Let’s begin with a conundrum: what’s special about Gunnersbury Park? More specifically, why does it boast not one but two large houses, both built around 1800-1802 which stand side by side almost within touching distance of each other?

Nowadays Gunnersbury is a popular large public park stretching to 186 acres, hemmed in by the M4, the North Circular road and dense suburban housing, but for most of its nearly 700 years of documented existence it was home to a succession of wealthy families – and even to a princess. All but one of them lavished money and attention on the site, leaving their mark on its gardens and buildings. The exception was a property speculator, John Morley, who planned to redevelop the site, for housing, luckily largely unsuccessfully.

But that doesn’t provide an obvious answer to the question of why the two houses? So read on to find out more about Gunnersbury and its not-quite-twin mansions

as usual the photos are mine unless otherwise acknowledged

Gunnersbury gets its first mention in documentary records as early as 1347, but after a short period when it was in the hands of Edward III’s mistress it passed to the Frowyck family who were prominent citizens of the City of London – merchants, judges, lawyers and even MPs and lord Mayors – until the late 16th century. The site of their manor house is thought to have disappeared underneath the North Circular road which now runs down the edge of the park.

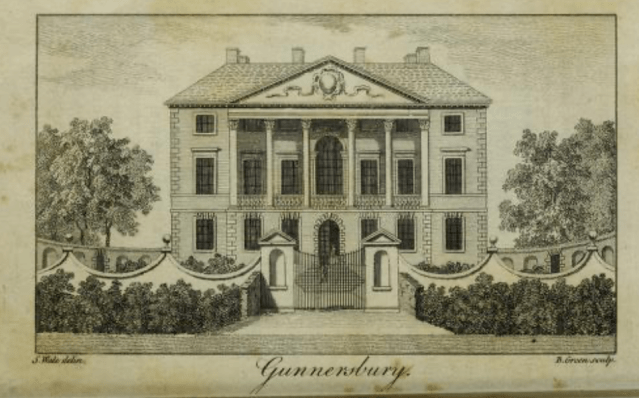

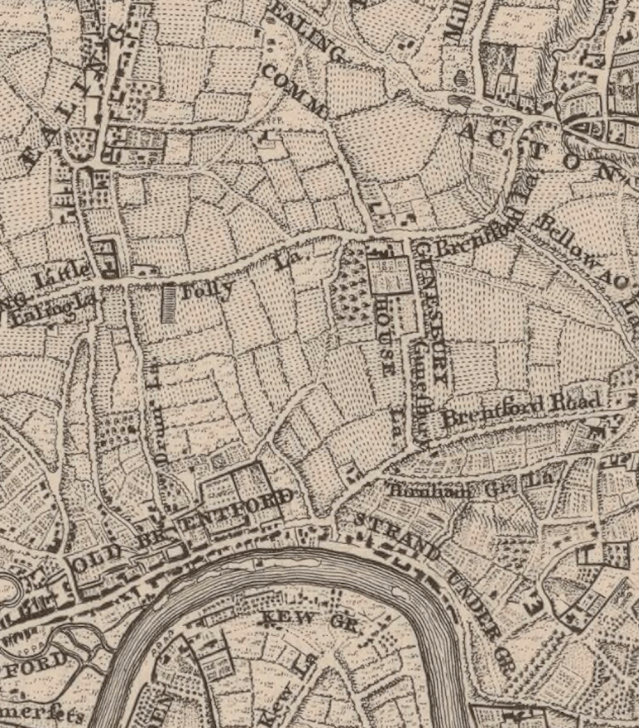

By the time of the Civil War ownership had passed to another prominent lawyer, Sir John Maynard, who commissioned John Webb to build a new Palladian inspired mansion. It had, said a later commentator, “that majestic boldness and simplicity which grace all the works of that excellent artist. It is situated on a rising ground; the approach to it from the garden is remarkably fine. The loggia has a beautiful appearance at a distance, and commands a fine prospect of the county of Surry, the river of Thames, and of all the meadows on its banks for some miles, and in clear weather of even the city of London.” As you can see from the later plan below it meant diverting the road around the site of the new house. Large parts of the new boundary wall survive and have been restored.

Unfortunately, perhaps because he was a lawyer, Maynard’s will was so complex that it took nearly 50 years to get the inheritance sorted, by which time the estate was a bit dilapidated and was put up for sale by his great-grandson, Lord Hobart. In 1739 the house and the surrounding 14 acres were bought for £12,700 by another rich merchant and MP, Henry Furnese [c.1690-1756] who also bought a further 280 acres of tenanted farmland.

The doorway Ito the walled kitchen garden

The house now became a gallery for his extensive art collection and for a venue for concerts, notably by his friend Handel. At this point the gardens had probably not changed much since Maynard’s day as Rocque’s map of 1747 [see above] still shows the footprint of the house with a formal walled garden on a central axis with parterres and rectilinear canals. However, Furnese was also a friend of William Kent and according to Daniel Lyson’s Environs of London (1792) it was he who redesigned the grounds. Certainly payments were made to Kent by Furnese in the course of the 1740s.

To the north of the house a new walled kitchen garden was constructed, as well as a large formal Round Pond, in front of a porticoed Doric Temple built in red brick and white stone which matched the house.

On the southern side, the formal ponds in Maynard’s garden were remodelled into the Horseshoe Pond, the terraces were reshaped more naturally and the formal gardens swept away. On the wider estate farmland was converted into parkland and a lot more trees were planted. A later owner, Alexander Copland, noted in his diary in 1754 that “the grounds were laid out by Mr Brown (Capability)”. As we’ll see shortly he probably had that information from a reliable source, although there’s no documentary evidence to support the claim.

There’s a short description of the garden published in 1761 by Robert and James Dodsley: “On entering the garden from the house, you ascend a noble terrace, which affords a delightful view of the neighbouring country; and from this terrace, which extends the whole breadth of the garden, you descend by a beautiful flight of steps, with a grand balustrade on each fide.” However, the changes might not have been that popular, with Dodsley adding that the gardens “are laid out too plain, having the walls in view on every side.”

For more information on the garden in Furnese’s time see the detailed analysis by Val Bott in The 2019 edition of The London Gardener.

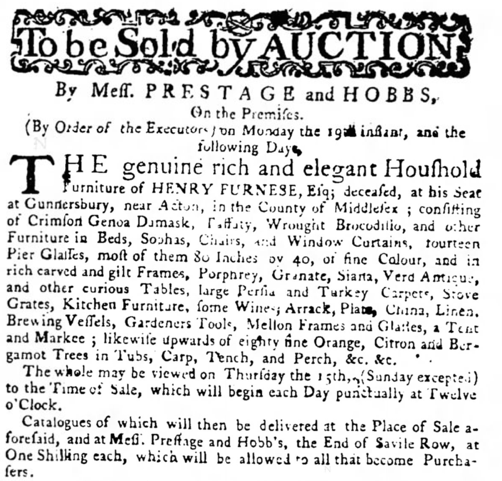

from The Public Advertiser 10th April 1762

After Furnese’s death in 1756 there were again disputes about inheritance and eventually a court ordered that the entire estate be sold. As can be seen from the advert above not only had the house been richly furnished but the gardens must have been well stocked too.

The end of the house and part of the grounds. Image scanned from Gunnersbury Park by Val Bott & James Wisdom

It was bought, after lengthy negotiations from his heirs, for £9000 by the trustees of Princess Amelia [usually known as Emily] one of George II’s daughters. Negotiations had taken place for her to marry Frederick [later the Great] of Prussia but after they fell through she remained unmarried. A recent biographer of George II wrote that “after refusing various offers of marriage from German princes, and having affairs with the Dukes of Newcastle and Grafton, she had settled down to a life of spinsterhood divided between horses, cards and gossip — the more scandalous the better.” The acquisition of Gunnersbury gave her a country retreat, not far from Kew, where George III, her nephew, and hs family spent much of their time.

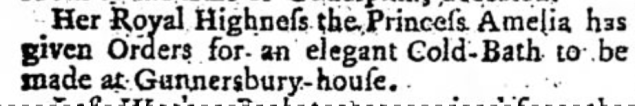

from The Public Advertiser, 10th Feb 1766

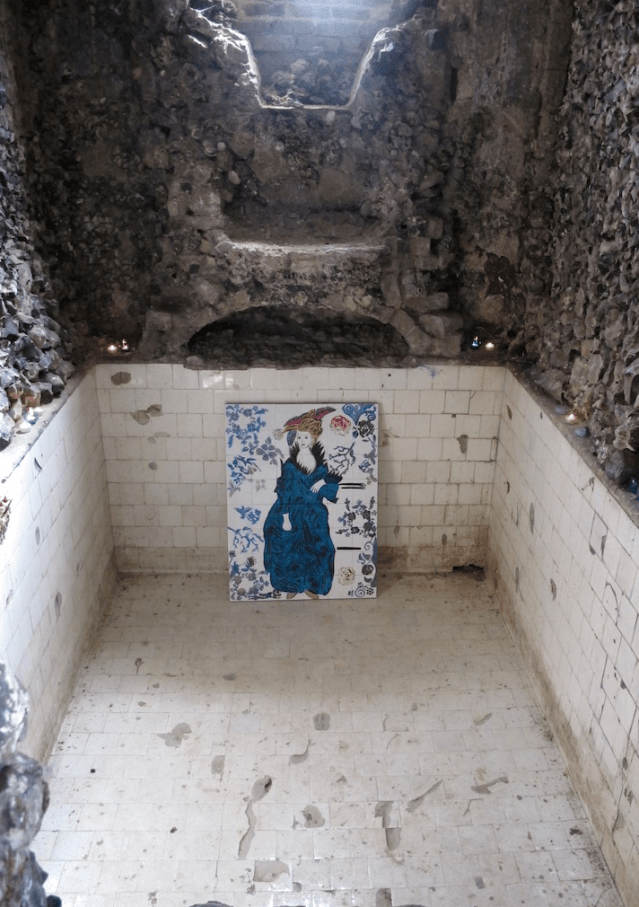

She not only added a chapel to the mansion, and enlarged the estate considerably but if Daniel Lyson’s Environs of London is to be believed spent £22,000 -a small fortune -on additional tree planting and a series of other garden buildings including a grotto and a cold bath which still survives. Lysons added that “the trees in and about the paddock are well grouped, and exhibit some very pleasing scenery. In the pleasure-grounds are several cedars of Libanus, of considerable girth. The whole of the premises consists of about 95 acres, surrounded with a lofty brick wall.”

For more on the cold bath see this article by Val Bott

Princess Amelia’s bathhouse

However, despite the princess’s considerable expenditure the estate was only valued at £18,500 at her death and even that proved impossible for her executors to achieve. Eventually it was bought at auction for about half that by a nabob: Colonel Gilbert Ironsides, former military secretary to Warren Hastings, the Governor General of Bengal, who had just returned from India, wealthy but unwell. When Ironsides moved on, once again the estate proved difficult to sell – perhaps this time because the house was now a century old. However, we’re lucky to have a series of watercolours of the house and gardens done in 1792 by William Payne which are now in the Museum at Gunnersbury.

They show the grounds a few years before the estate was eventually bought by John Morley, who had just sold his floorcloth factory in Chelsea, and was branching out into more speculative business, having already bought and developed a similar, but smaller, estate for housing.

from The Times 14th Sept 1799

from The Times 17th July 1800

It wasn’t long before the end appeared to be in sight for Gunnersbury. 85 “capital Elm and Oak trees…of the largest dimensions” were auctioned, followed by household furniture and garden equipment. The house was demolished and the building material and interior decor put up for auction along with 83 acres of “valuable fertile land…commanding a pleasing prospect of Kew Gardens” .

Morley first offered nine large building plots, then amended his scheme to create 13 smaller ones. So why aren’t there 13 mansions? The simple answer is that, in the end, he only sold plots to 3 people.

Plot 1, of more than six acres next to the road, was sold to a timber merchant named Stephen Cosser who built the first villa [now known as the Small Mansion] on the site, retaining the other existing buildings and adding a house for his gardener. However the three surrounding plots Nos 2, 12, and 13 were sold to a builder named Alexander Copland.

The garden front of the The Small Mansion [remodelled since Cosser’s day]

This meant that Cosser couldn’t expand his holding into the rest of the estate even if he had wished. Plots 3 and 4 at the northern edge, totalling over 12 acres which included the 18thc walled gardens, the Round Pond and the Temple were sold to William Raven, a naval officer. He immediately leased the garden to a nurseryman and had the temple converted into a small house but didn’t build another mansion.

Copland’s villa, later altered to form The Large Mansion

The second mansion was built by Copland who was actually no ordinary small-scale building contractor. He was connected through his mother to Sir Robert Smirke, the architect of the British Museum and was apprenticed as surveyor to Richard Holland, cousin of Henry Holland, the architect and son-in-law of Capability Brown. During the Napoleonic Wars with France he made a fortune by building military barracks with great rapidity, with a workforce of hundreds of men of all trades. He even supplied prefabricated kits to be shipped over to the West Indies. This business was so successful it gave him enough money to acquire all the other potential building plots from Morley and in doing so he salvaged the remains of the estate, holding most of it together.

He now commissioned Robert Smirke, to design a villa – now the Large Mansion – on Plot 2 immediately next door to Cosser’s. I can only presume that the reason it was just a stone’s throw away from his neighbour is because this was the highest piece of ground.

At the same time he was negotiating with Morley over Gunnersbury. Copland acquired the mansion on Piccadilly owned by the Duke of York and converted it into Albany, the prestigious apartment block which still exists today. Later he undertook major contracts such as building the Covent Garden Theatre in Drury Lane [1808-1809] the Royal Military College, Sandhurst (1807–12), all of which proved immensely profitable so that in 1810 he was able to lease the two plots that had been taken by Captain Raven, and almost re-unite the whole original estate. Copland added the small garden behind the Temple, and another by the Horseshoe Pond as well as planting large numbers of trees, and later “modernised’ the kitchen garden with an extensive range of glasshouses and frames.

The garden behind the Temple today

But perhaps Gunnersbury wasn’t grand enough and in 1810 Copland also bought a 1000 acre estate at Langham, Norfolk, although he later gave it up in favour of living back in London. Nevertheless he continued to use Gunnersbury and there are a tantalisingly few brief words about the gardens in 1816 written by John Quincy Adams, then the US envoy in London, and the future president, who attended a cricket match in the grounds. ” I took a walk around the grounds. There are seventy two acres enclosed within the garden walls. The walk round it is at least a mile and a half. The kitchen garden, fruit garden and hot house are upon a very extensive scale, and kept in the highest perfection. I was surprized at finding my walk brought me back again to the house. The Company were just rising from the dessert; and we were entertained with fireworks, rockets, squibs, serpents and the like, over a piece of water in front of the Portico. [the temple by the r9und pond] The grounds are laid out for a view from this Portico in the most beautiful style of English ornamental gardening, with the distant prospect bounded by Richmond Hill and the adjacent country.”

While all this was going on Stephen Cosser’s Small Mansion had been bought by a Major Morrison who was obviously a passionate gardener. John Claudius Loudon visited in May 1826 and wrote up a short account in the Gardener’s Magazine the following year just before Morrison’s demise. “This is a very handsome villa… plain but elegant; a conservatory is attached to it, and in front there is a terrace walk” which said Loudon “would be improved by appropriate architectural terminations, such as alcoves, porticoes, or covered seats.”

He noted Amelia’s “covered bath, supplied by a grotesque cascade, within the building; the basin of the bath forms the reservoir of a jet on a lower level, from which issues a stream led along a pebbly bed, to a considerable piece of water, which in the views from the house occupies with excellent effect what painters call the middle distance. There are many extensive and agreeable walks, through well wooded scenery ; some large and lofty trees, and fine American shrubs.” The Transactions of the RHS in 1835 also noted that Morrison grew pineapples and had imported the “Blood Red Pine”, a variety from Jamaica, although “it is not of such excellence as to warrant the introduction of more than a very few plants in any collection.”

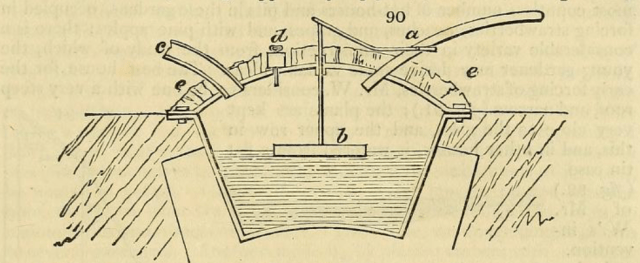

But these features were insignificant compared with what he’s going to see: the kitchen-garden. This “for some years past has excited the great interest, from the superior cultivation of the pineapple, by Mr. William Johnston Shennan. He grows them both in pits heated by tan and dung, without flues or steam-pipes; and also in hot-houses along with grapes. In one house, erected last summer, the bottom heat is supplied by flues and steam jointly,” and here Loudon goes into a lngthy technical description which you can read about here if you’re interested.

Suffice it to say “Mr. Shennan keeps up that powerful degree of heat and moisture, which is evidently the principal cause of the extraordinary, and we might say, unequalled luxuriance of his plants. ” Mr Shennan also great success outdoors with very early peas the seed of which “was obtained from a Frenchman, formerly gardener to General Dumourier, at Ealing”, ” a plantation of early emperor cabbage, most of which were headed, and one plant eminently so, which Mr. S. intends keeping for seed.”He had also “been remarkably successful in growing the orange, of which there is a fine show in the conservatory. With Cactus speciosus, and speciosissimus, Erythrina crista galla, and various other plants, he is also eminently successful.”

Shennan died aged only 40, in 1832 his obituary in the Gardeners Magazine saying that ” as a practical gardener in every branch of his profession, there were few to excel him.”

After Morrison’s death in 1828 the Small Mansion was bought by Thomas Farmer, who was later to commission the Gothic Ruins against the southern wall and probably the gothicising of the ‘Princess Amelia’s’ Bath House, as well as laying out a fernery.

On June 23rd 1828 a description in the Morning Chronicle noted the ‘lawn and pleasure ground laid out with exquisite taste, ornamented with luxuriant shrubs, thriving evergreens and stately timber trees.’ So Gunnersbury was looking up again with the gardens of both villas being well cared for. But things were about to get better still when after the death of Copland in 1834 the estate was bought by Nathan and Hannah Rothschild.

Nathan Rothschild was the founder of the London bank N M Rothschild & Sons, and although he died soon after buying the estate Hannah, their son Lionel (1808-1879) and grandson, Leopold (1845-1917) modified the mansion and transformed the gardens and grounds making it one of the most spectacualr in the country. I’ll look at Gunnersbury under their ownership in next week’s post.

Nathan Rothschild was the founder of the London bank N M Rothschild & Sons, and although he died soon after buying the estate Hannah, their son Lionel (1808-1879) and grandson, Leopold (1845-1917) modified the mansion and transformed the gardens and grounds making it one of the most spectacualr in the country. I’ll look at Gunnersbury under their ownership in next week’s post.

You must be logged in to post a comment.