Montreal is home to one of the great botanic gardens of the world. You might be forgiven for thinking that since Canada was once part of the British Empire that the garden was one of the wide network linked or founded by Kew in the 19th century. But it wasn’t.

Montreal is home to one of the great botanic gardens of the world. You might be forgiven for thinking that since Canada was once part of the British Empire that the garden was one of the wide network linked or founded by Kew in the 19th century. But it wasn’t.

Instead, like the gardens at Niagara I wrote about last week, it was only set up in 1931 in part as response to unemployment caused by the Great Depression. Its great protagonist was a Catholic monk, enthusiastic botanist, and Quebec nationalist, Brother Marie-Victorin.

He was a charismatic and persuasive figure and after a long campaign convinced the authorities that laying out a new botanic garden would not only be a good way of providing employment but also bring in tourists and of course be good for encouraging research and interest in plants and botany.

As usual the images are mine unless otherwise acknowledged. Also apologies that some of the links to archival images haven’t “stuck” as they should have done but they can all be found on the garden’s archive website

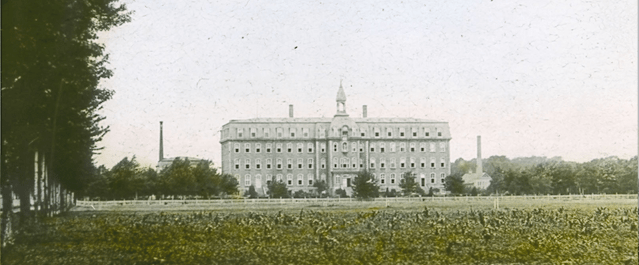

Plans for a botanic garden in Montreal were first seriously proposed in 1885 by David Penhallow, the first prof of botany at the city’s McGill University. That year saw the foundation of The Montreal Botanic Garden Association but a suitable site couldn’t be found and the association soon folded. However in 1890 the university leased nine acres and with Penhallow’s help organised a Botanical Garden for use of students and the general public. They didn’t last long either and ceased to exist around the turn of the century.

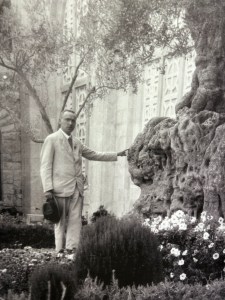

Image from the exhibition about his life at the Marie-Victorin Garden at Kingsey, the town of his birth

Brother Marie-Victorin at the the Botanic Gardens

Despite that, Penhallow’s idea took hold in the mind of Conrad Kerouac, a young man who had joined the Brothers of the Christian Schools, a lay Catholic religious congregation involved in education in 1901, taking the name Brother Marie-Victorin. Two years later and suffering from tuberculosis he was forced to rest, but allowed to take exercise in the grounds of their headquarters on the eastern outskirts of Montreal.

The grounds appear to have had at least formal gardens, although most of that was probably untended, and it was there that Marie-Victorin discovered a love of plants, later writing that [my translation] “like Linnaeus, I saw God in his works; I became passionate about them, an innocent passion that God will forgive me.”

He became a teacher and collected and studied botany in his spare time. This led him to decide to revise the existing inventory of plants in French Canada and to begin a doctoral thesis on the Ferns of Quebec. By 1920 his fame as a botanists was such that he was asked to set up a Botanical Institute at the University of Montreal.

Image from the exhibition about him at the Parc Marie-Victorin

In 1929, he represented the University at the annual meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in South Africa. He took advantage of the opportunity to visit botanical gardens in the major cities of Europe and Africa and came back even more convinced that Montreal had to have one of its own. It would he argued “place Montreal of the map of cities to visit, cities where there is something to please the eye and the spirit.”

The idea was taken up by the Canadian Society for Natural History with which Marie-Victorin was involved and then accepted by the mayor of the city, Camille Houde, who just happened to be one of his former students. Two years later in 1931, then in the midst of the worldwide Great Depression, the city council agreed. The site chosen was that of the very monastery on the east of the city where Marie-Victorin had taken his vows, and which burned down in 1925.

Work started in March 1932 enabling Camilien Houde to provide many jobs for unemployed workers although it was touch and go at the beginning. A small administration building, the boiler house and the first production greenhouses were built but then Camilien Houde was ousted as mayor and work slowed down for the next couple of years, and this meant that much of the site was left in disorder while the greenhouses were used for keeping rabbits!

The administration building – now the Marie-Victorin Building

While this was going on Marie-Victorin published his magnum opus Flore Lauretienne on the botany of the St Lawrence basin, and which remains in print and the standard work even today. [Unfortunately as a result it is not available freely on-line]

Luckily Houde was returned to power and the project resumed at pace with Marie-Victorin appointed the first director of the new garden. During the pause he had already been corresponding with Henry Teuscher, a German/American botanist, horticulturalist and landscape architect, about possible designs. Teuscher drafted his Program for an Ideal Botanical Garden and which became the basis for the Montreal layout and he was asked to become Chief Horticulturist.

Some of the correspondence between the two can be found on the garden’ archive website.

When work restarted 2000 men (and many horses!) were employed for three years, finishing the administration building and production greenhouses, putting in roads and excavating the garden’s two lakes.

Progress was carefully recorded in photographic form, with hundreds of images available via the garden’s archives. Unfortunately they, along with maps, films and other material, were digitised way back in 2011 and the software has not been updated so only some of the archive is still viewable.

The garden soon began to take shape. A nursery was laid out and service greenhouses built and the first gardens organised. These included a large exhibition garden for annuals and herbaceous perennials stretching to nearly 12000 m2 and another almost the same size for economic plants. Both these are still extant and, as you can see from the photos, were looking impressive in late September this year.

The Perennial Garden in 1966

It’s hard to imagine a more symmetrical layout than that of the Perennial Garden, perfectly linear paths and straight-edged borders which are typical of traditional French-style gardens. The structural elements, walls, stairways, pergolas and basins throughout the exhibition gardens have not been altered or moved around which is a tribute to the brilliance of Teuscher’s initial concept structure. However the style of planting has changed , with Teuscher’s original French way of doing things giving way to displays in a much softer English-style.

The perennial garden is laid out as a series of rectangular beds divided by wide gravelled paths. Some sections are devoted to plants that thrive in specific conditions

Part of the economic garden

Things speed up in 1937 with the start of the construction of the Alpine Garden – work wasn’t finished until 1962, because of both the size of the challenge of building “mountains” with very rudimentary resources and the long interruption caused by the Second World War. Clinker and rubble were laid down as a foundation, with hundreds of tons of sedimentary rocks arranged atop them. The rocks’ eroded appearance creates the illusion that they have been here forever.

It is one of the most original designs I’ve seen. No common garden rock garden it covers over 17000m2 and contains over 3000 species arranged on a series of large rocky hillocks which represent 11 different regions of the world from the Andes to the Arctic & the Caucasus to the Drakensburgs.

Some of the various water features, including the cascade garden and the lakes were dug out, and even though traffic noise in 1937 was nothing like what it is today Teuscher was far sighted enough with much of the soil being used to form an embankment alongside the main road which runs past the garden and blocking out noise from the city beyond.

Some of the various water features, including the cascade garden and the lakes were dug out, and even though traffic noise in 1937 was nothing like what it is today Teuscher was far sighted enough with much of the soil being used to form an embankment alongside the main road which runs past the garden and blocking out noise from the city beyond.

All this meant that the gardens could now be opened to school parties during the week and the public on Sundays. They soon proved popular with, on some Sundays between 15 and 20,000 visitors.

A school party working in the greenhouses, 1938

Visitors 1937

The gardens in front of there main entrance, 1938

The following year, 1938, the aquatic gardens and lakes were planted up and as you can see from the aerial shots that year the garden was beginning to take shape properly.

With the outbreak of war in 1939 work slowed considerably, although work had begun on new exhibition greenhouses for public displays. However the recently elected Quebec Premier Adélard Godbout scorned the project as “a few ferns in a Garden ” which were to to cost $11 million, so in 1940, his government ordered work to be stopped on the outdoor gardens and for the steel framework for the exhibition greenhouses to be demolished.

Despite this Marie-Victorin continued to be committed to inspiring the public, especially young people to take an interest in plants and horticulture and so he set up a horticultural school and a programme for Young Gardeners.

Then tragedy struck. Marie-Victorin was returning from a botanising trip with students when the car was involved in an accident and he had a heart attack and died on July 15th, 1944.

Image from La Tribune, 20th

Since then he has become something of a folk hero across Quebec with streets, schools, and of course parks and gardens named in his memory.

I’m not sure though what he’d have made of the giant figure of him that looms over the Parc Marie-Victorin in his home town of Kingsey Falls.

His work was continued by Jacques Rousseau, his assistant, who took over as director of the Garden, and finally oversaw the construction and then opening of the exhibition greenhouses, in 1956 to mark the Botanical Garden’s 25th birthday. Importantly this allowed the Garden to operate year round.

Nevertheless by the 1960s things had entered something of a decline. But then as older readers will remember there was a Universal Exhibition in Montreal in 1967, and followed only 9 years later by the Montreal Olympics, the site for which was next door These two global events focussed attention back on the gardens and provided fresh leadership. It came from Pierre Bourque who at only 23 was put in charge of the maintenance of green spaces for the 1967 World Fair before moving to the Botanical Garden in 1969.

There he drew up plans for continued expansion and some new gardens, including the world’s most northerly Rose Garden which opened in 1976. It works because some of the borders are covered with polyethylene foam blankets so that the temperature beneath the covers never drops below -4°C, meaning that fragile hybrid teas and floribundas can survive Quebec’s harsh winters.

The Flowery Brook was also opened in 1976, around the artificial steam that flowed down from the Alpine garden. The gardens alongside the stream are planted with amongst other things daylilies, iris, hostas, peonies and lilies all of which I discovered are incredibly tough and require no protection at all.

Bourque then became director in 1980 and was the organiser of the first International Floralies Fair held in North America. As a result the garden now developed an international strand with large new gardens inspired by China and Japan, and acquired of substantial collections of Japanese bonsai and Chinese penjing.

I’ve already written earlier and at length about the Chines garden, although the mythical creatures have changed since then, so won’t repeat myself [well that will make a change!] The current set are inspired by China’s oldest compilation of myths, the Classic of Mountains and Seas, written more than 5,000 years ago which is an attempt to provide a geographical account of the country.

I’ve already written earlier and at length about the Chines garden, although the mythical creatures have changed since then, so won’t repeat myself [well that will make a change!] The current set are inspired by China’s oldest compilation of myths, the Classic of Mountains and Seas, written more than 5,000 years ago which is an attempt to provide a geographical account of the country.

Planning for the Japanese Garden began as early as 1967 but didn’t really get very far until the 1980s and it wasn’t finally completed until 1988. It was designed by the important Japanese landscape artist and architect Ken Nakagima. and although it is contemporary rather than traditional in approach it meets all the basic criteria of more traditional gardens, with water, stone and plants combined to create a sense of inner peace. Perhaps the biggest problem Nakagima had to face was choosing plants equivalent to ones used in Japan, but which could cope with Montreal’s more extreme climatic conditions.

Planning for the Japanese Garden began as early as 1967 but didn’t really get very far until the 1980s and it wasn’t finally completed until 1988. It was designed by the important Japanese landscape artist and architect Ken Nakagima. and although it is contemporary rather than traditional in approach it meets all the basic criteria of more traditional gardens, with water, stone and plants combined to create a sense of inner peace. Perhaps the biggest problem Nakagima had to face was choosing plants equivalent to ones used in Japan, but which could cope with Montreal’s more extreme climatic conditions.

Pierre Bourque.

You can hear him talking about his career and views [in Quebecois French] by following this link to Radio Canada

But even after all of Bourque’s work the garden as planed by Marie-Victorin and Teuscher was by no means finished, in particular because the arboretum in northernmost part of the garden was still largely undeveloped. In 1996 a new entrance was opened and a new pavilion – the Tree Pavilion- built as an education and interpretation centre. Quebec has about 70 native tree species but there are now 800 species planted including many which are growing well out of their natural limits of cultivation.

There is also now a First Nations Garden which includes more than 300 different plant species. Designed to evoke a natural environment, it showcases the special bonds between aboriginal peoples and the plant world, particularly for medicinal plants that were important to Iroquoians, Algonquins and Inuit. Something like this was included in Marie-Victorin and Tuescher’s original plans but it didn’t open until 2001 on the occasion of the 300thanniversary ofthe Great Peace of Montreal signed in August of 1701.

There is also now a First Nations Garden which includes more than 300 different plant species. Designed to evoke a natural environment, it showcases the special bonds between aboriginal peoples and the plant world, particularly for medicinal plants that were important to Iroquoians, Algonquins and Inuit. Something like this was included in Marie-Victorin and Tuescher’s original plans but it didn’t open until 2001 on the occasion of the 300thanniversary ofthe Great Peace of Montreal signed in August of 1701.

The gardens now extend to 75 hectares [185 acres] with 30 thematic gardens, an extensive arboretum and ten exhibition greenhouses containing over 22,000 plants species and cultivars. They were officially designated a National Historic Site in 2008.

Clearly in a short [well OK that’s a debatable description] post it’s simply not possible to do it justice but I hope its enough to make you want to find out more about Marie-Victorin and perhaps to explore the gardens website and archives, or maybe one day even visit Montreal and see for yourself.

You must be logged in to post a comment.