August is traditionally the silly season in the media, so in keeping with that the next few posts are going to look at garden-related humour, beginning today with the work of Reginald Arkell.

August is traditionally the silly season in the media, so in keeping with that the next few posts are going to look at garden-related humour, beginning today with the work of Reginald Arkell.

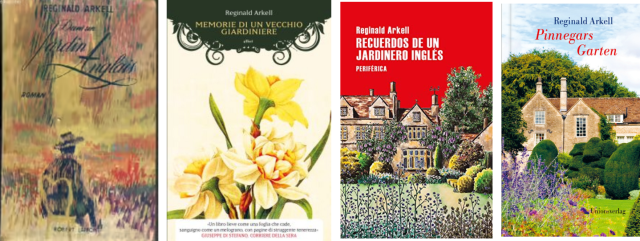

I can hear the muttering already. Who on earth was he? Unless you’ve read his work the name Reginald Arkell probably doesn’t ring many bells today, but until his death in 1959 he was a well-known and successful editor, playwright and later screenwriter, television commentator, lyricist for musicals, novelist and poet. He was also a keen gardener and amongst his works were a series of books of comic garden verse [I hesitate to call them poetry] including Green Fingers and Other Poems and a comic novel Old Herbaceous all of which were in their day best sellers.

As the publishers blurb says: “Anyone who loved the England of Goodbye Mr. Chips and Mrs. Miniver will love Mr. Arkell’s England, too. But the central character is not peculiar to the English countryside; wherever there is a garden, there you will find Old Herbaceous.”

Let’s see if his humour still appeals…

From Daily News , 11th March 1931

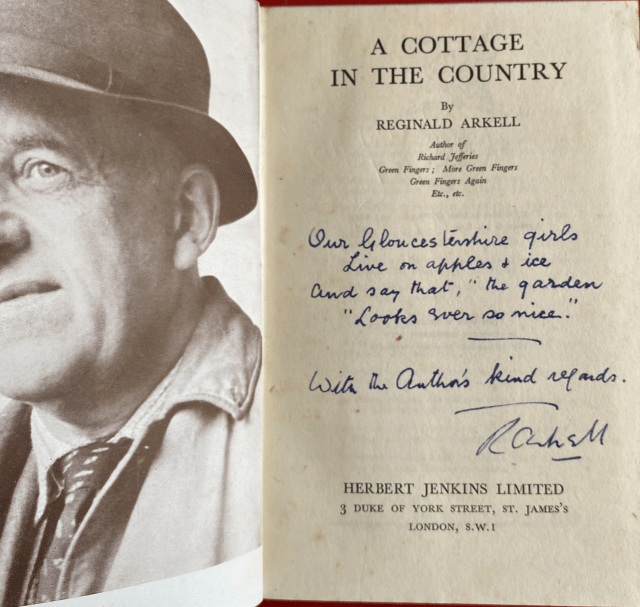

Arkell was born in Lechlade in the southernmost corner of Gloucestershire in 1882, discovering his talent as a writer at Burford Grammar School. He became a journalist, but as I discovered from British Newspaper Archives, he soon developed other talents. He wrote publicity material for the London, Brighton and South Coast railway company, in “his usual bright, picturesque and interesting style, so different from that of the modern guide book.” He organised concert and other events, wrote librettos and songs for amateur musical productions in which he often acted as well.

Although he worked as a sub-editor on London Opinion, in the years before World War 1 articles, stories and poems began to appear in other titles as diverse as the boys magazine, The Captain, The Novel Magazine which specialised in pulp fiction and Country Life. His first play Columbine “a pretty little fantasy” was put on in Hanover Square in 1911, and went on tour with his wife Elizabeth, who he had married in 1912, as the lead. A royal command performance took place in 1920 and later the play was adapted for radio.

from the Wilts and Gloucestershire Standard. 19th Sept 1914, with the. first couple of verses

On the outbreak of war in 1914 he enlisted in the Yorkshire Light Infantry, serving as a subaltern. While some of his poetry suggests he saw active service he was certainly still extremely busy writing throughout the war years.

Like most of his contemporaries he was very patriotic, and a long poem he wrote on the outbreak of war “Business As Usual” was regularly performed on the London stage before the start of plays .

In 1916 he published All the Rumours a book of comic anti-Kaiser ditties and the following year The Bosch Book. It was one of a series of “Illustrated humorous volumes” with other contributors including H.L.Bateman, Heath Robinson and Alfred Leete who designed the famous Lord Kitchener poster for London Opinion .

In 1916 he published All the Rumours a book of comic anti-Kaiser ditties and the following year The Bosch Book. It was one of a series of “Illustrated humorous volumes” with other contributors including H.L.Bateman, Heath Robinson and Alfred Leete who designed the famous Lord Kitchener poster for London Opinion .

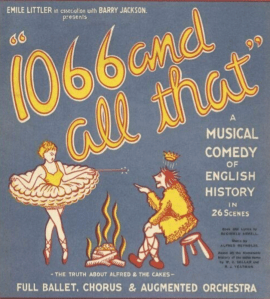

After the war Arkell began to work for Newnes, the publishing house, setting up or editing a number of magazines for them including Men Only and in his spare time continued to turn out articles, poems, songs and comic plays, many of which proved popular on the London stage. Later he moved into radio, television and film work with his most successful effort probably being the 1936 adaptation of Sellar and Yeatman’s spoof history book 1066 And All That for the stage and later the screen. [You can just about make out his name in the bottom right corner of the poster from the V&A collectiion]

After the war Arkell began to work for Newnes, the publishing house, setting up or editing a number of magazines for them including Men Only and in his spare time continued to turn out articles, poems, songs and comic plays, many of which proved popular on the London stage. Later he moved into radio, television and film work with his most successful effort probably being the 1936 adaptation of Sellar and Yeatman’s spoof history book 1066 And All That for the stage and later the screen. [You can just about make out his name in the bottom right corner of the poster from the V&A collectiion]

Although he spent much of his time in London he definitely remained a countryman at heart. In 1931 he wrote A Cottage in the Country, his first real venture into describing his love of the countryside, especially the borderlands of Gloucestershire and its neighbours Wiltshire and Oxfordshire,

Although he spent much of his time in London he definitely remained a countryman at heart. In 1931 he wrote A Cottage in the Country, his first real venture into describing his love of the countryside, especially the borderlands of Gloucestershire and its neighbours Wiltshire and Oxfordshire,

He bought a house in Marston Meysey, just over the Wiltshire border from Lechlade and eventually moved there full-time. Arkell and his wife were keen gardeners and this love of all things horticultural often spilled over into his writing.

All the poems are scanned from Collected Green Fingers

The first of the Green Fingers series of garden verse came out in 1934 to very positive reviews. The humour in Arkell’s verses is gentle but now sadly seems rather dated, yet it went through 25 editions. The cartoonish illustrations by Eugene Hastain are equally dated but remain amusing, and are vaguely reminiscent of those in Capek’s A Gardeners Year published in 1931 [See this earlier post if you want to check]

The first book was followed by three more: More Green Fingers, Green Fingers Again,—And a Green Thumb, which between them sold over 200,000 copies. His publisher claimed “No other books of light verse have ever made so wide an appeal; none have so cleverly epitomised the gardener’s lot from every imaginable angle; the beauty of it, the wonder, the exasperation and the humour.” They were “a pocketful of sunshine for dull days.” A selection of Arkell’s favourites were later re-issued as a compendium under the title Collected Green Fingers in 1956, while many individual pieces appears in anthologies today including The Everyman Book of Light Verse.

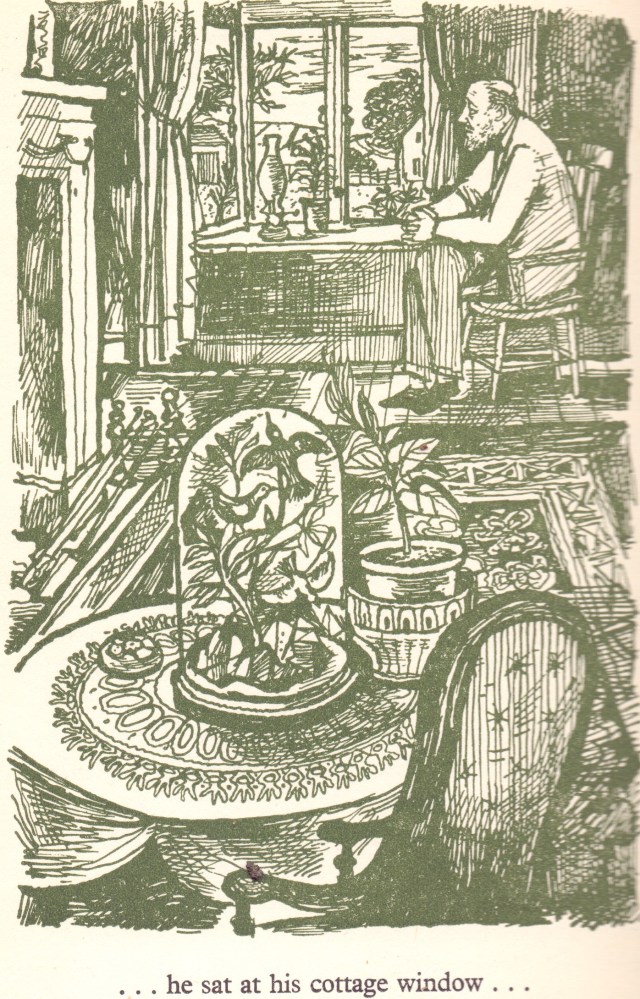

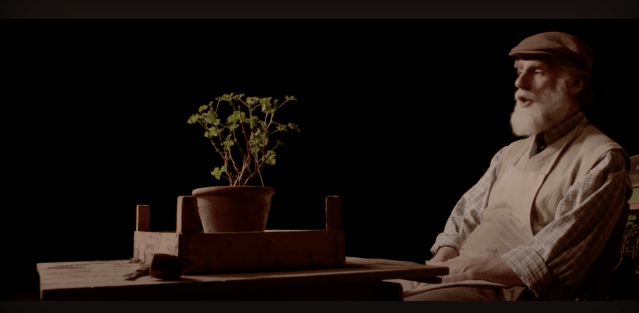

The black and white images below come from a edition of Old Herbaceous with illustrations by John Minton which can be found on Archive.org

Arkell’s output did not slow down as he got older and in 1950 he published what must surely be his best and most enduring work Old Herbaceous. It is the story largely told through the reminiscences of a long-serving head gardener on a small country estate during the years that saw the transformation of English gardening from the grand scale, easy finance and cheap labour of the Edwardian to a more difficult and much-diminished one following the social and economic changes brought about by two world wars.

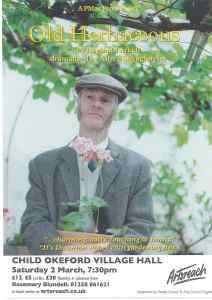

It is by turns poignant, sharply observant, amusing and insightful and according to one recent review it is “a classic British novel of the garden, with a title character as outsized and unforgettable as P. G. Wodehouse’s immortal manservant, Jeeves.”. It had wide popular appeal for its sympathetic portrayal of the old man and in 1979 it was turned into a one-man show by Alfred Shaughnessy which is still being played. There’s a nice article in the Guardian about one production by Peter McQueen the actor who starred in it and how he took the show on the road.

Old Herbaceous was unceremoniously left as a baby on the doorstep of Mrs Pinnegar, “a kindly soul, with six children of her own” and ” unofficial midwife and friend of all families “so she knew the baby wasn’t ‘local’. However, “being a practical woman, the cowman’s wife picked up the parcel the fairies had brought her; christened it Herbert, after an uncle who was killed in the Crimea, and set about her Monday’s wash. When you had six of your own, one more didn’t matter.”

Old Herbaceous was unceremoniously left as a baby on the doorstep of Mrs Pinnegar, “a kindly soul, with six children of her own” and ” unofficial midwife and friend of all families “so she knew the baby wasn’t ‘local’. However, “being a practical woman, the cowman’s wife picked up the parcel the fairies had brought her; christened it Herbert, after an uncle who was killed in the Crimea, and set about her Monday’s wash. When you had six of your own, one more didn’t matter.”

When Herbert went to school the village schoolmistress saw that he was interested in wild flowers and she took him in hand, taking him on walks and teaching him about them “so that, of young Herbert it began to be said that what he didn’t know about wild flowers wasn’t worth knowing.”

Eventually a week before the annual village flower show she encouraged him to enter. He chose to pick water plants from the local canal-side but even aged 11 “he had to learn the lesson that comes to every gardener: all the flowers are never out at the same time. Either you are too late or you are too early. The flowers you grow today are never so lovely as the flowers you grew yesterday and will grow again tomorrow.” As a result “the gardener is a frustrated being for whom flowers never bloom at the right moment. … It is all very sad, and how gardeners manage to keep going in the face of such adversities is one of those things that no fellow will ever understand.”

Herbert was depressed when he saw the other entries were all bigger and more impressive than his, but when he turned to the judges – “that imposing collection of autocrats” – he saw next to them “the most lovely, laughing lady he had ever seen. Almost a girl she was; not a day older than eighteen — young Herbert stood in the centre of the tent with his mouth wide open and promptly fell in love, for ever, and ever, amen.”

To his immense surprise he wins first prize and is handed it by the same lovely lady. “Do you know why I’ve given you the first prize?” “No, miss,” said young Herbert. And if ever he spoke the truth, it was then. “Because you picked water flowers instead of grabbing the first things that came and mixing them up anyhow. You must help me with my garden one of these days. . . . Now, run along. . . .”

Herbert hated the way that farmers waged war on wild flowers calling them weeds and vowed he’d never ever work on a farm, although there was little else by way of employment in the countryside then. When the time came to leave school and start work “it was customary for boys to go along to the Vicarage and have a nice friendly little chat … the Vicar asked what you were going to do and you mumbled that you were going into the stables up at the farm” but when it was Herbert’s turn for the interview something went awry.

“In the first place, the Vicar was not alone. Sitting in an armchair, reading a copy of a magazine, was the lady of the flower show. By this time, everybody knew that she was going to marry young Captain Charteris, who had bought the Manor, and that the wedding was taking place almost any day now.” The vicar was aghast when Herbert said he didn’t want to work on a farm but “the lady sat there, laughing at the pair of them, until the tears ran down her cheeks.” Then remembering he was the boy who had won the prize for wild flowers at the show she asked “How would you like to come to the Manor, and help me with my new garden?” For Herbert “The gates of Paradise opened widely on well-oiled hinges and then, as slowly, closed again.”

Then Arkell comes out with one the gentlest but effective put-downs imaginable.

“Really, Charlotte,” said the Vicar, “I wish you wouldn’t interfere. What do you know of our rural problems? You’ve only been here two minutes.” “If it comes to that, Vicar,” was the surprising reply, “what do you know about the Garden of Eden? You were never there at all.”

Herbert goes to work as one of three apprentices to head gardener Mr Addis who was “a fair man” and “getting on, but he still had a lot of kick left in him. Leaning heavily on tradition, he allowed no unfortunate experiments to shake his authority.” At this point Arkell reminds us that “English gardens had achieved a restful homeliness lying about midway between the elegance of the past and the professional competence of the future. Vistas, parterres and classical shrines had faded into the landscape. The modern marvels of the Chelsea Flower Show were yet to come. Life was placid, unimaginative and rather pleased with itself. There were no new worlds worth conquering. No urge, no rush, no worries. The sort of world that bred the sort of man Mr. Addis was proud to be.”

Herbert loves the garden and often works unpaid overtime and was sometimes spotted by the lovely lady – now Mrs Charteris – who knew she wasn’t a very good gardener herself. They become as friendly and mutually respectful within the terms of employer and young employee as was acceptable in that day and age, and much of the book is about the interactions between the two.

Arkell writes about Herbert Pinnegar with affectionate humour, in the process detailing much of the everyday business of first a gardener’s boy, then Mr Addis’s assistant and finally as Head Gardener to Mrs Charteris. His skill is acknowledged and the garden blossoms under his perfectionist care. He is nicknamed Old Herbaceous by his own apprentices and grows in confidence until he becomes the most esteemed flower-show judge in the county. He shows real dedication and affection for Mrs Charteris, magicking up surprises for her – such a supply of delicious strawberries in April – which obviously required months of careful and secret planning. On another occasion after she returns from a trip to the south of France she described some of the plants she has seen there, especially “the fabulous morning glories, all blue, so blue, in fact, that once you had seen them you could never be happy again”.

“For a countryman Bert Pinnegar acted promptly.” He contacted the director of Kew and begs some seeds which he grows in secret.

As they come into flower he asks to see her in one of the greenhouses. She appears ready “for whatever tale of woe he might have to tell” but instead he points upwards. “Mrs. Charteris raised her eyes, and, seeing the drift of blue blossom, gave a little cry of sheer happiness. Once again she felt that tug at the heart, a kind of suffocation that almost hurt. Once again she was drifting over a blue sea, under a blue sky, into a lovely land of blue nothingness. . . .”Oh, Pinnegar,” she said. “How kind of you — how very, very kind!”

It’s been translated into at least 4 languages

Old Herbaceous is full of little stories like that, and is also sprinkled generously with little bits of gardening wisdom, and philosophical comments on life. One of my favourites is Herbert looking out of his window and reflecting on his life and work: “You planted a tree and you watched it grow; you picked the fruit and, when you were old, you sat in the shade of it. Then you died and they forgot all about you — just as though you had never been. . . . But the tree went on growing, and everybody took it for granted. It always had been there and it always would be there. . . . Everybody ought to plant a tree, sometime or another— if only to keep them humble in the sight of the Lord.”

Mind you that’s not as amusing as Herbert’s comments to “an earnest young priest who had stopped to ask the old man if he knew what Good Friday was all about. “Good Friday?” came the reply. “Good Friday be the day when the Almighty reckons we ought to get our ‘taties in.”

Herbert pushing Mrs Charteris around the garden for the last time before she leaves

But of course the time comes when both main characters are getting older and Mrs Charteris decides she has to sell up and move to a hotel in Torquay. The new owners apparently want to replace Herbert Pinnegar but he doesn’t want to retire and spend his days in his cottage doing nothing but look out of the window.

But of course the time comes when both main characters are getting older and Mrs Charteris decides she has to sell up and move to a hotel in Torquay. The new owners apparently want to replace Herbert Pinnegar but he doesn’t want to retire and spend his days in his cottage doing nothing but look out of the window.

Unfortunately there seems little option. But, of course there is, although I’m not going to spoil the story by telling you how it ends, although it is very moving.

All I can suggest is that you read it yourself. It’s a short book – only 160 pages long so it’s readable in one sitting – and available for free on-line. It’s definitely worth the effort.

Reginald Arkell retired from Newnes in 1954 but continued to write and appear on television as a commentator on what his obituary termed “light subjects” until his death in 1959.

Reginald Arkell retired from Newnes in 1954 but continued to write and appear on television as a commentator on what his obituary termed “light subjects” until his death in 1959.

His papers are now in the Theatre Archive, at the V&A but they are limited to his stage works and libretti, with little mention of his journalism or books and none at all of his love of gardens. I’m sure he’d have been able to pen a verse about that omission.

But let me leave you with the epilogue to his collected garden verse…I’m sure that Herbert Pinnegar himself would have agreed!

You must be logged in to post a comment.