Last week’s post ended on a gloomy note and said worse was to come. And there couldn’t have been much worse than the Great Fire of London of 1666 which burnt 80% of the old walled city. In the aftermath Moorfields was quickly overrun. People set up shelters and tents, then wooden sheds and then shops until one of the walks became known as New Cheapside and was paved over. The rails and trees were used as firewood and there was even debate about whether to allow brick-makers to dig for clay “to incourage the more free and plentifull supply of Bricks for rebuilding”. It was nearly ten years before Moorfields were clear again and replanting and repair could begin.

After that although there was constant renewal of the walks it was against a background of threats of development and neglect, before, at the end of the 18thc, the builders eventually won the battle and most of Moorfields disappeared.

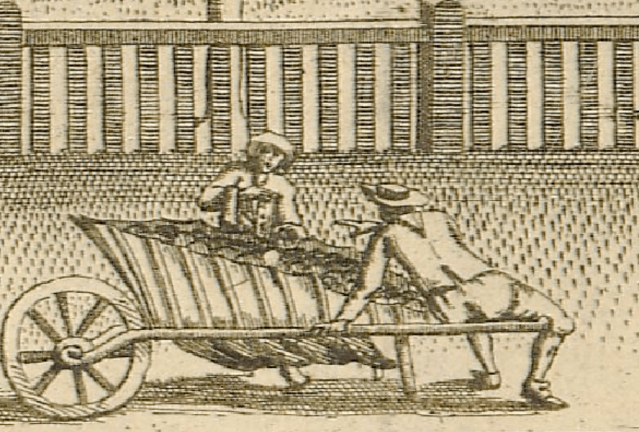

The booksellers of Moorfields using the rails of the walks as their counter, detail from an undated early 18th century print, private collection

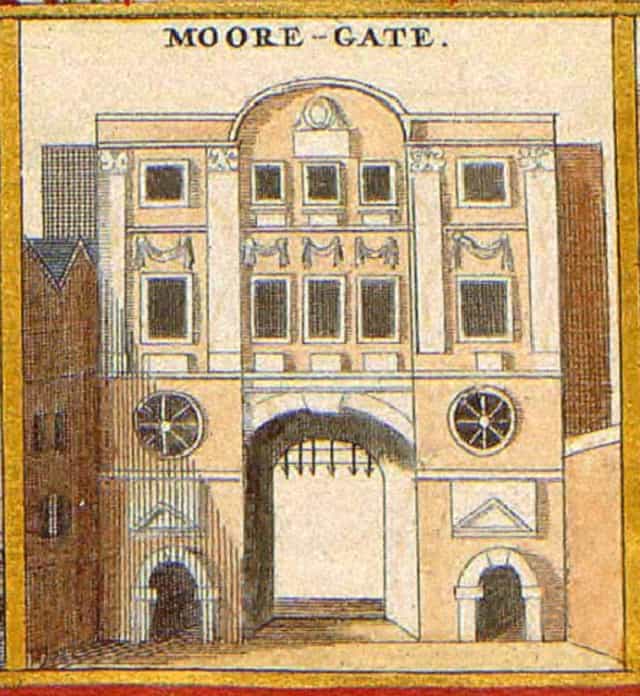

By the time of the Great Fire the fields had already become distinctly urbanised. The surrounding formerly semi-rural and suburban areas were built up much more densely and in 1672 Moor Gate itself was rebuilt on a bigger scale making access to and from the walks much easier. That encouraged the builders.

Just a few yards on the other side of the city wall was Little Moorfields, the last large undeveloped site near the city and the authorities, always on the lookout for income, decided to lease it for development to raise cash.

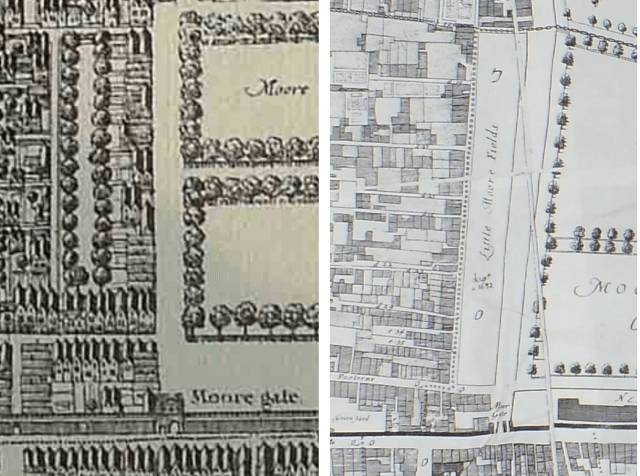

Little Moorfields from the Leake & Hollar post-Fire map 1667 and the Ogilby & Morgan map of rebuilt London, 1676

The local residents had other ideas. They were “much annoyed and damnified by reasons of the great quantity of rubbish lying in and the ruinous condicon of the sd field …and a great many nuisances comitted and … that there are several new buildings erected without leave.” No matter. In 1678 the city went ahead and granted a building lease. Now the fireworks really started. The Merchant Taylors Company owned property nearby and complained on a combination of economic and what we would see as environmental grounds.

detail from an undated early 18th century print, private collection

Their houses “now fronting the said fields have enjoyed that light Aire and prospect they now enjoy beyond the memory of Man” and development would inevitably lower their rents. That might have been self-interest but they also argued presciently that if Little Moorfields was built on “there will not want designing men in time to propose the takeing the Quarters [ie the three sets of walks] to build to bring a revenue to the Chamber” Others argued along the same lines.

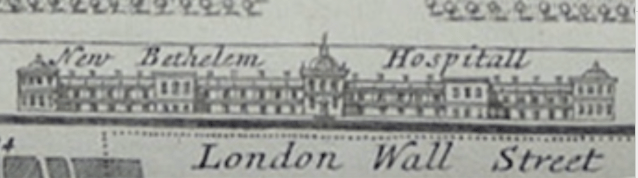

detail from an undated early 18th century print of Moorfields and Bethlem Hospital, private collection

It was all to no avail and in 1682 the City invited bids for building. Work even started clearing trees and digging foundations but legal battles continued and the case went to court in 1684. The Crown intervened against development, the Attorney-General saying the land had been given by the Crown “for continual enjoyment” and not for building “which was a perversion of the ancient uses of the ground.” The City dug its heels in, arguing they “are not to be directed what use they shall make of their own ground.” The dispute ground on for years and so it wasn’t until 1692 that the lease of Little Moorfields was finally sold and development went ahead. Who says planning delays are a modern phenomenon?

Even though the houses have long gone the site of Little Moorfields is still discernible on maps as the block in which Moorgate station stands.

detail from an undated early 18th century print of Moorfields and Bethlem Hospital, private collection

To be fair to the City they were still intent on repairing and maintaining the main parts of the walks. The late 1670s and then the 1680s saw the replanting of the trees, the reconstruction of the paths and rails and the return to the routine maintenance programme. Named gardeners were contracted to do the work, separated now entirely from the post of keeper, although it was still the keepers who supervise and carry out the instructions of the Court of Aldermen. However while the keepers were originally paid, by the end of the century the reverse was true, and would-be keepers had to pay for the privilege. By 1710 the keepership was bought for £129 and by the late 18th century it was was worth £200, proving beyond doubt that the tolls, fees and bribes must have been substantial to make it worthwhile spending so much on buying the office..

The battle over the development of Little Moorfields was just the first skirmish. In the 1680s a new lunatic asylum was wanted to replace the old Bedlam or Bethlehem Hospital. Robert Hooke was given the site – a section of the long thin city ditch just outside Moorgate, but it was decided that would not be impressive enough, so to give the new building a much needed grander setting a slice of the walks of Lower Moorfields was taken over and laid out slightly differently.

The new hospital was to become another of the attractions of the fields, alongside money lenders on what became known as Usurers walk, preachers, prostitutes, quacks, gay cruisers on Sodomites Walk, prize-fighters, and hucksters of all sorts. It also became a site for crime as can be seen via Old Bailey On-line .

detail from an undated early 18th century print of Moorfields and Bethlem Hospital, private collection

The 18th century continued the pattern of a continuous round of repairs, replanting matched by encroachment and nuisance. The surrounding wall and gateways were constantly being eaten away by residents – in 1720, for example, an arch in the wall with the city’s arms was taken down to allow easier access and the arms used to decorate a neighbouring house, while elsewhere 58ft of wall had been demolished and replaced by 3 shops opening onto the fields!

By 1729 the corporation asked for rubbish to be laid in the depressions in the field caused by constant illicit crossing by carts – to fill them back up!

Afterwards everything was rerailed and regravelled again –with the City also ordering that “iron stumps be affixed on the severall gates leading into Moorfield to prevent the sd gates from being lifted off and carried away.” Three years later replanting was considered. London’s nursery trade had improved beyond all recognition from the 1660s when the trees for the lime avenues at Hampton Court had to be imported from Holland because no local nursery could provide them. Now when the aldermen asked for suggestions for the replanting scheme three were recorded in great detail, with the contract being given to Mr Adam Holt who “proposed to plant 231 english elms none less than 8′ girth and 15′ high, 20 ft distant from each other at 16d each and to dig and plant them, also make good whatever dies within 2 yrs from the planting for 30s a year.”

From John Rocque’s Map of London, 1747

Development continued apace and in 1751 when St Luke’s hospital was built on the northern edge the walks were completely surrounded, and after 1754 Moorfields virtually disappears from the Court of Aldermen’s records. I have not yet been able to locate the arguments relating to the final phase of the walks existence but I suspect the city authorities were simply worn down by the constant battle to maintain them. They were also desperately trying to encourage people back to the City proper to revitalise it and [as always] provide some much needed revenue. They encouraged redevelopment schemes , preferably on classical lines anywhere that they could be fitted in.

This suited George Dance, the City of London’s surveyor and architect, who had succeeded his father in that role in 1768 at the age of only 27.

In 1777 Dance proposed replacing the walks on Upper and Middle Moorfields with Finsbury Square, west-end style classical terraces around a central garden on Upper Moorfields and some associated terraced streets running across the rest of Middle Moorfield.

When it was completed all that was then left were the remains of Lower Moorfields in front of Bedlam.

Detail from William Faden’s 1813 update of Richard Horwood’s 1799 map of London which captures the demolition of Robert Hooke’s Bedlam Hospital midway. Image scanned from copy of The A-Z of Regency London

These survived until the hospital was moved to Lambeth and Hooke’s building demolished. Dance then laid out another grand residential development around the oval centrepiece of Finsbury Circus. The gardens were laid out in 1815-17 to his designs by the City Surveyor William Montague and were Initially run by a committee of leaseholders of the surrounding houses.

While both schemes started out as housing aimed at getting people to move back to London it wasn’t that long before they began to be converted or demolished and rebuilt as offices and other commercial premises, a process which continued ever since. Now none of the original buildings, or even their original replacements survive in Finsbury Square, and it also suffered badly during World War II before being further damaged by the building of an underground carpark, which was finally completed in the early 1960s. [See this earlier post for more on that]. Since then there have been several redevelopments schemes proposed but as you can see from the clips from Google Maps show, the site is still, to put it politely, a mess.

There is a much fuller description of the site on the Inventory of the London Gardens Trust.

Finsbury Circus has had a slightly better fate despite having a tunnel cut through it [and later covered over] for the underground railway in 1864. But by the end of the century its residential nature had also given way to commercial interests. As a result in 1898 it was recommended that an Act of Parliament be obtained to ensure that the gardens were kept as public open space, and in 1900 the central garden was acquired by the City Corporation for public use.

The proposed pavilion

Railway construction caused more damage over a ten year period during the construction of Crossrail between 2010 and 2020 and this was followed by a major restoration project beginning in 2023 although the planned pavilion was dropped from the scheme this summer because of rising costs.

So these two small spaces are all that’s left of Britain’s oldest park, and although the City which runs Finsbury Circus is proud of the fact that that it is the oldest park in the City and the last remains of Moorfields dating from 1607, sadly Islington Council has almost zero information about Finsbury Square  and if you check Moorfields out on the London Gardens Trust inventory what you get is … [that’s obviously not a criticism of the inventory which covers all the surviving parks and green spaces of the capital really really well ] but it proves the point that maybe it’s time for Moorfields to get its history and importance acknowledged more widely!

and if you check Moorfields out on the London Gardens Trust inventory what you get is … [that’s obviously not a criticism of the inventory which covers all the surviving parks and green spaces of the capital really really well ] but it proves the point that maybe it’s time for Moorfields to get its history and importance acknowledged more widely!

You must be logged in to post a comment.