Easter is always a difficult time for garden-related bloggers – there’s only a limited and rather obvious range of possibilities – bunnies, chocolate, easter lilies, ,passion flowers, chickens and eggs and over the last 12 years I’ve done most of them. Then I remembered a lovely story in a lecture I give about one of the nicest people in garden history that took place one Easter.

We know gardening appeals to a very wide range of people but is it a classless pursuit? Is there any real connection between the wealthy and their ability to garden on a grand scale: think paid staff, stately homes, Gardens Illustrated and Chelsea…and the rest of us, constrained for space, time and money: think suburban back gardens, Gardener’s World and the local garden centre?

Perhaps not as much as we might like and one person who definitely thought there ought to be more, was the Rev. Samuel Reynolds Hole, Canon of Lincoln, later Dean of Rochester and a great rose enthusiast. His sympathies are clear: “Not a soupçon of sympathy can I ever feel for the discomfiture of those Rose-growers who trust in riches .”

Read on to find out why….and to hear about the surprising people he thought were the real gardeners.

Canon Hole published A Book about Roses in 1896. It’s written in a light conversational style, but even so, late Victorian light conversation was rather circumlocutional, so I am taking liberties in further shortening his brief chapter: “Causes of Success.” In it he tells how he first came to realise that a love of gardening – and especially of roses – has little to do with money or class, and the powerful effect that discovery had on him.

Canon Hole published A Book about Roses in 1896. It’s written in a light conversational style, but even so, late Victorian light conversation was rather circumlocutional, so I am taking liberties in further shortening his brief chapter: “Causes of Success.” In it he tells how he first came to realise that a love of gardening – and especially of roses – has little to do with money or class, and the powerful effect that discovery had on him.

At the end of one cold and miserable March he “received a note from a Nottingham mechanic, inviting me to assist in a judicial capacity at an exhibition of roses, given by working men, which was to be held on Easter Monday.”

Hole had no roses in flower then, nor did any of his gardening acquaintances, nor did he expect any by Easter so “I threw down the letter on my first impulse as a hoax.” However, “upon the second inspection I was so impressed by a look and tone of genuine reality that I wrote ultimately to the address indicated, asking somewhat sarcastically and incredulously, as being a shrewd superior person … what sort of roses were so kind as to bloom during the month of April at Nottingham, and nowhere else. By return of post I was informed, with some much more courtesy than I had any claim to, that the roses in question are grown under glass – where and how, the growers would be delighted to show me, if I would oblige them with my company.”

So on Easter Monday, a “raw and gusty day”, he went to Nottingham and was met at the General Cathcart Inn by the landlord, “with a smile on his face and with a Senateur Vaisse in his coat, which glowed amid the gloom like a red light on a midnight train”. Inside he met “a crowd of other exhibitors, some with roses in their coats.. and some without, for the valid reason they were there in their shirt sleeves… just as you would see them at their daily work, and some of them only spared from it to cut and stage their flowers.” He was “welcomed with outstretched hands, and [they] seemed amused when, on the apologising for their soiled appearance, I assured them of my vivid affection for all kinds of Floricultural dirt… I counted no man worthy of the name of Gardener whose skin was always white and clean.”

The General Cathcart has been demolished and as far as I can see there are no photos of it, even on this amazing gallery of St Ann’s long-lost pubs

When the “roses were ready” Hole was escorted upstairs to the assembly room and found it “empty, hushed and still” and the large pine table “covered from end to end with beautiful and fragrant Roses…The bottles, which, once filled with creamy stout and with the fizzing beer of ginger, now, like converted drunkards, were teetotally devoted to pure water, and in that water stood the Rose.”

“A pretty sight, a more complete surprise of beauty, could not have presented itself on that cold and cloudy morning; and in no Royal Palace, no museum of rarities, no marked of gems, was there that day in all the world a table so fairly dight.”

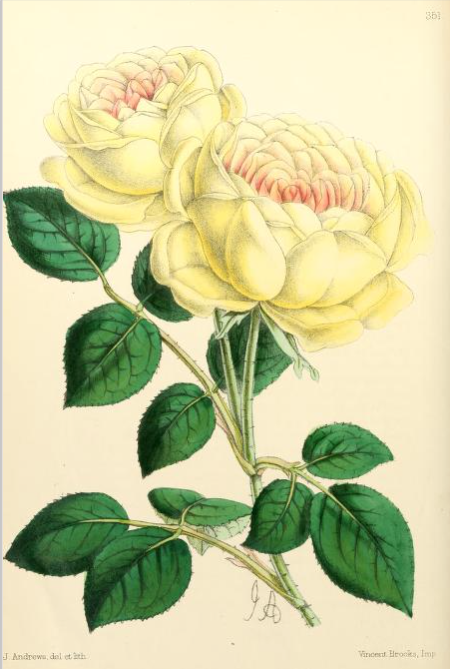

“I have never seen better specimens grown under glass, than those which were exhibited by these workingmen. Their tea roses…were shown in their most exquisite beauty; and… I do not hesitate to say that the best Marechal Niel and the best Madame Margottin which I have yet seen, appeared at Nottingham in the ginger beer bottles!… Many of the Hybrid perpetuals were shown in their integrity…and one of them, Alphonse Karr, I neer met with afterwards of the same size and excellence.”

[There were at least 4 roses named after Karr but none of them, like Madame Margottin [the first image in this post] , appear to be in modern cultivation or have any images. Karr was an author and rosarian best known today for the quote below]

“When the prizes were awarded… I went with some of them to inspect their gardens. These are tiny allotments on sunny slopes, just out of the town of Nottingham, separated by hedges or boards, in size about 3 to the rood -such an extent as a country squire in Lilliput might be expected to devote to horticulture.”

The Nottinghamshire Guardian of 8th March 1867 claimed “no town in England displays the gardening spirit more manifestly than old Nottingham. Independently of gardens attached to residences, there are, we believe, nearly 10,000 allotments within a short distance of town; and as many of these are divided, and in some cases subdivided, it is not too much to affirm that from 20,000 to 30,000 of the inhabitants, or nearly one half, take an active interest in the garden. And where will you see such Roses as produced upon the Hunger Hills by these matters… Such cabbages and lettuce, rhubarb and celery?”

Hungerhill Gardens, St Ann’s, undated mid-19thc

The Hungerhills [probably from Old English for hillside of clay] had been used as gardens from at least 1605 when there are records showing that Nottingham Corporation leased two or three acre plots to 30 Burgesses or Freemen of the town. Known as Burgess Parts by 1832 they had been subdivided into as many as 400 separate gardens, although they were still used mainly by the wealthier citizens of the city.

But with the rapid industrialisation of Nottingham and the consequent demographic boom – from about 11,000 in 1750 to 50,000 by 1831 – there was a slow transition from gardens that were used by the middle classes for recreation to allotment gardens for poorer workers. They offered a good opportunity to supplement low wages by growing their own fruit and vegetables.

In 1835 the writer William Howitt wrote an article arguing that the allotments were one of what he called the “Stepping Stones in our Progress to the Great Christian Republic“.He explained that many of these allotmenteers had “excellent summerhouses and there they delight to go, and smoke a solitary pipe, as they look over the smiling face of their garden, or take a quiet stroll amongst their flowers; or to take a pipe with a friend; or to spend a Sunday afternoon, or a summer evening, with their families. The amount of enjoyment which these gardens afford to a great number of families, is not easy to be calculated – and then the health and improved taste!” And of course it had moral virtues too: “think of the alehouse, the drinking, noisy, politics-bawling alehouse, where a great many of those very men would most probably be, if they had not this attraction to think of this…-what a contrast !-what a most gratifying contrast !” He then went on to advocate that Nottingham’s example should be emulated by every other “great town”

I’m sure that both Howitt and Canon Hole would have been impressed to learn that the 75 acres of Hungerhills, now known as the St Ann’s Allotments are now listed Grade 2* on the Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in England, as the oldest and largest group of detached town gardens in Britain.

Nowadays there’s a community orchard and a heritage plant nursery, where rare historical plants are propagated and protected, including 120 species of apple and 50 varieties of pear. The site is also amazingly biodiverse being home to more than 59 species of bird, 104 types of moths, 18 species of butterfly and 222 different plant species.

Recent years have seen them being visited by Monty Don, and BBC Gardeners’ World.[you’ll need to scroll down quite a long way to find the clip] Unfortunately their future is a bit up in the air at the moment after the Renewal Trust which has managed the gardens since 2008 and overseen a £4.5 million restoration and conservation programme, said that reduced funding levels were “too hard to overcome.” From January this year the site has been handed back to the City Council. [More about that on the Renewal trust website, and this article in the Nottingham Post]

Follow this link for lots of lovely old family photographs of the gardens together with more information about some of the characters who looked after them

Certainly the Canon was particularly impressed by the glasshouses he saw there. “Houses! Why, a full-sized giant would have taken them up like a hand-glass” and being famously tall at 6ft 7″ was unable in most of them to stand upright, and into some, to enter at all. “That ‘bit o’ glass’ had been, nevertheless, as much a dream, and hope, and happiness to its owner as the Crystal Palace was to Paxton.”

On his way home Hole noticed a timber yard which displayed “a neat miniature greenhouse” and a sign offering them for sale for 5 guineas. “How many true but poor florist has stopped to read, and sigh.” But I believe “that many a poor but brave florist has stopped to read, and has gone home to save – has come, and seen, and conquered.…”

“I could hardly believe that the grand roses which we had just left could have come, like some village beauty out of her cottage dwelling, from such mean and lowly homes. But there were the plants and there were the proprietors,…”

He asked…”How was it done?… From the true love of the Rose.”

“How do you afford to buy these new and expensive varieties?” because “I would that every employer, that everyone who cares for the labouring poor, would remember the answer, reflect and act upon it. “I’ll tell you he said how I managed to buy’ em… By keeping away from the beer shops!”

That of course was probably true but it is also the case that to afford the rent of the allotment some plot holders cultivated flowers, especially roses, for sale, which were sent in large quantities to market in Manchester and Liverpool.

“From a lady who lives near Nottingham, and who goes much among the poorer classes, I heard more of such striking instances… Conversing with the wife of a mechanic during the coldest period of a recent winter, she observed that the parental bed appeared to be insufficiently clothed, and she enquired if there were no more blankets in the house.

Yes ma’am, we’ve another but what? asked the lady. It is not at home ma’am.. Surely it’s not in pawn? Oh dear no ma’am; Tom has only just took it.

Took it where? Please ma’am, he took it… Took it… Took it to keep the frost out of the greenhouse; and please ma’am, we don’t want it, we’re quite hot in bed.”

Hole thought that Tom and his wife “ought to be presented with a golden warming pan, set with brilliants, and filled with £50 Bank of England notes.”

At the end of the day Hole “took leave of the brotherhood … delighted with their gardens, and delighted with them, but not much delighted with myself.

On reflection he felt he had “been presiding like the Lord Chief Justice in court, whereas in fact, “had merit regulated the appointment, I should probably have discharged the duties of Usher.” He was given a glorious bouquet of roses with their “best respects to the Missis” and felt ashamed how little he has done and, “how much more such men would do, with my larger leisure and more abundant means.”

When friends saw the roses he had been given, “one of my neighbours, who I knew had glass by the acre and gardeners in troops” said , that “they were the first roses yet seen this year,” and “when I explained, in all truthfulness that they came ‘chiefly from bricklayers’ there was “an expressive sneer of unbelief… And a solemn silence ensued….which said plainly … ‘we don’t see any wit in lies’.” You can almost sense the good canon’s discomfort as he “collapsed at once into my corner…looking I fear, very like the Beast when he first showed himself among the Roses to Beauty.”

The Nottingham mechanics were equally successful with other aspects of gardening and Canon Hole went on regularly to judge the annual exhibition of “St Anne Amateur Floral and Horticultural Society” which consisted largely of “Artisans occupying garden allotments in the suburbs of Nottingham,” and which “justly prides itself on having developed a taste for gardening among the working classes.”

This of course is all in the Victorian spirit of moral improvement, but Samuel Reynolds Hole seems genuinely moved by his experience and to honestly believe “that the happiness of mankind may be increased by encouraging that love of a garden that love of the beautiful which is innate in us all.”

For more information good places to start are the St Anne’s website , and the facebook page of the Renewal Trust restoration project, and this video by local historian Mo Cooper.

You must be logged in to post a comment.