Last week’s post saw us follow John Byng’s trip from London to Yorkshire where he spent a lot of time peering at medieval ruins, exploring gardens and admiring picturesque landscapes.

In this week’s post he does all three in the same place: the estates of the Aislabie family: Studley Royal, Fountains Abbey and Hackfall.

Byng was clearly enthusiastic from the outset. He’d spent the day travelling to Ripon but “tho’ it was a gloomy threat’ning evening, yet, not to lose time I determined upon a survey of Studley Gardens, 3 miles distant.”

Was he impressed? or was it to be another verbal demolition job as we saw several times last week. At least it starts off well because “the Park is pleasant, with famous hawthorns, good trees, and fine views towards Ripon, and its old black Minster.” Will it continue in the same positive vein or will Studley Royal, Fountains and Hackfall disappoint? Have a guess and then read on to find out if you’ve judged Byng’s taste correctly.

As usual the photos are mine unless otherwise acknowledged

First of all though, who were the Aislabies who created the estate that Byng was going to visit? There isn’t time or space here to go into their story in any great detail, so suffice it to say that John Aislabie became MP for Ripon in 1695 and rose through government ranks becoming richer and richer on the way, until in 1718 he became Chancellor of the Exchequer. He was heavily involved with the South Sea Company and after it collapsed in the famous South Sea Bubble of 1720 he was accused of corruption, expelled from Parliament and disqualified from holding public office for life. That effectively forced him into exile on his Studley estate where he took up the pursuits of a country gentleman.

Luckily John Aislabie had long been interested in gardening, he was for example, a subscriber to John James’s Theory and Practice of Gardening (1712), and had already to begun laying out the water gardens at Studley in 1718. Now he continued on a grander scale until his death in 1742. The formal geometric design largely followed the French fashion of the period, but Aislabie adapted it to suit the Studley landscape, particularly in allowing for the ponds to be viewed from a series of terraces laid out on the hillside above. He also added a number of other garden features including a Doric Temple, a Gothic Tower, a cascade and fishing houses.

The gardens continued to be extended after Aislabie’s death by his son William, who perhaps surprisingly had been elected at the by-election to succeed his father as Ripon’s MP, holding the seat for the next 60 years. William added amongst other things, an Ionic Temple of Fame, and extended the gardens along the valley to the north of the water gardens creating an early example of a ‘picturesque’ landscape. With its rocky crags and woods, as well as a Chinese temple and garden it was a complete contrast to the geometry of the Moon Ponds designed by his father. As we’ll see this was just the start of his “improvements”.

Unfortunately Byng’s visit doesn’t really appear to get off to a good start because “the house seems to be of no particular account.” An earlier house had been rebuilt by John Aislabie in 1716, with a portico added later by William. After many alterations by later owners it burned down in 1946, and its remains were then demolished. The present house was created out of Aislabie’s magnificent stable block.

Byng then had a surprise – not because of the views but because “at the garden gate we left our horses; where, strange to tell, there is no cover built for them! (I suppose that Mr Aislabie rode, or possessed a good horse.)” This he clearly found shocking. However, as Mark Newman, the National Trust’s archaeologist for the area, points out, it implies that he didn’t explore the area around the house where such provision probably was made as there were a lot of visitors both by carriage and horseback and Studley had a rule that entry to the grounds was on foot. [The Wonder of the North, p.277]

Once inside though things begin to look up. “Nature has, here, been very bountiful in furnishing hill, vale and wood of fine growth, with a charming stream” but – and there’s always a but with Byng- as Studley was laid out in the first part of the century it was now outdated.

“Mr A. did not, I think, well consult the genius of the grounds, which are trick’d out with temples, statues, &c. and the water is carved with various shapes and no-where fully enlarged!”

The Gothic Belvedere or Octagon Tower

However, it was from one of Aislabie’s buildings, the “paltry Gothic temple with sash’d windows” that Byng reports “is first given, below you, a view of the noble remains of Fountains Abbey.”

The adjacent estate around the ruins of Fountains Abbey had been bought by William for £18,000 in 1767. He clearly had a fine sense of what he wanted. In contrast to the prevailing taste for overgrown ruins, he had parts of the structure consolidated and repaired, but other parts demolished. A lot of decorative carved stonework and tiles were retrieved during the clearing up process and then re-used in the restoration. He was not afraid of making additions too, with a gazebo built under the east window, to offer an elevated view of the nave. At the same time he stopped farming the surrounding land, taking down the field walls, canalising the river and planting lots of trees on the slopes opposite the ruins. He also opened the site to the public. So what Byng saw on his visit was a very carefully curated ruin laid out to very much to Aislabie’s idea of the medieval.

On the day of Byng’s visit the weather was wild and stormy but far from detracting from the pleasure it almost drove him into a state of ecstasy: “The rain now falling fast, drove us under trees, for shelter, whence we hasten’d to the Abbey… Oh! What a Beauty and perfection of ruin!! The steeple is complete; and every part in proper keeping,” Actually not every part was quite perfection because the Cloister Garden, one of the areas Aislabie had restored, was “infinitely too spruce; the ground of rubbish, of great depth, has been clear’d away, (as it should be done, but never is, in similar ruins) to the flooring, or that level.” However this meant he could indulge his antiquarian fancies because “here, from such trouble, has been discovered much Mosaic pavement of the Chapter House, with several inscriptions upon the Abbot’s grave stones.”

Proceeding from there he inspected “Where stood the Refectory, the Dormitory, the out offices, and the Abbot’s apartments ; but most of all to be admired the magnificent double Cloysters, whose roof has been admirably screw’d up” You sense his rising emotions as he notes that “In these I made a long walk of pious, melancholy reflexion. I crawl’d about here in the rain, till almost wetted thro’, regretting the bad, and ill-chosen time; and hoping that a further day might arrive, when I could dedicate the whole of it to this unique survey. The hollies and fir trees in these gardens are superb: indeed all the trees are very noble.”

Fountains Abbey & Bridge, by Francis Nicholson, 1794

image © Chris Beetles Ltd |

“There has been much wonderfully done by the late Mr A., [William Aislabie had died ten years earlier in 1781] but there is yet much to do; as proper planting around it — and for the small river, which runs beneath the Abbey, to be greatly enlarg’d.”

Byng was not alone at the abbey. While he rode over a party of tourists staying at his lodgings had hired a carriage to bring them over. He had conversed with them in passing but now watched in amusement as, to avoid the downpour ” the chaise company skulk’d under arches.” Meanwhile he ” was two hours in my survey; a miserable time for the poor horses; but luckily the saddles were not wetted. I trotted back, the way we shou’d have come, and instantly sought for dry stockings, and for brandy, to make an ablution. I also heated myself with coffee and toast.”

The next morning “The chaise tourists now took their departure in two chaises: hence they go to view (the late) Mr Weddel’s seat at Newby; and they civilly offer’d me a seat in their chaises; but I do not envy chaise tourists, who are to be hurried, and jolted along, in danger of bad roads, and without ever seeing a County to advantage; and why go away in such a rainy morning, when everything must appear to disadvantage?” Instead he wandered round Ripon seeing the Minster and other sights until the weather cheered up then at 3.00 set off for Hackfall.

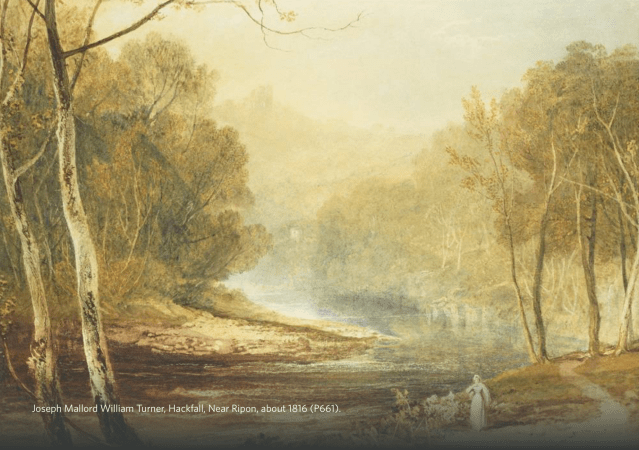

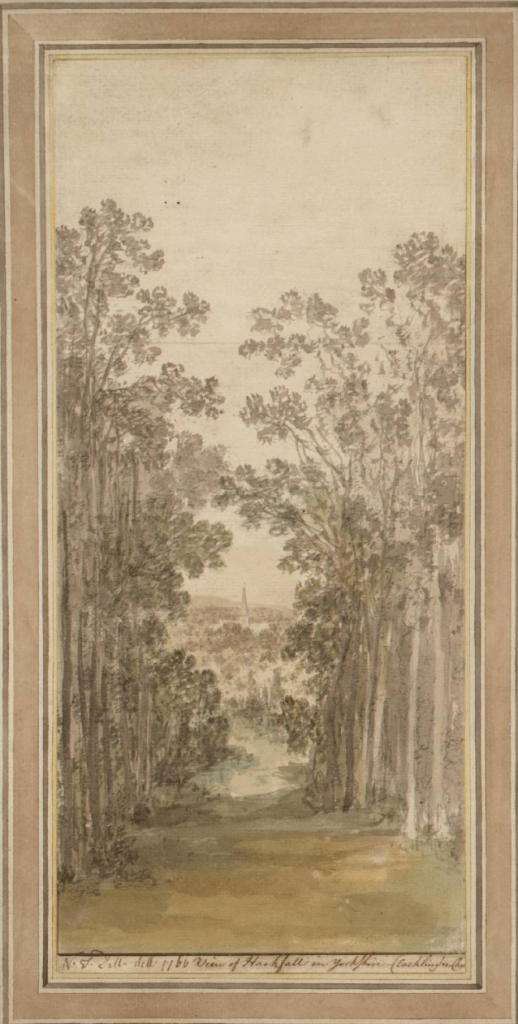

John Aislabie bought Hackfall Wood, some xx miles from Studley and Fountains for £906 in 1731. It’s unlikely he had any other object in mind other than felling its timber, or exploiting its lime, coal and sandstone. However William saw its aesthetic potential and began transforming the valley into the antithesis of Studley: a ‘natural’ Gothic landscape with follies, waterfalls, views and glades with several unusual built structures. These included the Banqueting House, probably designed by Robert Adam, Mowbray Castle, Fisher’s Hall and a Grotto.

The site is an important and early example of one which exploited wild natural scenery for its own sake, and several scenes even featured on the Green Frog dinner service, which was commissioned by Catherine the Great from Josiah Wedgwood [see this earlier post for more on that]

The Weeping Rock: A Waterfall at Hackfall Near Ripon, by Anthony Devis c1770

Harris Museum & Art Gallery

Byng, to his surprise [and indeed mine] had little idea what to expect since he noted it was”strange, that no account, nor prints of this place, have been published; at least I never saw any! “He found “the road stoney and disagreeable thro’ an enclosed country of no particular observation to the village of Grewelthorp, at the end of which we dismounted at the house of the gardener, who has the superintendence, and shewing of Hackfall Woods, and Walks.”

“Here, thinking myself weatherwise, I held a council with G, [his manservant] and the gardener. ‘The weather is coming up wet, (spake the foreman). Had I not better pass on, and return tomorrow.?’ No, answer’d the gardener, (fearful, perhaps of my never-return) the weather will be fine’. So we put up our horses; (for here are places for horses; tho’ to the shame of Studley, all horses there must stand exposed !).”

Once again we see Byng wax enthusiastic : “There is so much to admire, so much to celebrate, that I know not how to proceed in description, or speak half in praise due to Hackfall. …Entering the wood by a small gate, the path, which, tho’ wild, is sufficiently well-kept, passes by a rattling rivulet, forming many natural cascades : and from the hill tops the rills are so collected, as to flow in narrow silver currents thro’ the wood.”

Of course it was not perfect because “here, as well as at Studley, the walks should be widen’d, and small carriages admitted. At Studley, art is not too predominant; here Nature is consulted, and in abundant beauty she revels.

By this time he had realised, as many of us, when turning up mid-afternoon to see an unknown garden that we haven’t given ourselves enough time. Byng comments that in fact “A day, (if an Italian [ie sunny] day), should be devoted to this inspection. Wine and provisions might be brought in a cart; and then music, and love, to fill the scene, Hackfall would appear an Eden. If mine, I should build in, or enclose it; for I could not be distant from such a mistress. There are many rural buildings, and seats; and a castle, call’d Mowbray’s Castle, has been erected upon a woody summit, and without offence to the character, and scenery of the place.”

For more on Mowbray Castle see this informative post by The Folly Flaneuse

He went on to describe how “overhung by steep, wooded hills, the rapid and romantic River Eure frames its broad and rapid course, (nobly swell’d by the late rains) wherein the angler will find abundant pastime from the numbers of salmon and trout : nothing can be more grandly wild, and pastoral, than the unexpected view of this river! From the hill tops, at various spots, are transcendent views, even as far as York Minster. Let those who possess steep; wooded hills, of spungy summits with streams beneath, learn from Hackfall how easy and cheap it is to form enchanting walks, and to guide the ripple down the hill. At one point — several of these rills are to be seen, gliding thro’ the wood like streaks of liquid silver.”

Hackfall, being in shade, and softeness, requires hot summer days for its visitations ; unluckily my evening (an evening inspection is wrong) was in gloom, and it felt damp, and cold. — Two hours did I employ in my walk, (4 mile I should reckon it;) and when I approach’d the last ^ mile, the rain began to rattle upon the leaves! ‘Now, gardener, we must hurry’! I should have deferr’d my visit till the morning…

We re-enter’d the gardener’s house, a nice cottage it is, and therein sheltering myself in a snug parlour (for the rain fell in buckets) I discours’d with the gardener about these 2 gardens; about old Mr Aislabie, his taste, and works; of the gardener’s own age, and family…Thus the time jogged on, till a long stay, or to escape wetting were impossible

but I hope, charming Hackfall, to see thee once again’.

Aislabie’s descendants sold Hackfall to a timber merchant in 1933 who felled large numbers of mature trees causing major damage to Hackfall’s ecology and severely damaging some of the buildings and paths. It was acquired in 1989 by the Woodlands Trust, and registered at Grade 1 on the English Heritage “Register of Parks and Gardens of Historic Interest”. Meanwhile Studley Royal and Fountains remained in the family until 1966 when they were bought by West Riding county council. The National Trust took over ownership in 1983, gaining world heritage for the site in 1987 and attracting 425,000 visitors in 2023/24, putting it near the top of the most visited properties, although they weren’t allowed to crawl all over the ruins like Byng. I wonder what he’d have thought?

Aislabie’s descendants sold Hackfall to a timber merchant in 1933 who felled large numbers of mature trees causing major damage to Hackfall’s ecology and severely damaging some of the buildings and paths. It was acquired in 1989 by the Woodlands Trust, and registered at Grade 1 on the English Heritage “Register of Parks and Gardens of Historic Interest”. Meanwhile Studley Royal and Fountains remained in the family until 1966 when they were bought by West Riding county council. The National Trust took over ownership in 1983, gaining world heritage for the site in 1987 and attracting 425,000 visitors in 2023/24, putting it near the top of the most visited properties, although they weren’t allowed to crawl all over the ruins like Byng. I wonder what he’d have thought?

You must be logged in to post a comment.