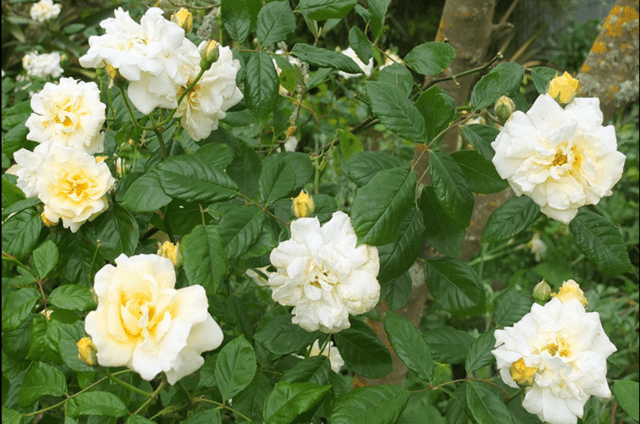

At one of our open garden days recently visitors were admiring a group of “Buff Beauty” roses which, despite the scorching heat and weeks of drought, still managed to show a few flowers, and were asking about their origins. I confess to not having known that much so went away to find out.

It turns out they along with several others in my garden including “Penelope” and “Cornelia” are Hybrid Musks, a group developed about a century ago by an Essex clergyman and his sister, and which, although they weren’t that popular then, have not only stood the test of time but become extremely popular and robust additions to the garden.

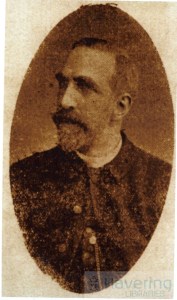

So today’s post is about that vicar, the Rev Jospeh Pemberton, his sister Florence, and their gardeners Jack and Ann Bentall who were later to carry on their work creating a complete new family of hardy roses.

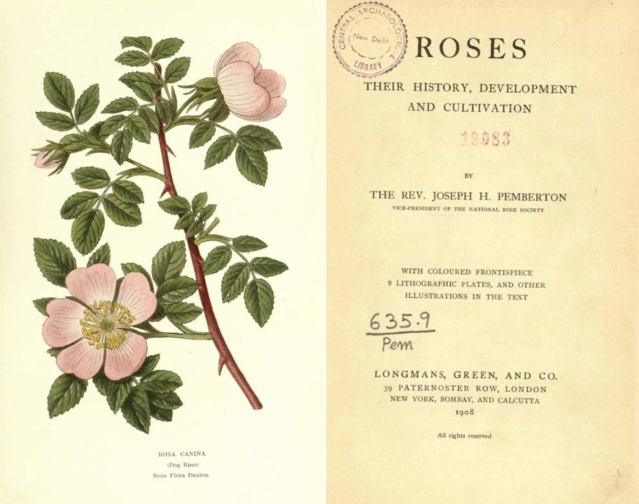

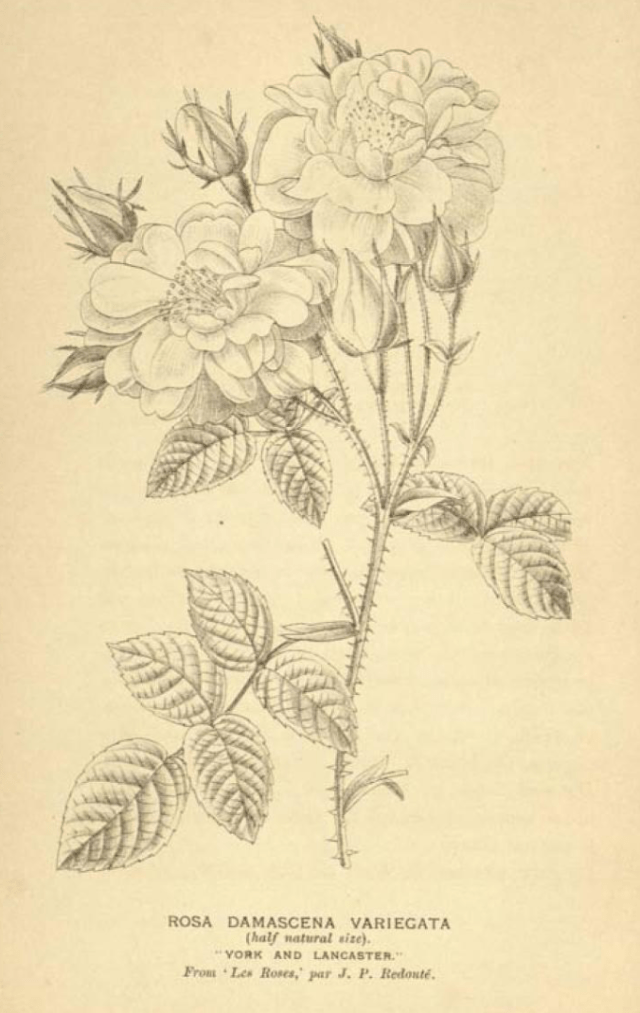

The quotes in the text, unless otherwise referenced, come from Joseph Pemberton’s Roses, their history, development and cultivation published in 1908. The images of roses are all of varieties introduced by Joseph, Florence or Ann Bentall.

Joseph Pemberton was born in 1852, and Florence five years later, into a well-to-do family who, in the early 1860s, settled at Havering-atte-Bower, Essex. The village was once the location of the Royal Palace of Havering used by the monarchy from pre-Norman Conquest until 1620. Their parents’ place wasn’t quite so grand but it was certainly unusual: The Round House, a villa designed in the 1790s by John Plaw for a London merchant William Sheldon. Oval in shape it is said by the London Encyclopaedia to have been modelled on a tea caddie although that’s been disputed. Whatever the reason it was the first building in the country to have this shape, and it was to be Joseph and Florence’s home for most of the rest of their lives.

Joseph and Florence’s father, also Joseph, was a great lover of roses, so the children grew up ” in a rose atmosphere, and loved the rose when a child in petticoats.” Joseph senior was particularly taken by standard roses, which he bought from Thomas Rivers, a nurseryman from Sawbridgeworth in Hertfordshire, and author of “ The Rose Amateur’s Guide“.

Joseph and Florence’s father, also Joseph, was a great lover of roses, so the children grew up ” in a rose atmosphere, and loved the rose when a child in petticoats.” Joseph senior was particularly taken by standard roses, which he bought from Thomas Rivers, a nurseryman from Sawbridgeworth in Hertfordshire, and author of “ The Rose Amateur’s Guide“.

I tried to track down the date when growing roses as standards was first tried, or at least became common but the Oxford English Dictionary doesn’t have any entries covering the term, and the earliest usage I can find on Biodiversity Heritage Library is in 1823 in Henry Philips Sylva florifera : the shrubbery historically and botanically treated when it’s clear they were already part of the garden scene. River’s contemporary, friend and fellow nurseryman William Paul implies in his book The Rose Garden [1848] that the idea originated in France, which was undoubtedly the leading rose breeding country, but gives no evidence while elsewhere other websites , equally without providing any evidence, suggest the technique originated in late 18thc Germany. If anyone knows more authoritative please get in touch.

Joseph soon “had a small garden of my own. There were three standards in it — red roses; I did my own pruning, but they hardly ever gave me a Sunday buttonhole; the situation was too shady, and there were laurels close by. When about twelve years of age my father showed me how to bud.” He might also have learned from watching or working with the family gardener who was “a kind old man [but] I never knew his name until when my grandmother died he was pensioned off; we just called him “gardener,” nothing more. He would bud red and white roses on the same standard,”

St James Hall, Piccadilly where the first national rose show was held from Illustrated London News, 3rd April 1858

Joseph senior attended rose shows. The first of these was held in London in 1858 organised by Thomas Rivers, William Paul and Samuel Reynolds Hole and proved highly successful. They became a regular event at Crystal Palace and elsewhere and the young Joseph was sometimes taken along . However his father never exhibited but this didn’t stop Joseph thinking about it himself and he later recalled that in 1874, following his father’s death, “I ventured on my first attempt. I went round the standards the day before the show and found we could just get twelve varieties.”

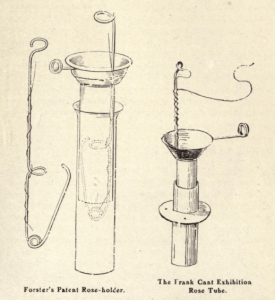

“Assisted by the gardener we borrowed a chrysanthemum stand with legs and tubes; we covered the board with lycopodium [a kind of moss] on which the roses rested, cut with foot-stalks only, no foliage; the man said that was the proper way to do it, but having been to the Crystal Palace, I had my doubts. Although we had only the twelve roses and did not take any extra blooms, yet the stand won second prize. That did it; from henceforth I was on the warpath; fifty standards were ordered from Rivers, and a piece of the kitchen garden was prepared where they could grow all by themselves.”

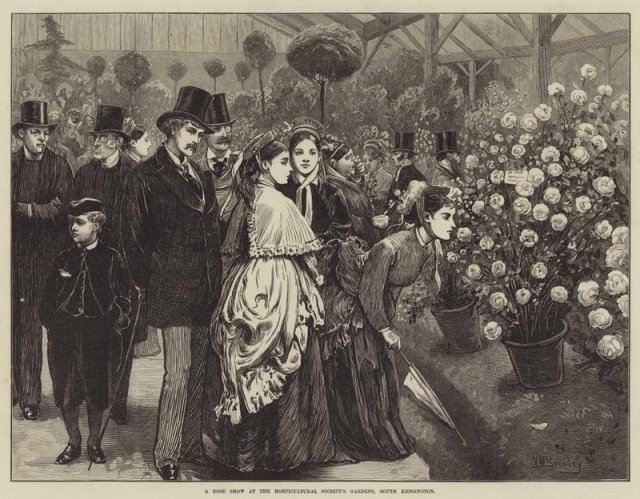

A Rose Show at the Horticultural Society’s Gardens, South Kensington, from Illustrated London News 12th July 1873

“The next year I went to two local shows, and in 1876 to the Alexandra Palace and Crystal Palace exhibitions, where Mr. Benjamin R. Cant and Mr. George Prince took me in hand, giving me advice in staging and kindly encouragement.” It was in December that same year that the National Rose Society was formed and the following year, along with his sister Florence, Joseph signed up for membership. It was a real turning point in his life and he remained closely involved with the society until his death in 1926. [See this earlier post for more information about the founding of the NRS]

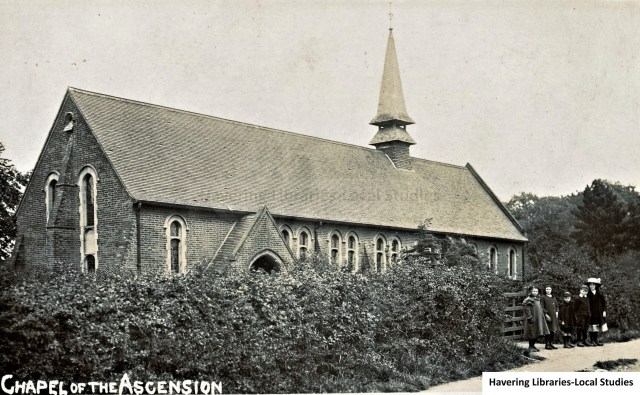

Meanwhile he was also training as a priest and was ordained in 1881. Aged 29 he became curate of Saint Edward The Confessor at Havering and given particular care of Collier Row a small settlement in Hainault Forest, becoming priest in charge of the new Church of the Ascension in the village when it was opened in 1886. He was to remain there for 43 years until his retirement in 1923.

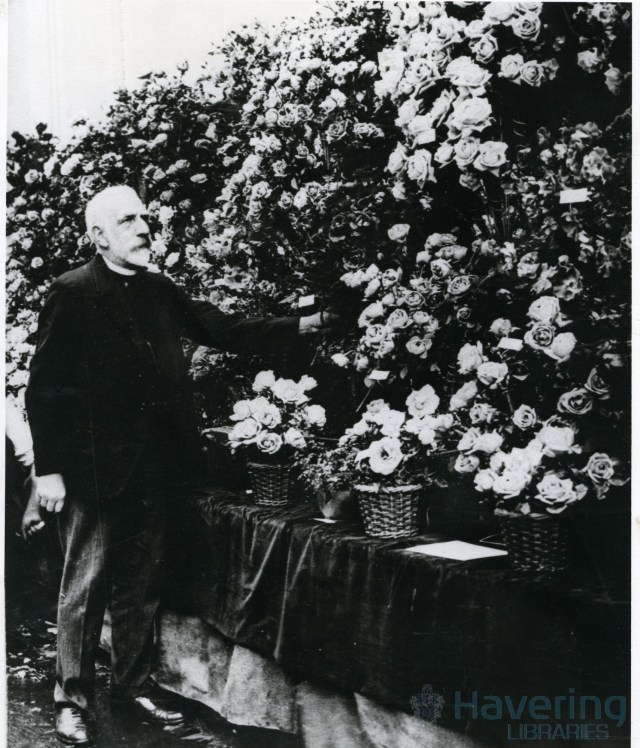

Alongside his ministry he remained fascinated by roses, and working closely with Florence continued exhibiting and competing in rose shows. He was a regular top prize winner as can be seen from reports in the gardening press. For example in the Journal of Horticulture’s report of the July 1886 National Rose show his name crops up 7 times across different classes. Interesting these reports usually list the names of the winning roses and I’d estimate about half the names were of French varieties.

What surprised me – and also must have surprised Joseph – is that in its early days the National Rose Society was mainly concerned with “modern” roses and had little interest in the “old fashioned” varieties. “We did not in those days trouble about names; we gave them names of our own, such as “Aunt Helen’s Rose … Grandmother’s Rose… Aunt Betsy’s Rose,” When shows were held “they, like Cinderella, were left at home.”

Maidens Blush, Aimee Vibert and Rosa Mudi

However, “One year, I forget which, when the National Rose Society held its exhibition at South Kensington, round the corridors that ran into the conservatory then adjoining the Albert Hall, [This was presumably the RHS Garden –see this earlier post for more information] I took up a box of Cinderellas — Maiden’s Blush, Aimee Vibert, Red Provence, and Lucida were some of them — and staged them, not for competition, labelled ” Grandmother’s Roses.” That box attracted considerable attention; folks discovered old and forgotten favourites, and I have been told the demand for them and impetus given to raise the modern decorative roses is owing in part to that exhibit.”

From then on Joseph and Florence were partners at rose shows with great success, travelling all over the country and winning the high honours for their “old fashioned” roses. Their vintage year was 1896 – starting in Colchester on 18 June and ending in Leicester on 4 August. They entered 12 shows, staging 49 boxes of roses and winning 48 prizes including 32 firsts. Once it got going the National Rose Society began holding three shows a year, including one in London, and when Joseph retired from the ministry in 1923 he claimed that he had exhibited at every one of those London shows since the first in 1877.

You’d think that being a clergyman in a growing parish as well as growing and exhibiting roses would be enough to keep anyone busy but, like several other well-known rosarian clerics, Joseph clearly had more energy than most and in 1908 he published his book Roses : Their history, development and cultivation aimed at rose-loving amateurs noting that “fashion has changed” and although “in the latter half of the nineteenth century the rose was regarded primarily as an exhibitor’s flower, and books on its cultivation, although useful to all growers, were written chiefly from an exhibitor’s point of view. … the rose is now extensively grown for garden and house decoration, for which no flower is more adaptable or more popular.” The book was illustrated mainly in black and white by Florence and a second edition appeared in 1920.

You’d think that being a clergyman in a growing parish as well as growing and exhibiting roses would be enough to keep anyone busy but, like several other well-known rosarian clerics, Joseph clearly had more energy than most and in 1908 he published his book Roses : Their history, development and cultivation aimed at rose-loving amateurs noting that “fashion has changed” and although “in the latter half of the nineteenth century the rose was regarded primarily as an exhibitor’s flower, and books on its cultivation, although useful to all growers, were written chiefly from an exhibitor’s point of view. … the rose is now extensively grown for garden and house decoration, for which no flower is more adaptable or more popular.” The book was illustrated mainly in black and white by Florence and a second edition appeared in 1920.

Joseph also became even more involved with the National Rose Society and in 1906 was made vice-president before, in 1909, being awarded the first medal named in honour of Samual Reynolds Hole for his work with them and for his book. Just a couple of years later in 1911 he was made president of the society and was then a vice-president for the remaining 15 years of his life. Surely enough for anyone. But no!

In 1913, in partnership with Florence, he found time to set up a nursery to grow the roses he loved most, his “Grandmother’s roses”. The nursery flourished and so with the help of John and Ann Bentall his gardener and his gardener’s wife he then decided to go one stage further.

“Of all the departments of rose growing, none are more fascinating than that of raising roses from seed, and it ought to be one of the pursuits of all true rosarians who can give their time to it. However much we may enjoy the excitement of winning the chief prizes at the leading rose shows of the year, it may be the result of our own cultural skill, but it is won with other people’s roses. Whereas the production of a new rose to which is awarded a gold medal is not only a joy to the raiser, but he becomes a benefactor to the whole rose world.”

How closely the Bentalls were involved can be judged from two surviving replies from Joseph to John’s letters sent from France during the Great War. These are available to read in full but Joseph recounts all sorts of details of about numbers of roses budded, seedlings being trialled, and how he and Ann Bentall were the only people to do all the work.

As his book shows he was well aware of the hybridising and cross-breeding efforts of nurserymen like Paul and Rivers as well as several amateur rosarians. However, he felt that for some rose types the end of the road in improvements had probably arrived. For example, “the Hybrid Perpetual has apparently reached its ultimate; there may be more to come, but at any rate there are other directions in which the raiser can and is proceeding. As an instance, we can point to the new race of Hybrid Sweet-briers, for which the rose world is indebted to the cultural skill of the late Lord Penzance.” [For more on Penzance and his rose-breeding see this earlier post]

Joseph and Florence’s aim was simple: to create a new strain of the scented roses of their childhood which would repeat flower for many more months rather than generally blooming once and finishing by July. Scent too was clearly an important factor and Jospeh was to write about its importance in an article for the Journal of the International Garden Club in 1918.

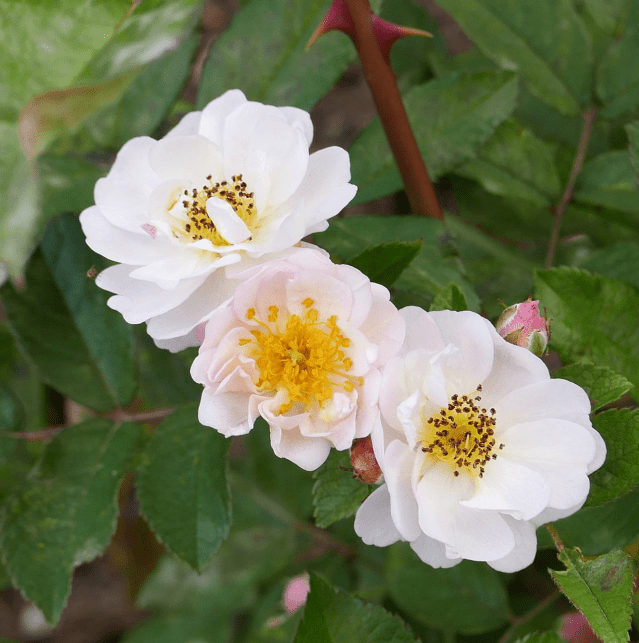

They began working with a rose named “Trier” a seedling by the German rosarian Peter Lambert 1889-1939, which had only been introduced in 1904. Not all of its the “ancestors” are known, so its origins remain a bit obscure. but they included both Rosa multiflora, and Rosa moschata (the musk rose). ‘Trier’ shared some of the qualities possessed by the ‘old’ roses Pemberton admired, including good scent and large trusses of semi-double flowers.Crucially, it was repeat flowering. All qualities that the Pembertons wanted, along with disease resistance and a strong growing habit, so it was used as a parent with several different hybrid tea or polyantha roses.

There would have been thousands of seedlings raised before they produced what they considered successful cultivars and went to exhibit them at a rose show. However when they did so they got a bit of a shock. The Pembertons considered their new roses to be hybrid tea roses, despite their differences with the more typical roses in that category, particularly the fact that they were cluster-flowered. The judges disagreed and ruled them out, suggesting instead that as they smelled similar to musk roses, perhaps they should be called hybrid musks and hybrid musks they have remained ever since.

Eight new varieties, with mainly shrub-like characteristics were picked out when they published their first catalogue Pemberton’s Select Rose List, soon after the nursery opened. These were “Daphne”, “Danae”, “Moonlight”, “Ceres”, “Galatea”, “Clytemnestra”, “Queen Alexandra” and “Pemberton’s White Rambler”. They had very little in common with each other, apart from their scent, and the fact they were raised by the same team. But they formed the basic breeding stock for further cross-breeding.

In their 1913 catalogue they say how much they “appreciate a visit from the lovers of roses, whether purchasers or not . .. it is a pleasure to have a talk …” It went on to explain that “the roses offered in this list, are dwarf or bush plants, and have been grown and cultivated by the Reverend JH Pemberton and Miss Florence Pemberton, primarily for their own enjoyment. Friends, however, have desired plants, so the roses are now offered to the general public.” By the 1916 season there were 160 cultivars on the list, with eventually some 35–40,000 rose bushes being grown annually at the nursery for sale. Many of these varieties have now vanished from cultivation of course but there are several which are still in commercial production, including all those illustrated.

Theoretically Pemberton’s Hybrid Musks were developed too late to qualify as “old” garden roses, but since their habits and care are similar they are often informally classed together with them. Their offspring, as a group, are probably still unbeaten in the shrub border, and even David Austin still offers many of them alongside his own introductions. Pemberton also bred a number of conventional hybrid teas, and several Multiflora ramblers which are still worth growing.

By the time Joseph died in 1926 the nursery had expanded with additional ground in nearby Stapleford Abbots looked after by another of his gardeners, a Mr Spruzen. I suspect this was Henry Spruzen who according to the 1911 census was a “domestic gardener” from Theydon Bois. Joseph bequeathed the rose fields to his gardeners, those near the Round House to the Bentalls and those at Stapleford Abbots to Spruzen. However Florence wanted to stay involved and perhaps to reward the gardeners financially she bought the fields back, and then on her own death in 1929 gifted them back again.

The breeding programme continued, with the new roses introduced between 1926 and 1929 being the responsibility of Florence. One of these was a cherry-red rose named “Robin Hood” in 1927 mainly known because it was one of the parents of the famous floribunda rose “Iceberg” introduced in 1958. After the Bentalls took over the nursery was renamed Brokenback Roses and it was Ann Bentall, a skilled propagator, who seems to have taken over the breeding programme, supported by her husband John [usually known as Jack] , and later their son, another Jack.

She is responsible for introducing many of the more well-known new varieties including “Buff Beauty'”, “Fortuna” and “The Fairy” as well as “Ballerina” [although that may not strictly be a musk hybrid – such is the difficulty of working out genetics and taxonomy!] She was the recipient of a National Rose Society Gold Medal for her work.

It is thought that the younger Jack Bentall continued with the rose business until around the 1970’s, when he retired. After changing hands and then being largely abandoned the nursery site was taken over in 2018 by a charity, Jack’s Place which uses gardening as therapy for lonely, socially isolated and socially excluded people.

Other rosarians have also carried on crossing and producing new hybrid Musk varieties, particularly Kordes in Germany, Lens in Belgium and other breeders in the USA, and they have also been used as parents for some of the crosses bred by David Austin.

Unfortunately many of the earliest introductions have disappeared probably without trace, although there is a search out for them, and a substantial but still incomplete collection has been built up at The Hall in Havering-atte-Bower, the neighbouring property to The Round House and once home to the Pembertons’ cousins. It has been since 1978 the home of St Francis Hospice and visits to see the gardens are possible by arrangement.

For more information the best place to start is undoubtedly the website associated with the hospice which has several pages dedicated to Pemberton roses and their history. Other good places to look are the post about Pemberton’s hybrid Musks by my fellow blogger Planting Diaries , the website of Dutton Hall, holder of the National Collection, and if you have access to back copies of the RHS journal The Garden Michael Gilson’s article from way back in July 1995.

You must be logged in to post a comment.