It was The Times that called Anne Pratt “the popular writer on botany” but I suspect to most of us [me included] she’s an unknown & forgotten woman. Yet that’s a bit strange given that she was one of the most well-known botanical writers and illustrators of her day, with 20 books to her credit, and apparently a favourite of Queen Victoria.

Anne merits an entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, but for such an apparently prominent author she’s been quite difficult to track down. Almost everything known about her – including the ODNB entry – comes from an obituary in The Journal of Botany, British and Foreign for July 1894 and even that starts off: “we briefly reported in this Journal the death of this lady who was known to several generations of children…but were then unable to give much information about her.” However they eventually “obtained some particulars of her early life from her niece, Mrs. E. Wells, and a short notice of her work seems desirable”.

So who was Anne Pratt?

Anne was the middle of 3 daughters of Sarah Pratt and her husband Robert, a wholesale grocer from Strood in Kent. She was born in 1806 but seems to have suffered from poor health which rendered her unfit for active pursuits so she devoted herself to more sedate literary study until a family friend noticed ‘her keenness of intellect” and introduced her to botany. She quickly discovered her forte and aided by her elder sister who collected plants for her, started an herbarium. She also made sketches of the living plants to make it more useful. These drawings afterwards formed the basis for illustrations for some of her books.

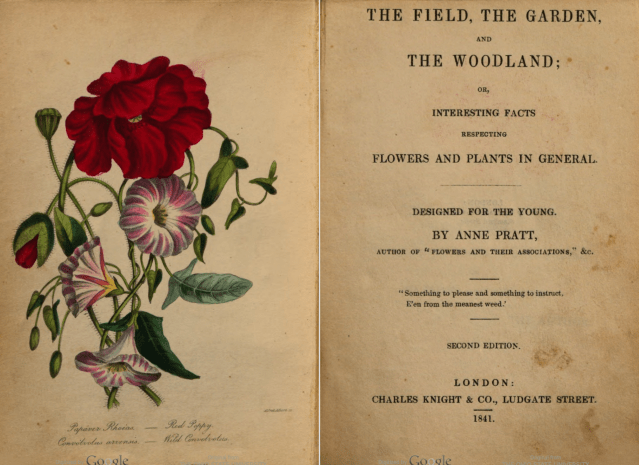

Her father had died when she was 13 and she was bought up by her mother who must have encouraged her to pursue what was seen as her “ladylike” pursuit. Her first book The Field, the Garden, and the Woodland, aimed at children, was apparently written without the knowledge of any of her relatives and was bought out anonymously in 1838. It proved so popular another edition came out in 1841, this time with her named as author, with a third following a few years later.

It covered the range of botany both home and abroad and she aimed “to awaken some interest in the study and observation of nature, a study alike elevating and consoling in its influences on the mind …[and] to direct the attention to the wisdom and goodness of God, as exhibited in the structure and arrangement of the vegetable kingdom.” Lots more in the same vein followed but mixed with historical references that clearly her young audience were expected to understand – although I suspect they’d mean little or nothing to children or even many adults today.

“We can well sympathise with the feelings of the good Izaak Walton, when he said, “When I sat last on this primrose bank, and looked down these meadows, I thought of them as Charles the Emperor did of Florence, that they were too pleasant to be looked on but only on holidays.” Who, you might ask, is Isaak Walton or Charles – and what was he doing in Florence?

After that she changes tack and points out that “The physician views [plants] with a different eye. He regards the flowers as blossoms of plants that shall afford him the means of alleviating suffering.” She also implies that plant hybridisation had become commonplace because “while the botanist beholds before him a field for investigation, the results of which will furnish to himself and others a source of knowledge that may assist in the production of new species of plants” and foreshadowing work that is still going today,” in the discovery of many properties hitherto unknown.””

She was to follow this up in 1852 with The Pictorial Catechism of Botany intended for use with children, which included lists of questions at the end of every chapter for the adult to ask. Like her contemporary Jane Loudon who also write books about plants for children There is no talking down or use of non-technical language to simplify concepts.

She was to follow this up in 1852 with The Pictorial Catechism of Botany intended for use with children, which included lists of questions at the end of every chapter for the adult to ask. Like her contemporary Jane Loudon who also write books about plants for children There is no talking down or use of non-technical language to simplify concepts.

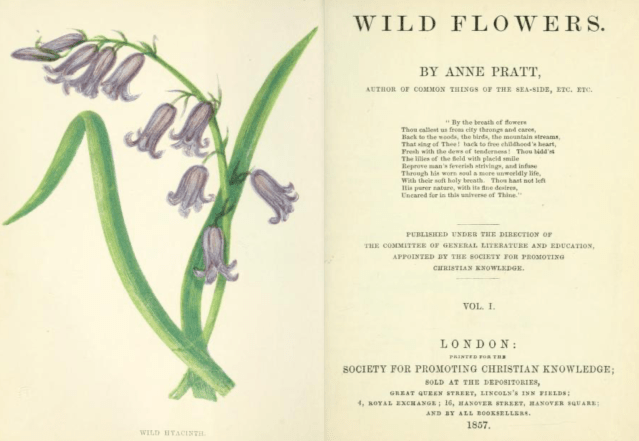

Her Christian faith shines through, often as she says in one preface: ” to point the reader to the connexion existing between the kingdom of nature and the kingdom of heaven.” Certainly she had several of her books published by the Religious Tract Society, or its commercial publishing arm the Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge. The SPCK as it was usually known was a big player in the London scene, not confined to overtly religious subjects.

Unfortunately as her obituary tribute explained ” these religious bodies are notorious offenders in the matter of omitting dates from title-pages it is not easy to say exactly when they appeared. Two very pleasant little volumes— Wild Flowers of the Year and Garden Flowers of the Year—were issued by the latter Society about 1846. Being anonymous, they do not appear under “Pratt (Anne)” in the British Museum Catalogue, where, however,—such are the inscrutable ways of cataloguers !—one is to be found under “Flowers”, the other under “Garden.” Incidentally, they still aren’t attributed to her in the British Library catalogue.

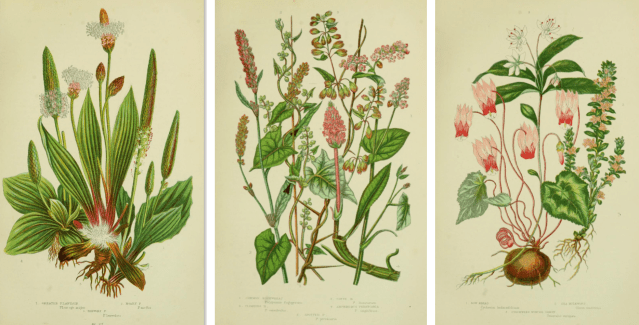

Her first book aimed at adults ,Flowers and their associations, followed 2 years later, in 1840 when she was 34. However this may have been a reissue of a work published anonymously when she was only 20: if so it’s not listed in the British Library catalogue. It included her observations on 30 different flowers and was written in what was then seen as a very accessible style, but also included extracts from her own poetry as well as from Keats, Milton, Wordsworth and others. There were chapters about 30 flowers from meadow plants such as buttercups and pimpernels to comparatively exotic flowers such as passion flower and myrtles. The illustrations in the most vivid colours were printed using the recently invented chromolithograph process. Unfortunately and rather strangely the only on-line version I can find is in black and white hence the image from a bookseller’s website where a copy is/was available for £55.

After her mother died in 1845 she went to live with friends at Brixton where she continued to write and paint before eventually settling at Dover in 1849. It was there that she finished writing The Ferns of Great Britain, published in 1850. Ferns were the subject of a collecting mania in the mid-19th century [ see this earlier post for more information] and were to be a subject she was to return to several more times.

The same year SPCK also published Chapters on the common things of the sea-side which included notes not just on plants, but birds, and sea-life of all kinds all from her own observations.

It was followed in 1852 and 1853 by the two volume Wild Flowers, which again used her own bold but simple and effective paintings of the various plants included. The text too was short and simple with two pages allocated to each of the species selected, although she also included a note of their place in Linnaean orders and classes as well as what she called natural orders. Reprinted several times it was proved popular with children perhaps because it was also issued in sheets for hanging up in school classrooms. In 1940 The Bookseller reviewed a reissue as ” a new cheaper edition of this finely illustrated, delightfully written and informative book” Yours for just 5 shillings.

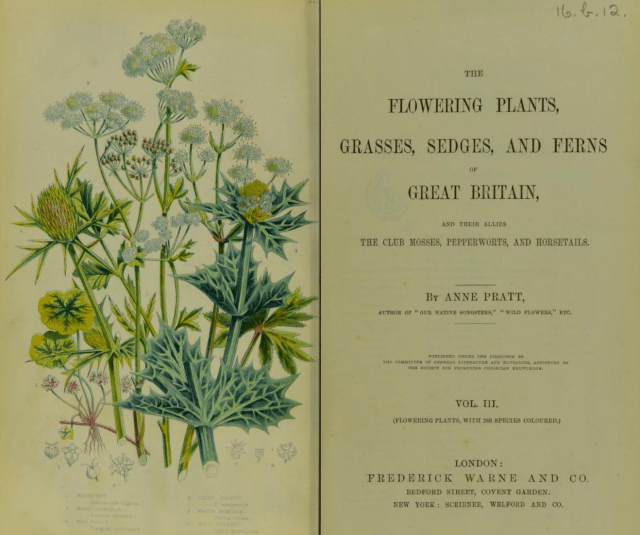

Now she became more ambitious and embarked on a huge project to produce a comprehensive work about The Flowering Plants of Great Britain This came out in 5 volumes from 1855 onwards with a sixth later appearing in 1873, when the earlier ones were reprinted in a uniform series. This was probably outside the scope of SPCK and instead was published by Frederick Warne, who also published Beatrix Potter.

Now she became more ambitious and embarked on a huge project to produce a comprehensive work about The Flowering Plants of Great Britain This came out in 5 volumes from 1855 onwards with a sixth later appearing in 1873, when the earlier ones were reprinted in a uniform series. This was probably outside the scope of SPCK and instead was published by Frederick Warne, who also published Beatrix Potter.

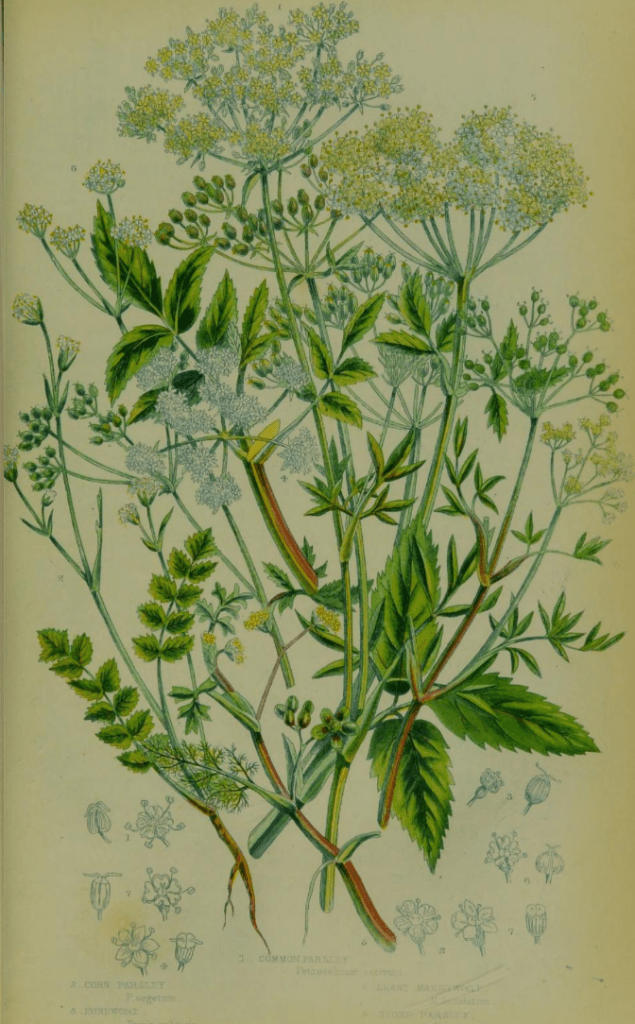

The text is now much more detailed and scientific in approach, and covered more than 1500 species. The 300 or so illustrations were also of much higher quality. This is almost certainly because she worked with William Dickes a leading engraver and chromolithographer . who used the more affordable Baxter method of chromolithography, which allowed her work to reach a wider audience.

It was to become one of the standard 19thc reference books on British Flora and when the copyright expired in 1879 Frederick Warne her publisher bought it and the following year “with her characteristic vivacity revised it.” He then reissued it in a cheaper form which made them both a lot of money. Warne reissued the series again in 1905. Apparently her images of ferns were even re-used, although in black and white rather than colour, in the Observer’s Book of Ferns published in 1950.

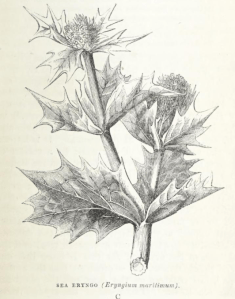

Alongside this encyclopaedic series she continued to produced shorter more accessible works in simple language aimed at a more general reader, and/or children. Amongst them were Poisonous, noxious, and suspected plants, of our fields and woods , which had a half page` illustration matched by half page of text; Our Native Songsters about birds; The British Grasses and Sedges; and in 1863 her final book Haunts of the Wild Flowers.

But as was often the case with female botanical illustrators of the era, particularly self-taught ones like Pratt, her work was criticised for apparently not being scientific or accurate enough, although her strengths were also recognised.

James Britten the editor of the Journal of Botany who wrote her obituary notice , for example says of the 6 volume Flowering Plants : “Botanically it is a weak book, but as a popular account of our wild plants it is still the best we have, and the coloured illustrations, in which allied plants are grouped together, are not umpleasing, although not likely to be of use to the critical botanist… The drawings both in this and the earlier work were, I believe, prepared by Miss Pratt; those in Wild Flowers show far greater originality, the Flowering Plants being manifestly indebted to English Botany in many instances.” [There are two major works called English Botany – one by James Edward Smith, founder of the Linnaean Society and published in parts between 1790 and 1811 and the other, which is the one I suspect he is referring to by James Sowerby which came out in 1863.]. Elsewhere Britten insisted her work was “meagre and incomplete.. and lacked the scientific credentials to grant her the appellation botanist.”

Later Wilfred Blunt’s Art of Botanical Illustration argued the plates in Flowering Plants were “pleasantly composed though owing to the popular technique of chromolithography not very accurate in colour…”

Despite these criticisms, Anne clearly had a vast botanical knowledge, and was more successful than most of her female contemporaries. She was even given a grant from the Civil List, perhaps on the suggestion of Queen Victoria who was apparently a great admirer.

Her work was financially successful too, and although she may have inherited some money it seems her books were her main source of income until in 1866 at the age of 60 she married John Peerless, a wealthy man from East Grinstead living on property and investments.

Anne died on 27 July 1893 aged 87 years old. There were obituaries in newspaper the length and breadth of the country – although to be fair most are pretty similar as if taken from a press release, perhaps by Frederick Warne. The comments were however much more charitable than Britten, calling her “a devoted student of nature, accurate and painstaking in all her researches, she was also gifted as na artist.” and I’m sure to Britten’s annoyance calling her not only “a popular botanist” but also a “distinguished” one.

For more information although there are several other blog posts about Anne, most quite similar but if you want to read more I’d suggest Geoff Rambler’s Weird and Wonderful Kent site, and The Tale of Anne and Beatrix from the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh.

You must be logged in to post a comment.