MERRY CHRISTMAS!

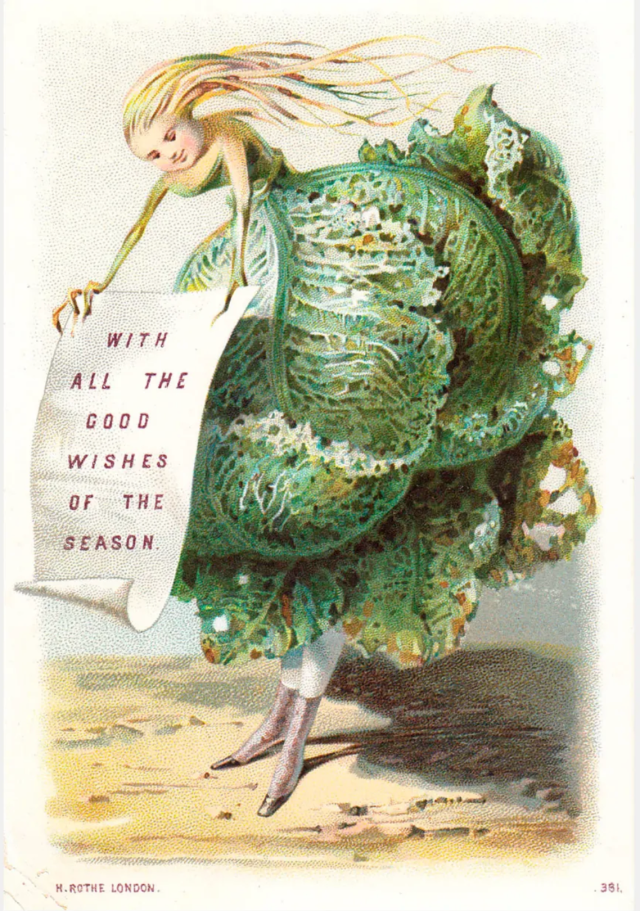

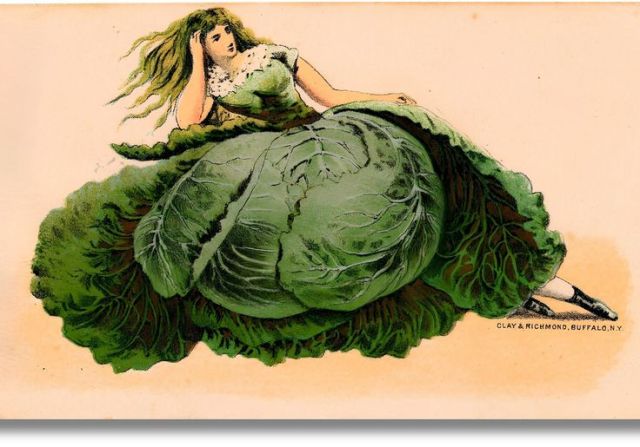

A Christmas Cabbage

“The approach of Christmas time is already heralded by profuse displays, in every variety of design and colouring, of those cheerful cards which it has become so fashionable now-a-days to exchange between families and friends at the close of the year.” So began an article in the press on 4th December 1880.

It went on…” of the entire host of card makers we must give the palm, alike for originality of invention, exquisite taste in design, and admirable finish in execution, to Mr Herman Rothe, 11 King Street, Covent Garden, London.”

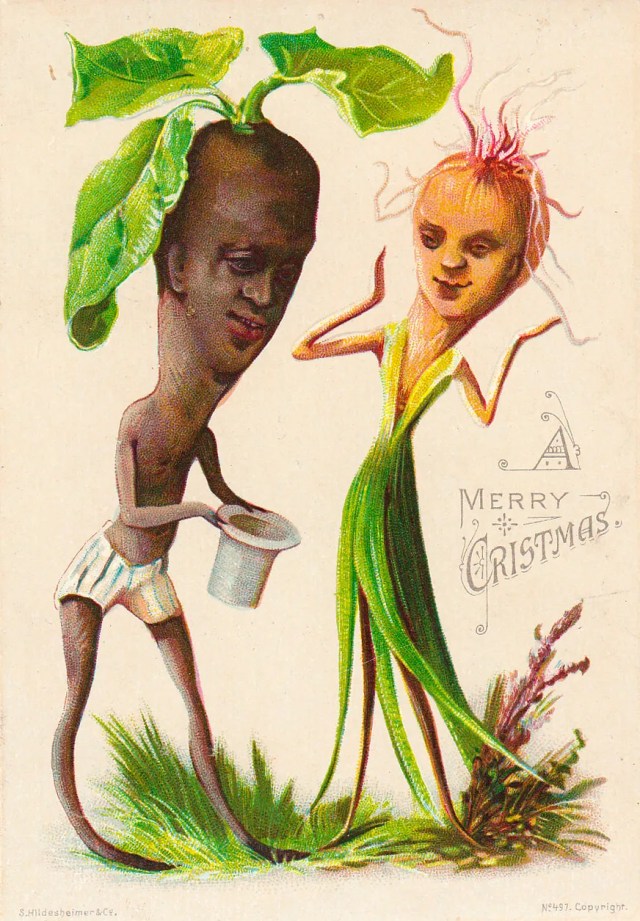

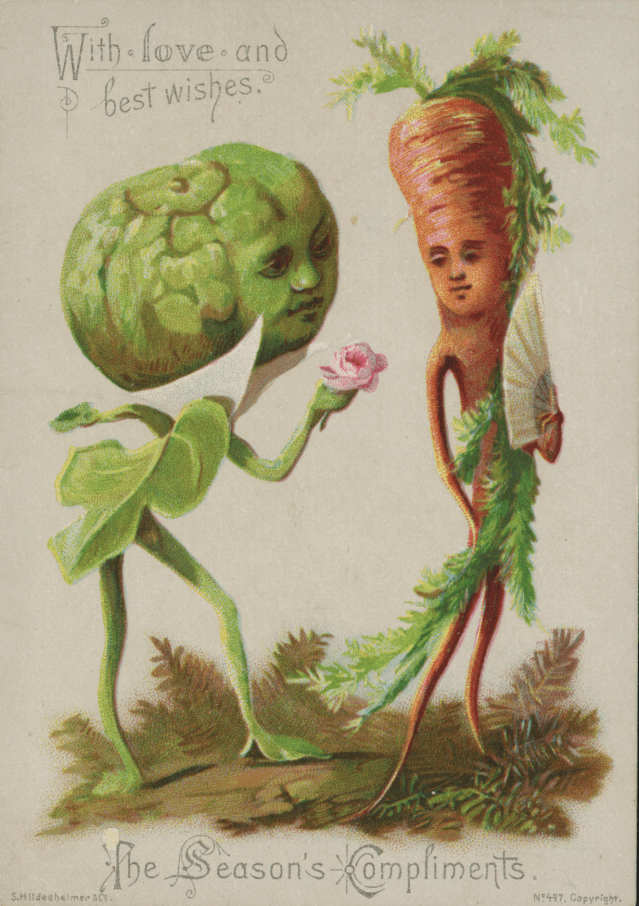

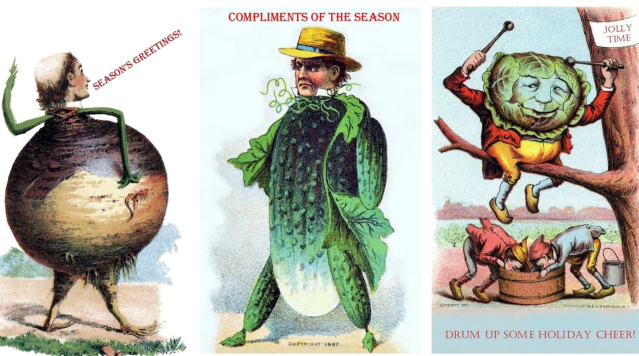

I suspect it would be difficult to find anything showing more “originality of invention” than a set of bizarre humanised vegetables offering Christmas Greetings…although whether they show “exquisite taste in design” might be debatable!

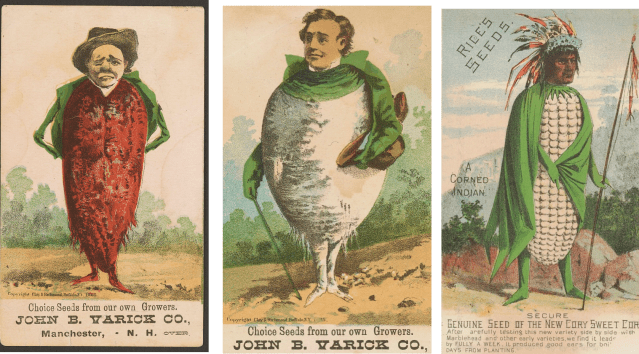

A dandy of a beetroot and a well-dressed potato offering seasonal greetings – cards by Herman Rothe

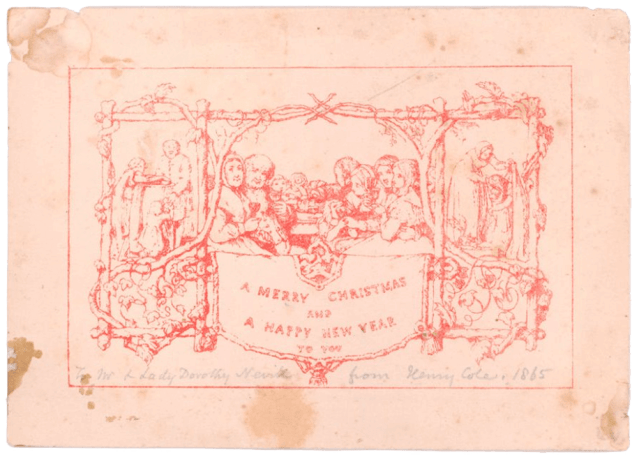

The commercialisation of Christmas had begun soon after the first cards were designed and sent by Sir Henry Cole the first director of the V&A in 1843.

One of 5 Proofs of the First Xmas Card, Inscribed to Lady Dorothy Nevill [coincidentally a gardener previously covered in this earlier post] ] by Henry Cole

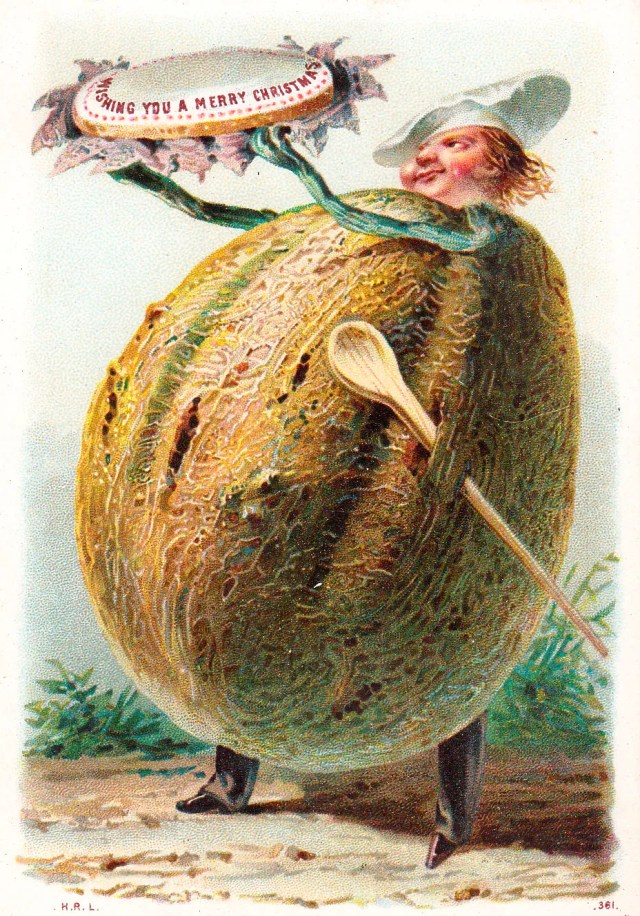

Merry Christmas from a melon!

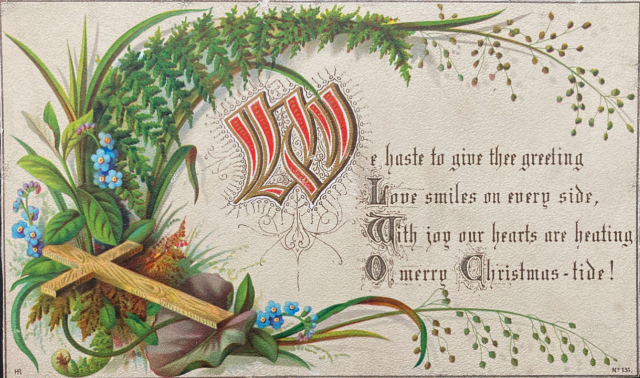

With the development of cheaper, colour printing by the 1850s and 1860s, such things as Christmas cards and Christmas annuals and gift-books became popular with the growing middle class. However, like Dickens’ Christmas stories, these early Christmas cards are usually secular, rather than particularly related to the Christmas story which is a bit strange given the religious fervour of the Victorian era.

Nevertheless by the 1870s this trend was firmly established and cards tended to be, to our eyes at least, distinctly unseasonal, unfestive and often bizarre …and surely none could be weirder than a series of cards produced in the later 19thc by a pioneering young publisher Herman Rothe.

and it wasn’t only vegetables; les that were used for rather strange seasonal greetings

As you might have guessed from his name, Hans Phillipp Herman Rothe was German, and probably from Bavaria, where he was born in about 1845. He came to London in 1872 to run the London agency of the influential Leipzig-based art publishing house of Friedrich Bruckmann, and was, according to his obituary in the printing and publishing trade journal The Bookseller, quickly successful in making it profitable. A few years later he branched out on his own alongside the agency “and by industry and sound discretion rapidly laid the foundations of a prosperous business” publishing cards, prints and other stationery goods.

He was obviously not alone in producing this sort of material and the pages of newspapers and magazines were full of adverts from many other publishers, but Rothe’s somehow stood out. This maybe because he seems to have sent samples to editors all over the country hoping they would mention his offerings favourably:

One example I found was from the Bristol Mercury on 29th Nov 1880 which carried a small article headed Christmas and New Year Cards. “Amongst the specimens of art in this direction which have reached us, a high class must be assigned, both for elegance of design and beauty of execution, to the productions issued by Mr. Herman Rothe, publisher of 11,King-street, Covent-garden, London.Though the grotesque element is by no means absent, and the votaries of fun will find amongst these cards several pictures adapted to their tastes, the prevailing characteristic is a refined grace that will make Mr. Rothe’s seasonable issues peculiarly acceptable in many quarters.

“Some of the pictorial representations are of the choicest quality, and we may particularly notice a set of tastefully arranged floral groups, with the accompaniment of pretty verses and suitable mottoes, beautifully, printed on satin. There are others in which a cross emblazoned in gold and bearing mottoes connected with the holiest aspirations of the season is entwined with choicest flowers.

“Some of the pictorial representations are of the choicest quality, and we may particularly notice a set of tastefully arranged floral groups, with the accompaniment of pretty verses and suitable mottoes, beautifully, printed on satin. There are others in which a cross emblazoned in gold and bearing mottoes connected with the holiest aspirations of the season is entwined with choicest flowers.

The conventional and time-honoured salutations and good wishes are fully represented, and special commendation is due to a very graceful set depicting the four seasons, with the accompaniment of Shakespearian and other verse. Uncommonly pretty, too, are a couple of sunny portraits of fair maidens, which are the bearers of new year greetings.”

Unfortunately I can’t find much trace of these more refined designs. However, “Many of the minor cards show much originality. There is, for instance, one set charmingly illustrative of the four aces, while others provoke a laugh by their amusing adaptations from the vegetable world. In fact, in making a selection of these pretty media of intersalutation, Mr. Rothe’s meritorious, productions cannot fail to obtain a large share of admiring notice.”

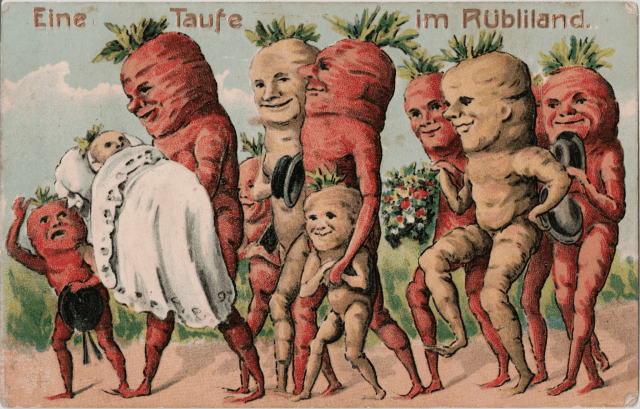

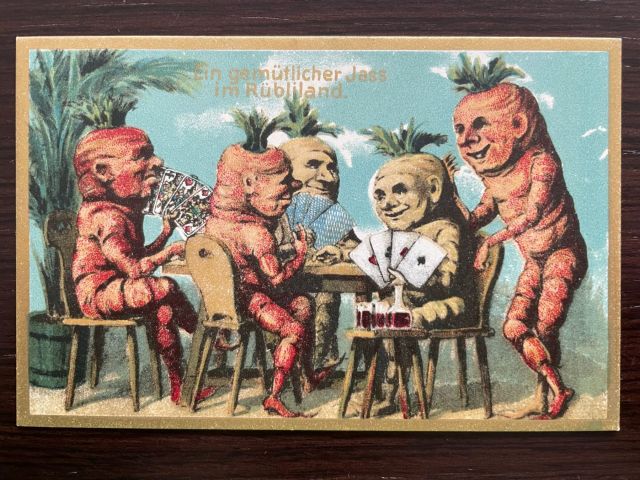

I suspect the origin of the anthropomorphic vegetable Christmas cards comes from the German-speaking world. Unfortunately because cards of all kinds are almost impossible to date easily, it’s difficult to know the exact chronology. Certainly most of the dated examples I’ve seen are from later than Rothe’s day. However in Switzerland and southern Germany, there was certainly a long tradition of such imagery, with at least 9 publishers of these cards so its possible he had seen some there and “borrowed” the idea and then adapted it for use at Christmas. The likely origin of at least the idea comes from the rich vegetable-growing Swiss canton of Aargau which has been nicknamed Rüebliland or carrot land, and where the Rüeblitorte or a sort of carrot cake is the local speciality. No-one is quite sure why!

Carrots were not the only vegetable that was humanised in these comic prints and cards.

one of Hildesheimer’s Christmas cards

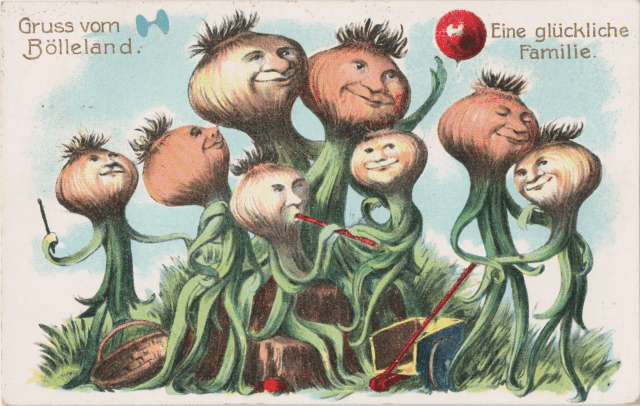

Onions. or Bolle in German were also given human form, and over the borders in southern German with its big beer drinking tradition radishes, particularly the much larger Daikon black radish, which are a popular accompanying snack were also transformed.

and another by Hildesheimer

Another German printer, Siegmund Hildesheimer settled in Manchester in 1870s and was producing other cards in the same spirit as well producing advertising cards and then postcards. His brother Albert did the same but partnership with William Faulkner ing London

At the same time there’s a long tradition elsewhere in Europe, particularly France of using vegetable and fruit to caricature and satirise humans and some of their characteristics.

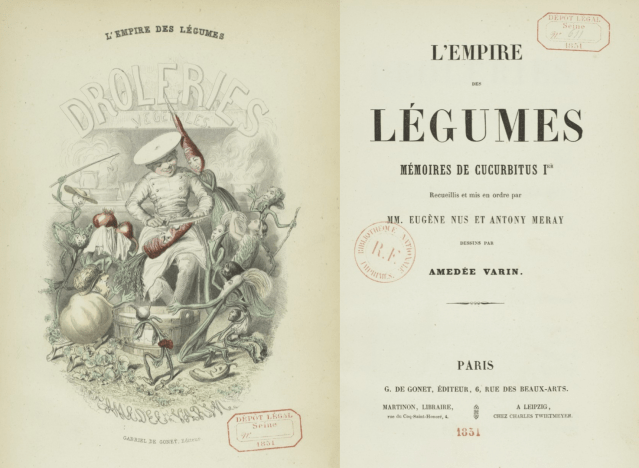

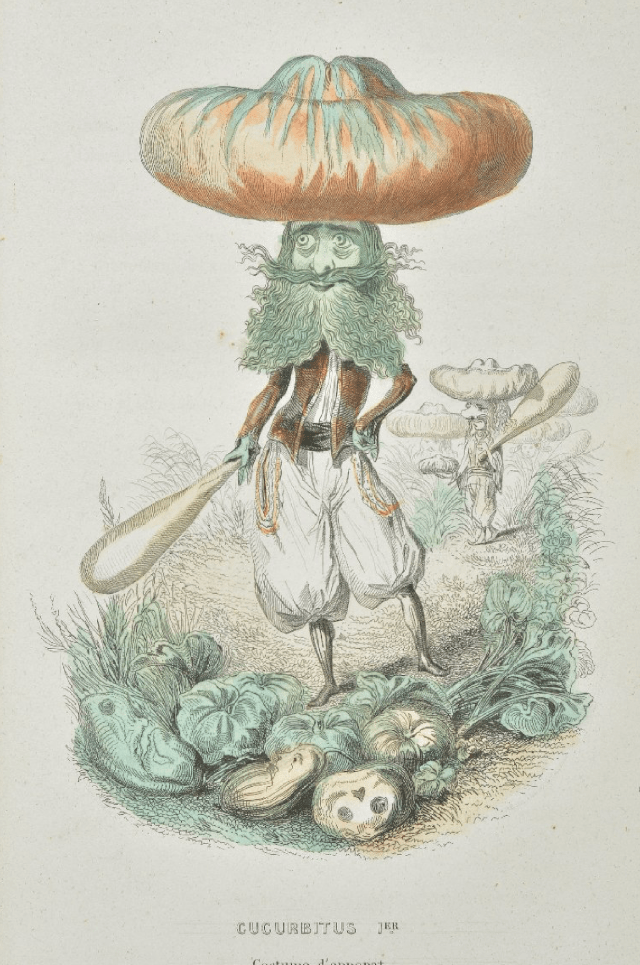

A really good example of this is the Empire of Vegetables which has humorous text by Eugène Nus and Antony Méray, and plates by Amédée Varin, which was first published in 1851. It’s a moral tale apparently meant for children but with adult political satire. The empire is ruled over by “Cucurbitus I” thought to be a thinly veiled caricature of Napoleon III.

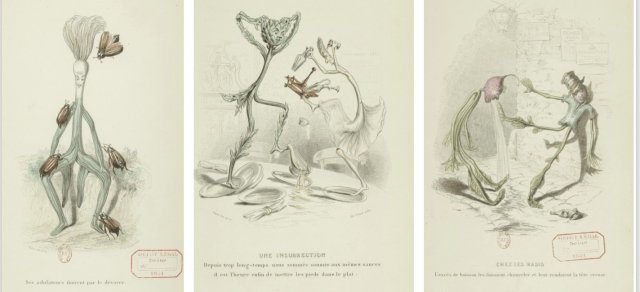

Cucurbitus had never liked people. They were, he thought “only counterfeit vegetables” so one day he wandered off into the countryside to find new “rooted friends”. He’s away for more than seven years and in the process he finds a whole range of vegetables who are used to exemplify and explore human traits, with often sharp commentary, both visual and verbal. Nineteenth century French political humour doesn’t translate easily but the pictures tell a thousand words each.

“Comme quoi les enfants viennent sous les choux” or how children come from under the cabbages ie the equivalent of children coming from under gooseberry bushes

The Paris bourgeoisie in all their finery

We have middle class Parisians metamorphosed into fat round pumpkins or melons and Parliament being addressed by a carrot and plenty more…

The Parliamentary carrot – speaking for three hours without a break

Unfortunately there isn’t an English translation otherwise I’d happily write a post about the rest of the characters, but I’ll add some more images below.

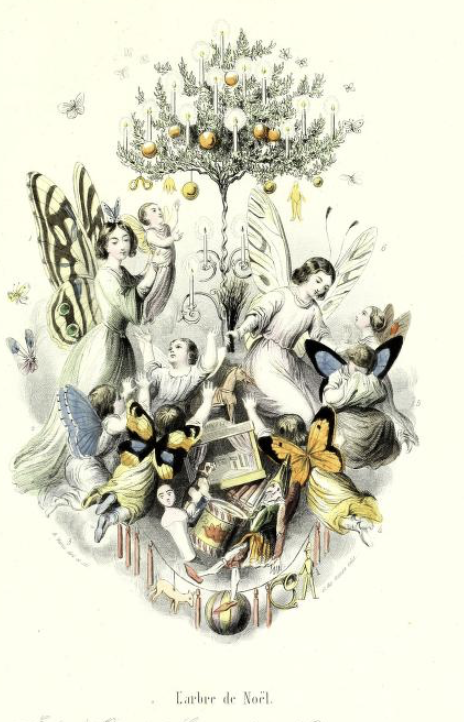

This wasn’t the trio’s only excursion into the fantastic – they also had insect and butterfly people in ‘Les Papillons’ – which like l’Empire is often seen as one of the precursors of Surrealism.

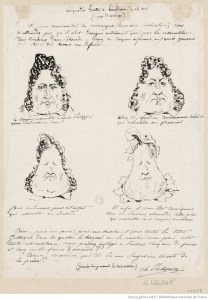

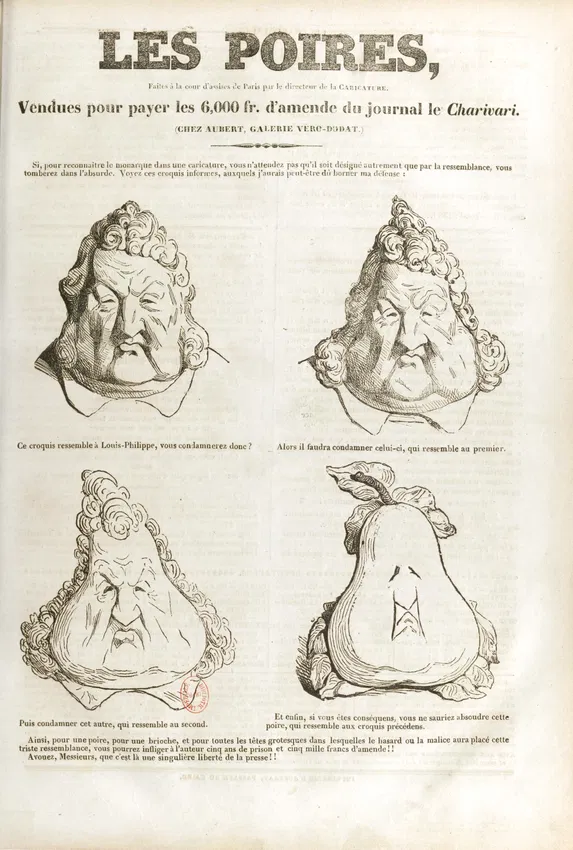

And too there was the famous satirical transmogrification of Louis Philippe from monarch into a pear. It started as a quick sketch in a courtroom, but the artist and the journal it was published in were prosecuted and fined heavily and the poster above produced to raise funds to pay their fine.

And too there was the famous satirical transmogrification of Louis Philippe from monarch into a pear. It started as a quick sketch in a courtroom, but the artist and the journal it was published in were prosecuted and fined heavily and the poster above produced to raise funds to pay their fine.

The joke is that not only did Louis Philippe look rather pear-like in both figure and face but the word “poire” in French not only means the fruit but also a simpleton in slang.

At the same time as Rothe and H were was producing their cards several American publishers began to do the same, with one firm in particular Clay & Richmond of Buffalo making anthropomorphic vegetable cards, prints, trade cards and advertising material their speciality. They were founded in 1877, and were eventually taken over and renamed the Niagara Lithographic Company in 1896. They published similar if not identical cards to Rothe. but whether they copied his lead or perhaps drew on the memories of German or Swiss immigrants is unclear. As far as I can see nobody else other than Herman Rothe turned these ideas into Christmas Cards

Although It’s difficult to know quite why Vegetable people became a popular subject especially in the last couple of decades of the century, they became a combination of eccentric personality-types and healthy produce with a comical twist. These caricatures are often pictured with props including hats, walking sticks, cigars, umbrellas, gardening tools, or musical instruments.

Rothe’s designs were all given a catalogue number which can be found in the bottom right hand corner, and they run in to the hundreds. Luckily quite a few cards have survived because they were framed or collected in albums and added to scrapbooks. There may have been a class element in this because George V’s wife, Queen Mary kept an album [now in the British Museum] but there are no such humorous cards in it.

There is one problem with ascribing the trend purely to Herman Rothe, much though I’d like to. That’s because the few dateable examples, both from Britain and America seem to be post-1880 and most are post-1885. The reason it’s a problem is because Rothe died in January 1881 at his home above the shop at i1, King Street, Covent Garden.

“A slight cold, supposed to have been caught at the funeral of one of his children, became the germ of a malignant fever, which within a few days proved fatal.” However his business “will be conducted in all respects as hitherto, under the same style and title.”

It’s possible that was still trading for about another 10 years so Rothe’s cards could actually have been issued by his successors and not him, because they continued to use his name. However there is another printer/publisher. J.L. Schippers, using the same King Street premises who were also issuing cards who may have taken over his stock and designs. We’ll probably never know but as I said most of the dateable ones are likely to have been produced in the years after the end of his business.

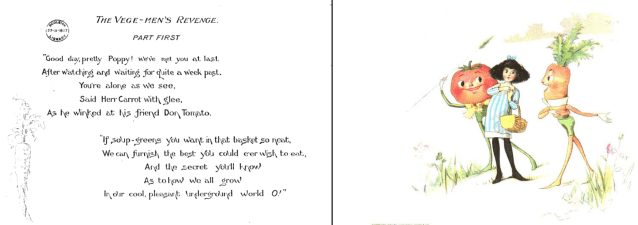

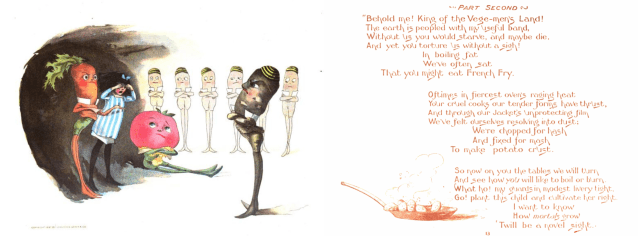

The fashion seems to have finished almost as quickly as it started and I haven’t been able to find many later spin-offs apart from a book for children The Vegeman’s Revenge by Bertha Upton. published in 1897.

Rothe was, we are assured in his obituary, “an upright and honourable man of business, and a most generous employer; and beneath a surface of unassuming good nature, was a clever linguist and more accomplished scholar than was suspected by most of those who knew him.” Sadly his legacy is now largely a collection of humanised vegetables – but maybe there are worse things to be remembered by!

There’s not really anywhere else that offers more information, although there are a few short articles about Rothe’s vegetable cards including this one in The World of Interiors.

You must be logged in to post a comment.