“Pushing through the scrub, beautiful sprays of orchids forced themselves on your attention by brushing your face. The next few steps would have to be tunnelled through climbing fern, and then more orchids on trees with moisture continuously dripping off fringes of moss. Large clusters of a leguminous bloom like white acacia drooped from small trees. There were cream, pale lemon, and brilliant blue orchids, but the colours orange and scarlet predominated, flaming out of the green”

Who do you think wrote that ?

When I first read it I wondered if was an extract from the journal of an intrepid but rather romantic Victorian plant hunter. In fact it’s an extract from an admittedly Victorian-explorer-sounding book called Six-legged Snakes in New Guinea, and as you’ve probably gathered from the title of the post the author wasn’t quite the bearded pith-helmet wearing explorer that I’d imagined but instead was an extraordinary woman: Evelyn Cheesman.

When I first read it I wondered if was an extract from the journal of an intrepid but rather romantic Victorian plant hunter. In fact it’s an extract from an admittedly Victorian-explorer-sounding book called Six-legged Snakes in New Guinea, and as you’ve probably gathered from the title of the post the author wasn’t quite the bearded pith-helmet wearing explorer that I’d imagined but instead was an extraordinary woman: Evelyn Cheesman.

Cheesman wasn’t primarily a plant hunter but that was an adjunct to her principal passion: entomolgy. Both interests led her to travel all over the world, notably the South Pacific where she went on eight one-woman expeditions, and in 1938 discovered a new blue orchid.

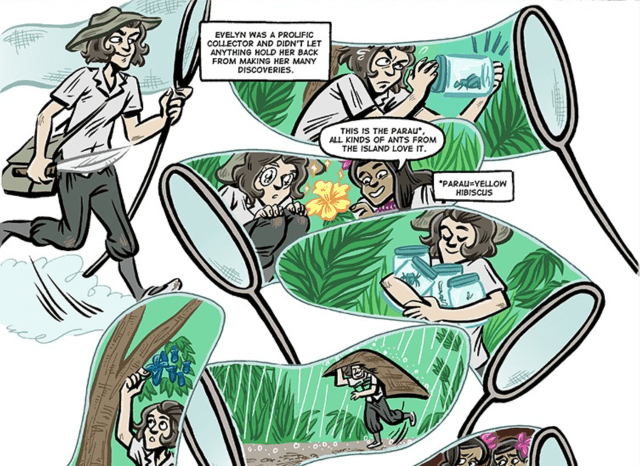

The Natural History Museum commissioned a cartoon strip history of her life from Sammy Borras, and I’ve taken the liberty of choosing a few frames to help illustrate this post, but I’d highly recommend checking out the rest of the story at the museum’s website

Cheesman was very self-deprecating, saying in her own account of some of her adventures “the person herself is not interesting” but as her publishers added in the preface, that was “an opinion we cannot share”. [Things Worthwhile 1957] . I have to agree. After all someone “not interesting” is unlikely to have written books with titles including Camping Adventures in New Guinea and Camping Adventures on Cannibal Islands.

Cheesman was very self-deprecating, saying in her own account of some of her adventures “the person herself is not interesting” but as her publishers added in the preface, that was “an opinion we cannot share”. [Things Worthwhile 1957] . I have to agree. After all someone “not interesting” is unlikely to have written books with titles including Camping Adventures in New Guinea and Camping Adventures on Cannibal Islands.

I’ve had to resist the temptation not to talk about incidents such as her being caught in a giant spider’s web, accidently sending a poisoned spear to King George V, or her reactions to discovering leeches in her teapot. But so you can discover more for yourselves it’s worth looking at the long list of her books on her Wikipedia entry although sadly, only a few of which are available digitally. Instead I’m going to try and stick to the story of the blue orchid.

Orchids have cropped up on this blog several times over the years – the annual orchid festival at Kew, James Bateman’s great Orchid book; how orchids got their name; ; the Victorian orchid nurserymen Benjamin Williams; and William Bull; Charlotte Cuffe and orchids in Burma; but I’d only ever heard of one blue orchid – Vanda caerulea – and even that is really more purple than blue. Indeed although orchids come in virtually in every colour of the rainbow, true blue ones, especially those which grow as epiphytes on trees, are extremely rare, with just a tiny handful – mainly Australian terrestrial species – known among the 26,000 wild orchids which have so far been described scientifically.

However, in 2013, and to much excitement, Kew’s leading orchid scientist, Dr André Schuiteman, announced the discovery of a new one. It came from Waigeo, the largest of the 1,500 islands and islets that make up the remote and biologically rich Raja Ampat archipelago off the north west coast of New Guinea. Due to its geological isolation, the island is a hotbed of evolution that has given rise to the kind of species richness described by Charles Darwin as ‘endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful’, and which Darwin’s contemporary and friendly “rival” Alfred Wallace made the first serious attempt to explore and catalogue in 1860. [See Wallace’s account in The Malay Archipelago, 1867]

But, and its a very big BUT Dr Schuiteman did not find the blue orchid on Waigeo, but in the herbarium of London’s Natural History Museum. Sorting through unidentified Dendrobium orchid species from New Guinea, he noticed two herbarium sheets on which were mounted what he described as “some unremarkable -looking specimens” whose typed label read “‘orchid growing on trees; flowers deep sky blue”. They weren’t named or classified in any other way however, although the colour had faded, he noticed the flowers had a strange bluish-grey tint, rather than one of the many shades of brown usually seen in old dried orchid specimens. Was it possible that this was an as yet un-described species that really had been sky blue?

What you can’t really tell from the image is that the plant is very small, with only one or two flowers – perhaps an inch [2.5cm] long on a stem. Despite its brilliant colour it must have been quite difficult to spot. The labels also revealed that the specimens had been collected by one L.E. Cheesman on 17 June 1938 on the summit of Mount Nok, an extinct volcano on Waigeo. Dr Schuiteman now set out to discover more about L.E.Cheesman, as did I when I first came across the story of the “new” blue orchid.

Born in 1881, appropriately the same year the Natural History Museum opened, Evelyn Cheesman was always interested in natural history and dreamed of becomng a vet. In 1906 she was refused permission to study at the Royal Veterinary College because women were not accepted as students, so instead she travelled to both France and Germany to learn languages which skills she was later to use to advantage at the Admiralty during World War I. However in 1917 she met Harold Maxwell Lefroy, professor of entomology at Imperial College and honorary curator of the insect house at London Zoo. After studying with him, she was persuaded in 1920 to accept the position of curator of insects at the zoo: the first woman to be employed as a curator there.

Exotic specimens were hard to find so instead she worked with a group of young volunteers and organised displays of insects they had collected around London. Her exhibits of British butterflies, her British caterpillar nursery, ant colonies, and the occasional exotic stowaway supplied by Covent Garden fruiterers, proved so satisfying that when, a few months into the job, the Veterinary College announced its intention to admit women, she was no longer interested.

She also began broadcasting news about her ant colonies on the recently instituted BBC radio programme Children’s Hour.

It was in 1924 that her travelling began. She took the post of entomologist with an expedition that was to explore the West Indies, Panama, the Galápagos Islands, and then the south Pacific. It proved to be the first and last group trip she would undertake because she disliked the restrictions imposed by group travel so much that not long after arriving in the Galápagos she left the group so she could explore and collect at her own pace. All her future expeditions were solo.

In 1926 she left the zoo and attached herself, unpaid, to the Natural History Museum, learning taxonomy in the hope this might lead to further travel opportunities, and supporting herself by writing popular science and, later, accounts of her adventures and discoveries. Her scheme worked and in 1930 she embarked for the New Hebrides [now Vanuatu] on the first of her single-handed collecting expeditions across the Pacific. Her budget for the year-long trip was £300 including the return fare via Australia, the wages of the locals she hired to carry her equipment and specimens, and all her food. Next up was a trip to New Guinea in 1933, the island that was to become her favourite.

It was her work in New Guinea and the southern islands of Vanuatu that led her to suggest that their flora and fauna was Asian in origin, not Australian as generally accepted. There’s more on this see the section on biogeography in The Person Herself Is Not Interesting”

Her photo of Mount Nok from Six Legged Snakes

During her lifetime Evelyn Cheesman collected some 70,000 natural history specimens of all kinds, mainly insects, but also many plants and flowers. Amongst them was the bright blue dendrobium which she found growing on trees in cloud forest at an altitude of about 2,500 feet near the summit of Mount Nok. It’s worth saying at this point that this new orchid isn’t a huge showy affair – its flowers are only an inch [2.5cm] long and only one or two are borne at a time. She brought it back to London as a dried pressed specimen and gave it to the museum, where it remained in obscurity for more than 70 years.

I wonder if she bought back specimens of another orchid that she found, related in this clip from Six Legged Snakes when she was camping on Mount Nok.

After further research on the specimen Dr Schuiteman published a proper scientific account of the plant naming it Dendrobium azureum, and unsurprisingly wanted to know if it could still be found in the wild. This was not as straightforward a question as it might sound because deforestation in Indonesia was [and still is] rampant, on a par with if not worse than in the Brazilian Amazon. Given that Dendrobium azureum has not been reported from any other location it was thought quite likely to be endemic to Waigeo, where large-scale logging was already a well established threat. The answer had to be an expedition to see if it could be found before the loggers chainsaws reached it. Dr Schuiteman had already been on several expeditions to the tropics in search of orchids and other plants, including four to New Guinea and now hoped for another.

Meanwhile a team of local conservationists from West Papua’s Natural Resources Conservation Centre and staff from the Indonesia team of Fauna & Flora were conducting a routine biological survey in the forests of Waigeo. To everyone’s amazement while searching for a rare bird in the stunted mossy forests on the windswept and foggy slopes of Mount Danai they stumbled across the blue orchid – the first time that Dendrobium azureum had been documented in the wild. Since nothing was known about the population, distribution or life cycle of this orchid the team undertook follow-up surveys, and did indeed discover more, although it’s thought that are less than 100 plants of the blue orchid.

But that wasn’t all. Along with about 80 other rare plant species, several of which are thought to be endemic to Waigeo including unique forms of rhododendron, myrtle, soapberry and pitcher plant, they also found a second new-to-science orchid species : the bright red. Dendrobium lancilabium, subspecies wuryae,. This was named in honor of Hj. Wury Estu Handayani Ma’ruf Amin for her contributions to the conservation of orchids and other local flora in West Papua province.

The findings of the local team were written up in Malesian Orchid Journal. Unfortunately the article is only available to purchase, and at a price I couldn’t justify. However there’s an abstract on Researchgate

The findings of the local team were written up in Malesian Orchid Journal. Unfortunately the article is only available to purchase, and at a price I couldn’t justify. However there’s an abstract on Researchgate

Unfortunately too, Dr Schuiteman still hasn’t been to Waigeo. Such an expedition is not only expensive to mount, but it’s also difficult to get all the necessary permissions, as most of the island is a protected area. He is still hopeful to get there one day and see the blue orchid for himself.

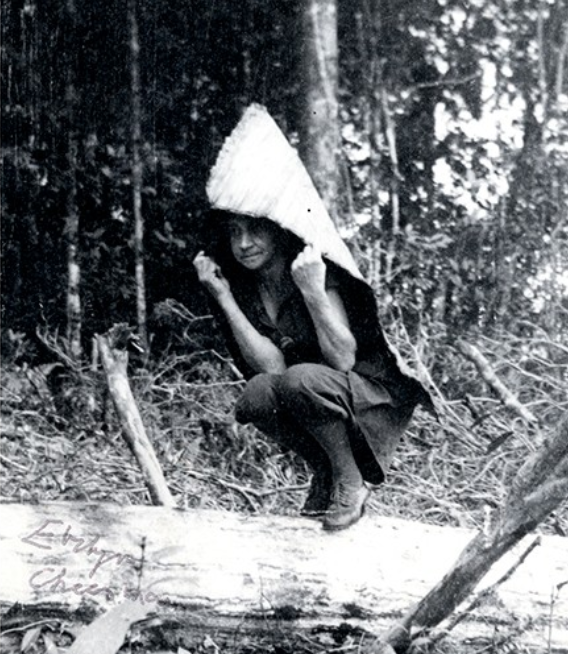

As for Evelyn Cheesman, she carried on exploring the fauna and flora of the southern Pacific islands with her last trip being in 1954 when she was 73. Photographs in her later years show her as a frail old woman leaning on a stick, but dressed in her working gear of floppy, many-pocketed tunic, bloomers, canvas shoes, and wide-brimmed hat.

As for Evelyn Cheesman, she carried on exploring the fauna and flora of the southern Pacific islands with her last trip being in 1954 when she was 73. Photographs in her later years show her as a frail old woman leaning on a stick, but dressed in her working gear of floppy, many-pocketed tunic, bloomers, canvas shoes, and wide-brimmed hat.

She clearly had a good rapport with the indigenous populations, respecting their cultures, and learning much from them, especially survival skills, and writing with sensitivity about an ecology and forms of tribal life that were disappearing even in her time.

The house the villagers built for her on Waigeo, complete with a ten foot ladder to climb to the door. from Six legged Snakes

She was rewarded by local people with the honorific title ‘the woman who walks’ because she flatly rejected the cumbersome sedan chairs used by most European women who visited the island. Others called her ‘the lady of the mountains’, a name she was very proud of saying that “the Victorian lady deep inside her particularly liked” it. (from Things Worth While).

She was rewarded by local people with the honorific title ‘the woman who walks’ because she flatly rejected the cumbersome sedan chairs used by most European women who visited the island. Others called her ‘the lady of the mountains’, a name she was very proud of saying that “the Victorian lady deep inside her particularly liked” it. (from Things Worth While).

Back in Britain she tried to make sure through her books and broadcasts that no one need be excluded from sharing in the discoveries she had made and the sights she had seen. During the production of one of her radio programmes in 1956 she encountered both a young Gerald Durrell as well as David Attenborough, who remembered being rather in awe of her.

In 1948, the museum’s board of trustees made Evelyn an honorary associate, and her contribution to science was further recognized in 1955 with an OBE. A sign of her humour can be seen following an accident when she was knocked down by a car in 1962 and she commented that “it was a window cleaner’s van overtaking. . . . I do think the fates might have sent at least an archbishop in a Rolls Royce.” She continued to work and help younger scholars until her death on 15 April 1969.

In 1948, the museum’s board of trustees made Evelyn an honorary associate, and her contribution to science was further recognized in 1955 with an OBE. A sign of her humour can be seen following an accident when she was knocked down by a car in 1962 and she commented that “it was a window cleaner’s van overtaking. . . . I do think the fates might have sent at least an archbishop in a Rolls Royce.” She continued to work and help younger scholars until her death on 15 April 1969.

In summary Evelyn Cheesman was a model for explorers of either sex, urging those who dared to set off for the unknown. As a scientist, she was remarkable, and as a woman unwilling to accept age- or gender-based limitations, she is inspirational. It’s great to know that the rediscovery of the blue orchid has bought her back to wider public notice.

You must be logged in to post a comment.