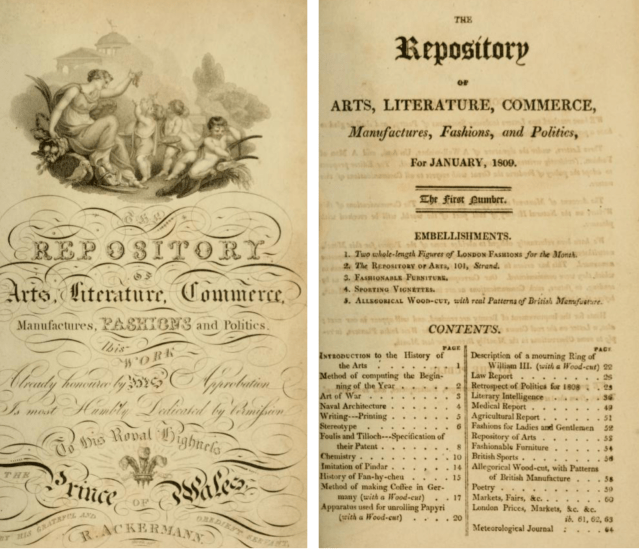

Ever since I’ve been researching garden history, one of my regular sources for information about gardens in the Regency period has been Ackermann’s Repository of arts an illustrated monthly British periodical that was published between 1809 and 1828.

I was searching through a copy the other day looking for an image for a lecture and suddenly realised that not only didn’t I know much about the magazine and its garden-related articles and pictures, but I actually knew nothing about Ackermann himself.

So off down another research rabbit hole….

Rudolph Ackermann, attrib.to François Nicholas Mouchet, 1810–14

© National Portrait Gallery

Rudolph Ackermann was born near Leipzig in Saxony in 1764. As a child he had no real connection with the arts at all, yet by the end of his life not only had he built two successful business careers in London – one in a practical trade, and another as a pioneer publisher of high quality illustrated books. but in doing so he had became one of the arbiters of taste in Regency Britain…and that included houses and gardens

His father was a saddler and aged 15 Rudolph followed in his footsteps, before changing his mind and not only learned to draw and engrave, but trained to work as a carriage designer. He was so successful that in 1787, aged only twenty-three, he moved to London soon landing a commission to design a state coach for the lord lieutenant of Ireland, and another for George Washington.

He went on to publish 13 books of carriage designs between 1791 and 1820. One of these at least employed the flap technique devised by Humphry Repton for his Red Books, to show variations and possibilities in design.

At the same time he mixed with others from the German community in London. This included several who worked as engravers for the leading print publisher John Boydell. They must have had a great influence on him because he branched out from carriages and opened a drawing school.

Ackermann was nothing if not ambitious. That led to him publishing drawing books and decorative hand-coloured prints, including over 100 by Rowlandson. Next he went into the art market selling old master paintings, as well as artists’ materials and taking out a patent for waterproofing of paper and cloth. And just to prove there was almost no end to his talent he was also a pioneer in the use of gas for lighting.

As the Spanish empire in South America was breaking up he sent his son George out to Mexico to open a shop and publishing business to cash in on the newly independent states that were emerging. George became interested in plants and on his return brought with him an important collection of plants which he presented to the botanic garden in Sloane Street, Chelsea, with Kew naming one new specimen Cereus Ackermanii. In addition to all this Rudolph was still designing carriages including one for the pope in 1804 and the one that carried Lord Nelson’s coffin.

More importantly Ackermann was naturalised as a British citizen in 1807 and became a pioneer printer. He set up the first significant lithographic press in England, specialising in publishing high quality colour plate books.

He started with several topographical subjects, all with aquatint plates and all of which were originally issued in parts. First was The Microcosm of London, between 1808 and 1810, followed by Westminster Abbey (1811–12), Oxford (1813–14), Cambridge (1814–15), and The Public Schools (1816) ad the most lavish of all, John Nash’s Royal Pavilion, in 1826, He also published the three Tours of Dr Syntax (1812, 1820, and 1821), featuring the amusing adventures of a naïve rake-thin clergyman, which became runaway best-sellers. [For more on Syntax see this earlier post]. In 1822 he also introduced the earliest British-published literary annual, Forget Me Not which proved an unprecedented commercial success, selling 20,000 copies a year.

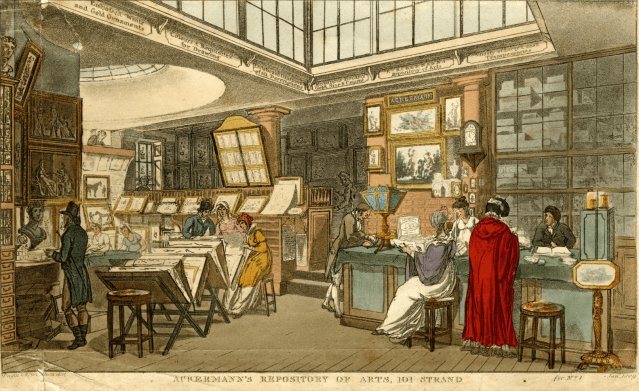

All these businesses were run from his shop on the Strand which was called The Repository of Arts.

So it’s not surprising that also became the name he gave to his monthly journal which featuring fashion and social and literary news, which is what he’s probably best remembered today. The Repository of arts, literature, commerce, manufactures, fashions, and politics, which for obvious reasons is usually shorted to The Repository of arts or sometimes Ackermann’s Repository which ran between 1809 and 1828. It was then, and remains still, an important sourcebook for Regency style, carrying several regular features in every issues about subjects such as fashion and furniture. There were also a wide variety of other shorter series such as one on popular London streets and one called “Hints on Ornamental Gardening”.

Although “Hints” has similarities to much of Humphry Repton’s work, the text is nowhere near as sophisticated – and in any case Repton had died in 1818 two years before the series started. No author was named for these gardening articles, nor was there a named artist for the accompanying plates. However, a selection of the original 34 articles was later republished under. the same title by architect John Buonarotti Papworth who I’ve written about in an earlier post. I’m sure that Papworth had aspirations to be Repton’s successor – he was certainly as much of a social snob – although he didn’t have quite as much talent [no doubt `I’ll now be sued for defamation by Papworth fans]

Earlier in 1816 and 1817 there had been a similar series called “Architectural Hints” also probably by Papworth.

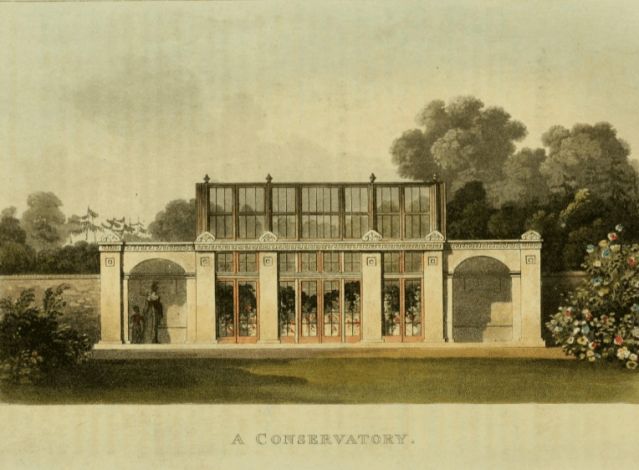

That series included a design for a conservatory, and the accompanying commentary show how such buildings were now almost de rigeur in elite properties. Apart from “the embellishment they afford to garden scenery”, this was partly because “the study of botany has long been added to the catalogue of rural amusements” and partly because it “gives an apartment highly valuable from its beauty and cheerfulness” where plants “are arranged for display, merely allowing space for walks or a promenade, and is frequently used as a breakfast or morning room.”

A second conservatory appeared later in the gardening series. Apart from the buildings themselves what’s interesting is what they reveal about other aspects of the fashionable garden of the day both on style and planting.

The Architectural Hints series also has comments about garden,, although, as with the Cottage Ornee (above )it was generally showing how they complemented the buildings. For example the roof of the verandah was “supported by the stems of small trees, and an occasional trellis-work introduced for the purpose of receiving ornamental foliage, which may be entwined about it: indeed, the construction of’ this cottage would allow so extensive an application of plants that the lower apartments might be completely embowered.”

After discussing the design at length the author then moves on to discuss the cottage of the husbandman “where the style cannot be too simple…the symbols of luxury and ease are incongruous with his laborious life…and ought therefore to be be omitted” .

There is no image of a husbandman’s cottage but the description gave Papworth an opportunity to reinforce the moral message that for the labouring class gardening is better than the alehouse and should therefore be encouraged by the provision of a small plot with each cottage. “There is no important work so cheaply effected, perhaps, as thus amending the condition of the poor, in thus allowing them the exercise of so much of the natural pride of the human heart as may be innocently effective of the works of pride; and happy indeed is he who feels its influence, and evinces it only by the neatness of his habitation, and by the quantity or quality of the vegetable which, by his care and industry, his little garden produces.”

“Hints on Ornamental Gardening” began in January 1819. The articles, like those for Architectural hints, were generally showcased as the first piece in each issue but they were short, usually less than one page of text with an accompanying print making a double page opening spread. The opening paragraph explained that “rural embellishment has become so general a pursuit, and so few works have been written on the subject, except of a voluminous nature… that we trust our readers will approve the introduction of ‘Hints on ornamental Gardening’ in the pages of the Repository ; particularly as they will be accompanied by designs for such decorative buildings as are practicable, useful, and convenient.”

In the two series there were several designs of garden buildings for estate staff. The gamekeeper and the gardener both deserved something better than the labourers cottage. Apart from the kitchen and living room the gardeners cottage also had “a seed closet” and “an implement closet” on the ground floor, while “the overhanging roof and spacious porch give ample room for drying of herbs”. But as was the case with Loudon’s cottages both were as much for the onlooker as the occupant, and here the gardener’s porch, “embowered in clematis, jessamine, and the woodbines, must be picturesque” while the surface beneath the eaves of the building, when decorated with roses and other appropriate flowers, would add to its rural interest.”

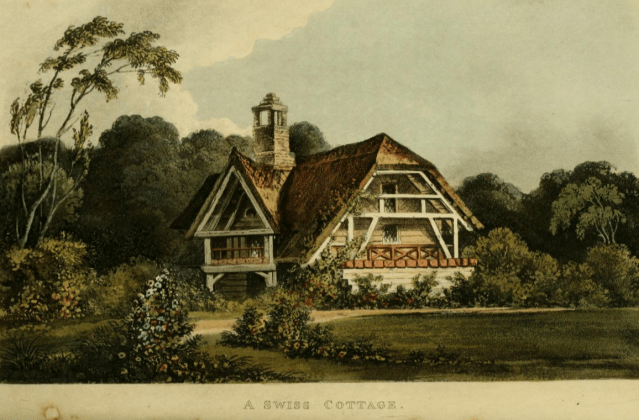

Also designed for a gardener was this Swiss Cottage, which, in addition to the same facilities for drying herbs etc, will “either be beautifully in unison with the most decorated part of the garden, as it is fully ornamented by its inhabitant; or will accord with a more romantic character of the scene if these embellishments are not supplied.” It was of course to be done on the cheap and “may be executed by any ingenious carpenter, and if in the neighbourhood of a cheap supply of timber, …at a small expense, as its construction is entirely of wood, the chimney excepted, and it is proposed to be covered by reed-thatching.”

The gamekeeper’s lodge was not to be not only a home but “a legitimate and favourite embellishment of an estate, and readily becomes an important feature in the park, particularly if placed amidst its wild or romantic scenery; being designed with taste, and the ground allotted to it furnished with shrubs and flowers, very neatly cultivated : here its little garden and lawn opposing the massive forms and deep coloured forest trees and the bold roughnesses of the park, effects a contrast alike unexpected and gratifying.”

There plenty of other extraordinary buildings designed to be ornaments to the landscape as much as residences, including this ecclesiastical looking lodge with its barley-sugar Tudor chimneys. It had to stand out because it was where “the first impression is made on the visitor’s mind when he arrives at the approach,”

You can tell how important that instant appeal had to be because “of less importance is the internal convenience”. Amazingly although Papworth says all the other designs are simply that, just designs, this one is a real building: the lodge at Fulham Palace, the seat of the Bishop of London. Even though this is a series about ornamental gardening the garden is not mentioned once.

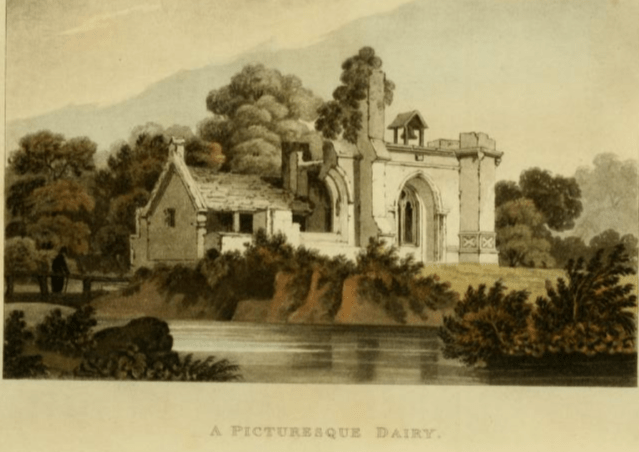

The dairyman or possibly farm manager was well provided for too with a small living space in the sham ruins of the Picturesque Dairy. It was we are told “designed in imitation of the ruins of a church or chapel formerly belonging to a small sequestrated religious establishment” and best placed beside still water in imitation of a monastic fish pond. The outside should bear marks of “the dilapidations of time” whereas the inside – although presumably not the living quarters – should be handsomely furnished in the Gothic style of the 12th century. It should be “surrounded by well-grown plantation, the appearance in consequence would become far more interesting backed by foliage of many-tinted green, occasionally hidden, and then bursting on the sight, which would enrich the homegrounds, and enliven the neighbourhood.”

And if that wasn’t posh enough for the cows then Papworth added another Gothic design for a dairy that should have painted glass windows and be decorated with designs from cathedrals, although its on a smaller scale so doesn’t have any staff accommodation.

Other practical buildings he included in the series were a poultry house, a bath house and an apiary which would more than just a “garden embellishment” because “few studies afford more satisfactory results to persons of leisure and reflection” than watching bees at work.

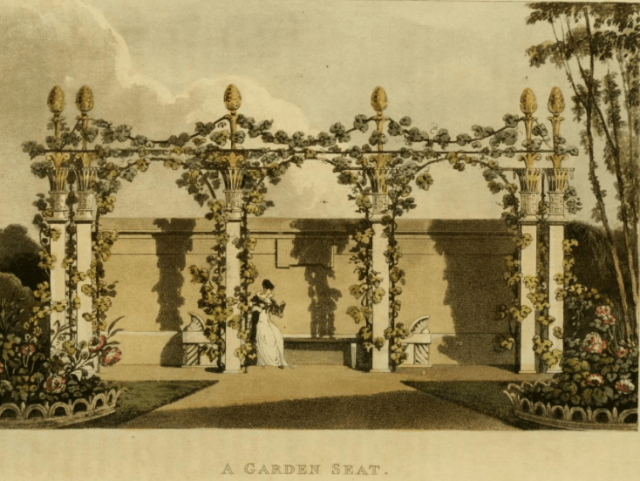

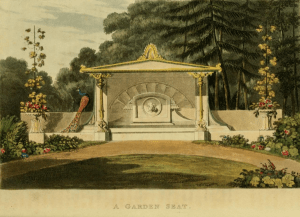

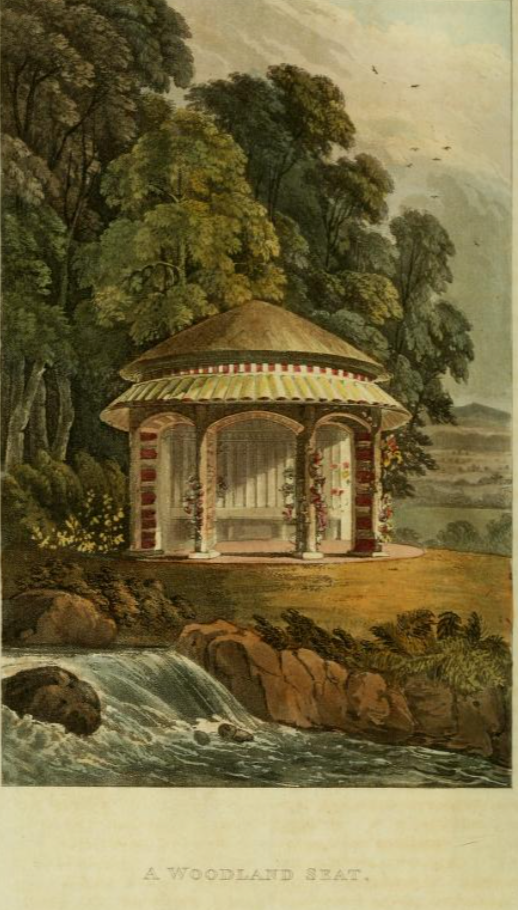

It was not just practical working buildings but also recreational and ornamental ones, including an array of garden seats and shelters. Some were in traditional style like the grand seat on the left, with its large urns at either end designed to contain pots of flowers. Others were less conventional, such as the design below for a rustic Polish Hut [Why Polish? Rather like the Swiss Cottage earlier the connection of the name to the place is a bit bizarre.]

One more strange bit of nomenclature was this tent which had an iron framework intended to be covered with climbing plants and/or have a canvas cover which Papworth suggests should be” orange-colour and white [which] so well harmonize with landscape scenery,” [Says a lot about his colour sense!] Supposedly it was also designed to be easily moveable. But why on earth was this thought to be Venetian?

Garden seats were used to show how taste in garden buildings changed. We are told that once fashionable “rustic seats, bowers, root-houses and heath-houses, and such small buildings, now…very sparingly, decorate our gardens, when propriety would admit something in substitution for them, more corresponding with the character of the place and the scene and more analogous to classic art.”One of those shown was based on Indian architecture, and the other on the tents of army officers, and could be taken down and put away in winter.

Rustic seats may no longer have been in vogue but one was included albeit not primitively so, and nicely ornamented with flowers.

The accompanying article was the beginning of a potted history of garden design, which went on to include pieces about being about “Mr Brown” and his work as well as those “delineations of pictorial beauty, which in the higher classes of landscape art are most particularly engaging : hence the terms picturesque and landscape-gardening”.

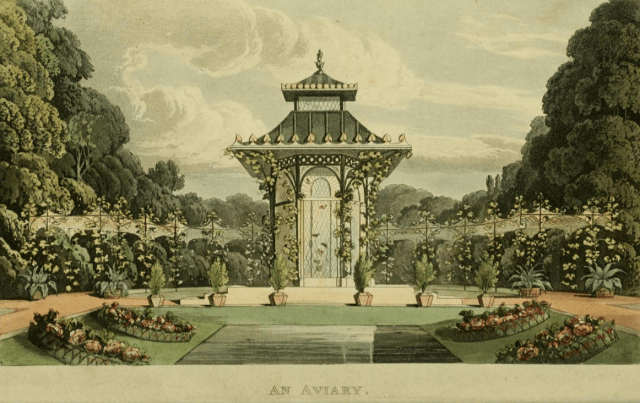

For some reason this was illustrated by an extraordinary almost chinoiserie aviary/kiosk [see below] set in an almost Reptonian flower garden.

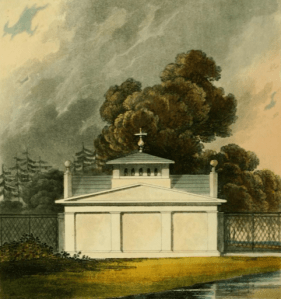

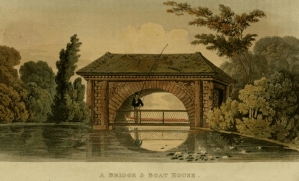

So far Papworth has included almost every architectural style available for his buildings except from “standard” classical. But he hasn’t forgotten it and it crops up in temple form as another aviary, and again a few months later – this time perched on a bridge.

Another classical feature appeared following the death of George III in 1820 in the form of a cenotaph.

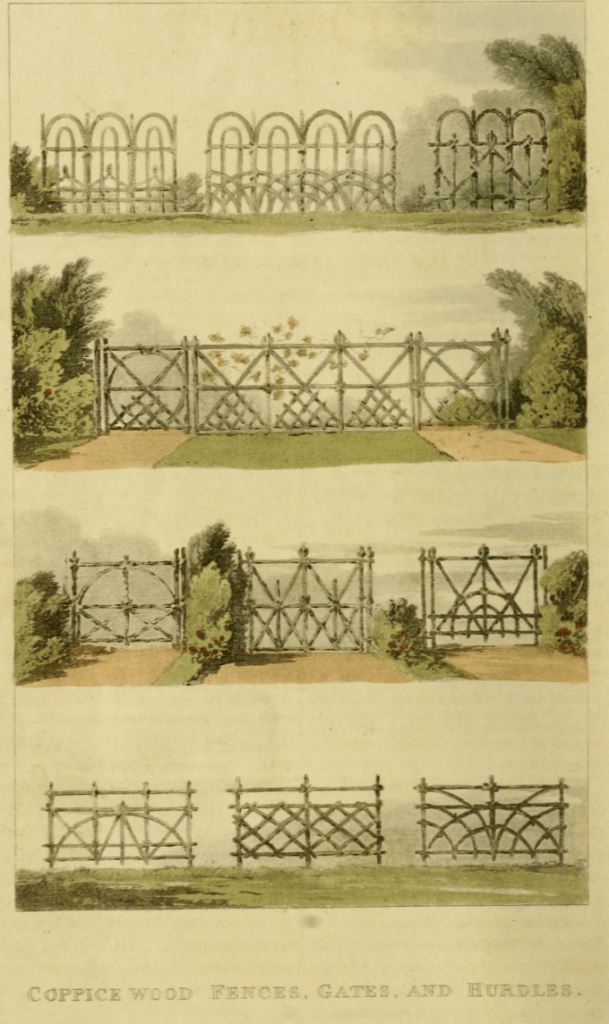

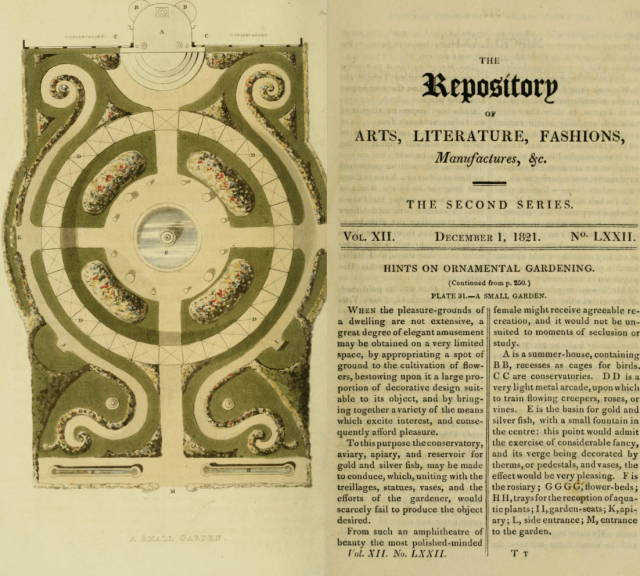

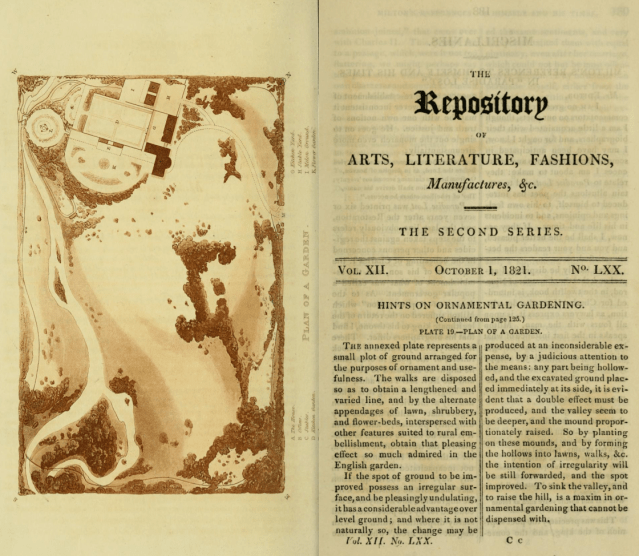

And finally [I’m sure you’ll be pleased to hear] there were designs for bridges, railing, and gates and even a couple of gardens.

The gardening series lasted until the end of 1821 although there were occasionally other articles about horticultural matters. The Repository of Arts itself stopped publication in 1828.

Rudolph Ackermann retired in 1832 and died in 1834. He was buried in the churchyard of St Clements Dane in central London not far from his Repository of the Arts shop. The business passed to his son George who went into partnership with his brothers but it was wound up in 1861when George emigrated to America.

There are lots of references to Ackerman and his Repository online but nothing particularly detailed, so why not take a look at a few issues for yourself, by following the links on one of the images above

You must be logged in to post a comment.