In 1926 a 54 year old woman who had inherited a riverside house decided to create a garden. Nothing particularly startling about that although it was thought at the time by some of her friends that she didn’t know the difference between a dandelion and a daisy.

Those friends were soon proved wrong, and over the next thirty years she made a garden that stretched to 20 acres and boasted one of the largest plant collections of her day, including newly introduced rarities such as Meconopsis, the Himalayan Blue Poppy. It was all the more remarkable because it was created in and around a largely coniferous forest and is under snow for about half the year.

Image of Meconopsis and Forget-me-nots by Tim Glass taken from the exhibition

The woman was Elsie Reford, and, as I discovered recently at an exhibition about her life, garden-making was just one of her talents.

So read on to find out more about this extraordinary woman who broke almost every glass ceiling she encountered during her long life, and about her garden now usually better known as Le Jardin de Metis, where an acclaimed international garden festival has been held annually since 2000.

As usual the photos are my own unless otherwise acknowledged. Any historic photos without a link come from images in the exhibition about her in the house. Most of my factual information and quotes come from there too, or from Reford Gardens a book about her garden by her great-grandson Alexander Reford, the former director of the gardens, who I had the pleasure of meeting when I visited.

Of course Elsie started out in life with many advantages. When she was born in 1872 her father, Robert Meighen, was president of the Lake of the Woods Milling Company, the largest milling company in the British Empire. The family lived in Montreal’s Golden Square Mile, where over half of all Canadian wealth resided. Her uncle George Stephen [the future Lord Mount Stephen] was a banking and railway magnate and president of the Canadian Pacific Railway. He was also cousin of Lord Strathcona, the future Canadian High Commissioner in London, who had a great interest in garden-making. [Strathcona features in two previous blogs one for his garden in Scotland and the other for his support for women training in horticulture]

So, unsurprisingly Elsie was well educated and extremely interested in contemporary political and social issues, including business so much so that her great-niece noted she was “the only woman that I have ever known to have read the Keynesian theory of economics from cover to cover.” However there was another more “outdoors” side to her. A redoubtable horsewoman she enjoyed canoeing, as well as fishing and hunting [for more about that see The Elegant Adventurer and Fish Stories]

Elsie and Robert c1923

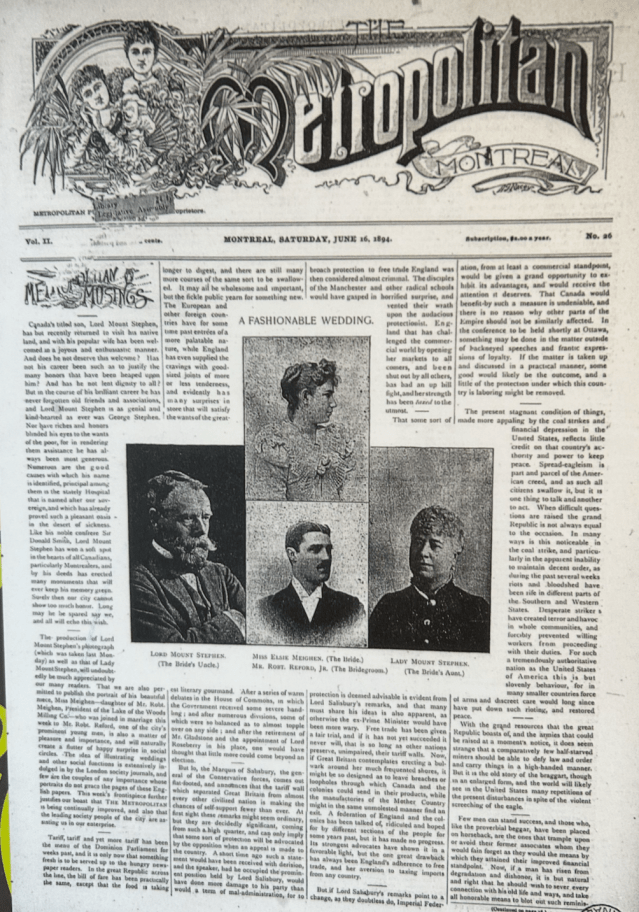

Her wedding to Robert Reford in 1894 made the front page of the Montreal press and after it she began a life of philanthropic, civic and political involvement which included, amongst many other things, c0-founding the Women’s Canadian Club because she felt that her contemporaries were living in a blissful ignorance about matters of public concern which was in the words of her great-grandson Alexander “both unfortunate and disgraceful”.

Her wedding to Robert Reford in 1894 made the front page of the Montreal press and after it she began a life of philanthropic, civic and political involvement which included, amongst many other things, c0-founding the Women’s Canadian Club because she felt that her contemporaries were living in a blissful ignorance about matters of public concern which was in the words of her great-grandson Alexander “both unfortunate and disgraceful”.

Elsie with Lord Grey, and the Mayor of Quebec City until 1905, Simon-Napoléon Parent. 1906.

from The Standard

This led her into the circle of the Governor-General, Lord Grey who gave the inaugural address to the Club. He wrote to her in 1905 saying “I admire the spirit that enables you to ignore tough protests at difficulties and achieve your purpose. Elsie, you will forgive me for writing this but I am ambitious for you, you have it in you to be of great use to your generation.” She later responded: “You are the first person in my life who has ever encouraged me to do anything. Any efforts I have made have been in the face of protests and discouragements. [For more on her work with the Canadian Club see this short video].

Given that she was wholeheartedly involved in so many social and political events she “would probably be horrified to “discover” according to her great-grandson ” that her life is largely remembered today because of the garden she created.”

But much though I’d like to recount more about Elsie’s other activities I’m here to write about the garden and that story really begins in 1918 when she was gifted the riverside estate at Grand Metis on the banks of the St Lawrence by her uncle George Stephen.

In 1874 uncle George had leased the Metis River for $20 p.a largely for its salmon fishing, and then, because the railway ran nearby, in 1886 bought it outright along with surrounding farmland and forest. The following year he built Estevan Lodge, as his base for fishing expeditions. One of his most frequent visitors was Elsie and in 1918 after he moved to Britain he gave the estate to her.

In 1926 at the age of 54, on doctor’s orders Elsie had to abandon salmon fishing as too physically challenging so she turned to gardening. She and Robert extended the lodge and added a second floor, one end of the house overlooking the river was for them and their guests while the other end housed their dozen or so servants.

While some women would have been happy with a charming little country garden, Elsie was not, although to create anything different proved extremely hard work, and not just because of the climate or the fact that the nearest nurseries were hundreds of miles away. There wasn’t even any decent soil because “Estevan has been rather niggardly dealt with” so “when the first garden came to be carved out, it was found there was nothing adequate for horticultural purposes.”

Elsie with her gardeners.

So she set about changing that. Peat and sand were bought in from the surrounding farms and mixed together with gravel from the beach. She needed leaf mould too, but with few deciduous trees there was never enough so she resorted to barter, exchanging salmon for leaves from neighbours’ groves. All this work was done by locals and as Alexander Reford, her great-grandson commented “I kind of wonder if they didn’t think that this middle-aged lady had gone a little bit crazy.” But actually it was a good bargain for them too because it was the time of the Great Depression when work on and for the gardens created employment in an area with very little else by way of work.

Part of her library

Elsie had no training as a landscape architect and did not call on any professionals to help. Instead she read and researched widely. Her library contained books by Gertrude Jekyll and William Robison, notably The English Flower Garden and she clearly took their ideas to heart.

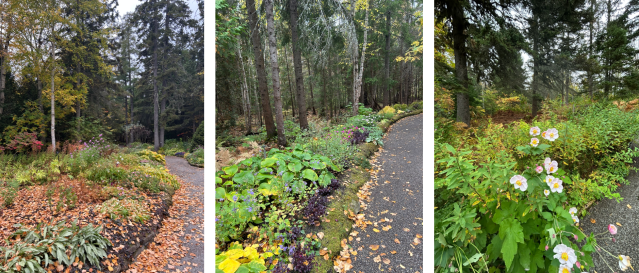

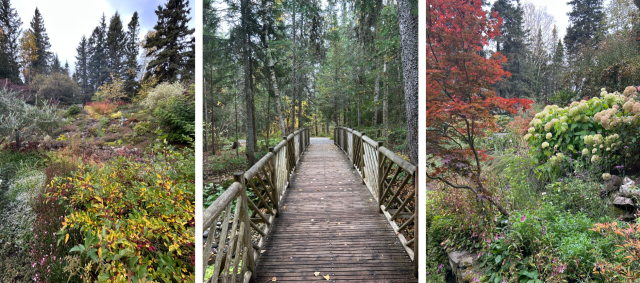

As a result a series of gardens integrate indigenous and “exotic” plants in a design that works and flows with the landscape using simple materials and repeated features such as rustic bridges. As she herself wrote “There are no flower beds, the garden having been fashioned more of less to follow the twisting and curving of the little stream.”

Shelter belts and water created a microclimate while forest paths were edged with raised beds of carefully mixed better quality soil which allowed what was planted to cope in competition with greedy tree roots. The valley of the tiny stream formed the backbone of much of the garden with some sections given over to different species but still working as a single entity.

While the initial impression is very much in the spirit of Robinson’s Wild Garden in fact there are a few more formal features, and the main one of these would not be out of place in any great early 20thc garden in Britain.

This was the Long Walk a herbaceous border 300ft in length, with 12ft beds on either side of a 7ft path of irregular cement shapes made with sand from the beach so as a result tiny shells can be spotted if you look carefully.

Seeing it after having strolled through woodland and stream side areas it was a real surprise, partly because of its formality and partly because even in mid-October it was still full of soft-coloured flowers, with occasional darker highlights. In fact it is a small masterpiece of design with over 400 species and varieties to ensure colour and form for the entire summer season and amazingly her original peonies are still there and flourishing. In particular Elsie was fond of lilies and collected over 60 species, and although she was worried they might not survive the conditions they did, and the Long Walk contains thousands of her favourite lilium regale which “rise in broken waves…to waft their fragrance over the land.”

Seeing it after having strolled through woodland and stream side areas it was a real surprise, partly because of its formality and partly because even in mid-October it was still full of soft-coloured flowers, with occasional darker highlights. In fact it is a small masterpiece of design with over 400 species and varieties to ensure colour and form for the entire summer season and amazingly her original peonies are still there and flourishing. In particular Elsie was fond of lilies and collected over 60 species, and although she was worried they might not survive the conditions they did, and the Long Walk contains thousands of her favourite lilium regale which “rise in broken waves…to waft their fragrance over the land.”

She loved roses too despite the fact that few can withstand the rigours of a Quebec winter, and took great interest in their hybridisation. The development of floribunda roses in Europe in the 1920s led to new varieties which had been bred to withstand the cold of Northern Europe. She acquired plants of, the first noteworthy rose of this type – Else Poulsen – bred by the Danish rosarian Svend Poulsen and it proved up to the task and the garden still uses lots of it today.

She also succeeded when many other experienced plantsmen had failed in transplanting many species thought impossible to grow this far north by experimenting and creating the exact conditions needed so they could be adapted to survive Quebec’s harsher climate. Azaleas, for example, are well outside their natural range at Metis, and it’s thought no-one had tried growing them this far north before Elsie. They grow in a dell at the lowest point in the garden where they flower freely although they rarely achieve a great height. She obtained many of the plants from Britain including some from Lionel Rothschild’s garden at Exbury.

One of her great horticultural success stories was the introduction of meconopsis, the famous blue poppy which was brought back from the Himalayas by Frank Kingdon Ward and first shown at the RHS in 1926. She was amongst the first North American gardeners to try growing them and in 1946 she sent a photograph of hundreds of them to Kingdon Ward telling him “that so well does it grow that to walk along a path between gently sloping banks entirely veiled with the exquisite blue poppies is like going through some ethereal valley in a land of dreams.” This year the gardens have mounted a small but stunning exhibition by Tim Glass of photographs of the blue poppy

Later she decided to collect gentians and created a special gentian garden to house them. This required digging out the clay soil “to a depth of two feet and the first four inches filled in with beach stones about the size of an egg; after that six inches of gravelly grit and the remaining fourteen inches were given a mixture of two parts finely cut leaves, one part and one part of a gritty sand. Into this the Gentians were planted and the whole strewn over with fine gravel.” The first plants came from Britain in 1935 but grew so successfully that within ten years she had over 3000 plants. She wrote about them for New York Botanic Garden in 1945, although they died out during the later period of comparative neglect they are being slowly reintroduced.

The gardens around the house itself were simple and unpretentious, and remain so. On the main front there was originally a belt of cedars around the turning circle, now replaced by plantings of crab apples and species roses. Crab apples do extremely well and there are many around the garden, including an entire garden devoted to them, including many cultivars developed by the Central Experimental Farm in Ottawa in the 1920s.

On the side of the house which looks out onto the St Lawrence there is an “avenue” of dwarf pines cut into mounds, that carried the eye through a gap in the trees to a view of the river. The flag pole you can see at the end of the garden was important to Elsie. According to her grandson Robert William Reford, not only was “Granny Reford” an “impressive lady with many talents, she was a strong believer in the Monarchy and the British Empire. At Metis, the Union Jack was always flown from the flagstaff. When a Cunard ship sailed past, on her way between Montreal and Southampton or Liverpool, the flag would be lowered in salute. The ship would respond with a blast from its foghorn.”

As you can see from the plan I’ve only managed to cover a few sections of the gardens, so I’ve added a few more photos of other areas – and remember these were taken at the very end of the season – but you can find more information and images on the garden’s website, as well as via the references at the end of this post.

As you can probably tell I was quite taken aback by Elsie’s skill as a designer and plantswoman. Of course she didn’t do it alone, employing a head gardener who was helped by 3 or sometimes more assistants, but she was very much hands-on, as she recorded every day in her gardening diary. This drew admiration from her husband too. Writing to a friend he noted: My wife has just come in from gardening and here she is sitting down at her desk at her garden diary. How this woman has this energy to garden and at the end of the day chronicles, I don’t know.” Robert’s part in the garden was to photograph it and the archives contain over 5000 pictures that he took. She herself wrote “I cannot just understand how I have made them what they are,” they “give each day more and more of a thrill”.

Things started to go wrong with the development of hydro-electric schemes on the Metis River, and when a second dam was proposed in 1942 the Refords had to sell the river or have it expropriated. It ended salmon fishing. She found it all heart-breaking so in 1954, three years after the death of her husband Robert, she gifted her estate to her elder son Bruce. But as Alexander commented: “She gave him this place but, of course, as Elsie would do, she doesn’t really give it because she keeps coming during the summer. She lives in the same house as my grandfather and his new wife. You can just imagine the complexity of that kind of situation.”

It only took a couple of years for Bruce, who was a senior figure in the Canadian military, to realise that he did not share his mother’s passion for gardening nor the finances to maintain them so he made a decision that Elsie would have found impossible: to sell up.

At the end of the summer of 1959 Elsie left the house as usual to return to Montreal for the winter. She wrote to her grandson Micahel: “Everything at Estevan has been made so hard for me that I have decided never to return.”

At the end of the summer of 1959 Elsie left the house as usual to return to Montreal for the winter. She wrote to her grandson Micahel: “Everything at Estevan has been made so hard for me that I have decided never to return.”

In 1960, Henry Teuscher, curator of the Montreal Botanical Garden, [see last week’s post for more about him] tried to convince the Quebec government to purchase the estate, arguing:”I am well acquainted with the wonderful garden which Mrs. R.W. Reford has developed at Grand Metis, having visited it a number of times. In my opinion, it is entirely unique in the whole of North America and only in Scotland have I seen anything to compare with it.”

Elsie with her son Eric, accompanied by his wife Katharina and two of their children, Boris and Sonja. Circa 1940

In the end Elsie was reconciled to its fate. She wrote to Michael that “the government has announced that the garden is to be kept up as formerly and the house to serve in time as a museum. I think if these plans are adhered to, that if it were not held for the family as l intended it should be, it all seems better than I had believed would be possible.”

In the end Elsie was reconciled to its fate. She wrote to Michael that “the government has announced that the garden is to be kept up as formerly and the house to serve in time as a museum. I think if these plans are adhered to, that if it were not held for the family as l intended it should be, it all seems better than I had believed would be possible.”

Elsie never did return and died at her home in Montreal in November 1967 aged 95. To my surprise her obituary in The Times [see below] does not mention her gardening interests at all.

From The Times 14th November 1967

The gardens opened to the public in 1962, and by the 1990s were attracting around 100,000 visitors every summer but this did not stop the Quebec government deciding to privatise the gardens in 1994, and if there were no buyers then to close them. The family and community rallied round and formed a friends group, Les Amis des Jardins de Métis, which a non-profit charitable organisation which is now responsible for the preservation and development of the gardens. And very impressive they are too- the gardens were named a national historic site of Canada in 1995 and a heritage site in 2013 by the Government of Quebec. A Conservation Plan was drawn up in 2017.

Apologies that I haven’t got space to talk about the International Garden Festival or other projects that Les Amis are organising so that will have to wait for another post soon.

For more information – for once you’re almost spoiled for choice especially if you speak French. Some of Alexander Reford’s books are easily available in French editions, but it’s difficult to find the English versions, even the latest which coincided with her 150th birthday, Elsie Reford: 150 Objects of Passion is sill not available in Britain. Tele-Quebec produced a short video about it. However Reford Gardens is available via archive.org, as is Les belles de Métis, which although it’s in French has lots of images. He has also set up a website which includes many historic photos of Elsie and the gardens. There are several videos about the gardens including this one in French by him, but plenty of others on YouTube in English and even more there in French.

I have visited the Reford many times and will continue to return. In every season there is something to admire and inspire. Thank you for sharing your experience of visiting the garden. I hope you will be able to return in a different season, perhaps when the blue poppies are in full flower.

What a remarkable woman!