A couple of weeks ago I led a small party of French visitors round some of the gardens of London, Kent and Sussex. One of those I chose was Hever Castle which I hadn’t visited since lockdown. We were all so impressed with what we saw that I’ve decided to update my much earlier post about it.

A couple of weeks ago I led a small party of French visitors round some of the gardens of London, Kent and Sussex. One of those I chose was Hever Castle which I hadn’t visited since lockdown. We were all so impressed with what we saw that I’ve decided to update my much earlier post about it.

The castle looks as if it should be in a children’s storybook. Although it’s small it’s perfectly formed with battlements, a moat with a drawbridge and a flag. In front, lining the approach path is a collection of topiary and behind it what appears to be a half-timbered Tudor village. All lovely but nothing compared with the hidden delights of the gardens which are mostly tucked away out of immediate sight.

The photos are mine unless otherwise acknowledged. Most are recent but a few date from an earlier visit one spring – hence the tulips!

The photos are mine unless otherwise acknowledged. Most are recent but a few date from an earlier visit one spring – hence the tulips!

The castle itself dates back to 1270 and passed in 1462 into the hands of Sir Geoffrey Bullen who had been Lord Mayor of London and was presumably trying to move into the gentry by buying a country estate, or in his case a second one since he already owned Blickling in Norfolk.

In 1505 it was inherited by his grandson Sir Thomas Boleyn – note the more upmarket version of the family name – and by then it had become a more comfortable Tudor manor house. Sir Thomas, later Earl of Wiltshire, was one of Henry VIII’s leading diplomats, before the king married his daughter Anne.

Anne Boleyn

anon, late 16th copy, of a work of circa 1533-1536. NPG

The execution of Anne, and her brother led to the earl’s fall from grace and soon after his death in 1539 Hever passed into royal hands and was then given to Henry VIII’s fourth wife, Anne of Cleves, along with many other manors and estates, as part of her divorce settlement. From then on Hever slowly declined in importance and the castle became little more than a modest farmhouse for a succession of tenant farmers, until its fortunes changed in 1903. And WOW did they change and change fast.

The cause of this good fortune was William Waldorf Astor, a member of the very wealthy Astor family of New York. After a not particularly successful career in politics in 1882 he was appointed ambassador to Italy where he discovered a love of art, and in particular classical sculpture. After his father died in 1890 he inherited a vast personal fortune that made him the richest man in America, but growing increasingly disenchanted with the US which was ‘no longer a fit place for a gentleman to live’ he upped sticks and moved to England the following year.

He was to become a British citizen in 1899. By 1893 he had bought Cliveden , and two years later he commissioned the famous Victorian church architect John Loughborough Pearson to design an amazing mansion on the Embankment. Now known as Two Temple Place it was to serve as a business HQ and town house. Although Astor took up many business interests including The Observer newspaper he was clearly looking for another big project. He found this at Hever.

Astor first saw the castle in July 1901 and fell in love with it immediately. Two years later he’d bought it along with the estate of 630 acres. Astor clearly liked developing good working relations with his contractors and, so when he decided the castle wasn’t big enough for his social life, and needed work doing, he chose the same team who had worked on Temple Place. Frank Loughborough Pearson, son of John [who died in 1897] was asked to modernise and restore the castle and create additional guest accommodation, while the work was carried out by the old established firm Thompson’s of Peterborough and Battersea who had built Temple Place.

They were experts in church repairs, and had a reputation for stonemasonry and ornamental ironwork as well as a royal warrant for work at Sandringham. Work began on the restoration of the castle in September 1903 with Thompson’s employing as many as 748 workmen on the project.

Things were done in the best Arts and Crafts tradition: every fragment of the original structure that could be preserved was, whilst later “improvements” were removed or replaced with the best quality alternatives available. Wherever possible work was done in the traditional way using tools such as the adze. As I said no expense spared.

Its difficult to know who came up with the initial idea but Pearson oversaw the creation of the faux Tudor Village, which consists of a series of one- and two-storey cottages of brick and stone, with half-timbered upper floors, and totalling 100 rooms. It was linked to the Castle by a covered bridge. At the same time Astor insisted on the latest comforts such as central heating, a fire-protection system and an independent power supply.

Creating the village was not a straightforward job as the existing outer moat which can be seen on the OS map for the 1890s had to be filled and the river Eden pushed back nearly 100m from its course.

An artificial river bank had to be created with a strong retaining wall, based on rocks quarried on site. It didn’t quite go according to plan as during the first winter floods still managed to get into the foundations so a tiled cellar was built under the building.

Astor was also determined to find or create a home for his ever-growing collection of classical statuary and in this he was fortunate – or shrewd enough – to find Cheals of Crawley, a firm of Sussex nurserymen and increasingly garden and landscape designers to work alongside Thompsons.

Over the course of four years between 1903 and 1907 between them they created what David Ottewill describes in his book on Edwardian Gardens as “the most spectacular Edwardian classical garden in England, epitomising both the romantic nostalgia and the opulence of the age.”

It’s hard to fully grasp the extent of what Astor took on and what he achieved. When he acquired Hever there was virtually no trace of any garden with the exception of a few old fruit trees, but in the four years between 1904 and 1908 its estimated that about 1000 men worked on the site transforming it from a series of damp waterlogged fields into the 125 acres of formal gardens and more informal “natural” landscapes seen today.

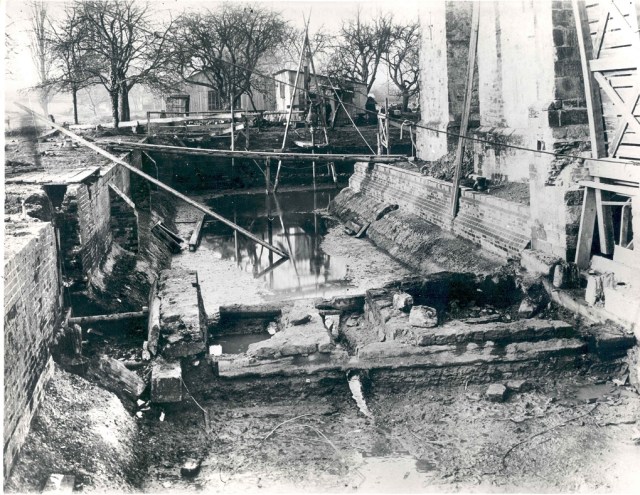

Astor showed the truth of the old adage that in gardening preparation being everything. Contractors were brought in to lower ground levels around the castle, and to dig a new outer moat, widen the river Eden and then excavate a 38 acre lake with lock gates which control the level of the water upstream from the castle. The inner moat which was once joined to the river Eden with whose levels it rose and fell often flooding the courtyard, had to be made watertight. Millions of tons of soil were removed and carried away by a small railway system, steam diggers assisted but most of the initial work and loading of trucks was done by hand. The preparation, costly and time-consuming though it was, paid off.

Nowadays as the visitor descends the hill from the entrance the castle and Tudor Village come into view in the best tradition of the picturesque, at times hidden behind shrubberies and trees and at others in full view. It is an impressive approach and, even with the intrusion of modern tourist paraphernalia such as a cafe, signage and tarmac paths it’s easy to see why Astor was captivated.

The castle seen behind what is called Anne Boleyn’s orchard

On the western [left] side of the castle and in front of the guest village is a beautiful meadow/orchard, – known surprise surprise as Anne Boleyn’s Orchard – which contains mainly old varieties of apples and pears. Its position echoes the one shown on the Ordnance Survey map of the 1890s.

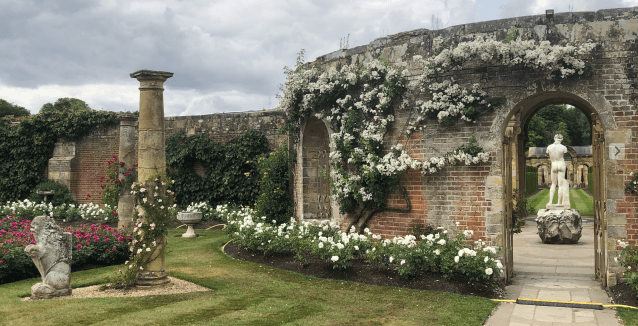

On the other side of the castle a much more formal new outer moat, parallel with the original moat, was dug out, and between the two moats Cheals laid out a series of small intimate spaces including “many interesting features appertaining to the Tudor period” which together form the – yes you’ve guessed it – Anne Boleyn Garden.

There is a rose garden, a fountain garden, yew alleys, a maze, and more topiary work, notably a set of chessmen “clipped out of yew to the Tudor pattern.” The garden was not in any sense a “recreation” of a 16thc garden but rather a romantic re-imagining.

Money was clearly no object and Cheals imported 1000 6 foot high yew trees from Holland to create the maze, while the chess pieces and other topiary were grown on metal frameworks in their own nursery grounds for 3 years before they were bought to Hever and planted out in 1906-7.

Going east from the castle the path leads alongside the lawn to an impressive stone basin- the Half Moon Pond, with water jets and statues of Venus and Cupid.

Backed by tall yew hedges it forms a backstop to the sweep of lawn with, on either side, the entrances to Hever’s grand Italian Garden which was designed by Pearson, built by Thompsons and planted by Cheals between 1904 and 1907.

The grand Golden Gates have recently been restored at a cost of £35,000.

The Half Moon pond under construction

The Italian Garden can also be reached by a new path that runs along the outside of the high surrounding wall, next to a narrow extension of the lake, making what’s on the other side even more of a surprise.

This area has been planted in what might loosely be called a contemporary style which works really well with the marble urns dotted along the walk.

Gated entrances along the wall lead into roofless circular pavilions which offer breathtaking views through an arcaded screen into the gardens beyond.

The first impression is of the sheer scale of the site, and the second, almost instant realisation is that you’re only seeing a fraction of it. In its entirety the Italian garden is 220m long and 80m wide. The walls are sandstone and about 4m high with broad paved walks in front of them.

Although the gardens are formal and in proportion they are not perfectly symmetrical and indeed the two long sides are very different. On the northern side of the garden is the Pompeiian Wall, which is divided by buttresses into a series of bays which are home to a large part of Astor’s classical sculpture collection imported from Italy. The arrangement wasn’t to everyone’s taste and Ottewill says it was “only redeemed by the planting of shrubs and climbers by Cheals, which created a dream-like vista of marble gods and goddesses festooned with clematis, magnolia and other delectable flowers and foliage.”

I have to disagree. It’s the whole ensemble that makes it work so well. The permanent planting is indeed excellent, and backed up by temporary planting of spring bulbs – particularly tulips – and bedding, all testament to the skill of Hever’s garden team, but without the antiquities it would lack surprise and focus.

At the far eastern end of the gardens is a monumental loggia running the full width through which the visitor catches a view down the length of the lake. Through the colonnade elaborate balustrade steps lead down from the loggia to a paved area overlooking the water.

The centrepiece is the marble Nymph’s Fountain with its female figures and cherubs carved by William Silver Frith. It was inspired by the Trevi Fountain in Rome and installed in 1908. Much of the area adjacent to the lake itself has recently been restored.

Running along the whole length of the other, southern, side of the garden is a stone and timber pergola, covered with vines, wisteria, and other climbers.

It passes through several different garden areas including a large rose garden most of which open over narrow borders to the central lawn.

It also passes the Guthrie Pavilion built as a cafe and events space, then offices and a service area before reaching the slope of the hill but on the way Thompsons and Cheals achieved a minor miracle.

The western end of this pergola shades a series of shallow bays against the slope which house camellias before reaching a long shallow gallery of shaded rock-work.

Here the retaining wall built into the hillside was faced with rock from a local quarry at Penshurst. Hidden pipework allows water to spurt or trickle over moss-covered outcrops or gargoyles into a narrow pool along at the base. Moisture-loving plants grow everywhere and anywhere they can. Because the gargoyles are constantly wet and open to the elements they have begun to require replacing and, rather like mediaeval cathedrals, new heads have been made in likenesses of people connected with the site including the head gardener.

Constructed and planted by Cheals between 1904 and 1906 this rockwork feature was not an accidental choice. In February 1903 Joseph Cheal was sent by Astor to Italy to visit gardens and bring back ideas for Hever. One of the many places he visited was the Villa d’Este at Tivoli where he was inspired by the gallery of 100 fountains. On his return Cheal lectured about his trip and wrote an account of the history of Italian gardens which was published in the RHS journal in 1908.

Constructed and planted by Cheals between 1904 and 1906 this rockwork feature was not an accidental choice. In February 1903 Joseph Cheal was sent by Astor to Italy to visit gardens and bring back ideas for Hever. One of the many places he visited was the Villa d’Este at Tivoli where he was inspired by the gallery of 100 fountains. On his return Cheal lectured about his trip and wrote an account of the history of Italian gardens which was published in the RHS journal in 1908.

Aerial view from the Hever Castle Facebook page

The central areas of the garden are largely laid to 2 lawns totalling something like 4 acres in extent with borders and some large pieces of architectural sculpture…

but between them is a sheltered yew-hedged sunken garden with its own micro-climate.

This is laid out with a central lily pool surrounded by lawn and semicircular oak seats in walled niches. The garden was originally designed by Cheal to contain a Roman bath with a marble surround which was replaced by the present pool in the 1930s.

Copy of an estate map dated 1756

As can be surmised from the estate plan above the 38 acre lake beyond the Italian garden is man-made. It was created by Astor from the meadows that lay to the east of the castle and involved diverting the river Eden. Work began in 1904 and the contractors employed about 800 men to “carry on the works regularly and continuously by day and night (except on Sundays) when so ordered”. It took two years to complete and was filled in the summer of 1906.

Millions of tons of soil were removed and carried away by a small railway system installed especially, although all the initial work and loading of trucks was done by hand. A 16 acre island was also created and on it Cheals planted a half-mile long double avenue of chestnuts in line with Astor’s library window. As with the other trees planted around the grounds many did not come from Cheals own, or indeed any other nursery, but were dug up in the surrounding estate and wider countryside including the Ashdown Forest. For an idea of how this transplantation worked see this previous post.

Sixteen Acre island also now boasts a very popular water maze installed in the late 1990s around a small central rock tower which offers views out over the surrounding landscape, as well as the opportunity to get thoroughly soaked in the process.

Walks have been laid out around the lake, with a lot of additional planting and seating being added, including areas of colourful ornamental wild flowers and other annuals such as cosmos which should look spectacular later this year.

Completing the lake circuit leads back either to the lawns in front of the castle or past another events venue…

…behind which a path leads up through an avenue of shrub roses up to the wooded ridge that overlooks the castle. Planted originally with rhododendrons and other shrubs which had become overgrown the area is now being carefully renovated and improved.

One path known as the Sunday Walk leads up a steep-sided valley through well-established trees and shrubs to the village church where Thomas Boleyn is buried. This area has been radically transformed over the last few years, and is a really impressive piece of both design and planting, with yet more reclamation and improvement in process.

One path known as the Sunday Walk leads up a steep-sided valley through well-established trees and shrubs to the village church where Thomas Boleyn is buried. This area has been radically transformed over the last few years, and is a really impressive piece of both design and planting, with yet more reclamation and improvement in process.

I spoke to one of the gardeners who was busy planting out a new area and discovered that work had been going for the last six years, with several more years work envisaged before the scheme would be complete, and then of course it would be time for revision!

I spoke to one of the gardeners who was busy planting out a new area and discovered that work had been going for the last six years, with several more years work envisaged before the scheme would be complete, and then of course it would be time for revision!

There are also gardens laid out at a small former quarry. All this was planned and planted by Cheals.

For the 4 years they were working at Hever Cheals employed between 80 and 100 local workers who mostly cycled in from surrounding villages and who were paid an average of £1 a week. It was the firm’s biggest ever contract and their masterpiece, confirming their reputation as great landscapers.

For the 4 years they were working at Hever Cheals employed between 80 and 100 local workers who mostly cycled in from surrounding villages and who were paid an average of £1 a week. It was the firm’s biggest ever contract and their masterpiece, confirming their reputation as great landscapers.

Work on the Hever estate reputedly cost Viscount Astor as he was to become in 1917, about £10 million (thought to equate to about £1 billion today) with about 10% of that going to work in the garden. The Astor family sold Hever in 1983 to Broadland Properties who are clearly committed to its long term sustainable future.

The mock Tudor village is now a luxury hotel, spa, and wedding venue but the gardens have become a visitor attraction in their own right with Broadlands clearly caring for them and respecting their historic value. They are maintained by a team of 11 paid gardeners and, as always these days, a group of volunteers. I’m sure that Astor would be proud of their achievements in conserving and continuing to improve what has to be one of the most magnificent gardens in Britain.

You must be logged in to post a comment.