HAPPY NEW YEAR!

Are you one of those lucky people who’ve been given a cyclamen for Christmas? Or maybe that should be unlucky people because many of us find they can be difficult to keep alive for longer than one season. Maybe that’s a good reason to ask who on earth thought that a plant from dry eastern Mediterranean mountainsides would make suitable easy-to-grow houseplants?

What is the history of the colourful “festive” cyclamen?

In short – how did we get from the delicate little plants above to this…

The images unless otherwise acknowledged come from one of the commercial catalogues listed further down the page.

The images unless otherwise acknowledged come from one of the commercial catalogues listed further down the page.

First the basics: there are around 23 different species of cyclamen [I’ve seen between 20 and 25 listed in various places] which believe it or not are members of the wider Primrose family – the Primulaceae. Most are found in Greece and Turkey, with others originating elsewhere across the Mediterranean region from the Balearics in the west, through to the Caucasus Mountains in the east, and with one outlier recently found in northern Somalia. Most species display a lot of variability in the wild, but although they look delicate they areal generally extremely tough and resilient, growing in what for most plants are adverse conditions.

The name Cyclamen originates from the ancient Greek plant name ‘Kyklaminas’ (‘Kyklos’), meaning: circle or disc, referring to the flattish round tubers which are actually swollen underground stems. It was given to them by Joseph Pitton de Tournefort around 1700, and confirmed by Linaneaus in his Species Plantarum in 1753. Both the flowers and leaves grow direct from the tuber. After flowering, the stalk often twists downwards into a spiral, allowing the seed capsule to disyribute the seed away from the plant, so as a result they spread quite rapidly in the wild.

The name Cyclamen originates from the ancient Greek plant name ‘Kyklaminas’ (‘Kyklos’), meaning: circle or disc, referring to the flattish round tubers which are actually swollen underground stems. It was given to them by Joseph Pitton de Tournefort around 1700, and confirmed by Linaneaus in his Species Plantarum in 1753. Both the flowers and leaves grow direct from the tuber. After flowering, the stalk often twists downwards into a spiral, allowing the seed capsule to disyribute the seed away from the plant, so as a result they spread quite rapidly in the wild.

Cyclamen are commonly known across much of European as sowbread or swine bread because it was thought that pigs find the tubers tasty to eat, although they contain saponins which are actually mildly toxic to humans. However they are also utilized in medicine, particularly for treating sinus congestion!

Cyclamen are commonly known across much of European as sowbread or swine bread because it was thought that pigs find the tubers tasty to eat, although they contain saponins which are actually mildly toxic to humans. However they are also utilized in medicine, particularly for treating sinus congestion!

While several species – notably C. coum, and C. hederifolium are good for garden use in temperate climates like Britain only one- the Persian cyclamen – C persicum – is usually grown as a houseplant and that the one that’s the main focus for today’s post.

The first thing to point out is that unlike most other cultivated plants where cross-species hybridisation is common, C. persicum and has proved virtually impossible to cross with other cyclamen species. As a result all the variations in shape, size and colour of modern strains are derived from the humble wild plant which suggests it has enormous genetic variability.

Don’t be deceived into thinking that its name tells you where the plant came from originally. C.persicum has nothing to do with Persia [modern Iran] and instead it is found in southern and south-eastern Turkey, Cyprus and the Levant. while the only cyclamen native to Iran are forms of C. coum. How and when it reached Britain is unknown but the most likely explanation is that it came via the good offices of merchants in the Levant and Turkey Companies in the late 16thc, and so was simply assumed to have come from Persia.

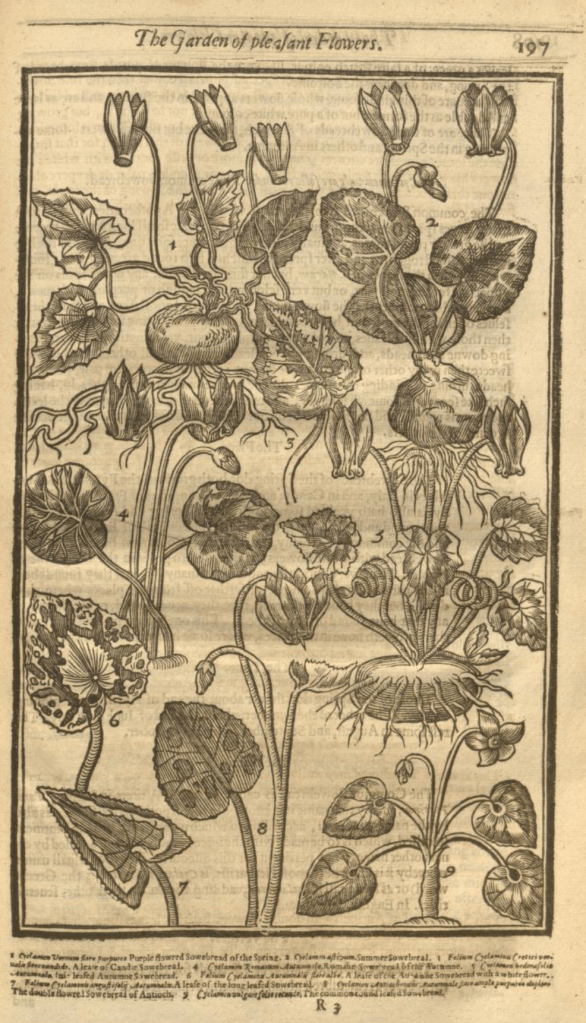

It’s definitely in Britain by 1629 at the latest because it appears in John Parkinson as ‘The Sowebread of Antioch”. It was probably in the nursery of Pierre Morin in Paris as early as 1620, and definitely in the Jardin du Roi in Paris by 1651 with three different forms listed in their 1665 catalogue.

In Britain Sir Thomas Hanmer in his Garden Book of 1659 refers to ‘The Cyclamen of Persia which ‘flowers most of the winter and is rare with us”. He also talks of other cyclamen from Lebanon and Antioch in Syria.

It had reached Leiden’s botanic garden by 1687 while Chelsea Physic Garden was growing a strongly scented white flowered plant from Cyprus which was listed by Philip Miller in his 1768 Gardeners Dictionary.

Propagation of new plants was then a slow business with seeds taking 3-4 years to flower after germination. However in the 1820s an Isleworth nurserymen, John Wilmot, seems to have forced cyclamen to flower more quickly sowing seed immediately and then not allowing the tubers the rest period they would have in the wild. This reduced the time between germination and flowering to around 15 months. Others copied him and by the 1850s cyclamen joined the long list of plants that were being widely hybridised by enterprising commercial nurserymen and enthusiastic amateurs.

A similar story could soon be told across Western Europe too. What all the early breeders were trying to achieve was a greater range of flower colours than just white and soft pinks, and larger flowers. At this stage scent and leaf variations do not seem to have been important criteria.

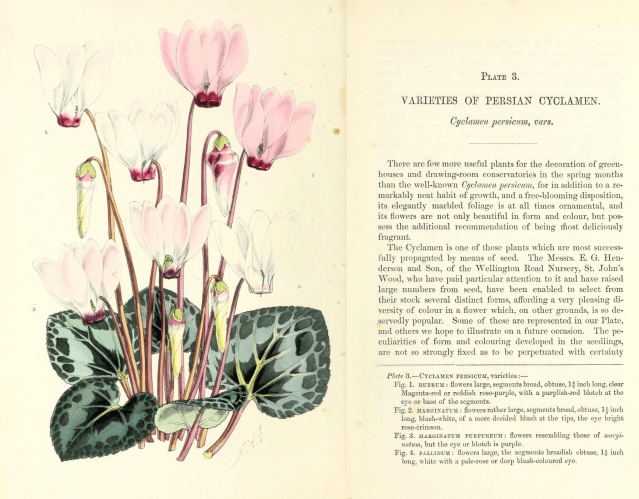

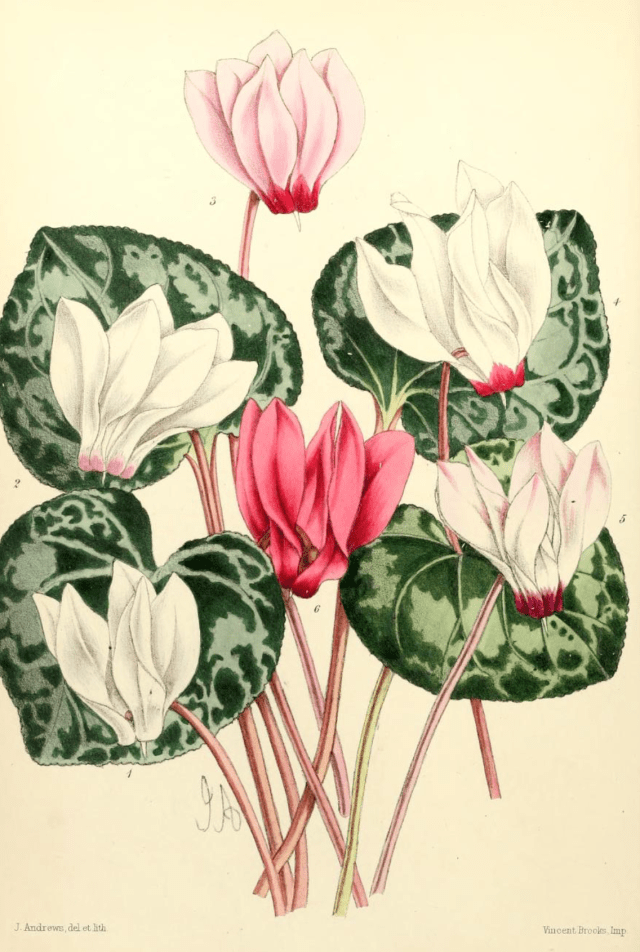

In Britain the pioneer was Edward Henderson a nurseryman from St Johns Wood. In 1840 he bought plants from the Netherlands, selected seedlings and eventually introduced a range of mainly pale coloured cultivars similar to the colours found in the wild but luckily also with a few darker shades. Some of these were also shown in his Illustrated Bouquet of 1861 as well as the first issue of the new Floral Magazine the same year.

There were plenty of other reports in the gardening press around this time that show he was not alone in exhibiting and winning prizes for new strains of C.persicum.

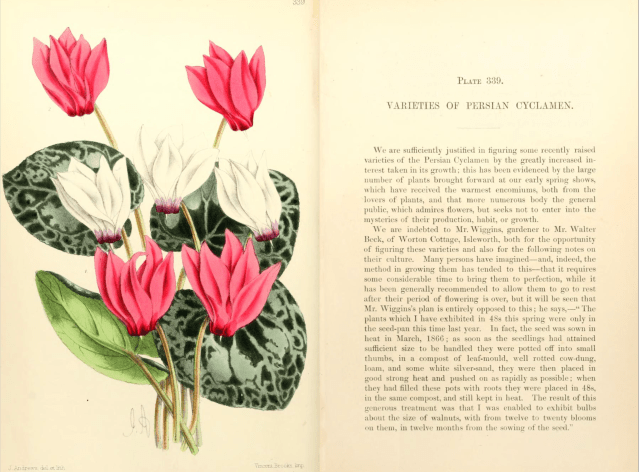

The Floral Magazine in 1867, for example, carried a plate of some recently raised varieties which they said reflected “greatly increased interest” in cyclamen “evidenced by the large number of plants brought forward at our early spring shows, which have received the warmest encomiums, both from the lovers of plants, and that more numerous body the general public, which admires flowers, but seeks not to enter into the mysteries of their production, habit, or growth.”

Those illustrated had been bred by Mr J Wiggins, gardener to Walter Beck of Worton Cottage, Isleworth. As the accompanying text says Wiggins had further reduced the time from germination to flowering which enabled him “to exhibit bulbs about the size of walnuts, with from twelve to twenty blooms on them, in twelve months.”

The following year the magazine published another plate of new varieties because “there was not, during this present spring, any collection of plants that elicited more admiration or warmer eulogiums than they did, and comparing the two plates will show “that great advance has been obtained in the variety of colouring introduced.” However the big problem was that none of them came true from seed.

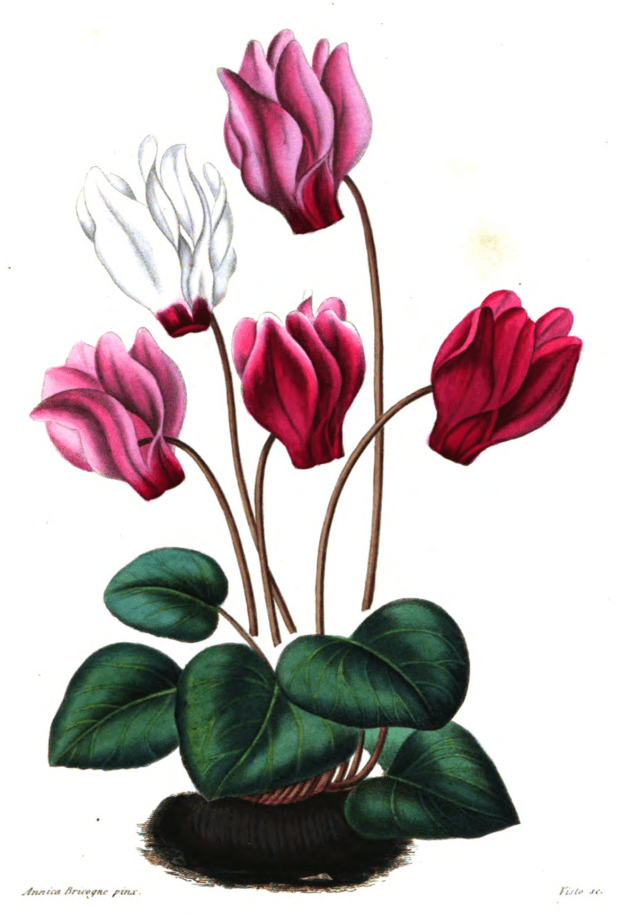

Meanwhile on the continent, Paris nurseryman M. Fournier, spent more than twenty years working to improve the wild forms and by 1853 was able to offer nine different sorts ranging from pure white to reddish purple, although again they still didn’t come true from seed. Another French pioneer was Charles Truffaut of Versailles, whose business founded in 1824 is still going strong who is known to have raised two thousand plants yearly.

Germany was the other main centre with the catalogue of the Erfurt nursery of Haage & Schmidt having sixteen different forms in a wide range of shades by 1863 including some claimed to have slightly larger flowers or marginal markings. Unfortunately there are no known illustrations to verify this.

What eluded all these earlier hybridisers was a true red cyclamen. Haage & Schmidt claim to have created one in 1868 with a variety they named Wilhelm I. which they described as „deep red” although from the images which survive that seems to have been a bit of wishful thinking with the flowers appearing purple with a deep purple base rather true red.

Up until this point all of the new cultivars had small flowers similar to the wild species and it wasn’t until the 1860s that Suttons of Reading first managed to breeding some plants with larger flowers, although it wasn’t until 1870 that there was a real breakthrough on that front.

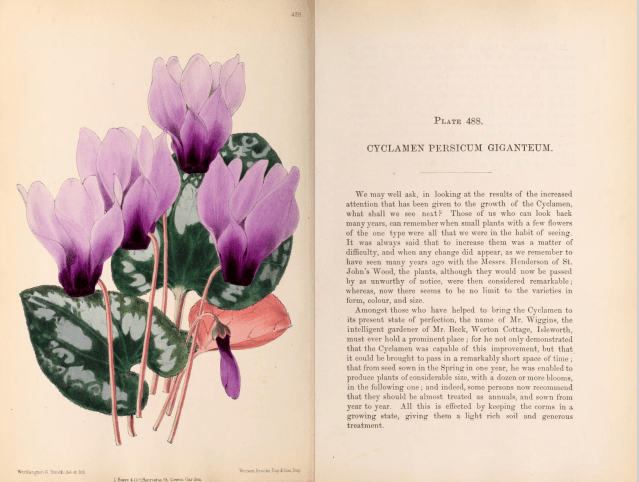

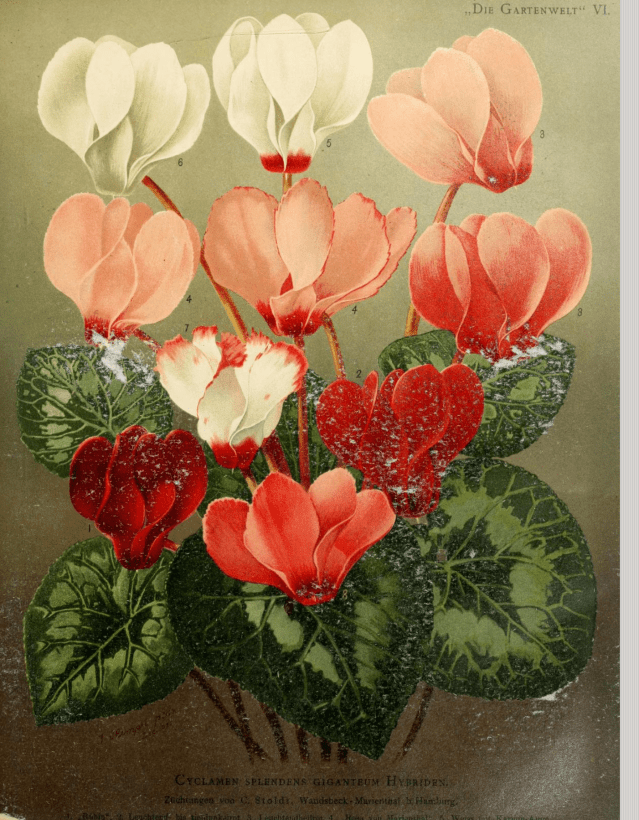

That year the Floral Magazine published a plate showing C.Giganteum Rubrum which had been raised by a Mr Edmonds who was an ex-employee of Henderson’s nursery before setting up a rival establishment at Hayes. [If anyone knows more about Edmonds please let me know] The Floral Magazine noted that : “In the size of its flower it surpasses all that have been hitherto raised, while their colour is of a bright rich rosy purple. The foliage is also remarkably fine and there can be little doubt that it indicates a ‘Break’ from whence we may expect great things.”

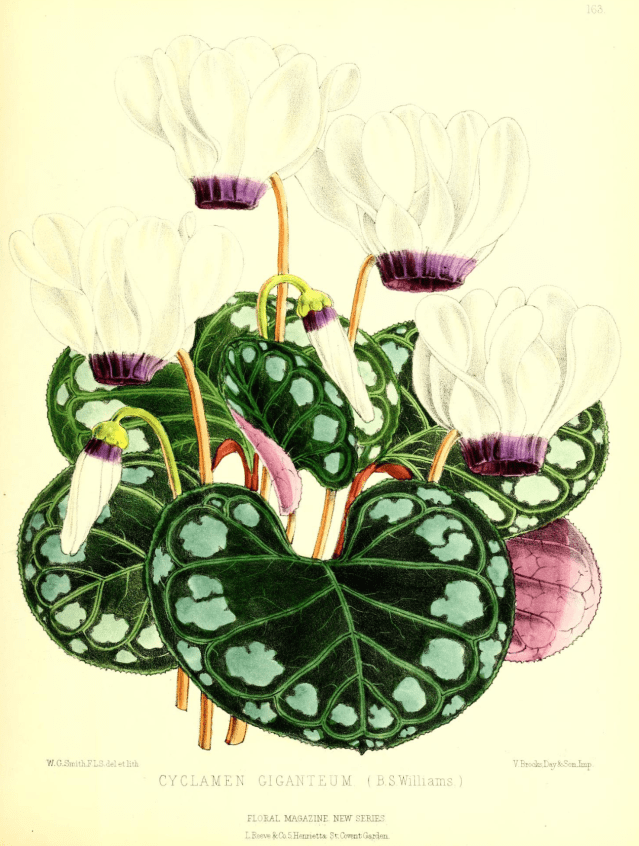

Great things did indeed follow. Commercial nurserymen including Veitch, Britains largest nursery business, and Benjamin Williams also got involved in hybridising using Giganteum as a parent. By 1875 Williams had bred a giant white flower which had a large purple base, and six to eight “petals”. He also exhibited abroad and his exhibit of cyclamens on the Flower-show at Amsterdam in 1877 caused a minor sensation with many of his plants being bought for high prices by continental nurseries for use in their own breeding programmes. At the same time his nursery was selling seeds supplied by Wiggins.

Of course there’s always a downside to such improvements, and for the Giganteum strain it was that it grew out of proportion with straggly long leaves that made the plant ungainly. Edmonds then managed to counter that with his compactum Magnificum, [don’t you just love the superlatives – nothing like a bit of hyperbole] “a plant of good compact habit with large white flowers with a crimson base.

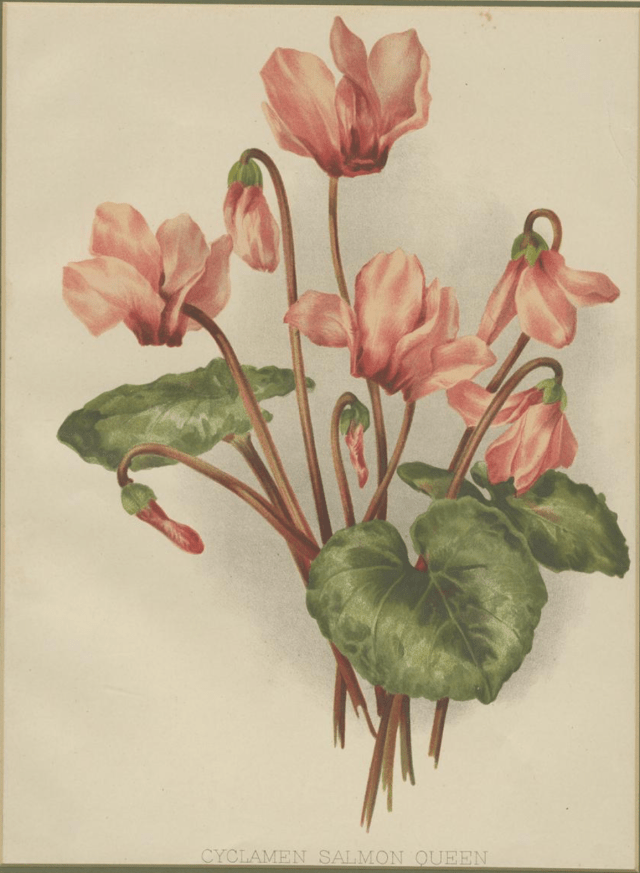

Where Edmonds, Wiggins and Williams led others followed. The gardening press in the last decades of the century is full of exhibitions and awards for cyclamen from quite a number of amateurs or non-commercial gardeners. More and more strains and even some named varieties appeared across the whole colour range but still with the exception of really dark shades of purple and red. Then in 1894 Suttons of Reading introduced a completely new colour break with “Salmon Queen”. Unfortunately the new strain had small flowers and a poor habit but, again, it proved a starting point for further improvements. Despite that, The Garden that year included the comment : “It appears that the raisers of new Cyclamen have really arrived at a stage when to attempt further advance in size of bloom or variety in colouring means a downward step.”

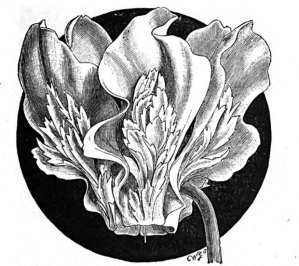

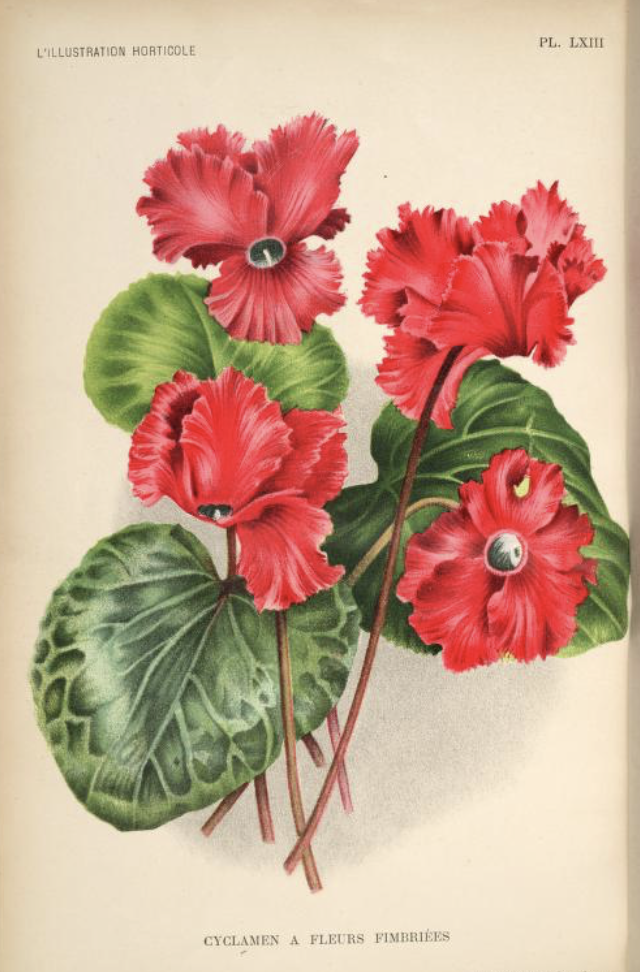

Of course that wasn’t true. Work continued in England, France and Germany and more variants and differences began to appear. Low’s Nursery of Clapton introduced some double forms, and others with crested or ruffled flowers which were not always that popular. The Belgian magazine which featured a plate of one of them said “C’est une monstruosité, mais une monstruosité décorative“. [It’s a monstrosity but a decorative one!] These were followed by the first variants with fringed flowers, before in 1900 St George’s Nursery Hanwell introduced a strain with not only fringed flowers but fringed leaves too.

The salmon colour introduced by Suttons was also used to cross with what were then the deepest pinks and purples available and I’d guess to most nurserymen’s surprise one colour variant that appeared was a true flaming red, which first was marketed in 1908. Another new variant had marginal colouring, usually in white , while others had striped flowers and yet more produced beautiful marked foliage on less straggly plants.

Throughout all this breeding one characteristic was generally neglected: the scent. Attempts to restore it were generally not very successful and even today most modern strains are almost completely scentless although a glance at the latest catalogues suggests that breeders it is there again in some strains but apparently it is a difficult characteristic to maintain while public demand isn’t yet great enough. Mass production of cyclamen began in the 1920s with Pierre Morel’s in southern France being the most prominent breeder.

Next steps included going the other way with plant and flower size. One regular reader has been in touch to tell me about the work done by Allan Jackson at Wye College, Kent, in the 1960’s while she was a student. He focused on breeding smaller scented plants by crossing large flowered varieties with wild forms and produced a range known as ‘Wye College Hybrids’ which had elongated flowers and attractively marked foliage. They were named after butterflies and were a very popular gift for students to take home at Christmas as they were far superior to those generally available at that time. Apparently they were still being marketed in 2021. [There’s more information about them in Gay Nightingale’s book Growing Cyclamen] Jackson was obviously ahead of the game because much smaller and mini-cyclamen became very fashionable in the 1970s, much easier to transport.and F1 hybrids also began to be created. This was important because they could be fairly guaranteed to come into flower at the same time and so could go consistently to flower auctions and garden centres en masse.

Although Pierre Morel’s nursery is still exists it is, like many other famous nursery companies, part of a conglomerate and export seeds to 40 countries while their genetics reach 70 countries. Other major European producers are Syngenta Flowers ; Schoneveld Breeding (Netherlands):Beekenkamp Group and Dummen Orange I’ve listed them because their on-line catalogues are worth checking out to see how far the poor cyclamen can be pushed and pulled!

Commercial cyclamen growing is big business although its obviously not in the same league as orchids or poinsettia. Unfortunately accurate up-to-date data is difficult to obtain, but the reports I’ve tracked down suggest its growing at a rapid rate 6-8% a year with most growth in the Asian market particularly in China India and Japan India, that is now the biggest market with over 35% of global trade. Of course in many parts of there world, including especially Asia C.persicum can be grown outdoors and used either as a permanent feature or as a bedding plant. So perhaps its not surprisng that Syngenta has a specialist company and catalogue for the region

Commercial cyclamen growing is big business although its obviously not in the same league as orchids or poinsettia. Unfortunately accurate up-to-date data is difficult to obtain, but the reports I’ve tracked down suggest its growing at a rapid rate 6-8% a year with most growth in the Asian market particularly in China India and Japan India, that is now the biggest market with over 35% of global trade. Of course in many parts of there world, including especially Asia C.persicum can be grown outdoors and used either as a permanent feature or as a bedding plant. So perhaps its not surprisng that Syngenta has a specialist company and catalogue for the region

If you’re having problems keeping your cyclamen alive remember that daytime temperature should not exceed 20° C. [so turn the central heating down!] and when yhe flowers and leaves begin to die back in spring, reduce the watering and let the tubers dry out. Keep them dormant in a cool dry place until early autumn, when [if you are lucky!] they will start to grow again of their own volition , then start watering again and with a bit more luck they’ll produce flowers for next Christmas.

If you’re having problems keeping your cyclamen alive remember that daytime temperature should not exceed 20° C. [so turn the central heating down!] and when yhe flowers and leaves begin to die back in spring, reduce the watering and let the tubers dry out. Keep them dormant in a cool dry place until early autumn, when [if you are lucky!] they will start to grow again of their own volition , then start watering again and with a bit more luck they’ll produce flowers for next Christmas.

However I confess even though I’ve written about them I don’t particularly like C.persicum – too plasticky and fussy for my liking – so please don’t give me one because I much prefer the wild forms of C.hederifolium and C. coum which flourish with in my garden with zero assistance!

You must be logged in to post a comment.