collection after all, with heaps of new and curious things from the Passes.”

Nevertheless as his published correspondence makes clear while The journey produced “wonderful results” it ended in “a very unpleasant adventure.” when, after Campbell joined Hooker, the two were overpowered by a gang of the Dewan’s men and then imprisoned. They were effectively held hostage for nearly two months while the Dewan tried to extort better terms in the treaty between Sikkim and India. Stiff upper lip prevailed as Joseph’s journal notes: “I was seized in the hope of extracting information from me (by intimidation and otherwise) as to what course these stupid people should pursue. In this, I am happy to say, they have utterly failed.”

You can find the full account of this incident in Chapter 25 of his Journal

The Dewan had made a major error of judgement and had no idea how seriously the Indian Government would regard what had happened. Messages were smuggled out and although initial polite requests for their release were ignored, when Dalhousie heard there was in instant response. Troops were immediately sent to Darjeeling and headed towards Sikkim while an ultimatum given to the Rajah which could not be ignored. The Dewan himself was forced to lead the party of now ex-prisoners back to Darjeeling, although as Hooker said it was “as slowly as he could contrive to crawl.” They finally reached the town on Christmas day 1849. As a reprisal the Rajah lost his pension and 640 sq miles of southern Sikkim was annexed by the British government.

Hooker now set to work pressing the plants and flowers he and his collectors had found, sketching specimens, bottling beetles and generally recording in scrupulous detail everything that had been gathered before sending 80 separate loads down to Calcutta to be forwarded to Kew, including live plants in Wardian cases. His work was to lead to one of the greatest of those magnificent Victorian coffee-table books Rhododendrons of the Sikkim-Himalaya , which was edited by his father and lavishly illustrated by Walter Hood Fitch who redrew Joseph’s sketches for publication. The first part with 10 species was published in 1849 when Jospeh was still in India, the second and third parts with another 21 species appeared in 1851.

Seeds sent to Kew were successfully propagated and soon entered the commercial nursery world. It led to a rhododendron craze in Britain with several great estates trying to recreate Himalayan landscapes. Hooker himself visited Cragside in Northumberland describing it as a beautiful ‘wilderness’ rather than a garden but comparing it to the rhododendron regions he had explored. At Menabilly in Cornwall a valley garden known as Hooker’s Grove was laid out with ornamental trees and conifers underplanted with rhododendrons, while at nearby Heligan Kew also supplied rhododendron seeds from Hooker’s expedition. Others who received seeds or plants included Charles Darwin at Down House, Florence Nightingale’s father who grew several of the species sent by Hooker in their garden at Embley Park in Hampshire, and Sandling Park where a specialist collection of rhododendrons and azaleas, was begun in 1845, with plants again coming from Hooker.

And, of course, Hooker’s rhododendrons were cultivated at Kew and used to reinvigorate the Rhododendron Dell, originally landscaped by Capability Brown. Some of the original planting still survives so make sure you get down to see them in flower next month!

Apart from the published texts linked above the best place to start looking for more information is the Kew’s website and in particular its Joseph Hooker Correspondence Project which has transcriptions and digital images of his letters in their archive.

The Rhododendron Dell at Kew. Photo by Andrew McRobb RGB/Kew

You must be logged in to post a comment.