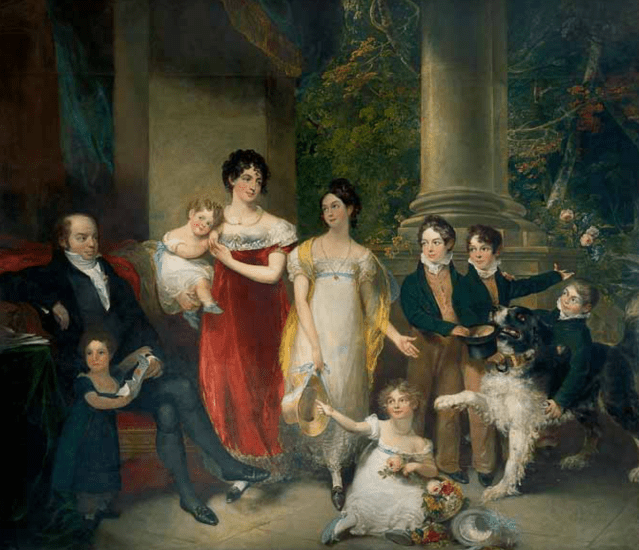

The Rothschild family have long had a reputation as great garden makers but while Waddesdon, Exbury or Ascott might be the sites that immediately spring to mind, it was actually Gunnersbury Park bought by Nathan and Hannah Rothschild for £17,000 in 1835 that was the first to be laid out by the great banking dynasty.

Although Nathan died shortly afterwards, Hannah, their son Lionel, and grandson, Leopold completed the mansion and transformed the gardens and grounds, notably creating one of the earliest Japanese gardens in Britain. Together with their skilled and creative staff they made Gunnersbury one of the most celebrated gardens of its day.

The Orangery by the Horseshoe Pond

As usual the photos are mine unless otherwise acknowledged

The Rothschilds were an international family. The founder of the dynasty Mayer Amschel Rothschild had five sons who established branches of the family’s business in five major cities: Paris, Frankfurt, Vienna, Naples and London .The brothers were all granted the title of Baron by the Emperor of Austria in 1822 although Nathan, who headed the London business, chose not to use it and so did not request official recognition of his foreign title in Britain. However, in 1838, two years after his death, Queen Victoria authorised its use and thereafter Hannah is often referred to as Baroness de Rothschild.

The couple sought advice from John Claudius Loudon about improvements to the approach to the house and commissioned Sydney Smirke [Robert Smirke’s younger brother] to re-model the mansion. He also designed a new stable block, tucked away almost out of sight, beyond their neighbour’s south wall although this was not completed until after Nathan’s death. Meanwhile the farm buildings on the west side of the estate were converted into a thatched ornamental farm and a herd of prize winning cattle was established there.

Loudon later included lots of references to specimen trees at Gunnersbury in his encyclopaedic account of British trees and shrubs, Arboretum et fruticetum Britannicum (1844), where he also notes the estate’s innovative ways of growing and propagating them.

One of the stable blocks, now sadly in a desperate state

At his death Nathan was the richest man in Britain, but, as Diana Davis points out, Gunnersbury was never a typical rich man’s estate and instead remained just a large [if luxurious] Regency villa and very much a private retreat and family home. Nevertheless for next 14 years Hannah also entertained royalty and the aristocracy with a number of lavish fêtes champêtres, showcasing the gardens. When Disraeli attended one of these in 1843, it impressed him as “a most beautiful park and a villa worthy of an Italian Prince, though decorated with a taste and splendour which a French financier in the olden times could alone have rivalled . . . [with] beautiful grounds, temples and illuminated walks.” He is thought to have modelled one of the venues in his novel Tancred [1847] and another in Endymion [1880] on what he saw at Gunnersbury.

Hannah also continued to improve the estate, notably commissioning Smirke to design the Orangery next to the Horseshoe Pond and also to add a conservatory.

[For more on this see Davis’s article “A rite of social passage: Gunnersbury Park, 1835–1925, a Rothschild family villa” in the Journal of Modern Jewish Studies, which is available free via academia although you will need to open an account], and also volume 1 of Neil Ferguson’s The House of the Rothschilds, which is also available on. academia

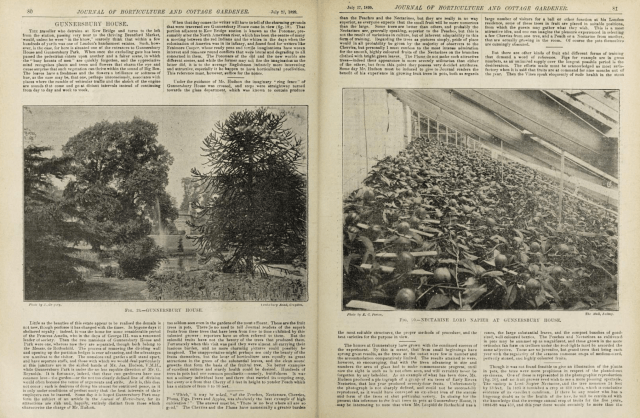

Hannah took a keen interest in the garden employing talented gardeners who helped develop the estate’s reputation for horticulture, especially for growing fruit of all kinds notably pineapples. Among them was George Mills who had from 1833 been gardener to Alexander Copland, the previous owner. According to his obituary notice in the Journal of Horticulture, at the time of the sale in 1835 “Mr. Mills had a house of magnificent Muscat of Alexandria Grapes at Gunnersbury, and so much were the purchasers pleased with the appearance of this house that they resolved to continue Mr. Mills in the post of gardener.” Mills is known for writing An Improved Mode of Cultivating the Cucumber and Melon, and The Cultivation of the Pine-apple, both of which were dedicated to “the late Baroness de Rothschild”, and he stayed working there for twenty years, until his retirement in 1853.

You get some sense of the scale of the glasshouses from a newspaper article on 5th June 1849 reporting that a hailstorm had broken no less than 3940 panes of glass. Some of them, including the span-roofed vine house, were inherited from Copland but it’s clear that the Rothschilds had continued to expand and improve the range.

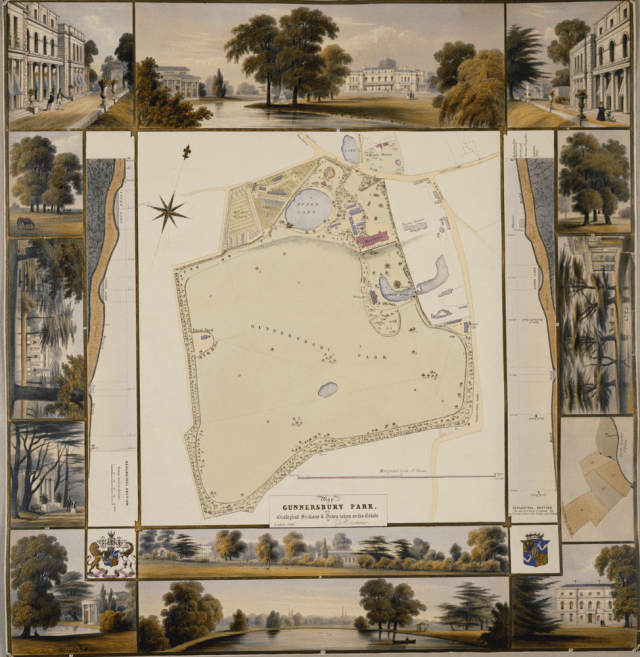

Some of this is revealed in the splendid coloured plan drawn in 1847 by a Major Kretschmar which also has a series of vignettes of the landscape to bring the cartographic details to life. Hannah died in September 1850 while playing with her grandchildren, and rolling down the lawns in front of the house. The estate passed to her eldest son Lionel who, with his wife Charlotte, continued the good work in the garden so that by 1855 Gunnersbury was ‘justly celebrated’ for the ‘magnificent cedar trees’ and introduction of rare conifers.

Some of this is revealed in the splendid coloured plan drawn in 1847 by a Major Kretschmar which also has a series of vignettes of the landscape to bring the cartographic details to life. Hannah died in September 1850 while playing with her grandchildren, and rolling down the lawns in front of the house. The estate passed to her eldest son Lionel who, with his wife Charlotte, continued the good work in the garden so that by 1855 Gunnersbury was ‘justly celebrated’ for the ‘magnificent cedar trees’ and introduction of rare conifers.

William Forsyth became their head gardener and he maintained Gunnersbury’s reputation for fruit. In the early 1860s Charlotte was honoured with a new variety of large-fruited pineapple being named after her, which was introduced by Benjamin Williams of Holloway, and is still in large-scale commercial production.

As we’ll see Gunnersbury has been the subject of almost innumerable articles in the gardening press. One of the earliest was in The Cottage Gardener in 1855 describing how exotic flowers filled the house for the wedding of Leonora, Lionel and Charlotte’s eldest daughter to her French cousin Baron Alphonse. The author then toured the garden, commending Forsyth, “as one of the go-ahead sort, best qualified to carry out all modern and improved systems.”

The Gothic Boathouse Tower

Hannah had taken the estate’s acreage from 75 to 109 [as well as buying land in the country at Mentmore and laying the foundations for others in the family to build in what became known as Rothschildshire] and Lionel continued to buy land when it became available. In 1861 he added a former clay pit and pond known as Cole’s Hole and the neighbouring redundant tile kiln. These he converted into the Potomac Lake and Gothic Boathouse, adding a Pulhamite Rockery and picturesque planting of shrubs, bamboos and grasses.

He also acquired the neighbouring Brentford Common Field using it partly as pasture for his racehorses, while the existing farm was once again remodelled this time in the fashionable gothic style.

William Forsyth retired in 1870 and Gardeners Chronicle carried a report of a visit just before he did so. Once again its the scale of the operation that commands attention, with, for instance, “a Peach wall permanently covered in with glass, exceeding 400 feet in length” as well as “a nice compact group of forcing houses filled with miscellaneous collections of ornamental foliage plants, grown to a size suitable for the indoor decoration of the town mansion” nor was it “necessary to offer a word on the Pineapple growing at Gunnersbury, because Mr. Forsyth has long proved himself an adept at this kind of work.”

“The front of the mansion here overlooks a scene of beauty, suggesting calm and repose as the eye glances over the whole. Every inch of grass is kept constantly watered with the hose. The lawn is consequently amidst all the surrounding drought, the “greenest of the green.”

With Forsyth’s retirement care of the gardens passed to John Richards, formerly of Grimston Park near Leeds, and in 1880 Gardeners Chronicle carried a lengthy description of the garden stressing his skills.

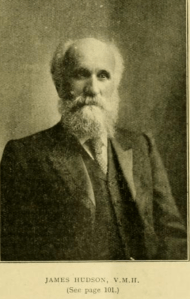

Meanwhile Thomas Farmer who bought the Small Mansion appointed James Hudson as his gardener in 1876. Hudson was to become a major influence on the development of Gunnersbury over the next nearly 40years. Both he and Richards were keen exhibitors and regular prizewinners [see for eg GC May 1880]

detail from Ordnance Survey 6″ map London Sheet VI.SW

Revised: 1891 to 1894, Published: 1894 to 1896. The two properties are clearly demarcated

Lionel Rothschild died in 1879 and his son Leopold took over. Ten years later after Farmer’s death his daughter and heir put the Small Mansion up for sale giving Leopold the opportunity to reunite the original Maynard landholding. He snapped it up.

The wall between the estates was demolished. The living areas of the small mansion were used as guest accommodation while the cellars were given over to mushroom growing. Crucially for the estate’s horticultural reputation James Hudson was kept on as part of an enlarged garden team. Gunnersbury was about to reach its apogee.

By now almost every issue of the major horticultural magazines carried a mention of Gunnersbury, and recorded the many prizes its plants and produce gained at shows and exhibitions. It’s clear from them that Hudson took the lead role. He was to become one of the first recipients of the Victoria Medal of Honour established by the Royal Horticultural Society in 1897 to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee.

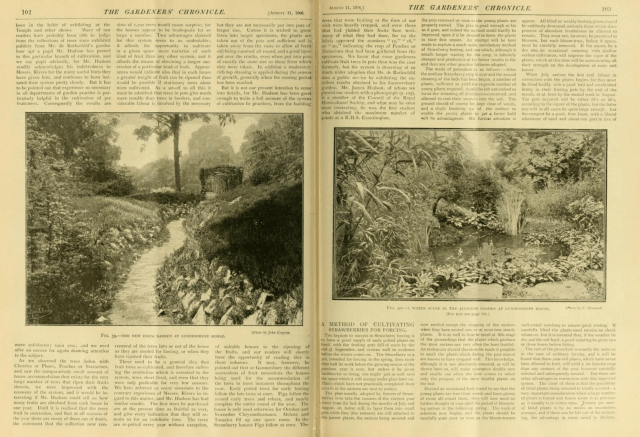

One innovation was the way that roses were trained over frameworks to form basket shapes, a technique which has been reintroduced by the current garden team. New glasshouses continued to be added, including several for forcing fruit. These new houses, according to Gardeners Chronicle in May 1898 ” were really orchard-houses, that is, they provide for the forcing of standard trees in pots, without the trellises or trained trees common in most fruit houses. When visiting the gardens a fortnight ago the Nectarine fruits in the earliest house were ready for the table.” [see image below] There were ripe figs in February, and grapes by April. A report from 1900 also notes that paw-paws had been grown from seed and were already ten feet tall and fruiting.

There was a fine collection of aquatic plants including recently introduced hybrids of water lilies from Latour-Marliac and a tank installed in one of the hothouses “where the water will be heated, and blue Nymphaeas cultivated.” It was there that Hudson raised a new blue waterlily that was given his name. One of the earliest cultivars of the gigantea group it was for decades the largest blue waterlily available although now it is very hard to find commercially.

Pocket-book of Thomas Hobbs

The Journal of Horticulture carried a 3 page spread on the garden in 1899 which is worth reading if you want to know more detail. You can also get a sense of the vast scale of the gardening operation from the pocket book of Thomas Hobbs, one of the gardeners in the 1890s which has been preserved in the Rothschild Archive

The magazine also reported that “some of the pretty nooks are worked out from Mr. Leopold de Rothschild’s own designs, as, for example, the pretty little country Swiss Garden, with sundial in the centre, the idea for which was obtained in a quiet Swiss retreat” although “more often the new gardens result from conferences with Mr. Hudson, who always superintends every detail of the work.” (I suspect this Swiss Garden is the one called the Round Garden in the postcard below but I’ sure someone will correct me if I’m mistaken.)

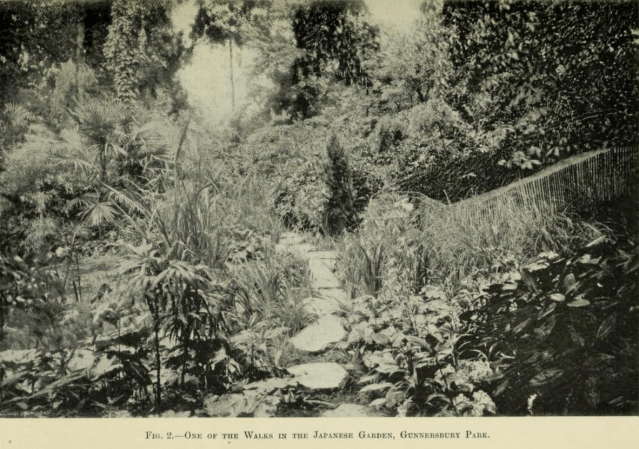

However their great creation was the Japanese garden which was laid out near the stable block by Hudson in 1900-1901. Surrounded by a series of bamboo fences and gates it included a bamboo avenue, using thirty different species and varieties, and a bamboo bridge. Complete with an elegant tea house as well as lanterns lit with electricity, stepping stones and an island with dwarf conifers, it was widely publicised in the horticultural press, and caused a sensation. Although there had been Japanese exhibitions in London in the previous 20 years the great boost to creating Japanese Gardens in Britain did not occur until after the 1910 Great Japan Exhibition at White City, so once again Gunnersbury was ahead of the curve. However although it was called a Japanese garden the emphasis was definitely on Japanese plants rather than authentic Japanese design.

James Hudson 1906

There are several more lengthy articles in the horticultural press. For example The Gardening World carried one in December 1903 with a detailed description of the many greenhouses [almost too many to count let alone list here!] but which also shows that Hudson and Rothschild had started gardening on the roof too, ” a phase of gardening which is seldom seen, and is here carried out. very handsomely.”

Gardeners Chronicle carried another in 1906 describing the garden in detail and showing James Hudson still going strong aged 64. He eventually died aged 91 in 1932.

But even as the estate was flourishing and continuing to expand the signs of its end were in sight. London was spreading and suburbia had begun to approach and encroach on Gunnersbury.

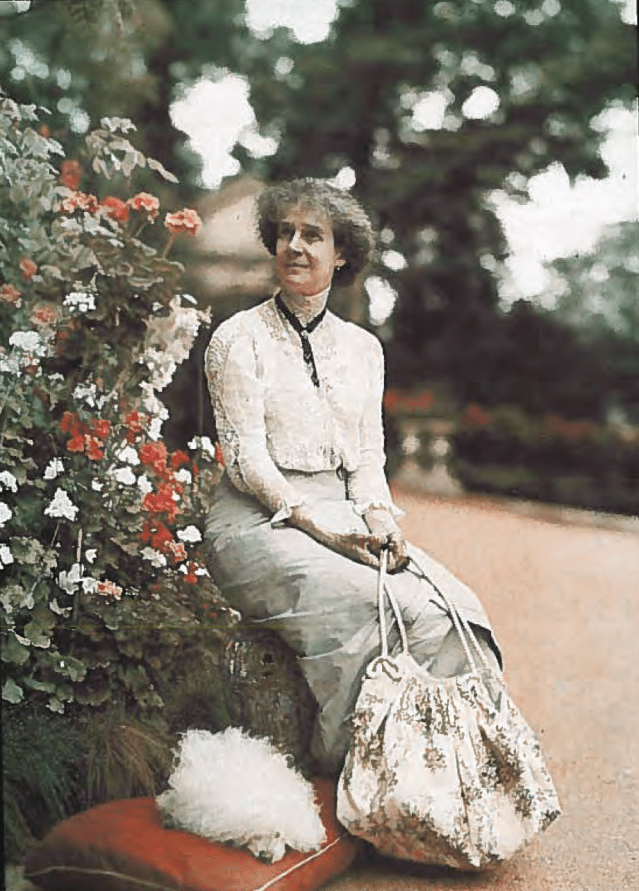

Marie de Rothschild c.1910 on the terrace

from The Colours of Another Age on the Rothschild Archive website.

Leopold de Rothschild died in 1917, and his widow Marie and her son Lionel must soon have decided to sell up and move on . The final straw seems to have been plans, initially proposed in 1914, for the Great West Road [now the North Circular] which was to run parallel with the long eastern boundary wall although this wasn’t actually begun until 1922. Follow this link for more on the building of the Great West Road

By 1920 negotiations started with Ealing Council to buy 74 acres of the grounds for a park. There was lot of local opposition and the start of a 5 year campaign about whether or not to buy Gunnersbury for public use. [I tried to follow this through newspaper reports but it was so complex that writing a proper account would make as suitable topic for an MA if not a PhD!]

By this point Hudson had retired and been replaced by one of his foremen Arthur Bedford, but despite his evident skill it was reported that “Gunnersbury has lost much of its pre-war glory.” Lionel who was later to describe himself as ‘a banker by hobby but a gardener by profession’ had bought Exbury in the New Forest and used Gunnersbury as a base to grow plants for the new garden there. For example “a collection of seedlings, raised from the seeds collected by many well-known Chinese and Thibetan collectors of recent years[were] destined to be planted in the recently acquired property of Mr. Rothschild in Hampshire, where the soil and climate are admirably suited for the growth of these rare shrubs, particularly the Rhododendron family.”

From The Sphere 25th April 1925

From the Callander Advertiser – Saturday 20 February 1926

Eventually at the very end of 1925, Gunnersbury was bought by two adjacent local authorities – Ealing and Acton for £125,000, ironically funded by a mortgage from the Rothschild bank, on the understanding that houses would be built along two main roads nearby to fund repayment. However the philanthropic streak in the Rothschilds put restrictive covenants in place to ensure that the rest of the estate could only be put to a beneficial public use and not developed as housing.

Eventually the park was managed by a joint committee of Ealing and Acton together with the boroughs of Chiswick and Brentford. The grounds immediately around the houses continued to be managed as formal gardens but £7000 was spent transforming it into a public park, including buying the Rothschild’s machinery, leasing the fields for grazing, employing a team of 36 staff, buying 100 benches, drinking fountains, and setting up facilities for golf, tennis, football, cricket as well as bowls and fishing. Tea rooms were set up in both the stables and farm buildings.

84 candidates applied for the job of superintendent and Sydney Legg, previously head of the parks in Margate, was appointed on a salary of £400p.a and free accommodation. When Margate heard the news they upped his pay to £450 and promised £500 the following year. Mr Legg changed his mind and the job was then offered to William Armstrong who had been parks superintendent at Coatbridge in Scotland.

from The Daily Mirror 7th April 1925

The new park was opened in 1926 by Neville Chamberlain then the Health Minister in front of huge crowds. The following year the Rothschild’s mansion became a museum.

With the reorganisation of local government Gunnersbury became jointly owned and funded by the London Boroughs of Ealing and Hounslow. Like many other great urban parks it fell on hard times in the second half of the 20thc. There is no endowment fund, so the cost fell on the council tax payer and when one borough cut contributions, the other one had to do the same, with very damaging results. Estate buildings fell into disrepair with many put on the At Risk Register. Being under divided management didn’t help but the fact that it’s a Grade II* , nationally important, registered landscape has helped prevent a total disaster.

The park is really well used and there is an active Friends group founded in 1981. They pressured the authorities to prepare a comprehensive plan for the park’s future and there have been a series of reports and surveys since then attempting to reverse the decline. You can follow the long and often sorry saga on the Friends website including the current ten year plan which covers the years until 2026. A lot of restoration work has been carried out, thanks in large part to a £21m grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund in 2014, although there remains masses more to do and, as elsewhere, income generation schemes have proved controversial, especially as the museum and the park itself cost just under £2.5 million a year to run.

The estate is now run by the non-profit Gunnersbury Museum and Park Development Trust, so while the picture still isn’t that rosy there is cause for a little optimism because as Owen Thomas, head gardener to Queen Victoria said “It matters little at what season of the year one visits Gunnersbury, there is sure to be something to admire.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.