This post isn’t going to try and convince you to change your mind but instead follow up on last week’ post and look at the apparent link between magic and mushrooms and fairies and fungi.

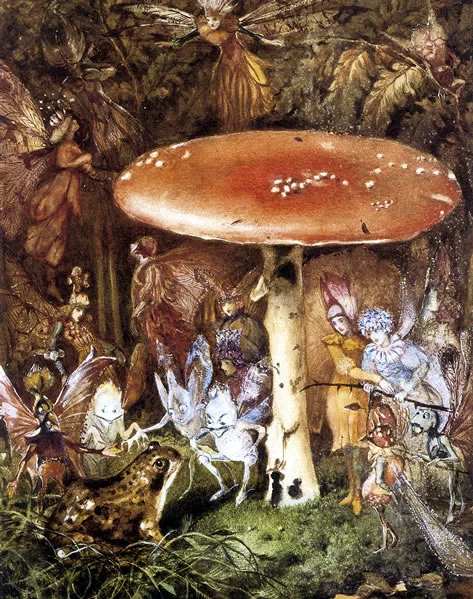

As many of you will know I’ve lectured widely in the history of garden gnomes and one of the things that struck when i was researching for that was how many mushrooms and toadstools appeared in images of them and other “little folk”, whether in fairy stories or paintings. But why?

I wonder if it’s anything to do with the properties of certain mushrooms? So off we go down another research rabbit-hole.

Perhaps the most common of all these links between fungi and fairies concerns the circles or arcs of mushrooms known as fairy rings. Theories about them, their origins and meaning vary between cultures but that link with the supernatural is always there. Did they mark areas where fairies might be seen, or perhaps where an unwary visitor could enter the fairy domain? On the plus side, in some accounts entering a fairy ring on the night of a full moon was supposed to bring good luck – but generally it’s the exact opposite.

Perhaps you’d anger the fairies and they’d rain curses down upon you and yours, or perhaps they’d drag you inside the ring and make you dance with them until you drop dead from exhaustion. Perhaps you might be inveigled into their realm and even if you managed to escape it would be years later with no memory of what happened. All very scary.

The reality is of course less fanciful because these circular growths are actually the fruits of a fungus growing underground spreading its fruit to disperse its spores.

For more on that see Olivia Campbells “How fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitions” in National Geographic May 2024; and for more paintings which include fairy rings see the British Fairies website

So where does that linkage to fairies come from? It’s not actually that obvious. There are just occasional mentions of mushrooms and fairies in 17thc literature. Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream with Oberon, Titania and all their fairies but no references to fungi,. However, in The Tempest he has Prospero allude to a superstition that sheep will not eat the grass that grows in fairy rings.“You demi-puppets that by moonshine do the green-sour ringlets make,

Whereof the ewe not bites, and you whose pastime is to make midnight mushrooms.”

I’ve also found a couple of poetic mentions from the same period. Robert Herrick in Oberon’s Feast talks of ‘a little mushroom table spread” for the fairies to eat from, while in her poem The Pastime of the Queen of Fairies Margaret Cavendish describes how “Queen May and all her Fairy fry,

Dance on a pleasant molehill high”

before “.. to her dinner she goes straight,

Where all her imps in order wait.

Upon a mushroom there is spread

A cover fine of spiders web”

However it’s really only in the later part of the 18thc that this link becomes more obvious and part of more mainstream thinking. A rapid demographic shift was taking place with large-scale rapid migration from the countryside to cities. This was erasing centuries of oral tradition and long-held beliefs about nature and the world and led to a a big revival of interest in folklore across the whole of 18thc Europe

One of those most prominent in Britain for trying to preserve these vanishing beliefs and traditions was the Romantic poet Robert Southey. According to historian Mike Jay, he saw them “as picturesque and semi-sacred, an escape from industrial modernity into an ancient, often pagan land of enchantment”. This all coincided with the growth of nationalism and the desire to create new national histories and cultures. The result can be seen with the “invention” of all the myths about the Druids in Britain; collection and adaptation of of traditional folk stories in Germany by the Brothers Grimm, and even the story of why some Viking went Berserk in Scandinavian histories. Academic explanations of this were not far behind with Thomas Keightly’s The Fairy Mythology published in 18,50 being particularly influential.

Alongside this was a revival in the popularity of Shakespeare’s plays including Midsummer Night’s Dream which was not only staged but became the subject of prints and paintings, especially after the leading print publisher of the late 18thc, and later Lord Mayor of London, John Boydell decided to commissioned work by leading artists including Joshua Reynolds, George Romney and Henry Fuseli for a Shakespeare Gallery.

The interest in Shakespeare continue and with the development of theatrical technology by 1856 the 8 year old Ellen Terry playing Puck, made her entrance on a mechanical mushroom.

However, I think there’s probably yet another side to all this and it’s to do with what might loosely call the magical properties of some fungi. Its summed up in an interesting medical case from October 1799 when a man went collecting mushrooms in Green Park for his family’s breakfast as he often did. [Try doing that now!] This time though something went horribly wrong – his vision became blurred, he saw vivid flashes of colour, lost his balance and found it difficult to walk. His family meanwhile had severe stomach pains, suffered from vertigo and started shivering. He wondered what was happening and stumbled out to get help, but got confused and lost.

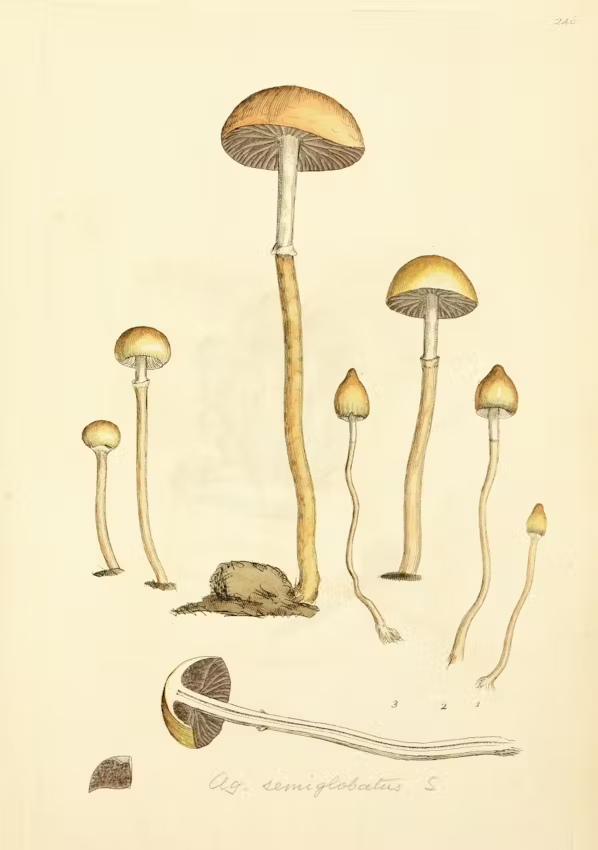

Luckily Dr Everard Brande lived nearby in Arlington Street and was called to assist. He was so intrigued that he wrote up the case in The Medical and Physical Journal. In particular he reported the strange symptoms of 8 year old “Edward S.”,who had “fits of immoderate laughter” , spoke nonsense, and seems to be living in another world. Dr Brande consulted the Professor of Botany at Oxford University who in turn asked James Sowerby who was then working on Coloured Figures of English Fungi or Mushrooms (1803), the first serious study of them in English.

They put the symptoms down to the “deleterious effects of a very common species of agaric [mushroom], not hitherto suspected to be poisonous”. Yet While “Mr. S. has no doubt respecting the species…a variety of the Agaricus,” yet no-one had previously reported any problems from ” its deleterious quality. This may seem singular, as its effects were so strongly marked.”

Sowerby identified the fungus in question and later illustrated it alongside another roughly similar looking species. As you can see there was just a slight difference in the shape of the cap – one was elongated and the other more rounded. Sowerby noted that it was the variety “with the pileus acuminated” ie the more pointy-headed that “nearly proved fatal to a poor family in Piccadilly, London, who were so indiscreet as to stew a quantity” for breakfast.

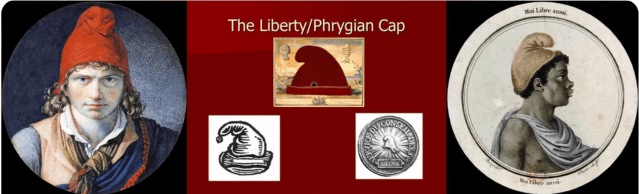

This mushroom was if you hadn’t already guessed Psilocybe semilanceata sometimes known as “the liberty cap” one of the so-called “magic mushrooms” that can be found in many places across the Britain every autumn. Its name comes from its resemblance to the liberty cap adopted by the revolutionaries in both France and America at the end of the 18th century.

Perhaps the strangest part of the story is that the effects of eating this particular mushroom were apparently unknown to the medical profession. That would presumably imply that people were not eating them in Britain at least.

Yet only 30 or so years earlier Carl Linnaeus had published Inebriantia the first-ever list of intoxicating plants from all corners of the world and scientists and medics were becoming more aware of the widespread use of plant and other substances in western and non-western cultures, and many people were using them. Southey for example was a regular user of nitrous oxide or laughing gas.

For more information about Psilocybe semilanceata and indeed the properties of other fungi see Mushroom World

So by the early decades of the 19th century all these associations came together and were almost built in. As Mike Jay points out “The lore of plants and flowers was carefully curated and woven into supernatural tapestries of flower-fairies and enchanted woods, and mushrooms and toadstools popped up everywhere. Fairy rings and toadstool-dwelling elves were recycled through a pictorial culture of motif and decoration until they became emblematic of fairyland itself.”

Heatherley, Fairy Resting on a Mushroom

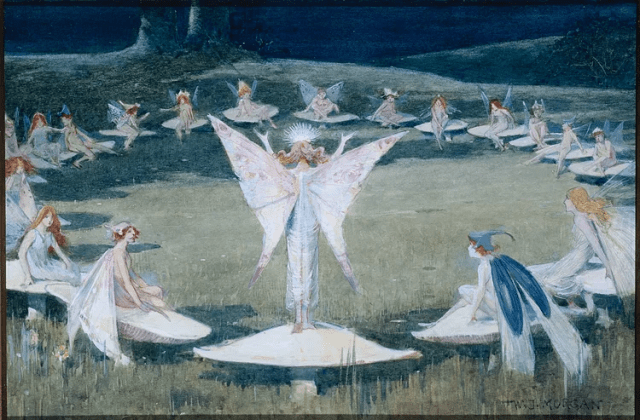

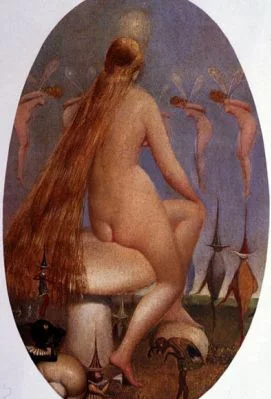

It was to lead to what art historian Jeremy Maas calls the “Golden Age of Fairy Painting” when several painters began to specialise in painting fairies and fairylands. These secret worlds often defied Victorian convention with their inhabitants often scantily clad, cavorting about not just with each other but often with birds, mice, butterflies and other small creatures, and of course often with fungi present. It allowed artists an almost shocking openness about sexuality and physical attraction that would have been scandalous to Victorian society if the characters featured had not been fairies.

Fairies Sitting On Two Flowers Or White Clitocyboid Mushrooms. 1872

Eleanor Vere Boyle

There is a lot of academic art history written about the origins of these paintings which often picks up on the interest in romantiscm and nature, but there’s also a big interest developing in the supernatural and the occult – think for example later of the Cottingley Fairies. At the same time there was a growing exploration of intoxicants and drugs – not just alcohol but laudanum, and almost certainly magic mushrooms as well. I wonder too if it’s significant that two of the leading artists of this kind of painting – Charles Doyle and Richard Dadd -were both mentally ill and in asylums. So while on the surface these paintings are “light” and almost humorous at times they have, in parallel, a more serious, perhaps even sinister side.

Moonlight: fairies, and goblins dancing above a snail and a toadstool

possibly by Thomas Woolner 1870-90

It’s also worth pointing out that fungi don’t just make appearances in paintings, they also play a role in literature. Two examples in particular stand out. One is Jules Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth where the protagonists discover “a high, tufted, dense forest. It was composed of trees of moderate height, formed like umbrellas, with exact geometrical outlines. …I hastened forward. I could not give any name to these singular creations. Were they some of the two hundred thousand species of vegetables known hitherto, …No; when we arrived under their shade my surprise turned into admiration. There stood before me productions of earth, but of gigantic stature, … a forest of mushrooms,”

Even more obvious and famous is the mushroom in Alice in Wonderland, first published in 1865. As I’m sure you’ll remember the blue caterpillar is sitting on a large mushroom smoking a hookah. It tells Alice in a ‘languid, sleepy voice’ that the mushroom is the key to navigating her way because nibbling “one side will make you grow taller, the other side will make you grow shorter”. It takes a while for her to judge the right amount to eat but she continues to partake throughout the rest of the book which helps her through difficult moments such as encountering the Duchess, the March Hare or when entering the secret garden. Additionally there are several other occasions where Alice takes substances during her adventures in Wonderland. For example, she finds a bottle with a little message: Drink Me, and food labelled: Eat Me and soon realises that ”something interesting is sure to happen whenever I eat or drink anything”. All fairly hallucinogenic. It’s no wonder that there has been suspicions that Lewis Carroll had to have had first-hand experience of the mind-bending effects of certain mushrooms and maybe more.

Actually it’s thought unlikely that he personally indulged in magic mushrooms, or indeed any other mind-altering drugs, although he was very interested in such matters from a medical or scientific standpoint. Research by Michael Carmichael showed that he read a copy of The Seven Sisters of Sleep (1860) by Mordecai Cooke in the Bodleian Library. Carmichael suggests that Carroll would have been drawn to it because not only did he have he had seven sisters but he was a lifelong insomniac. [Carmichael’s article “Wonderland Revisited” can be found in Psychedelia Britannica 1997 but is not available on-line]

Cooke’s book looked at seven type of psychoactive substances that were easily available in Victorian Britain: opium, cocaine, cannabis, belladonna, datura, digitalis and Amanita muscaria (the fly agaric mushroom). The Bodleian copy still has most of its pages uncut, with the notable exception of the chapter called ‘The Exile of Siberia’ which is largely about fly agaric and its trance-inducing properties, implying that was the chapter that Carroll read.

These hallucinogenic effects even features as early as 1866 as a element of the plot in Charles Kingsley‘s 1866 novel Hereward the Wake ” : I know where to get scarlet toadstools ; and I put the juice in his men’s ale : they are laughing and roaring now, merrymad every one of them.” That a respected author and Anglican clergyman should know about, and describe such things suggests it was widely

These hallucinogenic effects even features as early as 1866 as a element of the plot in Charles Kingsley‘s 1866 novel Hereward the Wake ” : I know where to get scarlet toadstools ; and I put the juice in his men’s ale : they are laughing and roaring now, merrymad every one of them.” That a respected author and Anglican clergyman should know about, and describe such things suggests it was widely

The reason that is significant is because, whereas most of the early fairy images we have seen the fungi look like field mushrooms or other fairly nondescript species the fly agaric is very distinctive and its not long before it becomes the stock mushroom of fairyland and the realms of the gnome. But can anyone explain why its mainly seen on Christmas ad New Year cards because I have absolutely no idea?

Unfortunately given my word count so far more about that will have to wait for another day…

For more on fly agaric see Soma: Divine Mushroom of Immortality by Gordon Wasson & Wendy Doniger (1968)

For more on fairies in paintings, on the Stage, in writing, book illustrations and music see various essays in the catalogue of the 1997 Royal Academy Exhibition

Fly agaric

You must be logged in to post a comment.