A few month ago I wrote about the Botanical Gardens at Ooty in southern India where the first superintendent was a Kew-trained gardener, William McIvor. He arrived there in 1848 and spent the rest of his life in Ooty running the gardens

While that was an impressive achievement he became much more famous in his own lifetime for his work growing cinchona – which was to be “the commodity which changed the world.”

If you haven’t heard of cinchona you’ll definitely have heard of the product which is derived from its bark and, if you’re old enough, may even have benefited from it yourself if you’ve ever travelled to the tropics.

Unfortunately his story doesn’t end that well and he died a disappointed man on June 8th 149 years ago.

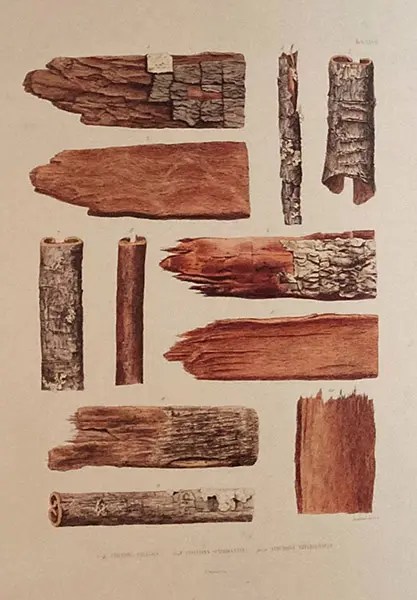

The bark of the cinchona tree is the source of quinine, although there are, according to Kew, 24 species of cinchona all native to western South America. and not all of them yield the same quantity or quality of quinine.

Given the wealth of pharmaceuticals the world now enjoys you might not realise that quinine is the one which has probably benefited more people than any other because it was until recently the main treatment for dealing with malaria.

Malaria was, and indeed still is, a serious health problem, killing between 150 to 300 million people in the 20th Century. According to World Health Organisation, nearly half of the world’s population live in areas where the disease is still transmitted.

Nowadays we know malaria is caused by a parasite carried by female mosquitos, but in the past it was thought to be caused by pestilential fumes arising from swamps – literally from “bad air”. In Britain the disease was know as ague and was a major cause of death especially for young children. [For more on this see Paul Reiter’s article From Shakespeare to Defoe: Malaria in England in the Little Ice Age]

Malaria was also a major cause of death amongst Europeans in the tropics and sub-tropics. Just a few minutes wandering round the graveyard of the church at Ooty showed just how many British soldiers and colonists died young in India in the 19th century of tropical diseases of which malaria was the easiest to catch.

Mortality rates were so serious that once quinine was available to prevent, or at least seriously mitigate, the effects of malaria it was possible for European powers to undertake much greater colonial expansion. Quinine was certainly given as a precaution to the armies of the Dutch in Indonesia, the French in Algeria, and the British in Jamaica, West Africa and South-East Asia as well as India.

For more on the link between quinine and colonialism a good place to start is Daniel R. Headrick’s “The Tools of Imperialism” in The Journal of Modern History 1979

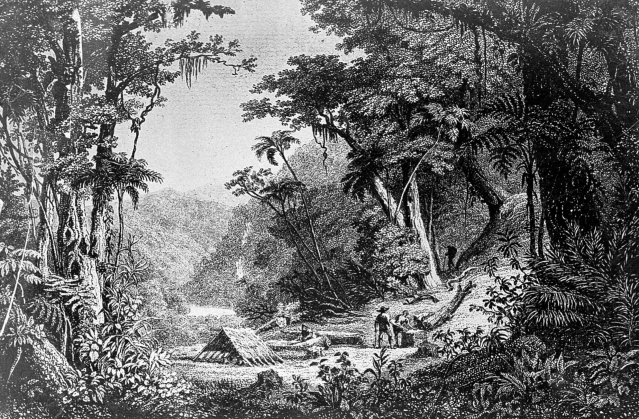

Of course the medical properties of the bark of the cinchona tree – sometimes known as the Andean fever tree – had long been known about by the indigenous people in Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia where it grows high in the cloud forests of the Eastern Andes. However, there are no mosquitos there, and it’s hundreds of miles from the coastal swamps where they thrive. So how did anyone discover its power over malaria?

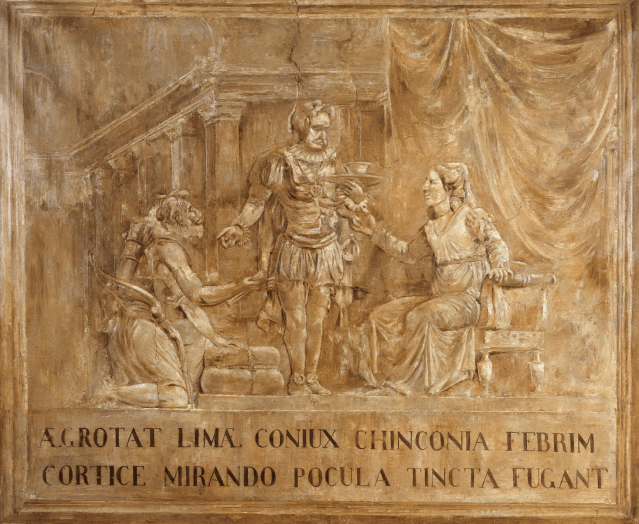

There are several stories about how this happened – none of them verifiable. The most well-known one tells of the illness of the Countess of Cinchon, the wife of an early Spanish viceroy of Peru, and her cure by a concoction of the bark administered by Jesuit priests who had obviously learned of its potential from indigenous healers. Despite the fact that the tree has been named after her [or him] the story been fairly conclusively disproved. Nevertheless by the mid-17thc the bark was being imported to Europe, as “Jesuit’s powder” although that name led to prejudice against its use in staunchly Protestant countries.

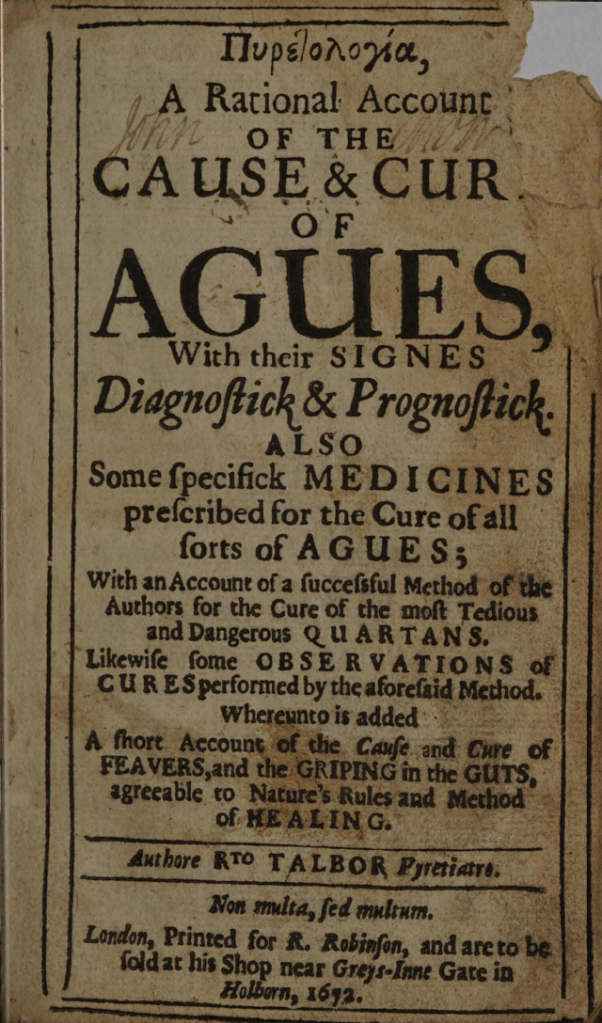

The breakthrough came when Charles II was cured of an ague by Robert Talbor using the bark. Talbot wrote up his remedy Pyretologia: a Rational Account of the Cause and Cures of Agues, was ,made Physician Royal in 1672, knighted I 1678 and then travelled round Europe becoming famous for curing Louis XIV, Queen Louisa Maria of Spain, and many other royal and aristocratic patients.

The breakthrough came when Charles II was cured of an ague by Robert Talbor using the bark. Talbot wrote up his remedy Pyretologia: a Rational Account of the Cause and Cures of Agues, was ,made Physician Royal in 1672, knighted I 1678 and then travelled round Europe becoming famous for curing Louis XIV, Queen Louisa Maria of Spain, and many other royal and aristocratic patients.

Until the 19th century, South America was still the only source of cinchona and as demand increased so the forests where the cinchona trees grew were cut down and supply started to dry up. Now European powers, recognising its economic and health importance decided to try to obtain plants or seeds to grow them in their colonies.

With the Spanish empire in South America breaking up, the newly independent countries such as Peru tried to outlaw the export of cinchona plants and seeds. Of course this didn’t stop people trying by legal or illegal means. French, Dutch and British expeditions tried to collect cinchona, not always with much success but in 1852 Justus Hasskarl, working for the Dutch government, managed to send seeds back to Holland where they were germinated and the plants sent to the botanic garden at Buitenzorg (now known as Bogor) on Java by where quinine extraction began a couple of years later.

For more on these early expeditions a good place to start is Clements Markham’s Peruvian bark : a popular account of the introduction of Chinchona cultivation into British India, 1880

The British government’s efforts were led by Clements Markham, Geographer to the Foreign Office, who had already spent a couple of years travelling in Peru. Discussions had obviously taken place about where in the colonies the cinchona should be sent and two areas were chosen: the hills of central Sri Lanka and the Nilgiri Hills around Ooty.

Markham had already met William McIvor and said the gardener had “long taken a deep interest in the question of the introduction of chinchona-plants into India, and brought the subject to the notice of Lord Harris, then Governor of Madras, as long ago as 1855. Since that time he has made himself master of the subject by a study of every work of any importance which has appeared in Europe within the last thirty years” The two men must have been in touch again before Markham set off back to Peru in 1859 because the following year he was ready send back not only seeds but plants of two species Cinchona calisaya. and C. succirubra, (now C. pubescens) . These were sent in Wardian cases specially adapted following advice from McIvor.

For details of the transport methods and the adapted Wardian case see Chapter 20 of Markham’s Travels

In Sri Lanka the first plants went in at Hakgala, which is an elevation of about 5000 ft and a cool temperate climate. The first harvest there was in 1870, with 500 acres under cultivation by 1872 and 64,000 acres by 1883. Exports reached 16 million pounds weight in 1887 but as cultivation spread elsewhere in the tropics it led to a drop in the price through overproduction. Later Hakgala became an experimental plantation for tea and then in 1881 a botanic garden which it remains to this day.

McIvor’s first consignment of cinchona seeds reached at Ootacamund in January 1861, and he followed the methods used by the Dutch at Buitenzorg. However germination was poor, and for later sowings he experimented with different soil mixes with much more success. The plants in Wardian cases arrived that April – 463 plants of C. succirubra and 6 of C. Calisaya all in very good condition. The new arrivals were put under glass, germination rates improved and propagation by layering and cuttings increased the number of plants rapidly. By June 1861 there were 2114 and by January 1862 as many as 9732.

In July 1861 McIvor was appointed Superintendent of Chinchona Cultivation “with full and entire control over the operations, in direct communication with the Government, and subject to no interference from any intermediate authority.” It was also agreed to build a new propagating house for cinchona capable of holding 8000 plants. McIvor now drew up detailed instructions and advice for future cinchona plantations elsewhere in India. So it’s not surprising that Markham said McIvor “united zeal, intelligence, and skill to the talent and experience of an excellent practical gardener”.

For more technical details on growing and propagating cinchona see Chapter 28 of Markham’s Travels and WilliamMcIvor’s Report of Cultivation

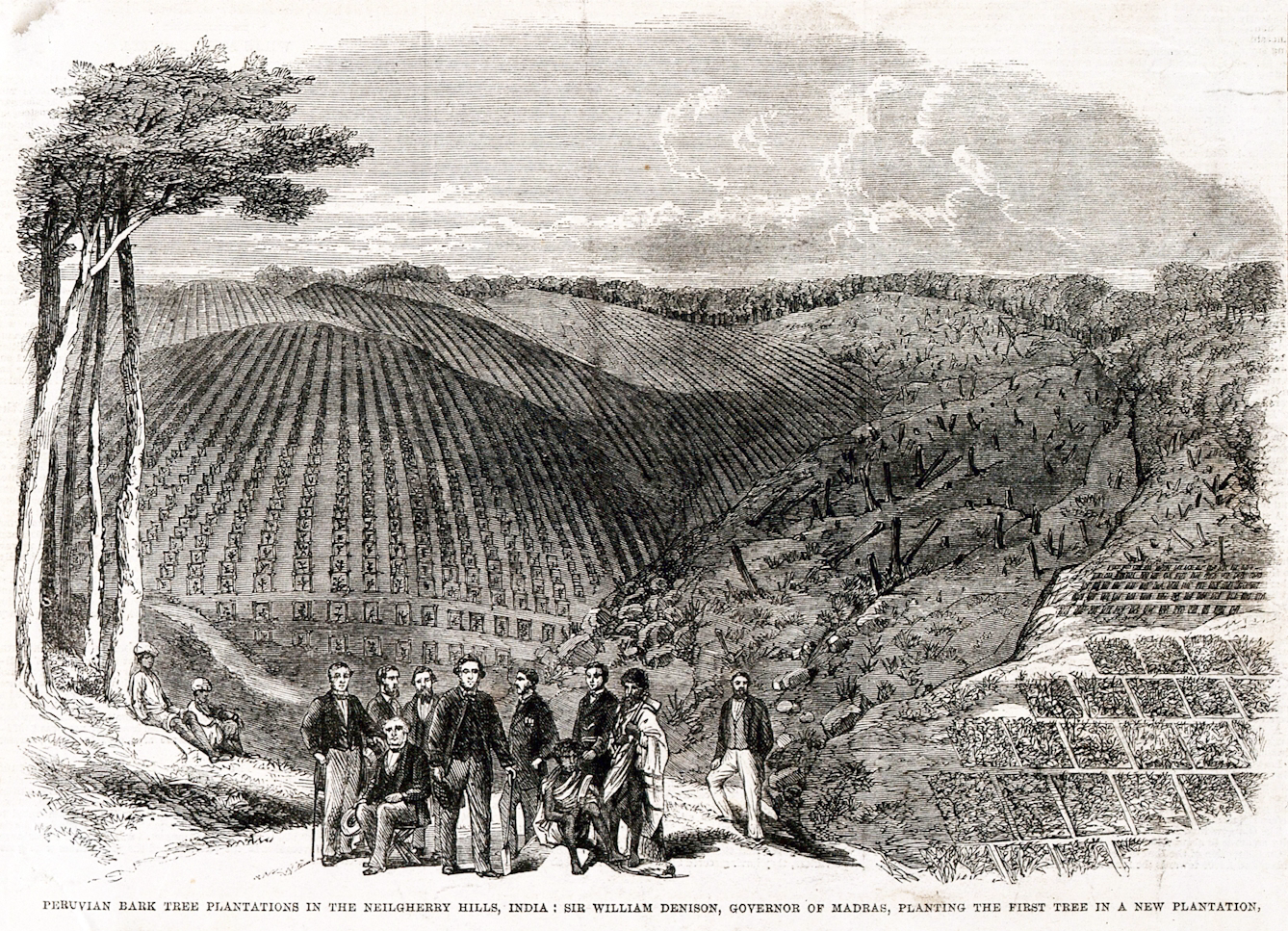

When the cinchona trees were of a suitable size for transplanting into open ground McIvor chose land on the slopes of the highest local peak – Doddabetta – some 6800 ft up and 17 miles from Ooty. The new venture was considered so important that the first trees were planted by the Governor of Madras, Sir William Denison, on the 30th August 1862 and even reported in the Illustrated London News. McIvor himself moved out to Doddabetta so that he was on site to deal with any problems and to oversee trials of different growing conditions and techniques.

For more on the site and its advantages etc see Chapter 23 of Markham’s Travels.

McIvor became the British empire’s leading expert of growing cinchona. He was able to send consignments of plants to the government gardens at other hill stations – with notable success at Darjeeling – as well as to private growers all round the Nilgiris. By January 1863 he was offering young trees for sale although it was a long term investment because the trees need to be about ten years before they could be harvested. Nevertheless there was considerable take up by experienced planters of other crops , notably coffee, which thrived in the Nilgiris. They could see the huge imperial benefits – and personal profits – that would be obtained once quinine could be produced locally.

McIvor himself invested in some of these ventures, By the end of 1866 there were as many as 30 plantations in the Nilgiri Hills with McIvor reporting a total of 1,785,303 plants under cultivation. By 1871 the government had 1200 acres of cinchona plantation of its own plus all the private growers and regular consignments of bark were being sent to be marketed in London, although it didn’t match the quality of South American cinchona.

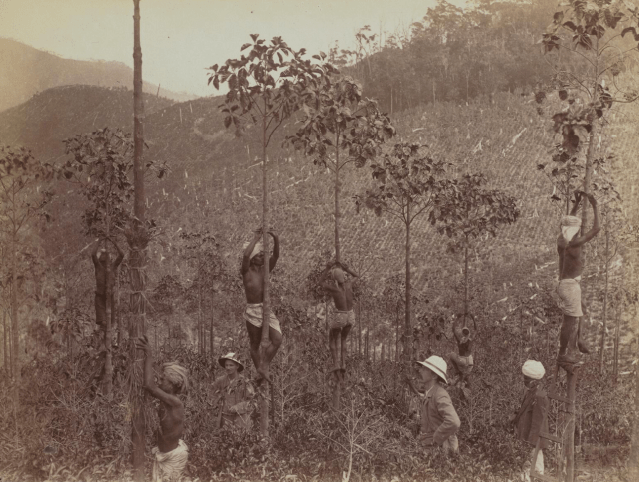

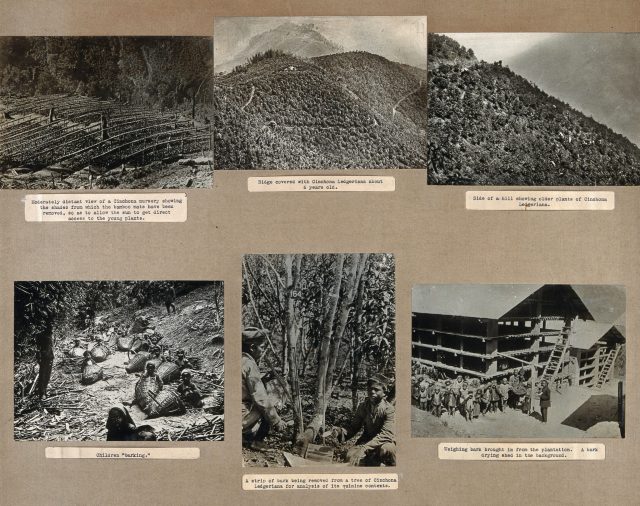

Now things began to turn to a scientific analysis of the crop. A specialist quinologist, John Broughton , was appointed to work at Ooty to test, extract and improve the quality of the quinine. Harvesting bark is a skilled task and very labour intensive, especially as there are several gradations of bark with the general rule being that the thicker the bark the greater the quinine content. There were debates, not always that cordial, about how to increase quinine yield.

McIvor initially planned to carry out an annual programme of harvesting by encouraging the trees to branch as low down as possible and then remove alternate branches each year which would encourage the tree to produce fresh growth. Unfortunately the bark that was produced by side branches and small shoots was thin and known as quill bark, and crucially this has less quinine content. Much better was the thicker bark from larger branches or the trunk itself. For that reason John Broughton favoured regular coppicing, but harvesting the trunk was something that could only be done every ten years or so, so this did not produce sufficient quinine. As a result the government ordered him to abandon the idea. He refused, resigned and left India.

It was now back to McIvor who came up with the idea of tricking the trees into producing thicker bark by. removing strips of bark and then wrapping moss around the wounded section which resulted in the tree regenerating much thicker bark there rather like a scab. This process known as “mossing” worked well. The trees recovered and the value of the thicker bark when it was eventually harvested matched that from South America. As Markham said Mr McIvor’s “care has now been fully rewarded, and the experiment has reached a point which places it beyond the possibility of ultimate failure.”

This was good news but it gave rise to a major disagreement. Because now Nilgiri bark was fetching good prices on the London market McIvor tried to cash in and patent the mossing technique. He claimed that the government may have appointed him superintendent of the cinchona plantations but they didn’t own his horticultural or scientific expertise. It was that, he said, which had enabled him to conduct a range of experiments to invent the mossing technique ‘render this great natural process entirely subservient to my will’.

Unsurprisingly Government officials disagreed. They claimed that Mossing was simply a natural process that he had not invented. They then argued that he didn’t really have a leg to stand on anyway: “Prejudice to the public would be caused by enabling a public servant, employed for the special purpose of increasing and cheapening the supply to the public of a rare and costly drug, to use the information and experience which he had acquired in the public service and at the public cost for his individual benefit and to the public detriment, by making his charge for the use of his patent an element in the market price of the medicine, and tending to restrict the use of the medicine by adding to its cost.”

McIvor responded angrily in 1875 that ‘the promulgation of this discovery [mossing] in 1866, raised against me a storm of opposition, which has blighted my prospects ever since.’ He signs off ominously, ‘I feel that this is probably the last exertion I may be able to make in the interests of an undertaking, in which I have laboured so zealously and to which I have devoted the best years of my life.’

Those were ominous words indeed because he died a few months later on June 8th 1876, leaving the Nilgiri plantations, and the south Indian cinchona industry without a Superintendent.

While McIvor and his employers were bickering private planting flourished. The South of India Observer noted in May 1877 that, after a slow start, ‘everybody is going in for this cultivation.” A quinine manufactory came into production in the 1880s and by 1890 packets of medicinal quality quinine sulphate could be bought via local government offices. Unfortunately the good times didn’t last. The ten year harvesting cycle was hard and for small scale planters difficult to support, especially as other crops such as tea offered speedier returns. It is of course tea and to a lesser extent coffee which dominate the Nilgiri hills today.

McIvor wasn’t replaced until 1883 when the Professor of Botany at Oxford, Marmaduke Lawson was appointed “Director of Government Cinchona Plantations, Parks, and Gardens, Nilgiris”. One of his first tasks was to carry out a comprehensive survey which. found that there now only 569,031 trees, only a fraction of the number reported by McIvor which begs the question did McIvor exaggerated his success? Or had the intervening period of neglect taken a severe toll? Certainly it seemed that the cinchona experiment at Ooty was in decline, and although Sri Lanka’s was a little longer lasting, by the 1890s the Dutch plantations in what is now Indonesia dominated the trade globally. This was largelybecause of the introduction of a much higher quinine-yielding variety Cinchona ledgeriana to Java. Quinine was finally challenged and then superseded in the 1970s by artemisinin, a drug derived from wormwood, as the world’s go-to malaria remedy but I’m sure McIvor wo0ud have been a whizz at growing that too!

For more information, apart from the various links above, good places to start are The BBC’s webpage The tree that changed the world map; Cambridge University Library’s Cinchona: a short history and the short video on the Kew website.

Red cinchona, c.pubescens (c) Mario Cuervo CC BY-NC 4.0

You must be logged in to post a comment.