“At 12 o’clock, Saturday May 26th 1792, I had taken the Paddington Road, which the rains of last night had made nice riding, and the face of nature gay” So begins the account by Colonel the Honourable John Byng. of his journey from London to explore the sites on the road to Yorkshire.

So what, you might think. After all Byng was just the younger son of a not-very-well-known aristocratic family, who followed the normal career path for younger sons, choosing the army over the navy or church and ending up as a tax official. In the last few weeks of his life he inherited his brother’s title and became Viscount Torrington, but none of this is the stuff of great novels or an obvious way to get written about on The Garden History Blog.

However, John Byng was also a great traveller and better still a great diarist, and he kept a detailed account of his many tours around Britain. His journals are often sharp, acerbic and amusing [if only by default] and from them we get an 18thc gentleman’s insights into the British landscape, its great houses and gardens and much more…including on this trip a less than flattering account of Humphry Repton.

Byng’s ride from the Paddington Road soon bought him to one of the great estates of Georgian Britain, although one severely altered since its heyday. “Beyond Edgware are what remains of Cannons Park, and House; a wonderful change from a Dukedom to the present possessor!” Built for James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos, who had made an immense fortune as Paymaster General to the Forces, Cannons was by all accounts one of the most magnificent houses in the country. Unfortunately Chandos was so extravagant that on his death in 1744 his son was obliged to sell off everything and the mansion was demolished less than 30 years after its completion. Byng observed sharply: “then ‘each parterre a lawn’ now each parterre a potatoe ground! Trade and gambling overset all distinctions.”

For more on Canons see the website of the Friends of Canons Park

Byng was not only interested in grand estates but he was also a connoisseur of inns, recording in great detail what he ate, usually what his bed was like and how much everything costs. It was at the Sun Inn in Biggleswade in Bedfordshire a couple of days into journey that after breakfast when was about to leave to visit friends when “Mr Repton — the now noted landscape gardener — came in, and delay’d me for an hour.”

I’ve always thought of Humphry Repton as an amiable if somewhat ingratiating character but Byng thought him as rather more annoying. “He is a gentleman I have long known, and of so many words that he is not easily shaken off; he asserts so much, and assumes so much, as to make me irritable, for he is one (of the many) who is never wrong ; and therefore why debate with him?”

Byng eventually got away but that evening “at 9 o’clock Mr R return’d from his visitation in this neighbourhood; to draw his plans, and to relate his journies, his consequence, and his correspondence. Scarcely any man who acquires a hasty fortune, but becomes vain, and consequentional; tho’ Mr R — being now sought for, has a professional right to dictate, and controul ; and being Nature’s physician, to tap, bleed and scarify her. But he is very wrong (in my opinion) in not being well mounted; and in not building a comfortable travelling chaise with a good cave for Madeira wine. But to all this R — is a Stranger; and -piques himself upon sleeping in fresh sheets every night (!) which hereafter he will dolefully repent. Having much discourse (for R — is an everlasting talker) we did not part till midnight.”

Underway at last, Byng passes Waresley Park in Huntingdonshire, “one of those to be improved by Mr R”. [The Red Book, commissioned by owner William Needham, is in the Lindley Library but has not been digitised.] “All the country around is newly enclosed; which Capability R[epton] at Biggleswade said ‘was a fine invention and a noble thing, for in Norfolk they allotted to each cottager an acre of land. . ‘Noble, and useful indeed’, answer’d I, ‘to give to a man an acre of land, which he may sell away in an hour, in lieu of that permanency, which our ancestors (under the guidance of Providence) alloted for a perpetuity’. As he proceeds there are several more strong words about the evils of both enclosure and industrialisation both of which led to rural depopulation, and turned country labourers into “mean drunken wretches”.

Nor was Repton the only famous name to come in for criticism. When Byng reached York he obviously visited the Minster but was horrified when he saw the floor, where “the pavement pattern was the invention of (that great architect) Lord Burlington and might be invented by a school boy for his kite.”…

Thence I went to view the Assembly Room built from a plan of Ld. Burlington’s: who was surely the most tasteless Vitruvius.? and has left the saddest Egyptian Halls, and woeful walls to record his invention !”

When we today visit stately homes and gardens we do so by checking opening times and by buying a ticket. Byng didn’t often have such restrictions. He can, and does, visit the estates he passes without a by your leave, often riding the grounds and passing quite sharp comments on their state and what improvements need to be made to make them acceptable. For example he visits the Earl of Gainsborough’s seat, Exton Park in Rutland: “the outskirts are farmed off, but it is not a very large Park, without beauty, or keeping.”

The earl was fond of mock naval battles on his lake and built Fort Henry a gothic folly on the shore as part of the fun. Byng was having none of “these strange buildings, and absurd inventions … which shou’d be pull’d down.” And while “the pools are handsome … their banks are not planted.” Amazingly he says he” wander’d about this park for a long hour; not meeting one creature!”

Later, at Ferrybridge in Yorkshire : “I took the high road to the hill top; then turn’d to the right into Byram Park, Sr. John Ransden’s, about which, and around the pleasure ground, I rode at my leisure: it is a verdant, well-wooded place, with a goodish house, and an extent of made water. But the timber, and the shade are the beauties; and rare ones they soon will be.”

Likewise at Wetherby “Having order’d supper, I walk’d into Mr Thompson’s grounds, whose charm is the River Wharf, that foams its wide stream betwixt wooded banks ; but is so screen’d from the house, and grounds, as to afford no sight to them!… but the night coming on hurried me back; with a determination to make an early survey”. The next morning at 7 o’clock, he returned only to discover “the grounds are idly neglected. All these rivers should be lifted up by masses of rocks thrown in; which would deepen, and shew the stream, increase the murmur, and preserve the fish: now they glide away, unheard, and next.”

I suspect part of his reason for heading north was to see sublime and picturesque scenery. His liking for it becomes obvious as the journey proceeds. At Knaresborough he “walk’d up to Coghill Hall, apparently a good house, with surrounding picturesque scenery, and in front the River Nidd, wide, shallow, and brawling. This would be a sweet place, if quietly situated ; but as it is placed close to a town, and in everlasting gape from Harrogate, I do not envy the possessor.” Once again he has strong feelings about what should be done “the water should be much impeded; the buildings to the right of the house removed ; and much of the town of Knaresborough thickly planted off.

Accessing parks, gardens and other places of interest wasn’t always as easy as these examples suggest. There was an “old deserted mansion, call’d New Hall” near Pontefract which … being quite block’d up, I could not get into it.” Similarly he had problems trying to visit the remains of Jervaulx Abbey where there was ” much for the observation to an antiquary; but all the doorways being stoned up, I had to climb over walls, and force my way thro’ nettles, and brambles.”

Sometimes he was told by the landlord of the inn where he was staying that there was a key to a property – or, as he discovered there was supposed to be a key. To visit Bolton Hall he was “directed to a single house, where the key was kept; but unluckily there was no place within; the first gate that we found lock’d — we contriv’d to pass beyond by scrambling over an hedge; but the second, leading into the woods, was not to be forced, neither were the pales to be surmounted.” In nAy case “Bolton Hall is a gloomy, deserted, seat of the Duke of Bolton, all in wild neglect, and, disorder; — which some few years will levell with the ground”. You can almost hear him saying Good Riddance! Luckily, although the Hall was largely destroyed by fire in 1902, it has been rebuilt and is in good shape along with its late 17thc gardens.

For more on Bolton Hall see the excellent detailed history by Val Hepworth for the Yorkshire Gardens Trust

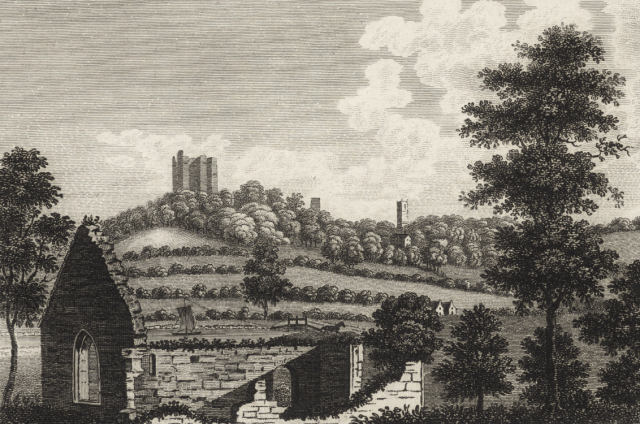

He also wanted to visit mediaeval Conisbrough Castle. “After much hunt, and some vexation, I did find the castle key at a public house; but the publican did not deign to accompany me; and with difficulty I got an old man to hold my horse: so I went up to it alone… An old castle in a wood; and thro’ the grove frequent peeps at the stream: ‘What can be finer? It belongs to the Duke of Leeds, who has done more than most Dukes would do, for he has secured by a strong door the lofty castle, and has repair’d the steps and railway leading to it, of which I had the key. — But as I often say, and must repeat. Why not build a guardian cottage; print a book for them; and let them make their fortune?” From the top he admired the view ” so very beautiful, and romantic, I sat myself down, several times, in the pleasing contemplation.” Often he did more than contemplate but indulged in the fashionable pastime of sketching.

Sometimes however he did encounter owners, tenants or their staff. This was not always that pleasant an experience. For example he viewed “the noble ruins of Bolton Castle” from the outside then “enter’d by the staircase into the rooms ” which he discovered were “inhabited by the families of two farmers; and from one, a surly peasant, did get permission to see these miserable chambers, once the residence of the unfortunate Mary [Queen of Scots]” although “a maid servant attended me about the Castle, for the farmer was too great a man to be disturb’d.”

He rode over from Knaresborough ” to view Plumpton Gardens, belonging to Ld. Harewood; which the gardener ushed’r me… This being only 4 miles distant from Harrogate, must be a delightful saunter of love, or retirement, from that place; for it is a charming spot and of much simplicity, where the water and rocks are drawn into the happiest alliance…. This was a pleasant half hour.”

Plumpton Rocks is a man-made lake and surrounding pleasure gardens in the grounds of Plompton Hall. The gardens were designed by Daniel Lascelles of Harewood in the mid-18th century and were already on a tourist and artists trail even by then, and e Turner sketched and painted there just a few years after Byng’s visit.

Plumpton shows he did have a softer side, and a few other places also seemed to meet with more of his approval – or at least partial approval: ” Scriven Hall, the ancient residence of the Slingsbys, a rare old family, who have (idly) sold the borough to the Dukes of Devonshire, and the Living to Ld. Loughborough. This is a green, well-planted place, with a good house, which to the left commands a noble view; infinitely preferable to a stare in front.”

Even better was Easby Abbey, near Richmond: “There cannot be a more complete a more perfect ruin: about every part of it did I crawl …How romantic, … It is view’d by me now, a petty antiquary, in its great beauty of decay, … there cannot be a nicer ruin.”But criticism was much more common for all sorts of failings. Near Exton “Sr. W. L. has been permitted to cut Ridings! That he should not do in the woods, as it much assists the poacher; chills the timber; and gives a very unfair advantage over the fox, who is to be view’d and halloo’d at every turning; but I suppose it is rights being the high fashion”.

Later he climbed Grantham Hill which had an extensive view but “all wide views are horrors to me; like an embarkment into Eternity. Sir J. Thorolds new house upon a hill top, commands all this vale, staring around in vain for beauties !” This was I think Syston Hall built around 1760 for Thorold who was Minister for the Colonies. It was demolished in the 1920s.

Equally tasteless in Byng’s eyes was Blyth Hall in Nottinghamshire, the seat of the Mellish family. While “The approach… is very bonny, from the beauties of the mill, the enlarged water, and the backing woods…[but] it seems to be a bad house, and the taste around is execrable; the new-built stables appear to most advantage; the water is of quantity, and transparency, but it wants shade; so does the bridge, and the whole place; and the town and stables should be planted off.”

Worse still was Crag Hall near Knaresborough “hewn out of the rock without either taste or design ; then.to Sir Robert’s Cave (of this curious description) scooped out of the rock; with this figure of a Knight-Templar, guarding the door. …The only thing in character here is an old ivytree covering much of the front. Within it is filthy, and with out there is a little dirty flower garden, instead of a gloomy thicket of trees !” The cave was actually home to a genuine hermit, Saint Robert of Knaresborough in the late 12th and early 13th centuries.

“Bolton Park too was dismissed curtly as “a poor, miserable, dismantled park, for the timber is gone, and the few remaining deer seem to be starving” I wonder if it was any better than the house at Retford “of Mr E — (an officer of our office), a neat well-built box; adorn’d, and planked in the true Cockney taste.” Yet when he reached Ripley near Harrogate ,” where is an old seat, the Hall of Sir John Inglebys” [for more on Ripley Castle see this earlier post] it “did not seem to be worth the stopping at.” This may have been because Sir John was in the process of demolishing most of the medieval castle and rebuilding in the fashionable Gothick style. A couple of years after Byng didn’t visit Sir John ran out of money and had to go onto exile to escape debtors and the rebuild wasn’t finished for another 20 years.

There is a distinct sense of difference between the attitudes to these historic sites by Byng [and by inference his class] and those of the locals. Whereas he wants to explore they seem content [according to his comments at least] to accept and ignore. At Jervaulx, for example : ” I got an honest Yorkshire tyke to walk about with me, who knew nothing, but that ‘it was sadly blown up, and emaciated’. He spake also of the quality of materials taken away, and of several stone coffins being found, but was most intent to shew me where the jackdaws built, and was delighted at starting an owl”

This is by no means the full extent of this trip by Byng, so I’ll return to look at his comments on Fountains, Studley very soon

Long-standing readers of the blog may recall that I’ve written about two other tours by John Byng: one to Tintern and South Wales, and the other to Grimsthorpe and the East Midlands. All of his journals are available on-line now at Archive.org

You must be logged in to post a comment.