Gardeners who are famous to one generation often don’t stay in the public memory of the next. So while we still treasure Ellen Willmott, Gertrude Jekyll and William Robinson, one of their highly regarded contemporaries has vanished from the face of horticulture history, although in his day, he was as esteemed as any of them. That’s probably because he wrote no books.

If you’ve heard of Charles Wolley Dod then you’re either a fanatical reader of Victorian gardening magazines, or maybe a fanatical plant specialist who remembers a cultivar named after him or his garden or perhaps a member of Cheshire Gardens Trust… but if you have no idea who I’m talking about then why not read on and find out more about him…

Charles Wolley [pronounced “Wooly”] was born in 1826, went to Cambridge and then in 1850 landed a job at Eton where he taught for nearly 30 years. His father had been a clergyman and so perhaps it’s no surprise that he was ordained deacon himself while at Eton, although he never proceeded to the priesthood. He married Frances Parker, the heiress to her grandfather Thomas Crew Dod of Edge Hall near Malpas in Cheshire, and changed his name to Wolley Dod when he and his wife inherited.

He retired in 1879 and moved to Edge Hall. The house originally dated from the early 17thc but had been remodelled in the 1720s, with further additions in the 1790s. Now with money, time and space on his hands he could indulge in his passion for gardening.

He threw himself into local life too, for example taking an active part in the Chester Society of Natural Science and on their 1880 day trip out into the countryside where there were “many rare plants” , offering prizes to “those members who collected greatest number.” To our eyes very unfriendly to nature but then of course a perfectly acceptable thing to do – think of pteridomania or fern fever around the same time..

But even by then Wolley Dod’s name had begun to appear in the horticultural press. A short article in Gardeners Chronicle for Sept 17th 1879 about mulleins revealed his interest in and knowledge of native plants and the possibilities of hybridising them for garden use. A few months later he was writing about Circuta virosa, otherwise known as cowbane or northern water hemlock. The following year it was a short note about primulas, which revealed he had already started making an alpine garden at Edge Hall, and an account of ferns encountered on a ramble in the Lake District. He also followed up his notes about mulleins with a recommendation for Verbascum phoenicum of which he had “several hundred in flower”. From then on he appears regularly in its columns.

Within four years of his retirement the garden had become sufficiently established and renowned to get not one but two visits from Gardeners Chronicle. The first in May 18892 was an account by George Wilson [a great plantsman and the owner of Oakwood the garden that was later to become RHS Wisley] entitled “Among the Hardy Plants”.

Having been prepared by Wolley-Dod’s notes in the papers Wilson was expecting “an interesting garden”, but was clearly more than impressed Overwhelmed by the sheer number of plants he decided to be selective in what he described, concentrating on two aspects. Firstly on how “native plants” were grown ” to show them in their proper character and full beauty”, and secondly on the alpine garden. “There is a very great deal of rockwork, the stone for which has been carefully studied and selected ; some is set apart for small and difficult alpines, where every chance is given them, but in places nearer the drive, and therefore more in view, large flowering masses are allowed to luxuriate over the great stones with a beautiful effect. On one border there is a plant …Gentiana verna ; a patch not as large as a hand was simply all blue, with more than a hundred flowers expanded. He also particularly noticed “Lilium pardalinum, in height and number of flowers much finer than I had ever succeeded in growing in the open border.”

The folloowing month Wolley Dod himself wrote at length about “Hardy Plants at Edge” before in October there was a second much longer account of the gardens which formed the lead article in that issue of the magazine

The folloowing month Wolley Dod himself wrote at length about “Hardy Plants at Edge” before in October there was a second much longer account of the gardens which formed the lead article in that issue of the magazine

As you can see from the extract on the right the anonymous reporter spent “a whole working day, from fore-noon till evening, devoted to the inspection – some 40 pages of closely written notes containing the record of the days work”

Annoyingly despite all the many words without any images it’s difficult to imagine quite what it was like. However, what comes through loud and clear is that Wolley Dod was a keen plantsman, and even though the soil at Edge was heavy clay and poorly drained he had quickly built up a collection of plants – mainly hardy herbaceous plants, bulbs and alpines – which filled the 4 acres immediately round the house.

Alpines being one of his particular favourites he thought “one ought to demolish an old and construct a new rockery every year” Having recently holidayed in Llandudno the latest rockery was “a low mound of nearly uniform height throughout, and constructed of thick rugged slabs of mountain limestone, such as that which forms the Great Orme’s Head.”

“Plants were everywhere. They line the sides of the carriage way, they fill borders on borders, they occupy bed after bed. They clothe the slopes, they are dotted on the lawn, they edge their way in up to the very hall-door, they are invading the kitchen garden at such a rate that fruit and vegetables are ousted by their more showy looking neighbours.and who will regret it? Cabbages can be seen any day and procured everywhere, but the site of such a collection as this is not an every day occurrence.”

His watchwords were “Propagate, propagate, propagate,”

That obsession with propagation, and the desire to grow everything he could find, meant there was clearly not enough space in the original garden so it started to spread into the surrounding 80 acre park. Eventually the planting covered 10 acres.

There “the woods in spring are carpeted first with primroses and wood anemones then with wild hyacinths and pink Campion while later there is a tall growth of campanula latifolia“.

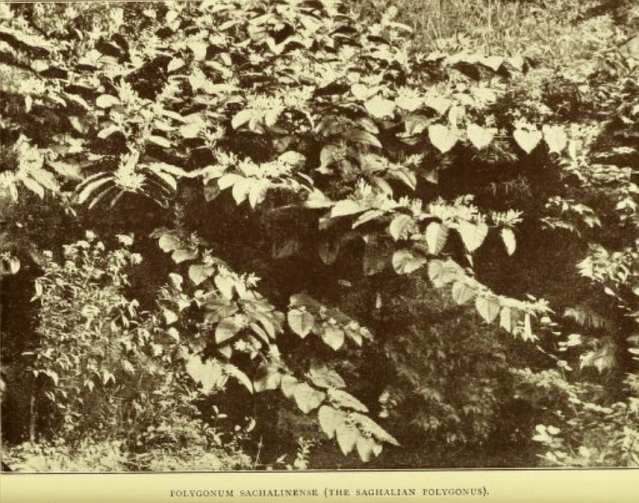

Then comes something of a surprise to the modern reader when it is revealed that Wolley Dod had “large breadths of Polygonum cuspidatum which has been successfully planted to supersede Nettles.” The surprise is, of course, because P.cuspidautm is Japanese Knotweed. Of course Wolley Dod could be forgiven since it was being widely promoted as an attractive hardy perennial addition to the herbaceous border or the wider garden, and as I showed in an earlier post was highly recommended by writers including William Robinson, Gertrude Jekyll and Henry Cook. Given how hard it is to eradicate I wonder how much is still there.

From A Gloucestershire Wild Garden , Henry Cook, 1903

Wolley Dod and Edge Hall made many more appearances in gardening magazines because he began contributing and corresponding on a regular basis on a wide range of subjects, including a few quirky ones, such as a detailed account, (including pricing) of how to make “cheap and durable, if not elegant, plant labels” which led to considerable correspondence. Another was on the use of tobacco dust to deter slugs. Most of his articles for Gardeners Chronicle were of course were about hardy herbaceous plants, in what became a regular column called “The Herbaceous Border”.

One article on spring flowers at Edge Hall for the Gardener’s Chronicle had a very telling postscript added by the editor: “a description of the garden was given in our second volume for 1882 “but the number of variety of plants grown is so large that the description written for one week would have to be superseded the next. The garden is one of those places which makes the ordinary visitor feel his ignorance somewhat unpleasantly.” Perhaps that’s because he didn’t go along with the fashion for carpet bedding or formal regular borders which “oppress you with a tremendous place of colour, [because] the whole thing is done for effect.” Instead ” the plants are multitudinous and of different sizes and sorts; they are not turned out dealt with en masse, but each one has been separately thought about.” That’s because “Edge Hall garden is one of those in which the hardy flowers of the northern world are grown in numbers for the owner’s delight and the good of his friends,”

One article on spring flowers at Edge Hall for the Gardener’s Chronicle had a very telling postscript added by the editor: “a description of the garden was given in our second volume for 1882 “but the number of variety of plants grown is so large that the description written for one week would have to be superseded the next. The garden is one of those places which makes the ordinary visitor feel his ignorance somewhat unpleasantly.” Perhaps that’s because he didn’t go along with the fashion for carpet bedding or formal regular borders which “oppress you with a tremendous place of colour, [because] the whole thing is done for effect.” Instead ” the plants are multitudinous and of different sizes and sorts; they are not turned out dealt with en masse, but each one has been separately thought about.” That’s because “Edge Hall garden is one of those in which the hardy flowers of the northern world are grown in numbers for the owner’s delight and the good of his friends,”

Samuel Arnott visited in 1891 and wrote a laudatory description of Edge Hall’s “Hardy Flowers”for The Journal of Horticulture which after describing the vast array of flowers ends: “I have said little of the courtesy and kindness shown to me by the owner of this beautiful place. I have said nothing of the vast stores of knowledge regarding his favourite flowers which he possesses, and which he does not regard as for his own benefit alone, but which he is ever ready to impart to others in such a manner as to make a walk through the gardens in Mr. Wolley Dod’s company so interesting and so edifying that I was loth to tear myself away from a guide so courteous and a scene so fair. …I have many “ sunny memories of other gardens,” but none will linger longer in my mind than that of my visit to Edge Hall, with its incomparable flowers which seem to laugh to scorn my feeble attempts to describe their beauties, but which make one long for the inspiration of some of the poets who can so worthily sing of their loveliness”.

It’s clear from all these reports that Wolley Dod was clearly regarded as an expert by his contemporaries, and for being generous with both time and plants. Perhaps as a result he was later to become one of the first recipients of the RHS’s Victoria Medal of Honour in 1897.

It’s clear from all these reports that Wolley Dod was clearly regarded as an expert by his contemporaries, and for being generous with both time and plants. Perhaps as a result he was later to become one of the first recipients of the RHS’s Victoria Medal of Honour in 1897.

He was friends with William Robinson and Gertrude Jekyll who called him “an experienced gardener and the kindest of instructors”, and even sent him proofs of her books for comments.

Robinson also sent a reporter to Edge Hall for an article in The Garden and featured it in The English Flower Garden in 1900. Sadly there were only two photographs from all the reports

The original 60 recipients of the Victoria Medal of Honour in 1897. Wolley Dod is no.21 [4th from the left in the 3rd rank down] image scanned from the RHS 1997 commemorative booklet about the VMH

Apart from hardy herbaceous plants and alpines Wolley Dod’s other main interests were bulbs especially daffodils and lilies. He had a greenhouse devoted to lilies but as far as I can see no hothouses. He was, according to David Willis author of Yellow Fever, the “most avid of all the late 19th century daffodil correspondents, and was also a daffodil collector in mainland Europe.” Amongst his many articles for Gardeners Chronicle were several on daffodil diseases. He was responsible for the re-introduction of N. pallidiflorus in 1882, and N. triandrus var.loiseleurii (calathinus) from the Îsles of Glénan at about the same time. and is also known to have introduced at least five daffodils :Philip Hurt ,Blunder-Bore, Cormoran, Hwyfa, and Og, King of Bashan.

He grew several unusual bulbs including one, Zigadenus elegans, a relation of camassia, that had been imported from the Rockies. Perhaps the reason its not better known is because every part of the plant is poisonous and its nicknamed “the Death Camus”

His last article, about “native wild plants for the rock garden” was published posthumously in The Garden in August 1904.

Several plants were supposed to be either bred by him or named in his honour, although only one is listed in the modern PlantFinder: ‘Wolley Dod’s’ Rose. This is a hybrid of unknown origin but thought likely to have been between a Rosa alba and R. pomifera.

It scientific description is usually R.Pomifera ‘Duplex’ although I’ve also seen it described as R. villosa ‘Duplex’. Wolley. Dod himself offers no clue and it’s not mentioned in any of his articles. However it was illustrated by Alfred Parsons in Ellen Willmott’s great book of roses Genus Rosa, from a specimen that came from the gardens at Edge Hall. There’s no way of knowing whether Wolley Dod deliberately bred it or whether it was a chance sport or seedling, or whether it was just Ellen Willmott remembering an old and recently departed friend. We’ll probably never know.

Willmott also named a daffodil Charles Wolley Dod which was given an Award of Merit in 1900. Other plants named for him or Edge Hall included a saxifrage and Chrysanthemum Edge Hall which was being sold by Peter Barr in 1890, while the most popular was probably Heuchera Edge Hall which was still being listed until the late 1950s. Unfortunately I can’t find images of any of the rest of them!

His death in June 1904 will, said his lengthy obituary in Gardeners Chronicle, “create widespread regret among a large and influential circle; for, indeed, his position in the horticultural world was unique. He was in correspondence with almost every amateur gardener in the kingdom, and with not a few of the professional growers also.  He was an excellent cultivator, careful to .study the requirements and, we may say, the caprices of his favourites… Truly in later times horticulture has not sustained a more severe loss than in the person of Charles Wolley Dod.”

He was an excellent cultivator, careful to .study the requirements and, we may say, the caprices of his favourites… Truly in later times horticulture has not sustained a more severe loss than in the person of Charles Wolley Dod.”

But sadly after that Wolley Dod was quickly forgotten, and while the house at Edge Hall is listed at Grade 2* the gardens are not listed so I suspect probably just got abandoned and I’ve been unable to find any reference to their present state. As Alex Pankhurst, author of Who Does Your Garden Grow (1992) concludes her short entry on him “that present day gardeners have now forgotten is our loss too.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.