I made dinner for a friend the other day, pasta with a nice mushroom sauce, but was a bit puzzled when he looked and said “I don’t really like mushrooms. There’s just something about them that freaks me out. I mean how do you know they’re safe to eat?” He’s definitely a mycetophobe!

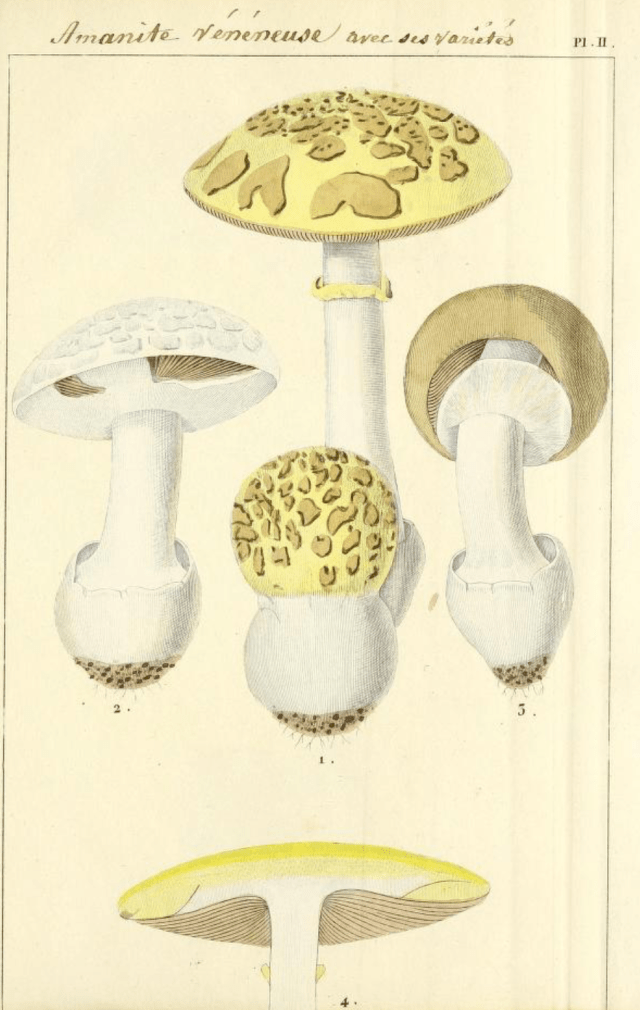

It led me to wonder where this uncertainty came from. Was that because of an irrational but inbuilt fear rooted in traditional stories about the dangers of eating fungi. Certainly , like most people, I’ve always been wary of picking them when I find them in my own garden because although most fruiting fungi are actually safe to eat, we all know that eating one of the few wrong kinds can cause hallucinations, illness or even death.

It then made me ponder about when we started cultivating mushrooms in the garden, and perhaps even more basically when did we start eating them and becoming mycetophiles?

19 species of Edible fungi: Coloured lithograph by A. Cornillon, ca. 1827, after Prieur.

image courtesy of Wellcome Library, London | CC BY 4.0

I was then a bit surprised to discover that mushrooms only begin to appear in gardening and cookery books from the mid-17thc onwards and its not until the turn of the 18th/19thc centuries when gardeners begin to take their cultivation seriously

Before that there seems to have been a clear revulsion against eating things which were thought to grow out of what James Hart, an early 17th century doctor in his book Klinikē, or The diet of the diseased (1633), called “the excrements of the Earth, the slime and scum of the water, the superfluity of the woods and to putrefaction of the sea: to wit… Frogs, snails, mushrooms and oysters.”

Others followed in the same vein. In his book “A Watchman for the Pest” Stephen Bradwell likewise observed that “Some have from strangers (ie foreigners) taken up a foolish tricke of eating Mushroms or Toadstooles.”

Bradwell’s advice to would-be mushroom-eaters was unequivocal: “let them now be warned to cast them away; for the best Authors hold the best of them at all times in a degree venomous.”

Mind you his list of foods to be avoided was impressively long – summer fruit, beans, peas, garlic, water fowl, freshwater fish, milk, cream, shellfish, cabbages, rocket, lettuce etc etc . There wasn’t much left if you really wanted to avoid being ill!

As Keith Thomas in his insightful book Man and the Natural World pointed out [p.54-55] it doesn’t help that fungi tend to appear suddenly, to flourish in damp dark places such as rotting wood or other vegetation, and manure heaps. Much was made of the fact that they grew in dark, moist places, and they were thought to be engendered by decaying vegetable matter: Bradwell viewed them as “a bundle of putrefaction, arising of a cold, moist, viscous matter of the Earth.” Of course that didn’t mean that everyone took this medical advice because clearly some people were eating them although as Hart’s contemporary the physician Tobias Venner declared it was only those who were “phantasticall ” who “doe greatly delight to eat of the earthly excrescences called Mushrums”.

At the same time as they ere seen as unwholesome they were also baffling. This was the time when early botanists were trying to impose more standard classifications on the natural world. Fungi caused them a few headaches. They didn’t seem to fit anywhere logical. Were they even part of the vegetable kingdom? The early 17thc Swiss botanist Gaspard Bauhin suggested “mushrooms are neither plants, nor roots, flowers, or seeds, but only humidity coming from the soil, the trees, dead wood and other rotten elements” whilst James Hart said they were “commonly ranked” among vegetables even though “properly they be no roots”. So where should they go in an encyclopaedic work like John Gerard’s Herball of 1597.

The answer was mushrooms and toadstools were placed in the last third and last part of the book, with the odds and ends of the vegetable world such mosses, sundews, liverworts, corals and sponges, and a few exotics like cloves and nutmeg. The only things that come after fungi in this rag-bag miscellany are petrified wood and the imaginary barnacle goose. This dilemma persisted right through until the serious study of fungi – now known as mycology – began slowly to emerge in the later 17thc with the development of the microscope.

For a detailed account of how early botanists attempted to classify fungi and account for their growth etc seeThe drawings of Mushrooms by Claude Aubriet by Xavier Carteret and Aline Hamonou-Mahieu

from The New Student’s Reference Work (1914)

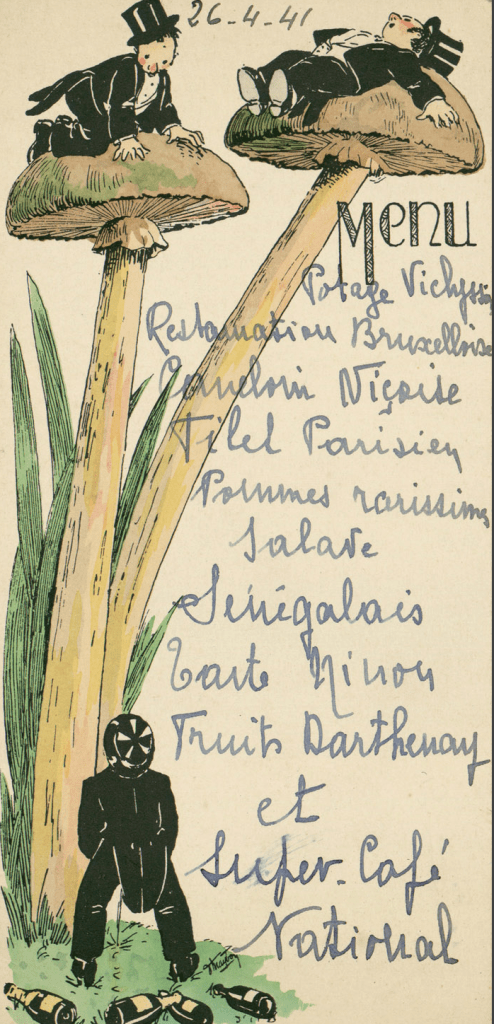

Mushrooms don’t really feature in British cookery books before the Restoration but the forced exile to the continent of many royalist members of the elite during the Civil War began to change things. That’s probably because the French and Italians didn’t seem to have as many hang-ups abut eating fungi as the Brits did. The royalist exile Sir Kenelm Digby published his cookery book : The Closet Opened in 1669 which included recipes with mushrooms. Telling his reader that “Champignons are best, that grow upon gravelly dry rising Grounds.” he advises that to make pickled mushrooms they be boiled and ‘scummed’ Mind you he was viewed as decadent with one Puritan commentator comparing his own lifestyle with Digby’s as much the same as the difference “between solid wholesome meats, and a dish of frogs or mushrooms made savoury with French sauce.”

Mushrooms don’t really feature in British cookery books before the Restoration but the forced exile to the continent of many royalist members of the elite during the Civil War began to change things. That’s probably because the French and Italians didn’t seem to have as many hang-ups abut eating fungi as the Brits did. The royalist exile Sir Kenelm Digby published his cookery book : The Closet Opened in 1669 which included recipes with mushrooms. Telling his reader that “Champignons are best, that grow upon gravelly dry rising Grounds.” he advises that to make pickled mushrooms they be boiled and ‘scummed’ Mind you he was viewed as decadent with one Puritan commentator comparing his own lifestyle with Digby’s as much the same as the difference “between solid wholesome meats, and a dish of frogs or mushrooms made savoury with French sauce.”

It was in France that deliberate mushroom cultivation seems to have started in Europe. They were grown outside in the kitchen gardens at Versailles by Jean de la Quintinie, gardener to Louis XIV in the late 17thc. The English scientist Martin Lister saw them being forced commercially on a visit to Paris in 1698: “But after all, the French delight in nothing so much as Mushroomes ; of which they have daily, and all the Winter long, store of fresh and new gathered in the Markets. This surprised me ; nor could I guess where they had them, till I found they raised them on hot Beds in their Gardens. Of Forc’t Mushroomes they have many Crops in a year ; but for the Months of August, September, October, when they naturally grow in the Fields, they prepare no Artificial Beds.”

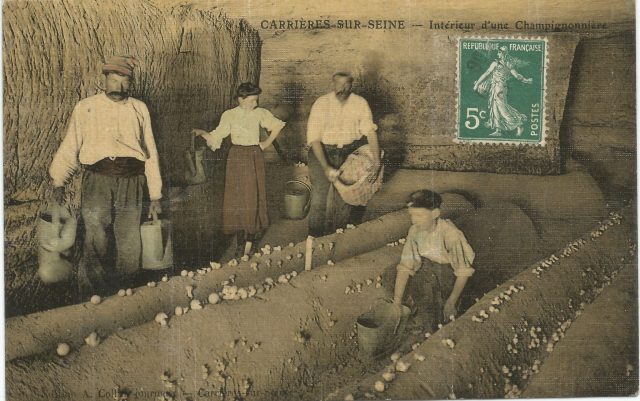

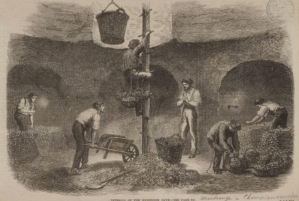

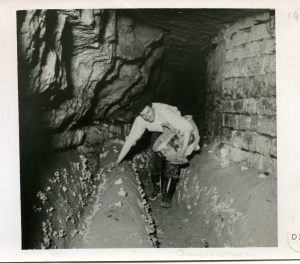

The next big development took place during the Napoleonic wars when the story goes that a farmer in the Paris suburb of Passy chucked a disappointing crop of mushrooms and the compost he had grown them in down into a disused limestone quarry. He later discovered a really worthwhile crop had grown there and so attempted to cultivate more in the semi-darkness. It wasn’t long before he realised that some species grow better underground than on the forest floor, and by cultivating them in the dark with comparatively stable climatic conditions he could turn them into a year-round crop.

From the disused quarries around Paris, attention then turned to using the extensive network of catacombs that run under Paris itself and by 1880 more than 300 farmers were growing fungi underground producing an annual harvest of 1,000 tons, with the crop doubling over the next 20 years. Hence why in France the “standard” white mushrooms are known as champignons de Paris. As Paris expanded production shifted to the limestone and tufa areas of Loire valley, although there are still just a couple of growers still using the tunnels, and one major new venture to revitalise the industry, albeit on a small scale.

For more on the Paris catacombs and mushroom growing there see this post on the Atlas Obscura website

In Britain the earliest comments I can find suggest that mushrooms were grown in beds in the open garden. This was described in the first specialist book I can find on cultivating mushroom by the prolific garden writer JohnAbercrombie published in 1779. Its full length title The garden mushroom : its nature and cultivation : a treatise exhibiting full and plain directions, for producing this desirable plant in perfection and plenty, according to the true successful practice of the London gardeners implies that mushrooms were already being widely grown by market gardeners. He explains that “about London, great quantities of Mushrooms are raised for the markets, and consequently vast supplies of spawn are annually required. There are experienced Mushroom-men, who, at the proper season, go about collecting, both in town and country, the true sort, which they buy commonly from about half a crown to five or six shillings per bushel,..Good spawn may also be purchased occasionally of the kitchen-gardeners in the neighbourhood of London, many of whom have extensive Mushroom-beds, as well as common hot-beds.” These beds are filled with horse dung – for private use one 15ft long is prob enough..But for the supply of the London markets, long parallel ranges are made, from twenty to fifty feet in length.”

In Britain the earliest comments I can find suggest that mushrooms were grown in beds in the open garden. This was described in the first specialist book I can find on cultivating mushroom by the prolific garden writer JohnAbercrombie published in 1779. Its full length title The garden mushroom : its nature and cultivation : a treatise exhibiting full and plain directions, for producing this desirable plant in perfection and plenty, according to the true successful practice of the London gardeners implies that mushrooms were already being widely grown by market gardeners. He explains that “about London, great quantities of Mushrooms are raised for the markets, and consequently vast supplies of spawn are annually required. There are experienced Mushroom-men, who, at the proper season, go about collecting, both in town and country, the true sort, which they buy commonly from about half a crown to five or six shillings per bushel,..Good spawn may also be purchased occasionally of the kitchen-gardeners in the neighbourhood of London, many of whom have extensive Mushroom-beds, as well as common hot-beds.” These beds are filled with horse dung – for private use one 15ft long is prob enough..But for the supply of the London markets, long parallel ranges are made, from twenty to fifty feet in length.”

Alongside this interest in deliberately growing mushrooms rather than merely gathering them was a growing scientific interest, with the first book on the subject of fungi came out in 1729. Nova plantarum genera was written by Pier Antonio Micheli the botanist and gardener to Cosimo III de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany. It has descriptions of 1900 “plants”, including as many as 900 different fungi and lichens, arranged systematically.

He also discovered how fungi reproduce by means of spores and was the first to deliberately to culture molds by placing some of them on freshly cut bits of fruit.

Micheli was well in advance of his ti.me and its not until much later that the German/Dutch botanist Christiaan Hendrik Persoon(1761–1836) building on Micheli and Linnaeus established a more accurate scientific classification in his book on edible mushrooms of 1818.

There was clearly a widening of interest across Europe because around the same time other books about fungi were being published in French, German and Italian while James Sowerby was leading the way in Britain with his Coloured figures of English fungi or mushrooms published in sections between 1797 and 1809.

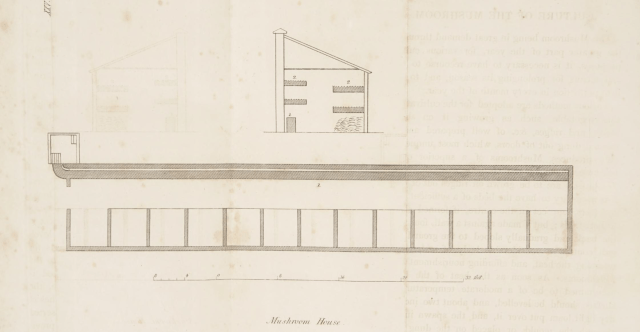

The combination of improved horticultural expertise and greater culinary interest led to the development of the specialist mushroom house. This was not a very complicated structure and generally took the form of a windowless shed with stacked and divided shelves , often on the north-facing outside wall of a walled garden.

The first description I have found is in Dickson and Edwards’ A Complete Dictionary of Practical Gardening 1807 which also includes this basic plan and cross-section. The idea was ” recommended by the author of the Scotch Forcing Gardener, who has found it well adapted to the purpose.” This is rather strange because the author was James Graham Temple and his book wasn’t published until 1828, and I can find no trace of an earlier edition, while the Dictionary was definitely published in 1807. Any suggestions welcome!

The first actual example I found was, perhaps not surprisingly, at Spring Grove House, the estate of Sir Joseph Banks, who was effectively running the royal gardens at Kew. The house, which has a heating system and flue, to allow for all-year-round production, was devised by Sir Joseph’s gardener, Isaac Oldacre [sometimes Oldaker] who had formerly worked for the Tsar of Russia and who based it on designs he had seen in Germany. It is mentioned in the Transaction of the Horticultural Society 1816 and also by Patrick Neil in his Journal of a horticultural tour..in 1817 . Oldacre’s own lengthy description can also be found, along with the sketch above, in Loudon’s Encyclopaedia of Gardening

Another heated mushroom house, this time thatched, was described briefly in James McPhail’s The gardener’s remembrancer. of 1819 and by 1822 at the latest there was a mushroom house at Kensington Palace.

A flurry of books including several by John Claudius Loudon and Henry Philips all pick up on the idea and within a decade the mushroom house had become a must-have feature of the country house estate. Soon general Gardeners Kalendars and instruction manuals such as the 1831 A guide to the orchard and fruit garden by George & John Lindley are listing the tasks that needed to be carrying out each month in the mushroom house. The 1833 Hortus Woburnensis, which describes the Duke of Bedford’s gardens takes things one stage further because Mushrooms now “being in great demand throughout the greater part of the year, for various culinary purposes, it is necessary to have recourse to artificial means for prolonging its season, and to bring it to perfection in every month of the year.” The fact that the house had to be heated meant that it was now usable for forcing other crops – such as rhubarb, chicory, seakale and asparagus which required warmth in the winter season but crucially did not need light.

I’m not going to try and list. all the houses I’ve seen mentioned, partly because very few images are available since mushroom houses are not particularly photogenic but I will just mention a few other early examples. These include Alnwick Castle where the 2nd Duke of Northumberland invested in new hothouses, two vineries, a mushroom house and a fruiting pine stove which were built between 1808 and 1811. Sir Charles Monck at Belsay in Northumberland was not far behind. When he rebuilt the house between 1810 and 1817 he also created a new kitchen garden alongside the estate’s formal gardens. This had a heated wall and a range of hothouses for growing exotic fruit, but it also specifically included a mushroom house.

The crop at Christmas 2024 in the mushroom house at Audley End

At least two working examples survive. One is at Audley End where the walled kitchen garden contains an 1820 vinery range and back sheds comprising bothy, potting sheds, tool sheds, and mushroom house. What’s especially nice about this examples that its back in use as ` productive space as the head gardener explains on her Instagram account. A later mushroom house at Hanbury Hall in Worcestershire is also is still productive with the produce going to the tearoom there.

These days as the website of the Mushroom Council shows, the range of what is easily available both to eat and to grow is much greater than it was in the 19th century. If you don’t have room for a mushroom house of your own but you fancy growing some there are plenty of website and YouTube videos to get you going.But don’t be like me, who failed miserably, and instead remember the advice of head gardener Mr Kennedy-Bell who pointed out in an article in Garden Life in 1911 that “Mushrooms can be successfully grown in any shed or outbuilding, if the preliminary details are attended to, but the secret of success lies in rigid attention to these small details.”

Good luck!

You must be logged in to post a comment.