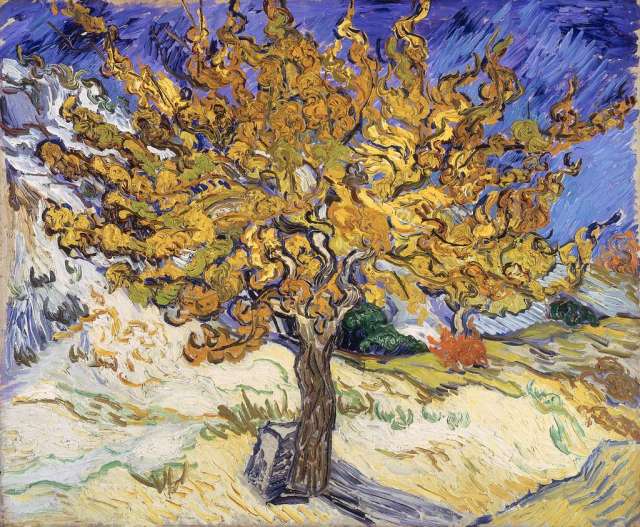

It was here we go round the mulberry bush in my garden recently – or rather here we go under the mulberry tree. Mine is a Black Mulberry grown almost as much for its foliage and shape, as for its squishy sharp-flavoured dark red fruit which grow hidden from obvious sight beneath the leaves. Since its branches reach down to the ground collecting it involves a lot of clambering about [and often a few curses] trying to avoid tripping over . But the effort is usually worth it.

I also have a White Mulberry whose fruit don’t hide away under the foliage, but since they are virtually tasteless the ease of picking does’t come into it because I don’t bother. However the leaves would be really useful if I wanted to keep Bombyx mori, because they are the preferred food of their caterpillars, better known as silkworms.

Both sorts have long histories in the garden and that’s what today’s post is going to explore BUT what’s it got to do with the famous nursery rhyme, the murder of St Thomas à Becket and the late Queen Elizabeth?

Morus alba

For most of the world there are two main sorts of mulberry – the black [Morus nigra] and white [Morus alba] – although in North America there is a third major sort – the red mulberry [Morus rubra]. I’m going to generally use those Latin names rather than Black, White and Red for the rest of the post. Unfortunately taxonomy is never that simple so if you want to know more taxonomic detail read the next paragraph – if not skip over it!

First of all no-one seems even to have been able to produce a definitive list of Morus species. Kew’s Plant List first published in 2013 had 217 plant names associated with Morus , although many were different names for the same species and it suggested that maybe there are as few as 17 distinct species. The updated version renamed World Flora Online, lists 303 but again mostly synonyms whilst the World Food and Agriculture Organisation reckons there are as many 68 species but hundreds – if not thousands – of cultivars – worldwide. Almost all the cultivars are of Morus alba and almost none of Morus nigra because genetic analysis has discovered that M.nigra has far more chromosomes than any other species of flowering plant: a total of 308 in 22 duplicate sets, which pretty well prevents mutations or sports arising. More recently, however, a 2015 study thought there might really only be 8 separate species. If you want to pursue this further take a look at: “Definition of Eight Mulberry Species in the Genus Morus by Internal Transcribed Spacer-Based Phylogeny”, by Qiwei Zeng et al but unless you’re a botanist prepare to be baffled!

Black Mulberries probably come from the area around modern-day Iran but because they are culturally undemanding, and can be propagated easily by layering, seed or cuttings they are now naturalised widely from the Balkans to China. They have big heart-shaped leaves and branches that droop elegantly down to the ground, often to the point of looking like they need to be propped up. Because of that they can develop wonderfully gnarled and contorted shapes as they age, and often within just a couple of decades they have what Sarah Raven called a “been there forever” look.

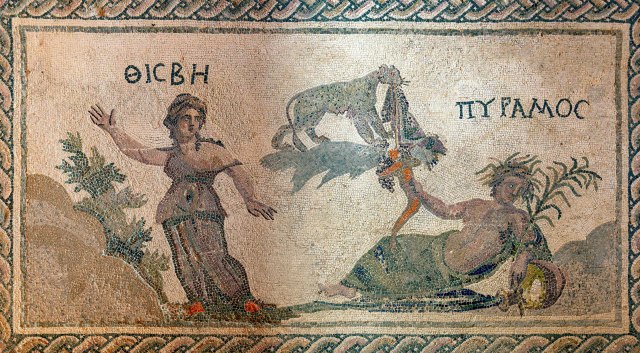

Unfortunately their delicious fruit does not store well so it has never really entered commercial production and you’re very unlikely to ever see it on the shelves in Tesco or even Waitrose. It’s also impossible to pick without getting your hands stained and looking like you’ve committed a bloody crime. The Roman poet Ovid offered an explanation of why this was the case in his telling of the story of the ill-fated lovers Pyramus and Thisbe which I’m sure you’ll also know from Shakespeare’s version in A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

The pair arranged to meet”beneath the shadow of a tall mulberry tree,

covered with snow-white fruit, close by a spring”

Thisbe sees a lion who is devouring its kill and runs away, dropping her scarf. The lion seizes it and in doing so stains it with the blood of his meal. When Pyramus arrives he sees the bloody scarf and thinking Thisbe has been eaten falls on his sword, his blood spurting everywhere and…

“By that dark tide the berries on the tree

assumed a deeper tint, for as the roots

soaked up the blood the pendent mulberries were dyed a purple tint.”

The Romans introduced Black Mulberries right across their empire, and traces of them have been found at several sites in Britain. Since trees are long lived and easy to propagate it’s no surprise they are often recorded in monastery gardens. They were certainly common enough in the mediaeval period to give their name to a colour – either ‘mulberry’ or ‘murrey’.

White Mulberries come from further east in Asia. It was probably introduced, along with sericulture – silk production – via the Silk Road in the early medieval period. M.alba is usually a more upright tree than M.nigra and its fruit, despite being insipid, is easy to pick, and dries and stores well so is used as a mild sweetener in cooking and in Chinese medicine. Incidentally, despite their name M.alba doesn’t always have pale fruit, and instead it’s much more common for them to be the same shades of red and purple as other mulberry species.

As the home of M. alba China had long had a monopoly of silk production but in 751 an Islamic army defeated the Chinese in Central Asia, and amongst their many prisoners were skilled silk weavers who were then taken back to start a silk industry across the Arab empire.

Despite the oft-recounted story that silkworms will only eat white mulberry leaves and won’t touch those of black mulberries, in fact they will, and they did for a long time because M.nigra was widespread while M.alba probably hadn’t arrived from China by the time the European silk industry took off. The big differences between the two are that the M.alba coppices more readily, is more resilient to regular harvesting of its leaves and produces better quality silk.

By the 12thc sericulture was flourishing in Byzantium and mainland Greece, while the following century saw it reach Tuscany. By the 14thc Southern Spain had just two major crops:olives and mulberries, and had become a big exporter of silk, France following suit in the 16thc and soon taking over from Spain as the major producer. Initially all were feeding their caterpillars with the leaves of M.nigra as M.alba was still rare, but gradually in the warmer climates of the Mediterranean region it took over.

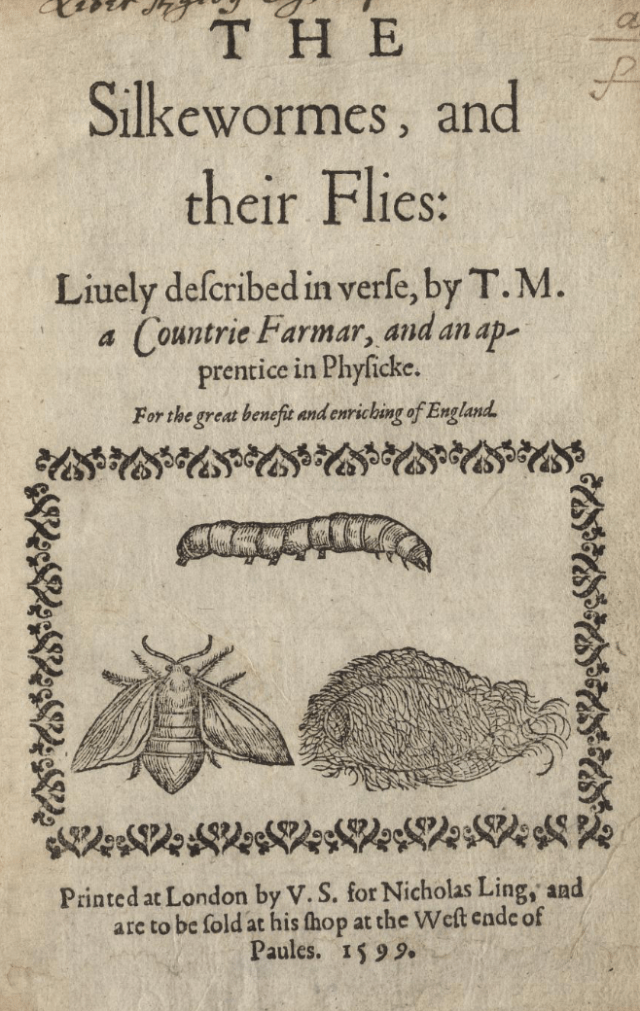

At the end of 16thc Henri IV, the King of France, oversaw big expansion of the French industry and some 10,000 trees were planted in the Tuileries Gardens in Paris and in the grounds of royal castles near the capital. His efforts were supported by the great agricultural writer and reformer Olivier de Serres who published La Cueillette de la soye, literally The Gathering of silk, in 1599. In Britain in the same year Thomas Moffett, the Father of Entomology [and supposedly Little Miss Muffett], published a 75 page long poem [yes that’s 75 pages not lines] called The silk wormes and their Flies which also drew on the story of Pyramus and Thisbe and went on to describe the silk worms he had seen on a visit to Tuscany and making a plea to his countrymen to start a silk industry at home “that shall enrich yourselves and children more Than ere it did Naples or Spain before.”

At the end of 16thc Henri IV, the King of France, oversaw big expansion of the French industry and some 10,000 trees were planted in the Tuileries Gardens in Paris and in the grounds of royal castles near the capital. His efforts were supported by the great agricultural writer and reformer Olivier de Serres who published La Cueillette de la soye, literally The Gathering of silk, in 1599. In Britain in the same year Thomas Moffett, the Father of Entomology [and supposedly Little Miss Muffett], published a 75 page long poem [yes that’s 75 pages not lines] called The silk wormes and their Flies which also drew on the story of Pyramus and Thisbe and went on to describe the silk worms he had seen on a visit to Tuscany and making a plea to his countrymen to start a silk industry at home “that shall enrich yourselves and children more Than ere it did Naples or Spain before.”

It was also all part of the rise of consumerism, especially in luxury goods like silk, which was noticeable across all parts of elite society in the late 16th and early 17th centuries which I don’t have time to go into but if you want to know more take a look at Linda Levy Peck’s wonderful account of the phenomenon Consuming Splendor. [2005]

It was also all part of the rise of consumerism, especially in luxury goods like silk, which was noticeable across all parts of elite society in the late 16th and early 17th centuries which I don’t have time to go into but if you want to know more take a look at Linda Levy Peck’s wonderful account of the phenomenon Consuming Splendor. [2005]

The call was taken up by James I when he came to the throne in 1603. Plans were afoot by 1606 for the granting of a patent to import as many as a million white mulberry trees at about a penny apiece, “the patentee to bring in only the white mulberry; plants of themselves and not slips of others: and of one year’s growth at least”

In 1607 de Serre’s book was translated by Nicholas Geffe as The Perfect Use of Silk-wormes and their Benefit, in which he argued “we may as well be silk masters as sheep masters,” and suggested planting mulberry trees everywhere, in preparation for feeding silkworms. The book was dedicated to James who saw establishing sericulture as a hugely ambitious project, with national honour at stake.

The king led the way and the papers of Robert Cecil, his chief minister, record that “Francis de Verton, alias Forest, of London, gent, has undertaken to bring into this kingdom not only a great number of silk worms but great store of mulberry trees for the maintenance of the worms, whereby an exceeding great benefit will redound as well to all sorts of labouring people as to others. Warrant authorising him to bring in free of custom as many mulberry trees as to him shall seem good for five years, all other persons being forbidden to bring in the same.”

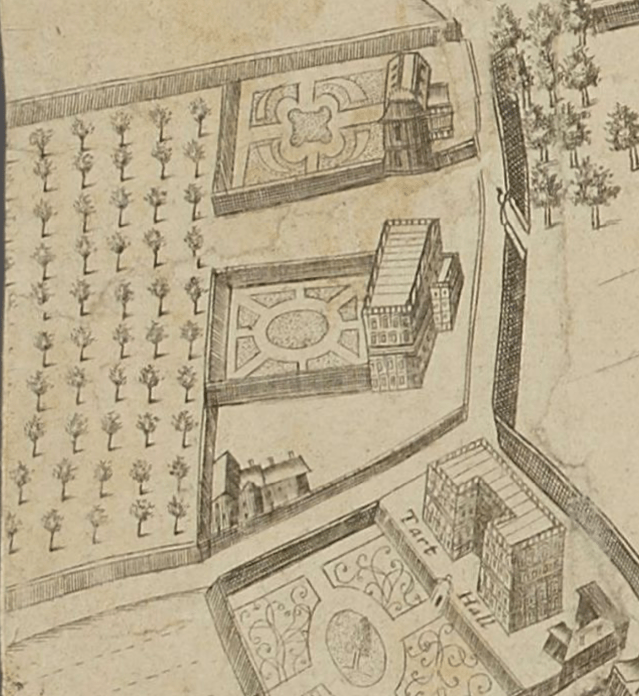

This meant tens of thousands of White Mulberry saplings were imported from Languedoc, while lots of Black mulberries were also planted. The king also wrote to the deputy lieutenant of each county telling them to instruct all major landowners “to purchase and plant mulberry trees at the rate of six shillings per thousand”. In 1609 £935 was spent by “embanking a piece of ground and for planting of mulberry trees” on a 4 acre site near where Buckingham Palace stands. A house was also built for its keeper, William Stallenge, an MP, senior customs official and “fixer” for Robert Cecil. Given that no-one had any experience of silkworm rearing Stallenge was also commissioned to oversee the publication of Instructions for the Increasing of Mulberrie Trees the same year.

Mulberries were also planted at all the other royal palaces including Greenwich and Oatlands, both of which belonged to James’s wife, Anne of Denmark. Charlton House, the finest surviving Jacobean mansion in London, and once home to the tutor of Henry Prince of Wales, believes that the mulberry in its garden was another of those first royal plantings.

As only Black Mulberry trees have survived from this period, it is often wrongly assumed that James made a mistake by planting them instead of the White. The records suggest both were planted but White had only been introduced to Britain in the 1590s and simply did not cope well with cold and wet conditions and so failed to thrive. A series of heavy frosts and late springs would also have meant that the hatching of silkworm eggs could not be synchronised with the first flush of tender leaves, and the silkworms themselves also failed to thrive well despite every effort. Since the White Mulberry trees don’t have the interesting structure of the black mulberry and the fruit isn’t up to much perhaps they were simply grubbed out when the attempts to raise silkworms were abandoned, while Black Mulberry trees were preserved.

Nevertheless James didn’t give up on the idea and in 1622 sent a letter to the Virginia Company instructing them to establish a silk industry in the warmer climes of the new colony where they had access to the native Red Mulberry. Like the British project, after some initial success the Virginia scheme failed too, although attempts continued to well into the 18thc.

For more info about the American experiment see Unravelled Dreams: Silk and the Atlantic World, 1500–1840 by Ben Marsh (2020)

By 1632 “the custody and keeping of the Mulberry Garden near St James’s, in the county of Middlesex, and of the mulberries and silkworms there, and of all the houses and buildings to the same garden belonging” had passed to Lord Goring who built another house nearby which was often mentioned in contemporary diaries and later, after several more transformations, was to become Buckingham Palace.

After the silk experiment petered out the Mulberry Garden became the site one of London’s early commercial pleasure grounds. In May 1654, John Evelyn said it was “now ye only place of refreshment about ye towne for persons of ye best quality to be exceedingly cheated at.” Later, the restored Charles II was once found “in a horrid debauch in the mulberry-garden, drinking to filthy excess till 3 o’clock in the morning.” It was definitely a fashionable place to be seen, and as such became a a setting in some Restoration comedies. Sir Charles Sedley wrote The Mulberry Garden, set there while others like Wycherley’s Love in a Wood are partly set there. However Goring House was destroyed by fire in 1674, and it’s thought the Mulberry Garden, was closed as a place of entertainment, about the same time.

After the silk experiment petered out the Mulberry Garden became the site one of London’s early commercial pleasure grounds. In May 1654, John Evelyn said it was “now ye only place of refreshment about ye towne for persons of ye best quality to be exceedingly cheated at.” Later, the restored Charles II was once found “in a horrid debauch in the mulberry-garden, drinking to filthy excess till 3 o’clock in the morning.” It was definitely a fashionable place to be seen, and as such became a a setting in some Restoration comedies. Sir Charles Sedley wrote The Mulberry Garden, set there while others like Wycherley’s Love in a Wood are partly set there. However Goring House was destroyed by fire in 1674, and it’s thought the Mulberry Garden, was closed as a place of entertainment, about the same time.

Black Mulberries continued to be planted right across the country for their fruit, but there were still attempts to get a silk industry off the ground. John Evelyn in later editions of Sylva says “It is demonstrable, that mulberries in four or five years may be made to spread all over this land; and when the indigent, and young daughters in proud families are as willing to gain three or four shillings a day for gathering silk, and busying themselves in this sweet and easie employment, as some do to get four pence a day for hard work at hemp, flax, and wooll.” In 1718 a patent was issued to the Raw Silk Company to produce silk on 40 acres in Chelsea. About 2,000 mulberries were planted and a large house with heating was built ‘for nursing silkworms’. Although enough was produced to make a dress for the Princess of Wales the business collapsed when the import tax on raw silk was removed. The trees were sold and presumably cut down. There’s a lot more about this enterprise in an article on Morus Londinium

Yet another attempt was made as late as 1930 at Lullingstone Castle in Kent by Lady Hart Dyke. This produced enough material for wedding dresses and coronation robes for the Queen and Queen Mother, but it too failed and the 20-acre plantation of white mulberries was later grubbed up. For more information see the Lullingstone website. which has some wonderful Pathe News video clips.

With its royal association, it should be no surprise that the National Collection of Mulberries was established by the late Queen Elizabeth and held at Buckingham Palace. Mark Lane, the gardens manager there spent several years searching out trees, initially from British nurseries then adding species native to America, the Middle and Far East and Europe. I’ve seen varying estimates of how extensive the collection is but I think it contains at least 35 kinds, divided into 9 species and subspecies and includes 24 cultivars. There are others planted at Kensington Palace and Marlborough House.

But, after all that history, you’re obviously desperate to know what’s the connection to the nursery rhyme? I suspect the answer is not much and certainly nothing definitive! One possible interpretation is that it refers to the failure of the silk industry because white mulberries are too sensitive to thrive “on a cold and frosty morning”. I think that’s probably retro-fitting it to history since the rhyme isn’t recorded anywhere until 1849 and then only as a more rhythmic variation to here “we go round the bramble bush.” However. in French the word mûre, means both mulberry and blackberry, while Peter Coles, the author of the standard work on Mulberries notes that the Old English word ‘morbeam’ also refers to both, so there’s definitely room for confusion!

The other main theory is that there was a mulberry tree in the grounds of Wakefield Prison and women prisoners danced and exercised around it. This has been researched by Robert Duncan, former governor of the prison who wrote an account of his findings in Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush: House of Correction 1595 – HMP Wakefield 1995. Unfortunately it doesn’t seem to be available either on-line or second-hand, so I can’t say much more about his evidence. Certainly the prison seems to thinks its true as it even figures on their coat-of-arms. Nominated for the Woodlands Trust Tree of the year award in 2016 the original had to be felled in 2017 because it became dangerous but it has been replaced with another grown from its own cuttings. For more on the various myths associated with the rhyme see this video from The Resurrectionists

The other main theory is that there was a mulberry tree in the grounds of Wakefield Prison and women prisoners danced and exercised around it. This has been researched by Robert Duncan, former governor of the prison who wrote an account of his findings in Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush: House of Correction 1595 – HMP Wakefield 1995. Unfortunately it doesn’t seem to be available either on-line or second-hand, so I can’t say much more about his evidence. Certainly the prison seems to thinks its true as it even figures on their coat-of-arms. Nominated for the Woodlands Trust Tree of the year award in 2016 the original had to be felled in 2017 because it became dangerous but it has been replaced with another grown from its own cuttings. For more on the various myths associated with the rhyme see this video from The Resurrectionists

After publishing this post I was surprised and pleased to get a message from a regular reader telling me about yet another, and probably more plausible story behind the rhyme. After Henry II famous plea to deal with Thomas A Becket – ‘Who will deliver me from this turbulent priest?’ – four knights went to Canterbury and leaving their horses and surcoats by a mulberry tree just a few yards from the cathedral cloisters and went in search of the archbishop.

As a recent Archdeacon of Canterbury noted they “then proceeded to murder him in a very unpleasant way. I won’t go into details, but they would have got quite messy in the process. They then returned to their horses by the mulberry tree in the courtyard of the cellarer’s hall to make their getaway. But first they had to clean themselves up, and to wash some of the dirt of the murder off their swords and hands….Hence the familiar nursery rhyme, ‘Here we go round the mulberry bush.’ … ‘This is the way we wash our hands… (of the blood)’, ‘This is the way we clean our teeth (or our swords)’, ‘this is the way we put on our clothes (or our cloaks)’, ‘…on a cold and frosty morning.’

For mulberry lovers, Londoners in particular, there is a fascinating website Morus Londinium, which aims to document all the capital’s mulberry trees, especially the older ones, and invites everyone to help uncover and record them. Once you start looking you’ll find it hard to stop!

For more information: There is an interesting and well researched history of all three main mulberry types on the website of the International Dendrological Association:

For more information: There is an interesting and well researched history of all three main mulberry types on the website of the International Dendrological Association:

You must be logged in to post a comment.