Which is the oldest public park in Britain? Most books and websites will tell you that the first funded from the public purse was Birkenhead Park which opened in 1845. Others claim that the honour goes to Derby Arboretum opened in 1840, although that was funded by a private benefactor. However there’s a strong case to be made for somewhere that was laid out well over 200 years earlier at Moorfields.

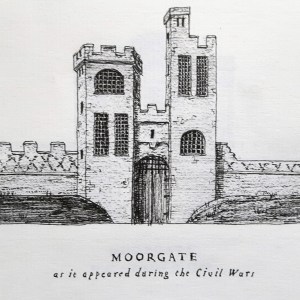

Say Moorfields to anyone in London and they’ll probably think of the country’s leading eye hospital or maybe confuse it with Moorgate, the nearby busy tube station. In fact both the station and hospital were built on parts of a series of planned public walks just outside the capital’s Roman walls and only a few minutes walk north from Guildhall, the centre of the City of London’s civic life.

Between 1606 and 1618 the three fields that made up The Moor were laid out as “princely” public walks as a symbol of civic power and pride, following the latest European fashion. However, things didn’t always go according to plan and these days all that’s left are two small open spaces: the sadly shabby “modernist” mess of Finsbury Square and the more sedate tree-filled green sanctuary of Finsbury Circus.

Apologies there aren’t as many images as usual, because there are no really early views of Moorfields, and even the few maps are not particularly detailed.

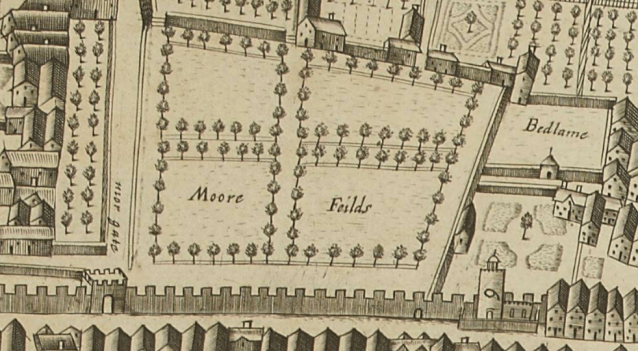

As you can see from the Braun & Hogenberg map at the top of this post although most of Tudor London was densely built up within the city walls, it was beginning to expand into the surrounding countryside. However the fields to the north were boggy and ill drained, difficult to cross on foot and so unusable for building or even farming. Nevertheless they were long recognised as valuable because the streams that flowed through them were vital parts of the city’s waste disposal system with their water flowing into the ditch that ran round the city walls washing the rubbish thrown into it down to the Thames. This was important enough to be recognised by the city authorities who fined tenants who blocked the flow of water, and reduced the rents of those who “well and honestly safeguard the Moor and keep the said water-course clean” .

The fields had another longstanding use: recreation. The first historian of London, the monk writing in the 1170s recorded that the fields were well used especially in winter: “When the great marsh that laps up against the northern walls of the city is frozen, large numbers of the younger crowd go there to play about on the ice. Some, after building up speed with a run, facing sideways and their feet placed apart, slide along for a long distance.”

The fields had another longstanding use: recreation. The first historian of London, the monk writing in the 1170s recorded that the fields were well used especially in winter: “When the great marsh that laps up against the northern walls of the city is frozen, large numbers of the younger crowd go there to play about on the ice. Some, after building up speed with a run, facing sideways and their feet placed apart, slide along for a long distance.”

“Others are more skilled at frolicking on the ice: they equip each of their feet with an animal’s shin-bone, attaching it to the underside of their footwear; using hand-held poles reinforced with metal tips, which they periodically thrust against the ice, they propel themselves along as swiftly as a bird in flight or a bolt shot from a crossbow.”

Then, as early as in 1415, the civic authorities themselves caused parts of the Moor to be laid out in gardens for renting –which must be the earliest example of allotments known. A new postern gateway – Moorgate – was cut through the wall to allow easier pedestrian access.

A large-scale drainage scheme in the early 16th century transformed it from watery meadows to the more domesticated semi-suburban landscape shown on the Copperplate Map of the mid-1550s. [see below]

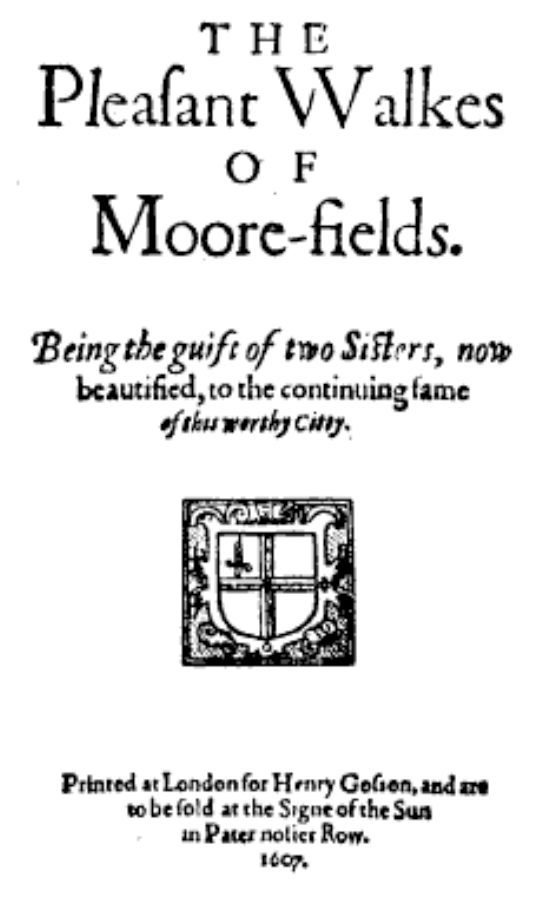

Nevertheless Moorfields had been, according to Richard Johnson author of The Pleasant Walkes of Moore-fields [1607] still considered “a most noisome and offensive place, being a general laystall, a rotten morish grounde whereof it first tooke the name. This field was for many years was environed and crossed with deepe stinking ditches and noisome common sewers, and was of former times ever held impossible to be reformed…..And likewise the two other fields adjoining, which until late time were infectious and very grievous unto the city, and all passengers, who by all meanes endeavoured to shun these fields, being loathsome both to sighte and scent.”

So what happened?

We know in precise detail because The City of London was largely governed by the Court of Aldermen, one representing each of its 26 wards. They kept careful minutes of their proceedings, known as the Repertories, which luckily survive in their entirety in London Archives.

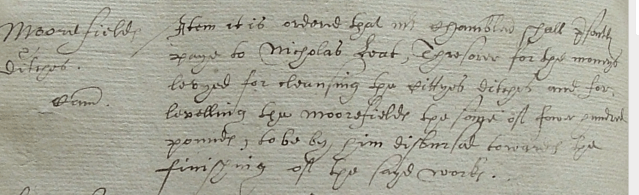

Repertories of the Court of Aldermen 17th January 1605-6 Rep 27 f.142 [my photo]

One of the City’s Aldermen

scanned from my copy of Hugh Alley A Caveatt for the Citty of London, 1598

The first mention of a project to develop Moorfield came in January 1606 when “It is ordered that Sir Thomas Bennett, Sir Henry Rowe, Sir Thomas Campbell and Sir Wm Romney knights shall confer with Percival a gardener touching the keeping and ordering of Moorfields” A couple of months later they agreed to pay John Perceval and his colleague Michael Wilson £5 a year each and an extra shilling every day “they shall work to level the two Moorfields vis Little Moore Fields and Great Moore fields and to plant the same with such trees as they shall be directed by order of this court.” Percival and Wilson were both founding members of the Worshipful Company of Gardeners which was chartered on the 18th September 1605 just a few months earlier with a royal charter that gave the new company theoretical control over all the “arts and mysteries” of gardening within 12 miles of the city.

Repertories of the Court of Aldermen, 9 Oct 1606 Rep 27 f.284v [my photo]

The money to pay for this work – £400 in the first instance – was handled by Nicholas Leate, an immensely wealthy merchant in the overseas trade, three times master of the Ironmongers Company and a member of the city’s Common Council. He was also, in his spare time, a plant collector, and friend of both John Gerrard and John Parkinson giving both of them plants he had imported via his trading connections.

Leate deserves his own post one day but in the meantime if you want to know more I’ve written about him for the London Gardener, the annual ,journal of the London Gardens Trust.

Leate seems to have been the driving force behind the idea, and persuaded his wealthy connections that creating public walks at Moorfields would be good for the city’s image and the health of its citizens.

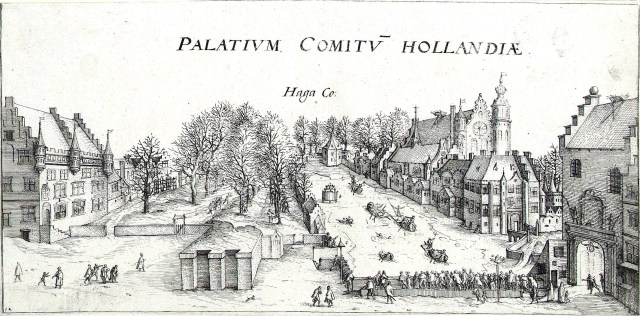

Where had he got the idea from? Apart from one trip to Normandy he is not known to have travelled to Europe where public walks were just becoming a new urban feature – Antwerp, Paris, Lucca and The Hague all seem to have created them in the previous decade or two.

The answer may have been closer to home. Francis Bacon had masterminded the creation of walks in the grounds of Grays Inn in the 1580s, having travelled widely in France as young man. The City was mindful of its reputation and there was sense of rivalry and wanting to keep up with the legal Jones. As a result Johnson tells us that “the new and pleasant walkes were planned & greatly furthered, by Sir Leonard Holliday, in the time of his Mairalty and through the great paynes and industry of Master Nicholas Leate.”

However the City Fathers were hard-headed business men and it was not to be done with public money. Instead they backed a system of ” benevolences”: an appeal to the wealthy to donate for a good cause with Leate acting as treasurer. Unfortunately it appears that the money raised wasn’t sufficient and after several failed attempts at more arm-twisting of richer citizens, in the end the city authorities reluctantly had to cough up £200 or half the costs.

However the City Fathers were hard-headed business men and it was not to be done with public money. Instead they backed a system of ” benevolences”: an appeal to the wealthy to donate for a good cause with Leate acting as treasurer. Unfortunately it appears that the money raised wasn’t sufficient and after several failed attempts at more arm-twisting of richer citizens, in the end the city authorities reluctantly had to cough up £200 or half the costs.

from Faithorne & Newcourt’s Exact Delineation, surveyed 1640s but not published until 1658

There were three fields that had the name Moorfields: unexcitedly called Lower, Middle and Upper Moorfields. Work started on the Lower Fields, the one immediately outside the walls. Levelling and building a wall around part of them before laying out the walks took a year although there were constant worries about money and, even at this early stage, not everyone was happy with the idea, with one tenant of the land refusing to demolish a shed he had there. The Court of Aldermen was peremptory: demolish it yourself or we will do it for you because.the shed “doth hinder the finishing of the brick wall which is now in hand for the beautifying and inclosing of the said fields.” It’s an interesting comment because beauty is not a word one necessarily associates with city magnates at this time. Eventually in June 1607 payment was made “for 107 Elmes sett in the said fields” in the shape of a St George’s Cross “at 20d a peece.”

As a result Lower Moorfields become an ornamental rather than a practical space. This is generally lauded as a far sighted piece of public policy: effectively creating the first public park. Certainly that is how the walks are seen in most garden history texts and when reading between the lines, in official sources of the time.

As a result Lower Moorfields become an ornamental rather than a practical space. This is generally lauded as a far sighted piece of public policy: effectively creating the first public park. Certainly that is how the walks are seen in most garden history texts and when reading between the lines, in official sources of the time.  They have been as Johnson claimed “reduced from the former vile condition, unto most faire, and royall walkes as they now are” but perhaps the contemporary public response to these changes should encourage us to see the development in another light and ask what the revellers, sportsmen and servants shown in the Copperplate map actually thought?

They have been as Johnson claimed “reduced from the former vile condition, unto most faire, and royall walkes as they now are” but perhaps the contemporary public response to these changes should encourage us to see the development in another light and ask what the revellers, sportsmen and servants shown in the Copperplate map actually thought?  Like the poor in more recent times castigated for keeping coal in their baths, traditional users did not seem to appreciate what they had been offered.

Like the poor in more recent times castigated for keeping coal in their baths, traditional users did not seem to appreciate what they had been offered.

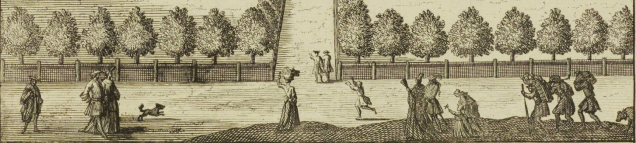

The new gravel paths may have been tree lined, but they were also lined with massive oak rails which stopped easy access to the grass areas inside. Furthermore, the northern and eastern edges had high brick walls built around them to stop traffic, both pedestrian and carts, entering and crossing the walks. Soon after their opening, what the Corporation found was that their splendid walks were not used in the way that had been intended or expected. Instead the trees were used to hang washing lines, whilst the rails were broken down to allow access to the grass, or served as counters for hawkers and peddlers. Less than 3 years after work started and just after the completion of work on the Lower Field, ‘keepers’ had to be employed ‘to stop people From spoyling and annoying the Moorfields and the trees there growing’. Aldermen also had to introduce stringent byelaws against all forms of selling, as well as laundry and rubbish dumping.

The new gravel paths may have been tree lined, but they were also lined with massive oak rails which stopped easy access to the grass areas inside. Furthermore, the northern and eastern edges had high brick walls built around them to stop traffic, both pedestrian and carts, entering and crossing the walks. Soon after their opening, what the Corporation found was that their splendid walks were not used in the way that had been intended or expected. Instead the trees were used to hang washing lines, whilst the rails were broken down to allow access to the grass, or served as counters for hawkers and peddlers. Less than 3 years after work started and just after the completion of work on the Lower Field, ‘keepers’ had to be employed ‘to stop people From spoyling and annoying the Moorfields and the trees there growing’. Aldermen also had to introduce stringent byelaws against all forms of selling, as well as laundry and rubbish dumping.

Of course to be effective rules require enforcement so in early 1609 Percival and Wilson were appointed official “keepers” of the fields. They were to “watch ward and attend the said fields continually excepting a reasonable time to take their dinner and repast and also sometimes in the night as occasion may serve”. They were, at their own expense, to keep the ditches and drains free, clear up the rubbish that was left including “soil” (ie sewage), keep the beggars out, stop people doing their laundry, drying their clothes, as well as maintain the paths, trees and rails etc (although they could claim the cost of materials ) and generally keep things “pleasant and orderly” all for the sum of £15 a year each.

Of course to be effective rules require enforcement so in early 1609 Percival and Wilson were appointed official “keepers” of the fields. They were to “watch ward and attend the said fields continually excepting a reasonable time to take their dinner and repast and also sometimes in the night as occasion may serve”. They were, at their own expense, to keep the ditches and drains free, clear up the rubbish that was left including “soil” (ie sewage), keep the beggars out, stop people doing their laundry, drying their clothes, as well as maintain the paths, trees and rails etc (although they could claim the cost of materials ) and generally keep things “pleasant and orderly” all for the sum of £15 a year each.

Middle Moorfields from Faithorne & Newcourt’s Exact Delineation, surveyed 1640s but not published until 1658

Another round of arm-twisting now started in 1612 to raise money for work on the Middle Field. The road needed diverting, the brick wall extending and the tenter fields used by the clothworkers to clean and dry their wool needed relocating. After that the trees were planted, this time in the shape of a St Andrew’s Cross in honour of the Scots origins of James I. Most of this work, which cost well over £250, also ended up being paid for by public funds. All of this must have been exhausting for everyone involved so it wasn’t until 1615 that serious consideration is given to laying out the Upper Field and it wasn’t until 3 years later in 1618 that the final walks are completed, twelve years after the first mention.

Upper Moorfields, from Faithorne & Newcourt’s Exact Delineation, surveyed 1640s but not published until 1658

It was clearly a not universally popular makeover, and in effect hijacked the fields from what had been their previously accepted principal purpose. It wasn’t that ordinary people couldn’t go there, it was simply they weren’t supposed to use the fields as they had been wont to do. The problems that arose when the first field was converted did not go away.  The by-laws were constantly reissued suggesting they were ineffective. Ordinary Londoners wanted space to launder and dry their clothes, they wanted food sellers, stalls and traders. They even wanted to attended theatrical shows, listen to quacks or mountebanks. The authorities had different priorities! So what happened?

The by-laws were constantly reissued suggesting they were ineffective. Ordinary Londoners wanted space to launder and dry their clothes, they wanted food sellers, stalls and traders. They even wanted to attended theatrical shows, listen to quacks or mountebanks. The authorities had different priorities! So what happened?

Generally the locals got their way albeit at a cost. Two keepers even if they were “on duty” all the time couldn’t permanently patrol such a large area [nowadays it stretches from London Wall to Old Street] and it was clearly not in their financial interest to do so. Instead they turned a blind eye to contraventions of the by-laws, and collected backhanders.

Generally the locals got their way albeit at a cost. Two keepers even if they were “on duty” all the time couldn’t permanently patrol such a large area [nowadays it stretches from London Wall to Old Street] and it was clearly not in their financial interest to do so. Instead they turned a blind eye to contraventions of the by-laws, and collected backhanders.

During the course of the next century and a half there is a constant almost palpable feeling of tension in the records, not just between the City fathers and the local users of the fields but also between the aesthetic aims of the city and its hard-nosed economic ones. This can be clearly seen in attitudes to encroachments, as many houses round the field knocked holes in the wall to provide themselves with direct access and when challenged knew exactly the price they would have to pay to buy the rights from the authorities. At the same time tolls were charged by illicit barrier keepers, allowing carts and horses to take short cuts.

During the course of the next century and a half there is a constant almost palpable feeling of tension in the records, not just between the City fathers and the local users of the fields but also between the aesthetic aims of the city and its hard-nosed economic ones. This can be clearly seen in attitudes to encroachments, as many houses round the field knocked holes in the wall to provide themselves with direct access and when challenged knew exactly the price they would have to pay to buy the rights from the authorities. At the same time tolls were charged by illicit barrier keepers, allowing carts and horses to take short cuts.

But worse, much worse, was to come as we’ll see next week…

detail from a print of Old Bethlehem Hospital ad Moorfields c.1700

You must be logged in to post a comment.