The Majorelle Garden is a tranquil urban oasis in the busy city of Marrakech, in the south of Morocco. It was begun by the French artist Jacques Majorelle in 1924 inspired in part by traditional Moroccan garden design but with some additional touches of his own. His combination of striking planting and a vividly strong colour palette – which includes the garden’s signature colour- Marjorelle Blue – certainly disproves the old adage that “Blue and Green should never be seen”.

The Majorelle Garden is a tranquil urban oasis in the busy city of Marrakech, in the south of Morocco. It was begun by the French artist Jacques Majorelle in 1924 inspired in part by traditional Moroccan garden design but with some additional touches of his own. His combination of striking planting and a vividly strong colour palette – which includes the garden’s signature colour- Marjorelle Blue – certainly disproves the old adage that “Blue and Green should never be seen”.

The garden was rescued from neglect and the threat of development in the 1980s by the fashion designer Yves St Laurent and his partner Pierre Bergé, who carried out major improvements so that it now welcomes about 1.2 million visitors a year and is one of Morocco’s major tourist attractions.

If you read on you’ll see why…

As usual the photos are my own unless otherwise acknowledged.

Jacques Majorelle was born in Nancy the capital of Lorraine in north eastern France in 1886. The city was also a major horticultural centre with a range of well-known nurseries and plant-breeders which helped inspire the artistic world of artists and artisans like his father Louis Majorelle, who was one of the founders of the Art Nouveau movement. He went on to study architecture, before abandoning it in favour of painting, and training first at home in Nancy and then Paris. In 1910 Majorelle visited Egypt and became fascinated with the world of Islam before in 1917 discovering Morocco. He quickly fell in love with Marrakesh whose colours, light and “souks splashing with fertile and happy life” captivated him. Within a few years he had settled there with his wife and made Morocco his home, and its landscapes and people the subject of his paintings. Amazingly what he does not seem to have painted are plants or his own garden.

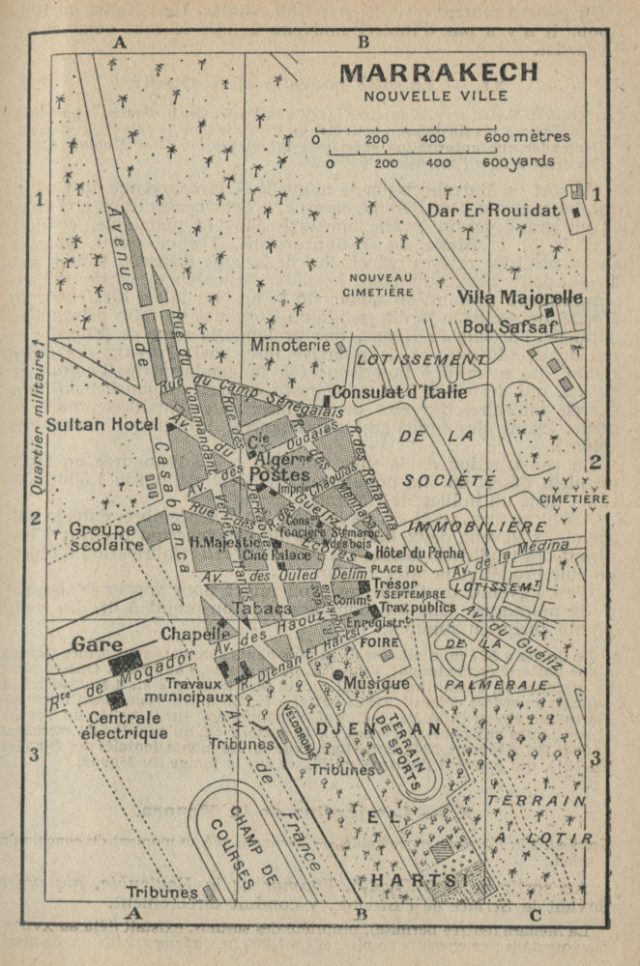

In 1923, Majorelle bought a plot of land of about 1.6 hectares, outside the walled city on the edge of the sand-swept palm forest near the new town/European quarter where he had a house built in Moorish style. Slowly he bought up other plots of land until he had nearly 4 hectares of ground. Architect Paul Sinoir designed a modernist cubist villa for him in 1931, and over the next 30 years while retaining many of the original date palms, Majorelle became a plantaholic, creating a lush garden surrounded by compacted earth walls that became “a cathedral of shapes and colours”.

This was not as easy as it sounds. The city is built in a desert on the edge of the Atlas Mountains with a huge temperature range. Daytimes in high summer can often hit over 40°C, but in the winter nights drop to near freezing. Despite that there are plants that not only survive but thrive and they are what Majorelle chose. Then he started pushing the limits, gradually introducing species from elsewhere in Morocco, then the rest of north Africa then South Africa, and then other arid areas of the world.

Water is crucial throughout the garden for both practical and aesthetic reasons. Majorelle was sensitive to traditional Moroccan agricultural techniques and divided the garden into small irregular areas contained within very low concrete kerbs – maybe only a foot or so above the ground, which could also acted as narrow access ways. This meant that each enclosed planted area could be flood irrigated in turn when necessary from an elaborate system of small canals.

For aesthetics he added a long rill with a tiled pavilion at on one end as well as other water features such as a square tank with a fountain and a large pond containing water lilies and lotus. These all help keep the atmosphere slightly humid, and cooler with the bonus of attracting birds and adding gentle background sound.

As a painter Majorelle had a keen eye for colour too and in particular fell for the cobalt blue which it’s impossible to miss in Morocco because it’s everywhere from ceramics to, Berber clothing and around windows. He chose this blue in preference to white or the more common pinks and ochres used on other Marrakesh buildings and used it on the house and around the garden where it helped intensify the range of greens on the plants.

As a painter Majorelle had a keen eye for colour too and in particular fell for the cobalt blue which it’s impossible to miss in Morocco because it’s everywhere from ceramics to, Berber clothing and around windows. He chose this blue in preference to white or the more common pinks and ochres used on other Marrakesh buildings and used it on the house and around the garden where it helped intensify the range of greens on the plants.

There was one downside with his new garden, because as it grew it became increasingly expensive to maintain, so in 1947 he decided to open the gardens to the public.

Unfortunately things became even more difficult as he got divorced and was forced to sell off much of the land in 1956, and then in 1961 after a serious car accident that led to the amputation of his left leg. He was forced to give up on the estate, and died in Paris the following year.

The Snake House from A Moroccan Passion [full reference below]

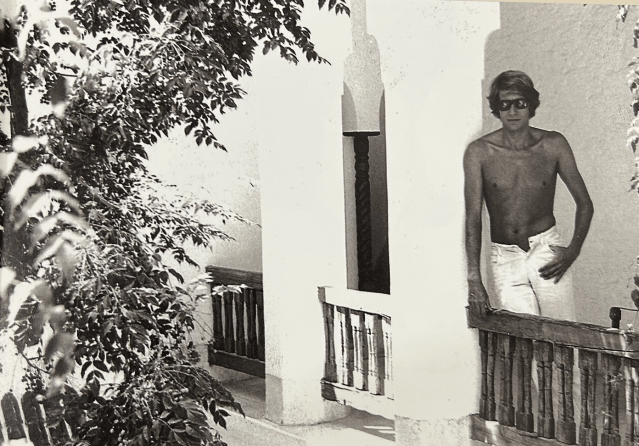

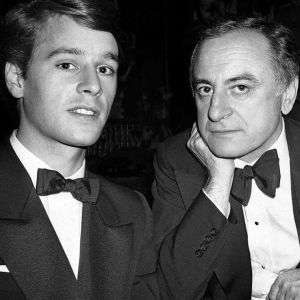

Amongst them were the Paris couturier Yves Saint Laurent and his partner Pierre Bergé. They first visited in 1966 and immediately fell in love with the city and before they left they had bought a house in the Medina.

YSL on the patio there

“When we arrived in Marrekesh, Yves and I were utterly seduced by the beauty and the magic. What we did not expect was that we would fall in love with a small, mysterious garden, painted in the colours of Henri Matisse and secluded in a bamboo forest, all silence, deeply sheltered from noise and wind. This was the Majorelle Garden. Years later, quite by chance, we came into possession of this jewel and set about saving it.” (Pierre Bergé)

“When we arrived in Marrekesh, Yves and I were utterly seduced by the beauty and the magic. What we did not expect was that we would fall in love with a small, mysterious garden, painted in the colours of Henri Matisse and secluded in a bamboo forest, all silence, deeply sheltered from noise and wind. This was the Majorelle Garden. Years later, quite by chance, we came into possession of this jewel and set about saving it.” (Pierre Bergé)

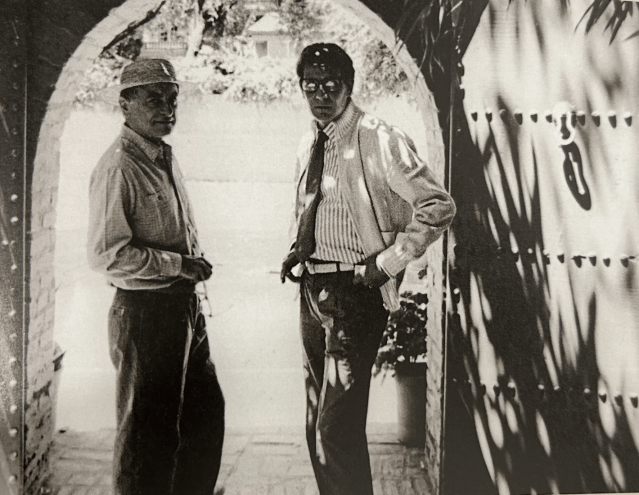

Marrakesh became the second home for the couple, and they visited regularly, eventually moving in 1974 to a house which they named Villa Oasis after a book by Eugene Dabit. It was next door to the Jardin Majorelle whose grounds became a favourite place to walk and became an enormously important source of inspiration for the couturier.

In 1979 they were visited by a young American named Madison Cox who recalls the gardens being striking, but unkempt. Decades later, he is now the Director of the Foundation that owns and manages the garden and its associated museums but still remembers his first impressions: “It was extremely romantic, very overgrown and there were very few visitors. It was a rendezvous for mischievous… It was a place Moroccans could meet. The walkways were poorly kept and the structures were quite dilapidated, but it had a romance. It was very poetic. What was there, that remains, is this extraordinary collection of plants, palm trees and especially cacti and succulent plants that Majorelle collected over the decades.”

When the widow who then owned the property died developers hovered as it would have made a great site for a hotel for the booming tourist trade. Saint Laurent and Bergé moved fast and bought the property to save it and “to make of the Jardin Majorelle the garden that Majorelle himself had dreamed of”.

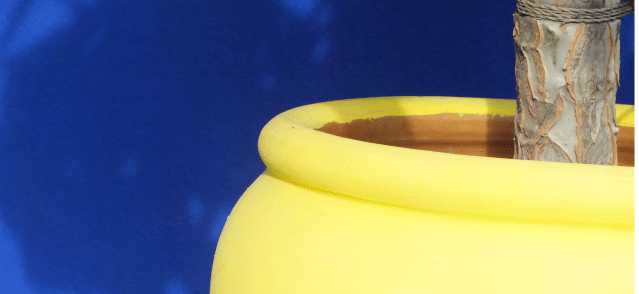

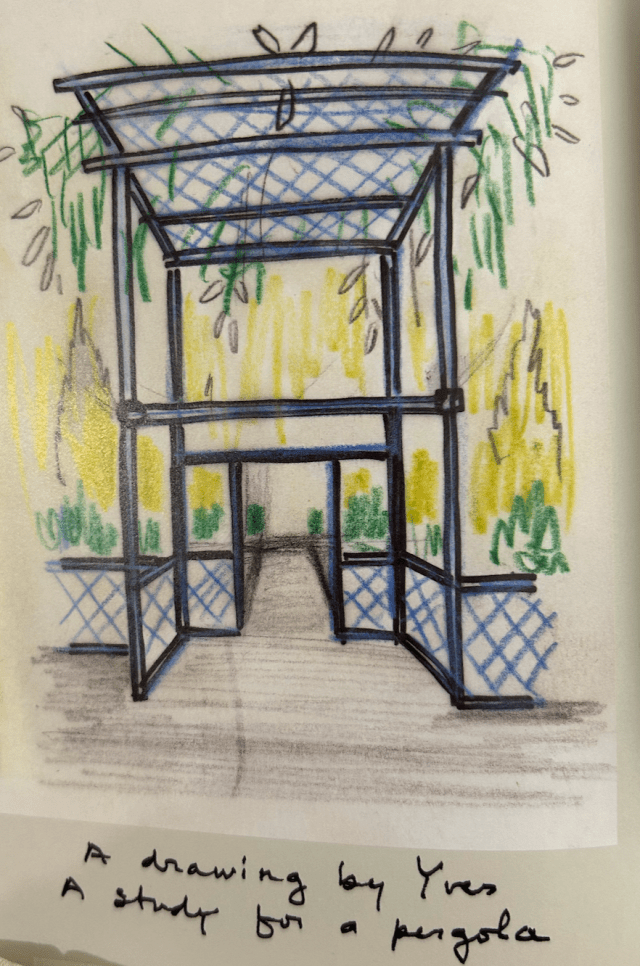

Saint Laurent now added more luminous colours to the garden to counter and complement the Marjorelle Blue. Large pots were painted in vivid yellow, mint, olive and pale blue while some paths were painted red. New structures were added including the central arbour which was inspired by Jean Gallotti’s Le Jardin et la Maison Arabe au Maroc, published in 1926.

Saint Laurent now added more luminous colours to the garden to counter and complement the Marjorelle Blue. Large pots were painted in vivid yellow, mint, olive and pale blue while some paths were painted red. New structures were added including the central arbour which was inspired by Jean Gallotti’s Le Jardin et la Maison Arabe au Maroc, published in 1926.

The plant collection grew too, adding to what had survived from Marjorelle’s time. Apart from the extraordinary array of cactus the stars of the show are dozens of century-old Washingtonia palms, a magnificent Mount Atlas mastic tree (Pistacia atlantica), pencil trees (Euphorbia tirucalli), a Mexican blue palm (Brahea armata) and an elephant’s foot palm (Beaucarnea recurvata).

xxx

Madison Cox who remained a regular visitor had by now established a career as a successful garden designer and in the late 1990s was asked to think about possible alterations and new introductions. These began to be introduced after 2000. His starting point was the continuation of its unique character but adapted to cater for vast numbers of visitors.

He also had to consider its longer term sustainability. Keenly aware that Marrakech is a desert city with only about 4 inches [106 mm] rainfall a year he made the decision to get rid of the the lawns although “We had a lot of resistance from the gardeners because there’s a lot of prestige about having a lawn in Marrakech. It means you can pay for the water required to keep it green.” Nevertheless the lawns went. What also went was a rose garden, which pre-dated Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé and was clearly unsuitable for the climate. It was replaced by a garden of citrus plants of all kinds.

The couple at Majorelle from Moroccan Passion

Yves St Laurent died in 2008 and his ashes were scattered in the Majorelle gardens. Bergé continued to run the gardens until his own death in 2017 when control passed to Madison Cox, who Bergé had married a few days before his demise. His ashes too were scattered in the garden and a Roman column found on a Tangier beach near their home there now stands as a memorial to the two men.

Yves St Laurent died in 2008 and his ashes were scattered in the Majorelle gardens. Bergé continued to run the gardens until his own death in 2017 when control passed to Madison Cox, who Bergé had married a few days before his demise. His ashes too were scattered in the garden and a Roman column found on a Tangier beach near their home there now stands as a memorial to the two men.

Cox’s intentions for the future are clear: The aim is to preserve Marjorelle largely as it is. There are no plans for radical change instead “there’s constant evolution”.

One step on this path was to create a post of Director of Botany which was given to Marc Jeanson from the Natural History Museum in Paris with a brief to identify the plants and spread information about them, the garden and our fragile natural world.” His survey identified around 350 species but the number will grow as the gardens continue to acquire suitable new plants particularly palms, cacti, succulent plants and bamboos and species that are endemic to Morocco.

The latter is part of another gradual change which was to attract more Moroccans to the garden because until the pandemic most of the garden’s 1.5 million annual visitors were international tourists rather than locals. It’s amazing how so many people and plants can fit into a garden squeezed into just about a hectare – 2.4 acres.

I haven’t been for a few years but I remember being really taken aback by the complexity and density of planting, the interplay between light and shade and zing of bright colour which constantly mitigate the range of greens of the plants. The other noticeable thing is that it’s not the sort of garden that can be described easily for a guided tour. But let’s make an attempt, although there’s one by Marc Jeanson that was published in Historic Gardens Review, Issue 44, September 2022, and then put on-line by the Mediterranean Garden Society the following year.

Otherwise who better to describe than Pierre Bergé, the last private owner. Fifteen years ago he described the then fairly nondescript approach: “Close by the Medina, an ordinary street filled with pushcart merchants selling oranges and lemons gives access to a broad path of beaten earth lined with pink laurel and bordered by adobe walls.” It isn’t quite like that now but it still “leads to a blue-brick entrance hung with a green-painted wooden door, which opens on to the garden.” I remember the city being baking hot with fierce sunlight, even in late spring, and then walking in that doorway and being met by a complete change in atmosphere to cool and refreshing, as well as stands of bamboo.

As Bergé said “they come as a surprise in this environment, and the water surrounding them looks quite odd under the African sun. Some of the trees, imported from Malaysia, stand in clumps, so that their green-striped yellow stalks form a kind of palisade.”

After that your eye takes in the polished red concrete paths before being taken aback by the differing shades of green ranging from the “almost blue” of chamaerops palms to the “almost black” of yuccas. Berge is more poetic than me: “the dragon trees a gleaming presence. Bougainvillea mount to the challenge of the pritchardias (Loulou palms), while water lilies spread wide across the surfaces of the fountains. Papyruses, both Egyptian and alternifoliate varieties, sway back and forth, leaving the caladiums and philodendrons to shelter the frogs and water turtles.”

“Now it becomes clear that we are at the home of a painter, in a garden designed, composed, and coloured like a painting. Immediately one thinks of Henri Matisse, for we are indeed at the very centre of a Matisse, soaked in colour – chilly greens, acid yellows, and hot blues. Everything here conjures up painting”

After Bergé’s death the gardens of the Villa Oasis, his former private residence, just a few metres from the main public areas are also sometimes opened to the public. They are more formal and open with paths lined with Washingtonia robusta and four relatively low squares rather like the traditional layout of an Andalusian Moorish garden, each planted with a specific botanical collection.

After Bergé’s death the gardens of the Villa Oasis, his former private residence, just a few metres from the main public areas are also sometimes opened to the public. They are more formal and open with paths lined with Washingtonia robusta and four relatively low squares rather like the traditional layout of an Andalusian Moorish garden, each planted with a specific botanical collection.

The gardens are now owned and managed by the non-profit Fondation Jardin Majorelle, which also supports dozens of Moroccan institutions in the field of culture, health and education. It also trains gardeners in ecological management as well as specific skills, for example in succulent and cacti management.

The site is now also home to two small museums, one in honour of Yves St Laurent, and a sister museum to its namesake in Paris, but which also especially recognising the inspiration he found in Morocco, and includes library, much of which is dedicated to the world of gardens, landscapes and botany. The other named after Pierre Bergé is dedicated to Berber arts and culture which the couple championed and collected.

I’m unfortunately going to end on a bit of a depressing note. During my research for this post I began to read recent reviews of the gardens and unsurprisingly given its small size, narrow paths and the enormous numbers of visitors many people complain about overcrowding… summed up by this quote on TripAdvisor: “It was hard to soak in the beauty of these famous gardens so filled with photoshoots and queues for a pose in the most Insta-famous spots.“

I’m unfortunately going to end on a bit of a depressing note. During my research for this post I began to read recent reviews of the gardens and unsurprisingly given its small size, narrow paths and the enormous numbers of visitors many people complain about overcrowding… summed up by this quote on TripAdvisor: “It was hard to soak in the beauty of these famous gardens so filled with photoshoots and queues for a pose in the most Insta-famous spots.“

So, Whilst it’s true that Bergé and YSL saved and enhanced “Majorelle’s greatest work of art” ie his garden it’s unfortunately also true that in a way they were too successful and there’s a danger that it will go the way of several other great gardens that simply cannot cope with the crowds and so destroy the magic of the place…and what a pity that would be.

For more information good palaces to start are: Marjorelle, A Moroccan Oasis, by Pierre Bergé & Madison Cox, 1999, and Yves Saint Laurent: A Moroccan Passion by Pierre Bergé, 2013; Unfortunately neither are available on-line. It’s also worth looking at the websites of the Foundation and the various museums associated with them.

For more information good palaces to start are: Marjorelle, A Moroccan Oasis, by Pierre Bergé & Madison Cox, 1999, and Yves Saint Laurent: A Moroccan Passion by Pierre Bergé, 2013; Unfortunately neither are available on-line. It’s also worth looking at the websites of the Foundation and the various museums associated with them.

For more on Jacques Majorelle’s artwork take a look at Les Orientalistes ; There’s also an interesting interview with the normally reclusive Madison Cox ; and if you want to see more pictures then try looking at at the Trip Advisor gallery for Majorelle which has over 38,000 photos!

Majorelle From Google Earth

You must be logged in to post a comment.