I did a double-take when I saw this relief carving on the house I stayed in at Ubeda in central Spain recently. Heraldry is symbolic but who or what on earth were the two figures supporting the coat of arms of the family who had once lived there? Were they athletic men in fur coats throwing frisbees or…?

Of course, it didn’t take long to realise they were “Wild Men” one of the most delightful and fascinating inventions of the mediaeval imagination, and who persisted in popular culture right through until the late 18thc at least, and are now being used by English Heritage to help visitors understand the landscape and gardens at Belsay Castle in Northumberland.

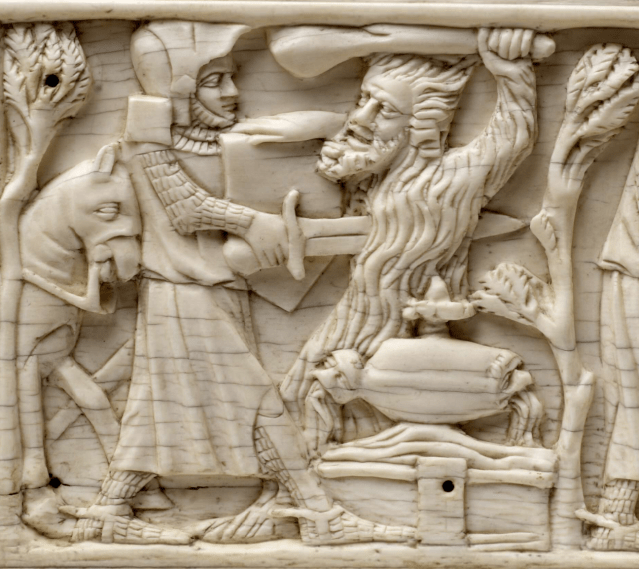

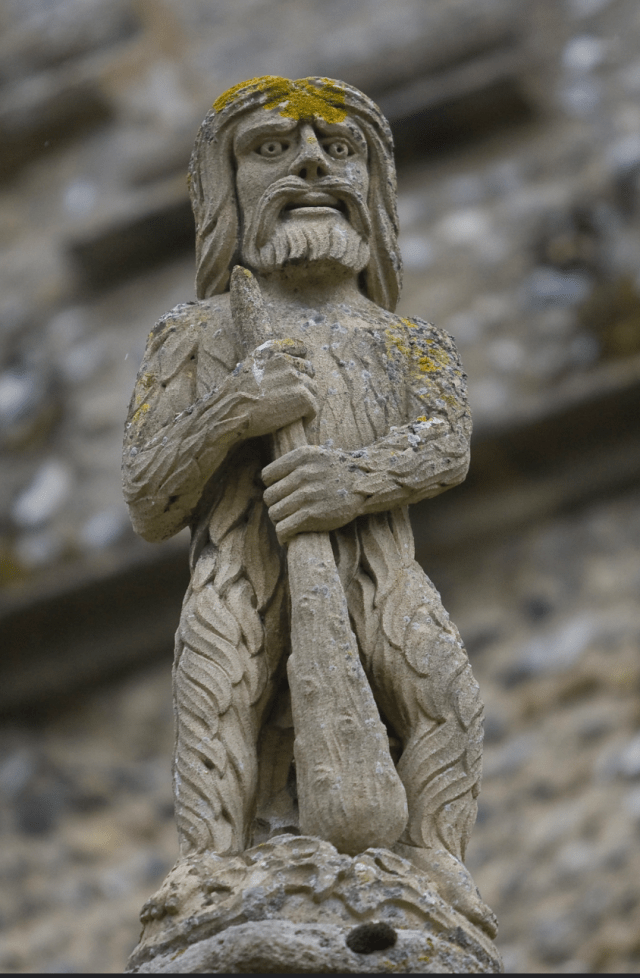

Wild men are big, hairy, primitive, woodland creatures, although they don’t have any animal characteristics, so no hooves, horns or tails. They were usually shown wielding a branch, or even a whole tree, as a club, and sometimes crowned and belted with leaves.

They are part of a long tradition of human-like beings that goes back to Enkidu from the Gilgamesh story, and the satyrs of the Classical world. As a result they are sometimes portrayed as one of the various mythical monstrous people who appear in mediaeval travel accounts and histories. Nevertheless it’s clear that people believed in their existence just as they believed in elves, fairies and hobgoblins. [See for example, Natures embassie: or, The wilde-mans measures by Richard Brathwaite (1621) and for an overview see David Bergeron, English Civic Pageantry.]

Documentary evidence for Wild Men goes back at least to the 11th century in Germany, with the earliest English mention about 1290. They make an appearance in well known stories such as the Arthurian legends with characters like Merlin and Sir Tristram spending time temporarily leading the lives of wild men. According to Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Vita Merlini, [c1150] the magician “ entered the wood… lived on the roots of grasses and on the grass, on the fruit of the trees… He became a silvan man just as though devoted to the woods. For a whole summer after this, hidden like a wild animal, he remained buried in the woods”. A similar transformation happened to Sir Tristram in Thomas Malory’s Morte D ‘Arthur who “was crazed, and ran into the forest and abode there like a wild man many days.”

At the same time, other stories become adapted. For example the Book of Daniel tells how King Nebuchadnezzar goes mad, but while some images have him crawling round naked, he is also often portrayed as a wild man.

Christian imagery then takes this one stage further with religious hermits and anchorites, like St John Chrysostom or St Onuphrious also morphing into wild men.

Saint Onuphrius, c. 1480-1500,

The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

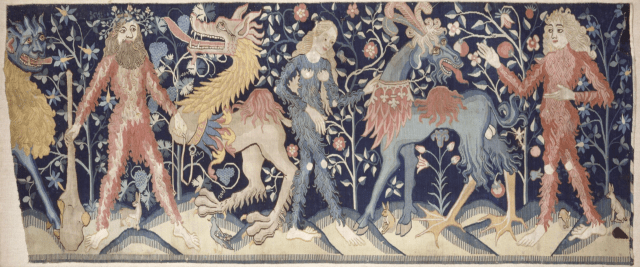

The idea takes hold especially in the German speaking world where Wild Men and other fabulous beasts become significant themes in art, poetry and pageants. By the 15th century there are a series of tapestries produced mainly in the Rhineland, Alsace and Switzerland devoted to Wild Men.

They appear too in the jokey borders of illuminated manuscripts, carved on misericords in churches, forged in metalwork.and even as a suit in a pack of playing cards.

The obvious question is why and the obvious answer is that this is the age of courtly love and chivalry told in stories like Roman de la Rose .

The Wild Man serves as the opposite to the ideal figure of the knight. Whereas the knight is brave but gentle in conduct, and represents order, civilisation and stability, the Wild Man is primitive, savage, sometimes even cannibalistic. He lives away from human society and civilisation in the forest or wilderness [which was always seen as a place of disorder and fear]. The two were often in conflict.

For example, in 1515 at a Twelfth Night entertainment for Henry VIII at Greenwich Palace Hall’s Chronicle tell us that “sodainly came oute of a place lyke a wood viii. wyldemen, all apparayled in grene mosse, made with slyued sylke, with Uggly weapons and terrible visages, and there foughte with the knyghtes viii to viii. & after long fighting, the armed knightes drave the wylde men out of their places.”

Later in 1590, Edmund Spencer’s epic poem Faerie Queene has “a Wilde and salvage man, yet was no man, but only like in shape.”, and “all overgrowne with hair”. He had “huge teeth like to a tusked bore with eares more great than the eares of Elephants”, and was of course naked apart from a wreath of green yew around his waist. He was “fed by the milk of wolves and tygers… and liv’d all on rauin and on rape… and fed on fleshly gore.”

However, as so often is the case, the obvious answer is not quite as simple as it might seem. While that general picture of the world of the Wild Man and the forest being dangerous and foreboding holds true for the medieval period, by the 16th century another view of the the natural world was emerging. This was of a peaceful Arcadia, even an enclosed garden where lions and lambs sat at the feet of the Virgin and Child. Now Wild Men were thought to have a natural innocence which could be tamed and turned to good. Although they still lived in the forest they could become more domesticated, have wives and children and be less violent. This association of forests with family life and love is paralleled in later courtly romantic comedies such as Midsummer Night’s Dream or Shakespeare’s Forest of Arden. This softer version of the Wild Man was to lead gradually to the idea of the Noble Savage. By the later Elizabethan period this second, more sympathetic way of seeing the wild man – and indeed wild woman – become more prevalent. While Spencer’s Faerie Queene had the “Wilde and salvage man” who serves as a suitable villain later in the poem he has another Wild Man who acts as a loyal protector to one of the heroines. Despite his “ruder hart”, and the fact he has never experienced ‘pittie’ or ‘gentlesse’ before,”the Salvage Man” rescues two women from a tormenter because he begins to ‘feele compassion’ for them. Having led them ‘Farre in the forrest… that wyld man did apply / His best endevour, and his daily paine, / In seeking all the woods both farre and nye / For herbs to dress their wounds’.

Le Bal des Sauvages from a 15th-century miniature from Froissart’s Chronicles. British Library Harley 4380

Wild Men can be also seen in court masques where they served as a stock character allowing courtiers to dress up and play the fool. An early example of this is Le Bal des Sauvages [The Dance of the Wild Men] a royal entertainment in Paris in 1393. Six young men, including the king Charles VI, dressed as Wild Men Their costumes and masks were made out of linen soaked with resin to which flax was attached “so that they appeared shaggy and hairy from head to foot”. Unfortunately a naked flame from a torch set light to one of the costumes and four of the courtiers were burned to death with many others injured trying to save them. The tragedy is now better known as Le Bal des Ardents [The dance of the Burning Men] For more on the story follow this link.

The new more sympathetic version of the Wild Man appears in some of the lavish entertainments laid on for Queen Elizabeth I by her couriers during her progresses around the country. There is a lengthy eye-witness account of what Robert Dudley organised in the grand new gardens at Kenilworth in 1575.

“About nine o’clock, at the hither part of the chase, where torch light attended, out of the woods, in her majesty’s return, there came roughly forth Hombre Salvagio [ie. a Savage Man] with an oaken plant plucked up by the roots in his hand, himself foregrown all in moss and ivy; who, for personage, gesture, and utterance beside, countenanced the matter to very good liking; and had speech to this effect:—That continuing so long in these wild wastes wherein oft had he fared both far and near, yet happed he never to see so glorious an assembly before” …and eventually after much flattery “he reported the incredible joy that all estates in the land have always of her highness wheresoever she came ”

For more the Kenilworth entertainment see the English Heritage website, especially the pages on the Elizabethan garden.

Viscount Montague laid on another extravaganza for her in 1591 at Cowdray. “After dinner she came to view my lord’s Walks, where she was met by a Pilgrim,…” who led her “to an Oak not far off, whereon her Majesty’s Arms, and all the Arms of the noblemen and gentlemen of that Shire, were hanged in escutcheons most beautiful. And a Wild Man clad in ivy, at the sight of her Highness spoke…the Wild Man’s Speech at the Tree’ etc etc.

For more on Cowdray entertainment see An Audience with the Queen by Birgit Oehle, 1999

Not to be outdone Lord Burghley entertained the queen at Theobalds, his Hertfordshire estate. Baron Waldstein, a Moravian nobleman, on his travels to England put a very brief note in his diary that the play included a “a man and a woman dressed, like wild men of the woods, and the number of animals creeping through the bushes.”

Wild Men have a place in architecture too. John Thorpe the architect of several great Elizabethan mansions even used the tiny figure of one to give scale to his drawing of “how to Foreshorten”.

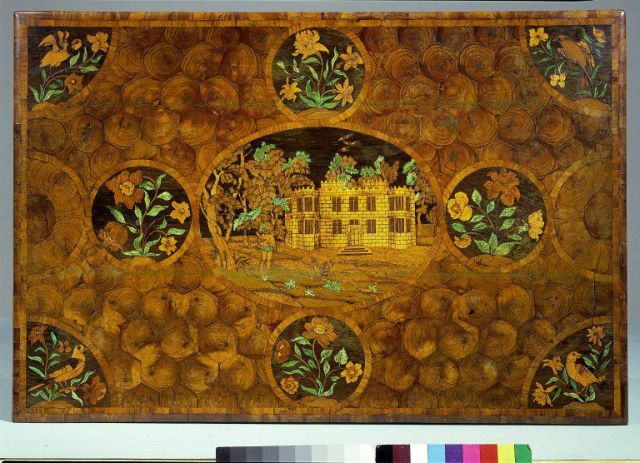

They also appear as architectural features on chimney pieces, fountains, furniture, door portals, even including on churches, with a group in Suffolk being particularly evident. There are also several inns named The Wild Man, again particularly in East Anglia, with examples near Bury, at Sproughton nr Ipswich,Norwich and Wicklewood in Norfolk.

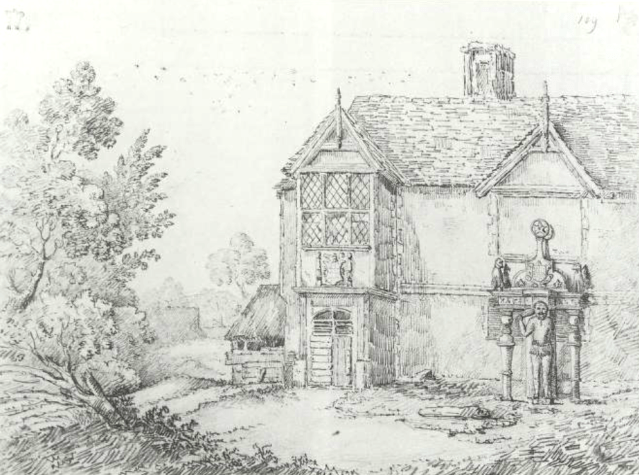

This may explain the best surviving example of a Wild Man figure in a garden which is also in Suffolk, and which is discussed briefly by Paula Henderson in Tudor Houses and Gardens.

It was a huge figure- 8 feet [2.44 m] tall. It formed the central feature of a fountain erected at the front of Hawstead Place in Suffolk for a visit by Queen Elizabeth in 1578. She planted three oriental plane trees in the parkland which still survive and are now the largest in the country.

There is also a drawing of it in the British Museum, although it’s not in the on-line collection, as well as a lengthy commentary about it written before the house was demolished around 1820. “Immediately upon your peeping through the wicket, the first object that unavoidably struck you, was a stone figure of Hercules*[this was footnoted with the next paragraph], as it was called, holding in one hand a club across his shoulders, the other resting on one hip, discharging a perennial stream of water, by the urinary passage, into a carved stone basin. On the pedestal of the statue is preserved the date, 1578, which was the year the queen graced this house with her presence; so that doubtless this was one of the embellishments bestowed upon the place against a royal visit. Modern times would scarcely devise such a piece of sculpture as an amusing spectacle for a virgin princess. A fountain was generally (yet surely injudiciously in this climate) esteemed a proper ornament for the inner court of a great house. This, which still continues to flow, was supplied with water by wooden pipes, at no small expense, from a pond near half a mile off.The footnote read: “Perhaps he might be designed to represent a wild man, or savage, having no attribute of Hercules but his club, and all his limbs being covered with thick hair, and his loins surrounded with a girdle of foliage. He resembles much the supporters of the arms of the late lord Berkley of Stratton, and of the present Sir John Wodehouse. Hombre Salvagio, just come out of the woods, with an oaken plant in his hand, and forgrown with moss and ivy, was one of the personages that addressed queen Elizabeth at her famous entertainment at Kenelworth Castle.”

[I can’t add a link direct to the description but google Hawstead Book by Cullum Part 3 2016.pdf. Adobe Acrobat document [942.3 KB]. and you can reda/download it]

The statue surprisingly wasn’t demolished along with everything else but still stands in the grounds of the surviving medieval barn which is now a wedding venue in the parkland of the former house.

So Wild Men seem very much at home in Elizabethan England but these progresses with their accompanying entertainments begin to fade away under James I largely one suspects because of the huge costs involved [See David Bergeron’s comments if you want to know more] so the “public” appearances of wild men does tend to fade.

However one place that Wild Men remain prominent is in heraldry where they are used, usually in pairs, as supporters for coats of arms, a good example being those of Anne of Denmark. although in her case that’s not surprising as they are also the supporters of arms of the Danish crown.

As a quick guide wikipedia has 127 examples mainly from Germany, Scandinavia and central Europe, but they also appear on the arms of several cities including Antwerp and those of quite a few English aristocratic families. That has given them a new lease of life recently because one of the families whose arms included Wild Men are the Middletons of Belsay Hall and Castle in Northumberland where one features as the crest.

English Heritage who now manage the estate commissioned Rebecca Mileham to find new ways of introducing the estate to visitors, and between them they came up with the idea of using the Middleton’s Wild Man. You can see a short video clip about it by following this link

Good to see the Wild Man still has a part to play in our imagination!

You must be logged in to post a comment.