A tiger lily made of tigers

Years ago, in another life, I was head teacher of a school in north London. Our playground was on the site of the birthplace of Edward Lear, so the children and I got to know a lot about him when the centenary of his death occurred in 1988. I hope his work is a good subject for another post about garden-related humour.

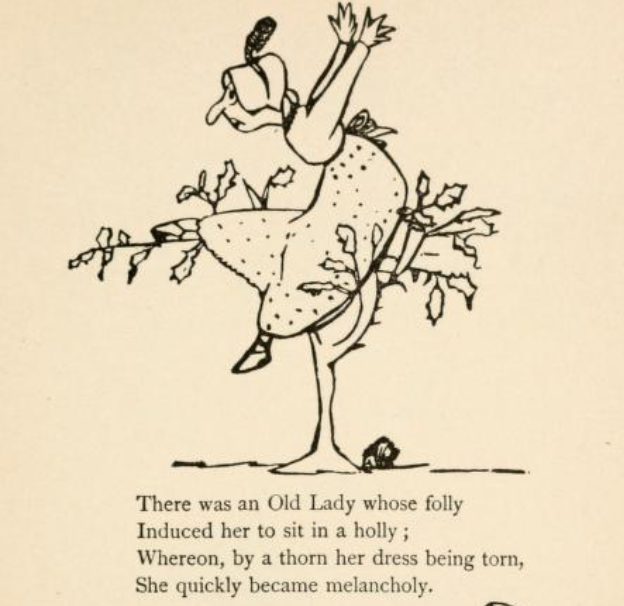

Most people will know Lear as the wonderfully eccentric writer of limericks and nonsense verse where he invented characters such as the Quangle-Wangle, the Pobble Who Had No Toes and of course the Owl and the Pussycat. What is perhaps less well known is that he was a gifted artist, especially of landscapes and natural history. I wrote about him on here over ten years ago but thought this would be a good opportunity to return and write about his onsense botany.

The images, unless otherwise acknowledged come from the 1894 edition of Lear’s collected nonsense.

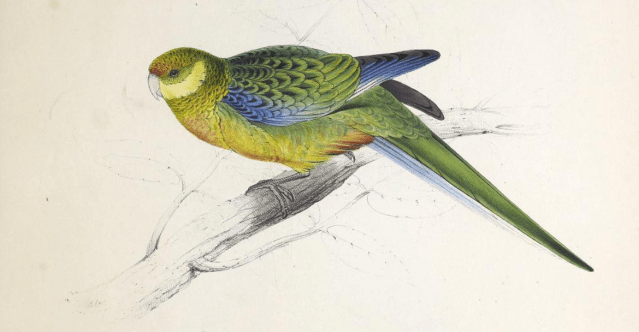

Lear began drawing commercially at a very early age and his earliest flower paintings, which date from the late 1820s, are probably as good as any botanical illustration of that time. Unfortunately for botanical art he soon opted to take a greater interest in natural history, especially birds. This may have been because he met the American ornithologist and bird painter John James Audubon on one of Audubon’s fund-raising trips to Britain. Whatever the reason while still a teenager Lear decided to produce a book of drawings of parrots – and approached the newly opening London Zoo for permission to work in the aviary there. [Luckily, Lear was different to Audubon in that he drew from life, whereas the American although he often observed the birds in their natural habitat, had them killed before he drew them!]

When Lear was just 20, forty two of these parrot paintings were published in 1832 as Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae. This obviously came to attention of the President of the Zoological Society of London, Edward Stanley, 13th Earl of Derby who was himself an enthusiastic naturalist and collector. The earl financed natural history collecting expeditions, building up a network of agents all over the world to supply him with new species which were looked after by about 30 staff in an extensive menagerie and aviary at his estate at Knowsley Hall, near Liverpool.

The earl was keen to have a proper scientific record of his activities and interests and seeing the quality of Lear’s work invited the young man to Knowsley to record his collection. Lear was to spend much of the next 5 years working there intermittently and the result was the first volume of Gleanings from the Menagerie and Aviary at Knowsley Hall, with the text by John Edward Gray published in 1846.

It included creatures such as the “Eyebrowed Rollulus, The “Whiskered Yarke,” and the “Piping Guan.” While they are actually real and perfectly ordinary-looking creatures they almost sound as if they were names invented by Lear so maybe they were at least in part the inspiration for what was to come.

The great pity, from a horticultural or botanical point of view, is that Lord Derby did not ask him to record the Knowsley plant collection. Why is not clear because the earl was clearly interested in botany and gardening, actively collecting exotic plants, and maintaining a series of hothouses as well as fine gardens, and later the two men certainly corresponded about plants. The younger members of earl’s family may, however, be at least partly responsible for Lear’s nonsense work.

That’s because when Lear first arrived at Knowsley he was, unsurprisingly, treated as a middle-ranking member of staff, and ate with the servants. The story goes that the Stanley children kept making excuses to vanish from the dining table, and the earl discovered it was because of the funny man downstairs. Lear recalled Lord Derby coming to the top of the stairs which led down to the servants dining room and shouting “Mr Lear, Mr Lear, come up here!” From then on he dined as a guest.

Entertaining the earl’s grandchildren, must have honed his bizarre sense of humour and it led to him publishing A Book of Nonsense in 1846 [the same year as Gleanings] when he was 33 and dedicating it to his patron’s ‘great-grandchildren, grand-nephews and grand-nieces’.

Sadly, however, there was a downside to the intense observation required for his natural history paintings: his eyesight deteriorated badly and he was forced to switch his artistic focus to something less straining on his eyes. The earl helped him by subsidising a trip to Italy that helped Lear establish a new reputation as a landscape painter, and he was to spend most of the rest of his life abroad, painting and writing particularly in the Mediterranean and the Levant, as well as visiting India. However, animals and botanically recognisable plants often featured in his later landscapes and give a sense of accuracy to works that were otherwise primarily topographical in nature.

Whenever Lear did return to England he was always welcomed at Knowsley by the family, and after the earl’s death his son, who was Prime Minister 3 times, carried on acting as Lear’s patron, and then in turn his grandson, the 15th earl, for many years the Foreign Secretary, who he had entertained as a child in the nursery, also commissioned work.

Nonsense definitely took second place to serious landscape painting and it was another 25 years before he published Nonsense Songs, Stories, Botany and Alphabets in 1871, and followed it up with More Nonsense Pictures, Rhymes, Botany, etc, the following year 1872 and finally Laughable Lyrics. A Fourth Book of Nonsense Poems, Songs, Botany, Music etc in 1876. They were then assembled in a posthumous collection published in 1888.

Nonsense definitely took second place to serious landscape painting and it was another 25 years before he published Nonsense Songs, Stories, Botany and Alphabets in 1871, and followed it up with More Nonsense Pictures, Rhymes, Botany, etc, the following year 1872 and finally Laughable Lyrics. A Fourth Book of Nonsense Poems, Songs, Botany, Music etc in 1876. They were then assembled in a posthumous collection published in 1888.

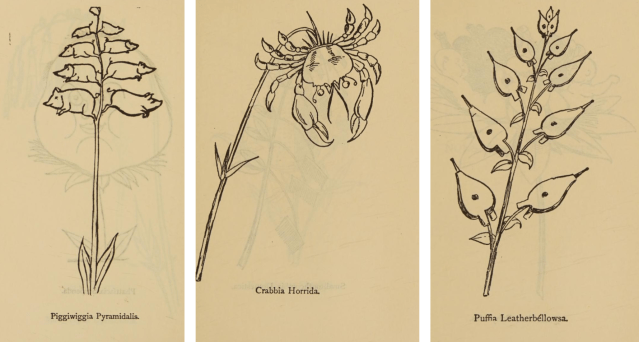

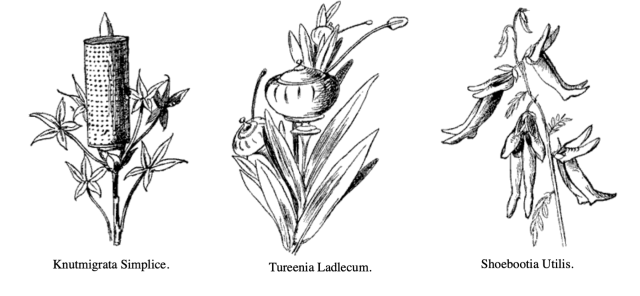

‘Nonsense Botany’ appeared in small groups in each of the three later volumes, but collectively they’ve been described by naturalist Richard Mabey as “a series of impish cartoons of preposterous floral inventions”. He’s right of course, but while they were preposterous almost beyond belief they are based on Lear’s sound and extensive knowledge of not only plants but their taxonomy or classification.

Categorisation and classification of the world and its contents had become a central tenet of science during the Enlightenment and remained at heart of Victorian science too. It was well understood by Lear who had been made an associate member of the Linnaean Society since 1831 when he was only just 20. He is known to have been an attentive reader of Charles Darwin and at one point he worked as an artist for John Gould, the natural-history entrepreneur who had actually worked on the famous finches that Darwin had studied and brought back from the Galápagos Islands. Gould included plates by Lear, usually without acknowledgement, in several of his major natural history books.

So when you think about some of Lear’s mad-cap creations they should be seen in the light of the emerging theory of evolution with its dead-ends and an understanding the way that chance and oddity worked in nature. The now globally accepted binomial nomenclature system devised by Linnaeus in the mid-18thc, gave plants [and later by extension other living creatures too] a two-part name in Latin: the first part identifying its genus, the second part identifying the particular species within that genus. The system offered Lear a golden opportunity to let his imagination run riot.

Naming things is very symbolic but in the nonsense world he had free range, and was able to choose pseudo-scientific names for its various inhabitants, blurring the line between the real world of scientific taxonomy, and his own invented world of visual and verbal fun.

Naming things is very symbolic but in the nonsense world he had free range, and was able to choose pseudo-scientific names for its various inhabitants, blurring the line between the real world of scientific taxonomy, and his own invented world of visual and verbal fun.

If you’d like to know more about the links between science and poetry especially nonsense then have a look at Daniel Brown’s The Poetry of Victorian Scientists: Style, Science and Nonsense which is freely available online and with a lot of references to Lear.

So finally let’s look at his Nonsense Botany for which he prefaces with an “Extract from the Nonsense Gazette, August, 1870” in a parody conjuring up the excitement of plant-hunting in wild places: “Our readers will be interested in the following communications from our valued and learned contributor, Professor BOSH, whose labours in the fields of Botanical Science are so well known to all the world. We are happy to be able, through Dr. Bosh’s kindness, to present our readers with illustrations of his discoveries. All the new Flowers are found in the Valley of Verrikwier, near the Lake of Oddgrow, and on the summit of the Hill Orfeltugg.”

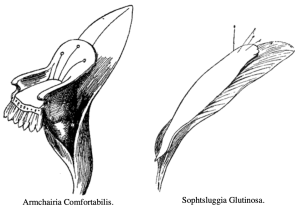

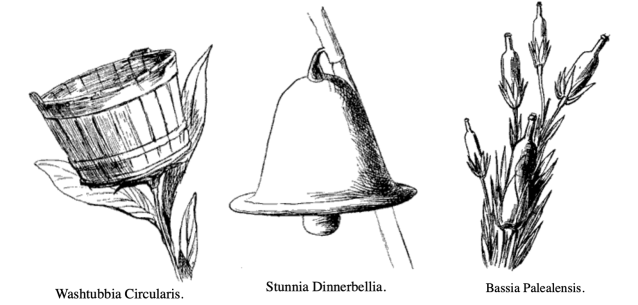

The Nonsense Botany sections had no text simply a series of drawings of everyday objects – such as a pipe, a bottle, forks, brushes, and kettles – that have been given mock-Latin names following the accepted Linnean binomial form and transformed into almost plausible looking plants, within almost recognisable plant forms.

The Nonsense Botany sections had no text simply a series of drawings of everyday objects – such as a pipe, a bottle, forks, brushes, and kettles – that have been given mock-Latin names following the accepted Linnean binomial form and transformed into almost plausible looking plants, within almost recognisable plant forms.

Doesn’t the pipe look like a delicate harebell? Perhaps the Manypeeplia could be in the bluebell family as could Jinglia and Bluebottleia?

Bubblia on the other hand is surely a species of muscari while Phatfacia is a rather bedraggled or deformed sunflower and Plumbunnia looks as if it’s related to strawberries?

Of course on anything other than cursory inspection they are bizarre but then many of the new plant discoveries being made in the late 19thc were pretty curious looking – just think about some of the weirdly shaped orchid flowers. Bottle, spoons and forks become an exotic looking daisy-like flower vaguely reminiscent of an echinacea, while an even stranger member of daisy family is suggested by the babies who make up Queeriflora.

Of course on anything other than cursory inspection they are bizarre but then many of the new plant discoveries being made in the late 19thc were pretty curious looking – just think about some of the weirdly shaped orchid flowers. Bottle, spoons and forks become an exotic looking daisy-like flower vaguely reminiscent of an echinacea, while an even stranger member of daisy family is suggested by the babies who make up Queeriflora.

Trying to identify which plants inspired Lear is, of course impossible, but after a while it can become quite addictive. Arthbroomia is surely in the thistle family.

But are Sophsluggia and Armchairia an anthurium, or maybe arums?

Stunnia is onviously a form of campanula but is Washtubbia related to Cobea, or Bastia paealensis to heather?

I’ve only seen a couple of attempts to identify possible links -the most convincing being the suggstion that Pollybirdia singularis has a lot of similarity to Erica cerinthoides.

I’ve only seen a couple of attempts to identify possible links -the most convincing being the suggstion that Pollybirdia singularis has a lot of similarity to Erica cerinthoides.

Among the others Cockatooka superba, shows a crested cockatoo emerging as a flower between two narcissus-like leaves, and seems based on his parrot drawings. But what to make of the rest? Personally I prefer the more complex drawings like the three below to the quick and simple outlines. Like Lear’s limericks, they’re not as funny to us as they were to his contemporaries. The writer G. K. Chesterton, for example knew them growing up and later wrote that Lear’s rhymes “constitute an entirely new discovery in literature, the discovery that incongruity itself may constitute a harmony,” and that if “Lewis Carroll is great in this lyric insanity, Mr. Edward Lear is, to our mind, even greater.” It’s interesting to note that they’ve been in print almost continually since his death in 1888 and they have inspired othersperhaps including James Thurber’s New Natural History.

Among the others Cockatooka superba, shows a crested cockatoo emerging as a flower between two narcissus-like leaves, and seems based on his parrot drawings. But what to make of the rest? Personally I prefer the more complex drawings like the three below to the quick and simple outlines. Like Lear’s limericks, they’re not as funny to us as they were to his contemporaries. The writer G. K. Chesterton, for example knew them growing up and later wrote that Lear’s rhymes “constitute an entirely new discovery in literature, the discovery that incongruity itself may constitute a harmony,” and that if “Lewis Carroll is great in this lyric insanity, Mr. Edward Lear is, to our mind, even greater.” It’s interesting to note that they’ve been in print almost continually since his death in 1888 and they have inspired othersperhaps including James Thurber’s New Natural History.

The sad thing is that despite his reputation as a nonsense writer Lear did remarkably little nonsense writing, and at the time there were at least some people who did not think he had written any of it, indeed that Edward Lear did not exist and was actually the nom-de-plume of Lord Derby instead. I’ll finish with Lear’s story about this told in the introduction to More Nonsense.

“I was on my way from London to Guildford, in railway carriage, containing, besides myself, one passenger, an elderly gentleman: presently, however, two ladies entered, accompanied by two little boys. These, who had just had a copy of the “Book of Nonsense” given them, were loud in their delight, and by degrees infected the whole party with their mirth. “How grateful,” said the old gentleman to the two ladies, “all children, and parents too, ought to be to the statesman who has given his time to composing that charming book!” (The ladies looked puzzled, as indeed was I, the author.)

” Do you not know who is the writer of it ?” asked the gentleman. ” The name is ‘Edward Lear,’ said one of the ladies. “Ah !” said the first speaker, “so it is printed; but that is only a whim of the real author, the Earl of Derby. ‘ Edward ‘ is his Christian name, and, as you may see, LEAR is only EARL transposed.” “But,” said the lady, doubtingly, ” here is a dedication to the great-grandchildren, grand-nephews, and grand-nieces of Edward, thirteenth Earl of Derby, by the author, Edward Lear.” “That,” replied the other, “is simply a piece of mystification; I am in a position to know that the whole book was composed and illustrated by Lord Derby himself. In fact, there is no such a person at all as Edward Lear.” ” Yet,” said the other lady, “some friends of mine tell me they know Mr. Lear.” “Quite a mistake! completely a mistake!” said the old gentleman, becoming rather angry at the contradiction; “I am well aware of what I am saying: I can inform you, no such a person as ‘ Edward Lear ‘ exists ! ”

Hitherto I had kept silence; but as my hat was, as well as my handkerchief and stick, largely marked inside with my name, and as I happened to have in my pocket several letters addressed to me, the temptation was too great to resist; so, flashing all these articles at once on my would-be extinguisher’s attention, I speedily reduced him to silence.”

Lear finally settled in San Remo where he died in 1888 but a plaque in his memeory was unveiled in Westmisnster Abbey on the centenary, to which I and a large group of children from my school were invited to attend, along with Vivian Noakes the leading expert on Lear who had been into school and enthused everyone about him.

Lear finally settled in San Remo where he died in 1888 but a plaque in his memeory was unveiled in Westmisnster Abbey on the centenary, to which I and a large group of children from my school were invited to attend, along with Vivian Noakes the leading expert on Lear who had been into school and enthused everyone about him.

Towards the end of his life the 15th earl invited him to “come over this spring and bring roomfuls of work with you. There is still space at Knowsley for a few more of your drawings, though I have a pretty good stock already.” Whether Lear’s mad botanical drawings were amongst them we don’t know but I hope they still make you laugh, as it made the children he drew them for laugh then….and next time you see an unusual plant, try to see it through Lears’ eyes and imagine what common object it might once have been!

Towards the end of his life the 15th earl invited him to “come over this spring and bring roomfuls of work with you. There is still space at Knowsley for a few more of your drawings, though I have a pretty good stock already.” Whether Lear’s mad botanical drawings were amongst them we don’t know but I hope they still make you laugh, as it made the children he drew them for laugh then….and next time you see an unusual plant, try to see it through Lears’ eyes and imagine what common object it might once have been!

For more information about Lear and his work, the recent biography by Jenny Uglow “Mr. Lear: A Life of Art and Nonsense” is a good place to start, but there are other biography by Peter Levi [1991] and Vivian Noakes Edward Lear, The Life of a Wanderer (1968), Edward Lear, 1812-1888 and The Painter Edward Lear (1991). She also edited many of his letters in Edward Lear: Selected Letters (1988). Other books of interest include Clemency Fisher’s A Passion for Natural History: The life and legacy of the 13th Earl of Derby (2002), Sarah Lodge’s. Inventing Edward Lear [2019] and Robert McCracken Peck’s (2021) The Natural History of Edward Lear

For more information about Lear and his work, the recent biography by Jenny Uglow “Mr. Lear: A Life of Art and Nonsense” is a good place to start, but there are other biography by Peter Levi [1991] and Vivian Noakes Edward Lear, The Life of a Wanderer (1968), Edward Lear, 1812-1888 and The Painter Edward Lear (1991). She also edited many of his letters in Edward Lear: Selected Letters (1988). Other books of interest include Clemency Fisher’s A Passion for Natural History: The life and legacy of the 13th Earl of Derby (2002), Sarah Lodge’s. Inventing Edward Lear [2019] and Robert McCracken Peck’s (2021) The Natural History of Edward Lear

from a letter by Edward Lear to Evelyn Baring, 1864

You must be logged in to post a comment.