I wonder if you’ve heard of Philip Miller. If you’re not a garden historian then probably not, but he was probably the most influential British horticulturist and garden writer of the eighteenth century, amongst other things writing the first dictionary of gardening. A member of the Royal Society, his reputation stretched not just across Britain, but its colonies and most of Europe.

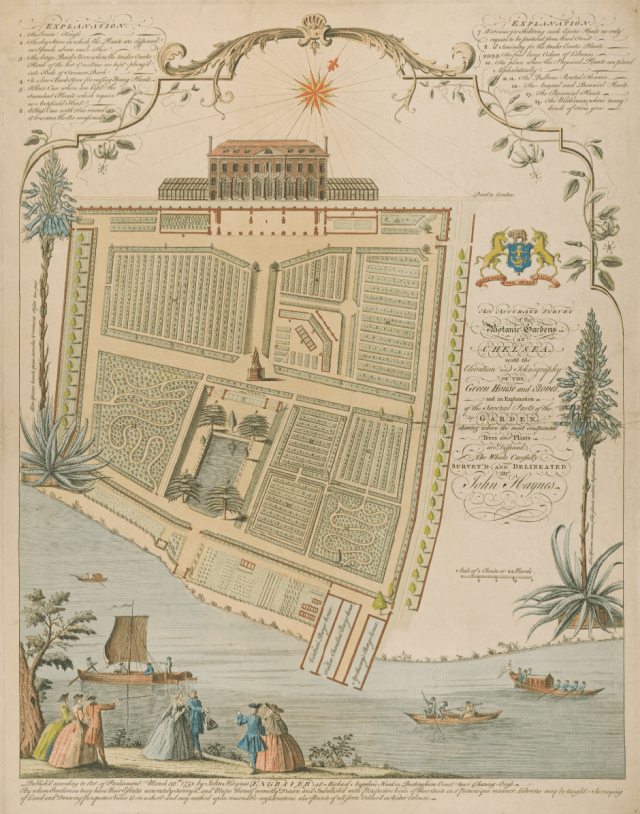

Miller was also in charge of Chelsea Physic Garden for nearly 50 years, turning it into the leading botanic garden and hub of horticultural knowledge of the day. As a result he knew everyone of any importance connected with horticulture: aristocratic landowners, medics, scientists, plant collectors, and nurserymen, both at home and abroad.

Like so many other prominent gardeners of the time Miller had Scottish origins but his father had come south to work, first as gardener on an estate at Bromley in Kent, but then as a market gardener at Deptford. Philip was born in 1691 and trained with his father but, according to an early biographer who interviewed people who knew Miller, he was “extremely fond of flowers and plants, and anxious to devote himself more particularly to the cultivation of his favourite pursuit, he very early commenced business as a florist and grower of ornamental shrubs, on a piece of ground in part of St. George’s Fields.” He also travelled extensively round Britain, and then Flanders and Holland looking at both kitchen and ornamental gardens. On his return he became “much employed in planting and laying out gardens round the metropolis” and offering advice to other gardeners including “Ellis who was then the foreman of the Chelsea garden.”

The “Chelsea garden” belonged to the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries who had initially established a physic garden in the grounds of Danvers House in 1673 [for more on the original garden there see this earlier post] but financial difficulties dogged them there and the garden did not flourish. Luckily a benefactor was at hand. In 1713 Sir Hans Sloane, whose statue now stands in the garden, purchased the manor of Chelsea which included the garden site and in 1722 leased the site to them for £5 a year in perpetuity, with the proviso that it was to remain a garden. In addition to the rent Sloane also added the requirement that they deliver 50 herbarium specimens from plants grown in the garden to the Royal Society every year.

Now the garden’s future was assured it needed someone to take charge. Patrick Blair, a Scottish doctor and author of Botanik Essays (1720), wrote to Sloane, recommending Miller who he said had “an easy and familiar way of expressing his thoughts, such a delight for improvement and so much exactness and dilligence in the making of observations that I look upon him to go onward with a curiosity and genious superior to most of his occupation”, and in due course he was appointed.

Over the next few years there were considerable improvements to the gardens, notably in 1727, the construction of a large greenhouse/orangery. Upstairs, which was 180 ft long, contained the library, meeting room and accommodation for the gardener. At some point soon after this Miller married and during 1730s had 3 children, Mary, Philip, and Charles. Perhaps the living space became a little cramped and by 1734 the family had moved to a house in Swan Walk, next door to the garden.

Miller showed his gratitude to Sloane by dedicating his first book the two volume The Gardeners and Florists Dictionary to him in 1724. It was a mammoth task stretching to about 1000 pages, largely drawn from the work of others including Stephen Switzer, John Laurence, Thomas Fairchild, Richard Bradley and Louis Liger. The book was, recommended “as highly useful and necessary for all lovers of gardening” by ten of the leading nurserymen around London. It was particularly useful for Robert Furber, because at the end Miller included a lengthy catalogue of plants that were obtainable from his nursery in Kensington, perhaps because Miller had taken on Furber’s son William as an apprentice.

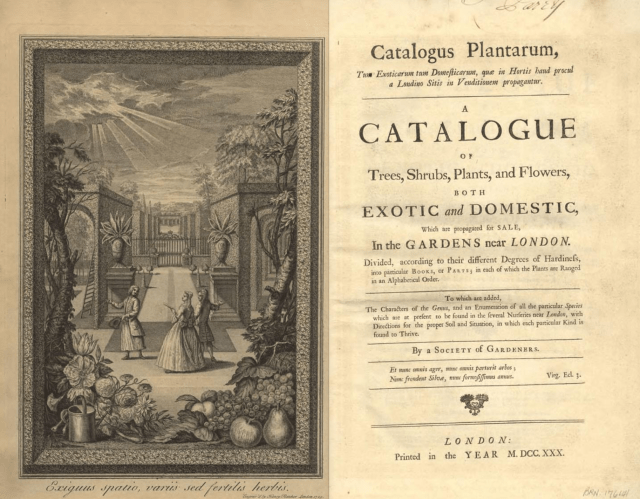

This group of nurserymen, later grew to about twenty in number, and were “united in a Society for the improvement of gardening” and who were to set up the Society of Gardeners with Miller acting as its secretary. In 1730 the Society published the Catalogue Plantarum, which was a co-operative effort listing of all the plants that were available from these nurseries around London. In the end only the first part, covering trees and shrubs, actually appeared.

Many of the plants listed were imports from Britain’s North American colonies and probably available by Thomas Fairchild of Hoxton and Christopher Gray of Fulham. They had both received plants from Mark Catesby, the naturalist who had first travelled to North America in 1712 but then was commissioned by members of the Royal Society to undertake a plant-collecting expedition in 1722

The Catalogus was not just a boring list of plants but was the first nursery list to include illustrations. Not only was there a frontispiece of a formal garden with a gardener talking to clients or perhaps employer, but there were a further 21 plates, some of which were intended for a second part which was never produced. They were drawn by Jacob van Heysum, a Dutch flower painter and botanical artist who had moved to London and already produced the images for John Martyn’s Historia plantarum rariorum which featured newly imported plants growing at Chelsea Physic Garden and the gardens at Cambridge University.

The Catalogus stressed that “In all we promise the publick to be as careful as possible not to lead them into mistakes, nor will we mention any particular tree, plant, flower or fruit which is not in our own garden … we do not propose to mention many different species of trees and plants that are either in the Public Botanick Garden, nor that may be in the possession of some curious gentlemen, but only such as are actually in the nurseries of persons belonging to this Society and from where any Gentleman may be furnished with any of the particulars here treated of by directing their letters for the Society of Gardeners at Newhall’s Coffee House in Chelsea, Nr. London, at the easiest rates.”

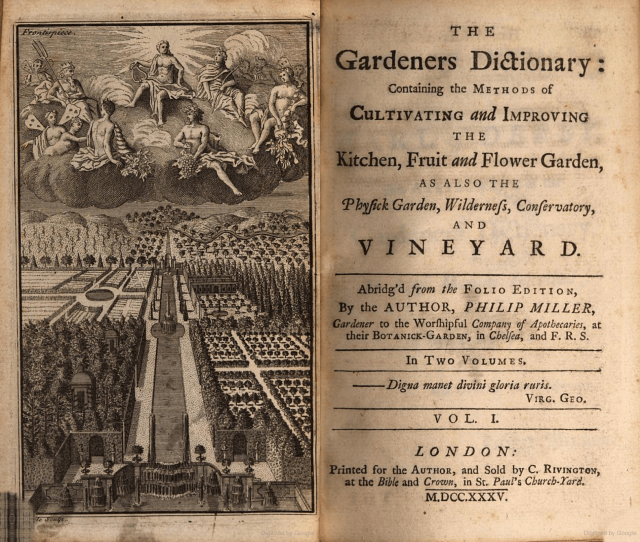

The follow year Miller published “from papers entrusted to his care” the first edition of The Gardeners Dictionary which was issued by subscription in two formats, a quarto version for £1.10s and a larger one for £2. It was dedicated to Sloane and the Royal Society who RS returned “their unanimous thanks for that excellent useful work” when they received their presentation copy.

There were about 400 subscribers to the dictionary across the whole range of both society and the profession – several aristocrats even bought a second copy for their gardener. It was bought for the King of Prussia and the Governor of South Carolina as well as by several leading nurserymen and was available from 16 booksellers spread right across the country. It was a great success from the very first and was to go through a further seven editions during Miller’s lifetime. Unfortunately not all of these editions are available on-line, or even in the British Library.

Besides horticulture, Miller included coverage of agriculture, arboriculture, and even wine making.

It was not long before the dictionary was translated and published in France, Holland and Germany, and by the third edition he was complaining that his work was being pirated.

The Dictionary also contributed a great deal to early taxonomy, with the 1752 edition particularly significant in taxonomy because it has been designated “the official starting point for the nomenclature of cultivars of cultivated plants” and is regarded as second in importance only to Linnaeus’s Species plantarum which was published the following year 1753.

Miller didn’t initially approve of Linnaeus’ binomial system so right up the 7th edition used the classification devised by Joseph Pitton de Tournefort in 1700. He insisted he was “unwilling to introduce any new Names, where the old established names were suitable, lest, by this, he should rather puzzle, than interest, the Lovers of Gardens”.

However he eventually adopted the new system in 1768 for the 8th and final edition published in his lifetime. It was monumental – running to well over 1300 pages and weighing about 8kg. In it he also gave names of his own to species not recorded by Linnaeus and noted that the “number of plants now cultivated in England is more than double those which were here when the first edition of this book was published.” The several hundred new botanical names published there by Miller led botanical historian William Stearn to argue the book had lasting botanical importance.

The 3 images below are from the 8th edition 1768.

Miller’s dictionary is actually encyclopaedic. Throughout he conscientiously sought advice and information from other experts from home and abroad, acknowledging their contributions in the text. In the preface to the 7th edition Miller is clear that he was not taking his information second hand but direct “from Nature” with “the far greater number from growing plants which the author has under his care and the others are from dried samples, which are well preserved : of which he has, perhaps,as large a collection as can be found in the possession of any private person.”

Miller’s dictionary is actually encyclopaedic. Throughout he conscientiously sought advice and information from other experts from home and abroad, acknowledging their contributions in the text. In the preface to the 7th edition Miller is clear that he was not taking his information second hand but direct “from Nature” with “the far greater number from growing plants which the author has under his care and the others are from dried samples, which are well preserved : of which he has, perhaps,as large a collection as can be found in the possession of any private person.”

Between the preface and the text proper of the Dictionary is an explanation of botanical terminology, with three pages of illustration showing the different parts of plants, various fruits and the structure of flowers. A fourth plate illustrates the system of Linnaeus.

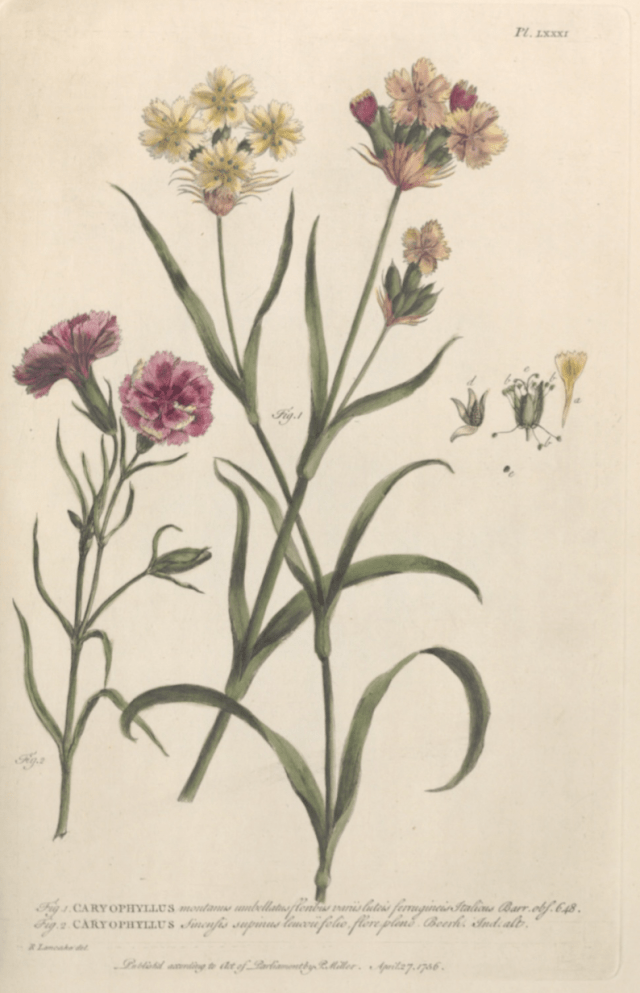

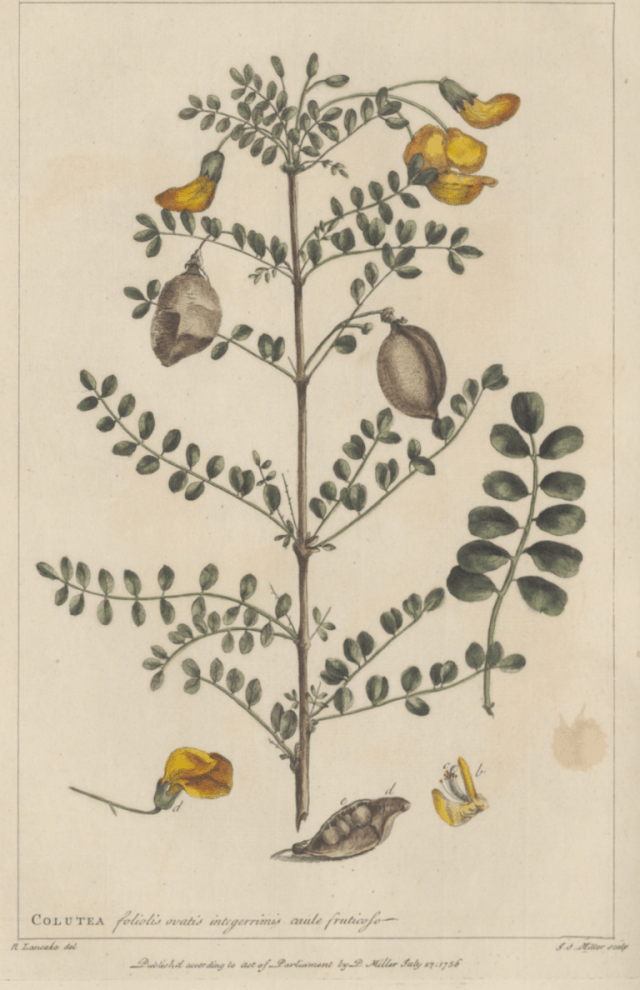

The colour plates below all come from The figures of plants, being the most beautiful, useful and uncommon plants described in The gardeners dictionary on 300 copper plates. published 1755-60

The thousands of entries cover plants from Abies alba to Zygophyllum fuluum and included some from every corner of the then known world including Japan and China. Most have practical advice on cultivation even of exotics such as melons, citrus, and pineapples drawn from his own experience or that of other respected horticulturists.

There are entries dealing with techniques ranging from inarching to pruning, and forcing to growing wall fruit. Problems such a blights, caterpillars and earwigs are covered as are design features such as avenues, borders, edges, groves, and hedges, and there is even statistical information about rainfall.

Even the bibliography is comprehensive and includes no less than 120 works the earliest dating back to 1558.

Unfortunately there were few illustrations but between 1755 and 1760 he oversaw an additional publication which overcame that problem. The figures of plants, being the most beautiful, useful and uncommon plants described in The gardeners dictionary on 300 copper plates. This came in two handsome folio volumes, and was commended at the time for being drawn from nature in the best state of flowering, and for including illustrations of fruit and seed as they ripened.

Most of the images are by Georg Dionysus Ehret, the great German botanical artist who married Miller’s sister-in- law, while others are by other German artist Johann Mueller, usually known in Britain as John Miller.

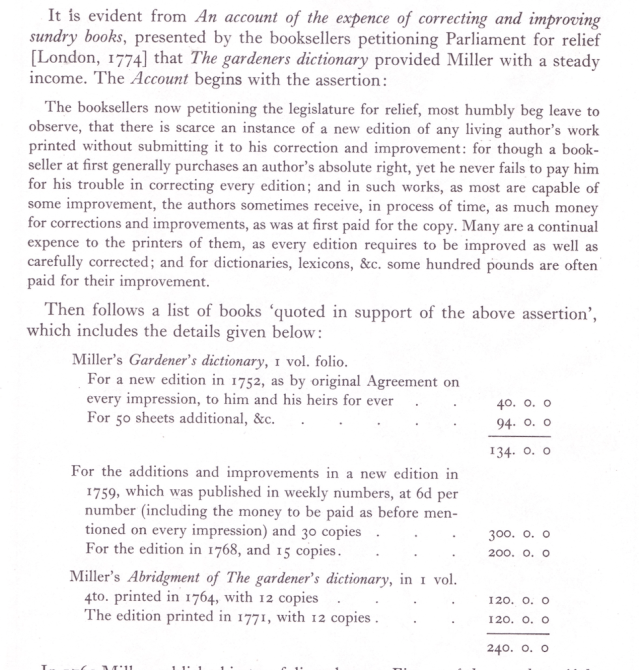

Miller must have been conscious that the dictionary was expensive so he also produced an Abridgement in eight editions (1735–71) and a practical, even cheaper, Gardeners Kalendar in fifteen editions (1731–69). These various publications provided him with a sizeable regular income – which can be deduced from evidence presented in a petition to Parliament about copyright in 1774.

[Unfortunately this is not available on-line and it’s too complex to cite the figures in a meaningful way, but I’ve scanned a couple of extracts from Blanche Henrey’s “British Botanical and Horticultural Literature” and added them right at the end of this post which show he was able to sell shares of the royalties in advance for quite substantial sums].

Alongside his writing Miller also had a garden to supervise, and correspondence to keep up with an almost global network of botanists, collectors and nurserymen. Notable amongst them was his long-distance friendship with John Bartram of Philadelphia.

Miller was also a regular advisor to Lord Petre first at Ingatestone and then Thorndon, and to the Duke of Bedford at Woburn who paid him £20pa from 1740 to 1753 “for inspecting my Gardens hot houses, pruning the trees, etc. and to come to Woburn at least twice a year and oftner if wanted.” After Petre died his plant collection at Thorndon was up for sale Miller acted for the Duke to purchase anything he thought suitable for Woburn. He was also on good terms with the Dukes of Richmond – with whom he sponsored Bartram’s collecting expeditions -and Northumberland to whom he dedicated the last 3 editions of the Dictionary and must also have known many other aristocrats and their gardeners because specific plants from their collections are mentioned in the dictionary.

Visitors to Chelsea could usually expect a warm welcome, and it was clearly possible to get seeds or plants from him too. For example Horace Walpole sent his brother, Ned, to collect tea seed, while Charles Hatton, who developed the gardens at Kirby with his brother Viscount Hatton [see earlier post] selected two pots of passion flower, ‘lusty and strong’. So it’s no wonder that a Swedish visitor Pehr Kalm observed that “the principal people in the land set a particular value on this man.”

Much of this was recorded in his diary [sadly no longer extant] or the notes of those who encountered him and shows that his skill at writing was matched by his expertise in both theoretical and practical horticulture. Early in his career he wrote papers for the Royal Society. including one in 1728 on the cultivation of the coconut (see p. 39) and other hard-shelled seeds previously considered impossible to grow in this country. This recounts his experiments over a three year period with batches of fresh coconuts sent over from Barbados, and when he was finally successful how it was verified by other gardeners repeating bis success. Another in 1733 on how bulbs such as tulips, narcissi and hyacinths could be grown in vases filled with water, and again with an account of his methods.

Towards the end of his life Miller left Swan Walk and returned to the accommodation over the greenhouse but sadly although generally the committee of the Apothecaries which oversaw the garden had left him to his own devices there was obviously a clash of personalities and styles. In November 1770 Miller agreed to resign in return for a pension of £60 and alternative accommodation in Chelsea. He died the following year on 18 December 1771 and was buried in the churchyard of Chelsea Old Church where an obelisk was eventually erected by fellows of the Linnaean and Horticultural Societies in 1810.

After his death his herbarium which consisted largely of plants grown at Chelsea was bought by Joseph Banks in 1774 and is now included in the Natural History herbarium.

But the dictionary lived on after him. In 1794, three years after Miller’s death Thomas Martyn published a Companion to it and followed it up with a re-issue of the Dictionary itself in parts; then a 9th edition in 1807. Another edition this time edited by George Don appeared in parts between 1832 and 1838.

As John Rogers his first biographer said: “Medicine, botany, agriculture and manufactures are all indebted to him” and he rated the Dictionary “as the first bright beam of gardening issuing from the dark cloud of ignorance in which it had previously been enveloped; but having once broken through, it had continued to shine with increasing splendour for the last century. It may be almost said to have laid the foundation of the horticultural taste and knowledge in Europe.”

For more information the best place to start is Hazel Le Rougetel, The Chelsea gardener, Philip Miller, 1691–1771 (1990) which is available free on-line. There is also William Stearn’s article ‘Miller’s “Gardeners’ dictionary”’, Journal of the Society of the Bibliography of Natural History, 7 (1974–6) but it’s not available for free on-line.

For more information the best place to start is Hazel Le Rougetel, The Chelsea gardener, Philip Miller, 1691–1771 (1990) which is available free on-line. There is also William Stearn’s article ‘Miller’s “Gardeners’ dictionary”’, Journal of the Society of the Bibliography of Natural History, 7 (1974–6) but it’s not available for free on-line.

His first biographer was John Rogers in The vegetable cultivator (1839).who talked to people who remembered Miller in old age. The other first hand account is by Per Kalm, Kalm’s account of his visit to England on his way to America in 1748, trans. J. Lucas (1892)

Scans of Miller’s financial dealings over the Dictionary are below.

from p.219

You must be logged in to post a comment.