What do you know about Queen Charlotte?

What do you know about Queen Charlotte?

I’d bet for many people whatever they know comes from having seen her on Bridgerton, so they’re likely to know she was the wife of George III a marriage which lasted for over 57 years. They might also know that she had 15 children with him, and that there is some unfounded controversy about her ethnicity.

But I wonder how many might know that she was an enthusiastic botanist and very keen gardener ….& that she was not responsible for the fake -and anachronistic – wisteria seen in the series on the front of the Bridgerton residence .

Wisteria on Rangers House, Blackheath, the TV location of the Bridgeton residence. Wisteria was not introduced to Britain until 1816 , just a year or so before Charlotte died.

For more on wisteria see this earlier post

Most of the images in this post come from the Royal Collection Trust and are © His Majesty King Charles III, 2022. Links are provided to the relevant webpage for more information.

Sophia Charlotte was born into the ruling family of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, a minor independent duchy in northern Germany. When George III succeeded to the throne in 1760 his mother, Princess Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, [who developed the royal gardens at Kew] and his advisors were eager to have him settled in marriage. Of course it couldn’t be a Catholic princess and power politics ruled out many of the Protestant ones. However George was also King of Hanover and his German possessions had good relations with Mecklenburg so when the shortlist of potential brides was drawn up Charlotte was at the top. She was said to be “amiable” but not very well educated so would make a suitable, unthreatening match.

Her brother had succeed to the ducal throne in 1752 and moved the family seat to the palace of Neustrelitz, and it was there that Charlotte had spent her teenage years. Perhaps the gardens there helped develop her interest in plants. An English visitor left an account of them in 1768: As you’d expect they’re formal gardens and an orangery near the palace with parkland and avenues beyond with the usual collection of groves and alleys, and a variety of labyrinths, and statues, a curious grotto of shellwork, and at the end a lake with a village nestling on its further bank and beyond that a vast forest.

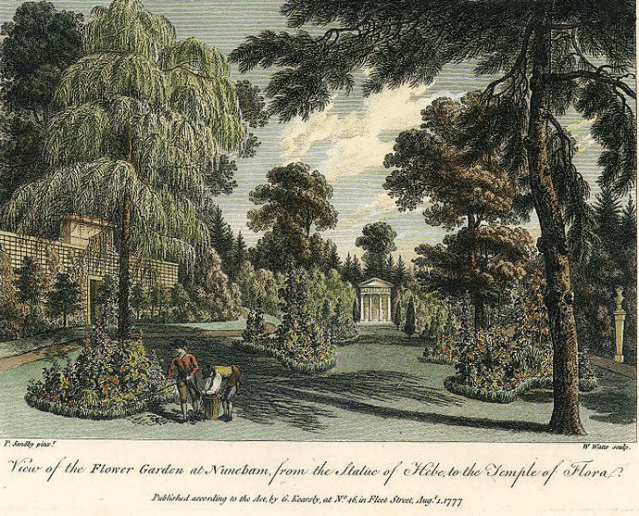

In 1761 Earl Harcourt the owner of Nuneham Courtney, who was later to become a friend and garden advisor to the new queen, was sent over to Mecklenburg to escort Charlotte to England. The marriage took place less than six hours after her arrival in London and her first meeting with George that September, and just a fortnight before the coronation. Despite the obvious haste it seems to have been an extremely happy match partly because it’s already clear that she took no interest in politics or government matters – indeed that was one of the reasons she had been chosen – but she shared many interests with George such as music, architecture, books, ceramics, furniture and gardening.

Nevertheless recent research shows the extent to which Charlotte acted independently of the king in these shared interests. She was among the most scientifically-minded of British queens and surrounded herself with intellectuals and practical people including the botanists Joseph Banks, Daniel Solander and John Lightfoot, the geologist Jean Andre de Luc, the novelist Fanny Burney, as well as Elizabeth, Countess Harcourt and Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Portland, women who were, like Charlotte, enthusiastic naturalists.

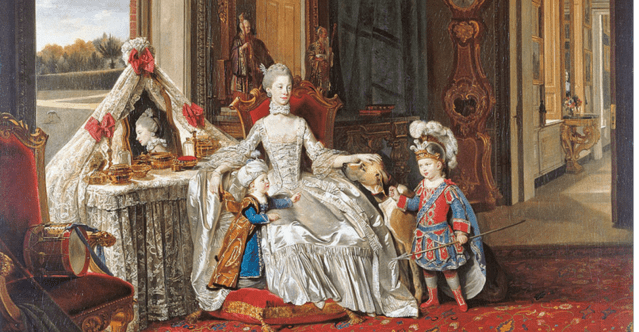

The Queen’s own interests focused on botany, cataloguing and drawing the remarkable plants and flowers that were grown in the gardens at Kew although unfortunately little of her own artwork survives. She was a patron of Zoffany, Gainsborough and Beechey as well Johann Christian Bach. She was also the dedicatee of Charles Burney’s History of Music 1776, of Josiah Wedgwood’s range of Queen’s Ware, and of Robert Thornton’s Temple of Flora.

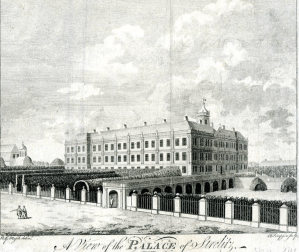

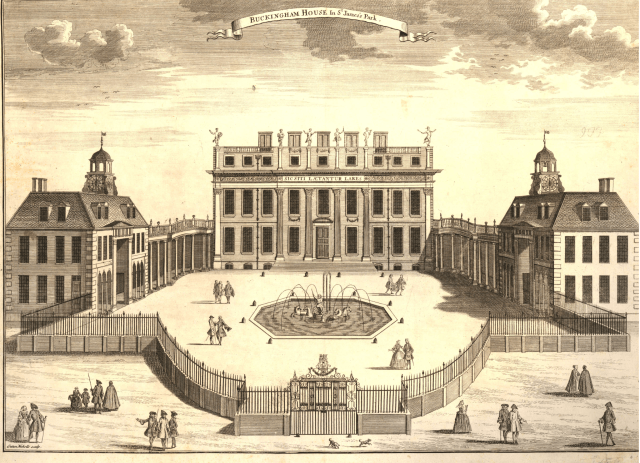

One of the first gifts from George to Charlotte was Buckingham House at the end of St James’ Park which he bought for £28,000 as her dower home rather than giving her Somerset House, the traditional residence of queen consorts. It soon became known as the Queen’s House although George quickly came to prefer it as his own London home as well, instead of the official court residence of St James’s Palace.

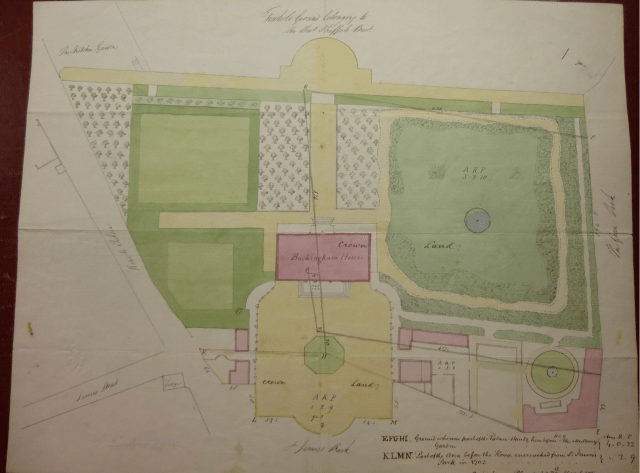

The house, much smaller than today’s Buckingham Palace, had been built in 1705 for the 1st Duke of Buckingham and the garden remained the grand but extremely formal one laid out by Henry Wise, with a long rectangular canal and wilderness. Her interest in gardening and botany was clear from the moment of her arrival in the country. It was reported for example that in that first summer she ‘took the air every evening, and through the day was at her own house in the Park’. Olwen Hedley, her biographer, writes rather romantically that “it is easy to picture the King and Queen wandering arm in arm down the Duke of Buckingham’s broad walk, which led from the west front through lime groves to the terrace at the end of the garden. The terrace overlooked a miniature park with a central vista of a canal flanked by double rows of limes, and at its north-west extremity sank into a wall covered with roses and jasmine, purposely left low to admit the view of a meadow full of cattle.”

Things began to change very quickly. What Roy Strong describes as “the stately approach” a huge courtyard and a central fountain and ironwork screens by Jean Tijou disappeared and between 1762 and 1776 the building was remodelled by William Chambers, the royal architect and the grounds were apparently also given a complete makeover almost certainly by Capability Brown who was revolutionising the approach to garden design.

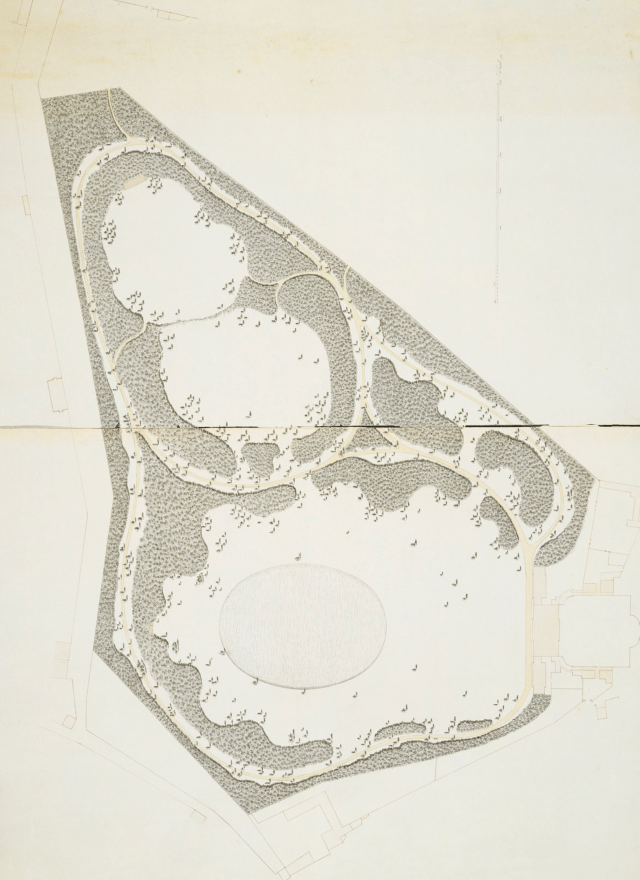

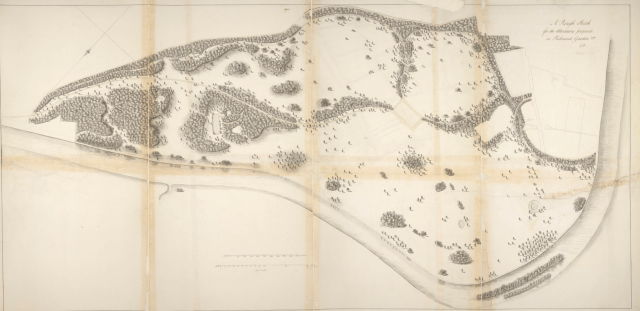

Two design schemes, probably by him survive in the Royal Library although Roy Strong wonders if perhaps they were by perhaps by Thomas Wright the astronomer/architect instead.

Charlotte established a flower garden and took evident pride in growing fashionable carnations and she had a Garden Tent made to provide shade by the royal upholsterer Mrs Naish. [Click here for more on this interesting character who had taken over her father’s role as ‘Royal Joyner and Chair maker’”]

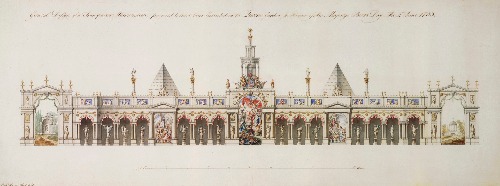

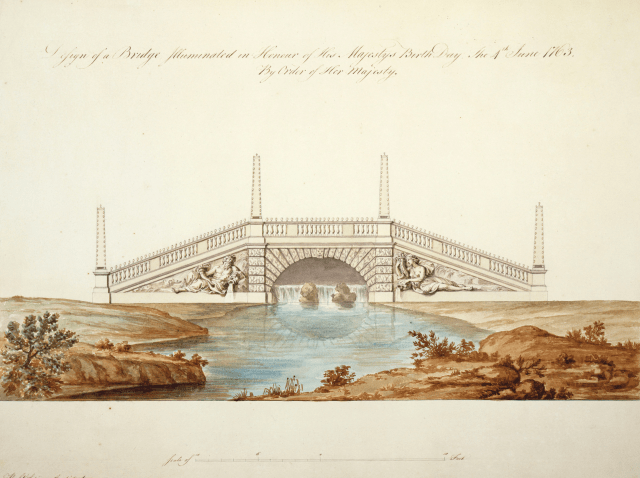

Two years later in 1763 Charlotte gave the king a surprise party in the palace gardens to mark his 25th birthday and the end of the Seven Years War. In addition to a concert and the grand supper that might have been expected, there were fireworks and an enormous illuminated “transparency” designed by Robert Adam probably based on those he had seen used in firework festivals when he was in Rome in the 1750s.

Transparencies were light-weight wooden structures covered with material such as linen, calico or thick oiled paper on which a design was painted and then lit from behind in the manner of stained glass. It was a favourite form of 18th century public art and could be seen in pleasure grounds such as Vauxhall but also on occasions of national rejoicing such as Royal weddings, births or military victories when they were placed in parks or on a smaller scale even in shop windows as part of the general “illuminations” (for more on this see Georgian Illuminations on the Sir John Soane Museum website).

Design for the fireworks

The whole thing was a surprise, with the Queen arranging that the carpenters and painters should get the whole structure ready while the king was away.

When he returned to Buckingham House it was after dark and the shutters were thrown to reveal the transparency lit up by 4,000 glass lamps.

The central scene depicted the King giving peace to every part of the globe (the terms of peace with France arranged at the close of 1762 were not finally proclaimed until March 1763) and trampling underfoot the hostile figures of Envy, Malice and Detraction. It was according to architectural historian David Watkins the perfect expression of optimism political and cultural at the start of the reign” [The Architect King p.]

Capability Brown moves centre stage on the royal garden scene very soon afterwards. He was appointed Chief or Master Gardener at Hampton Court in 1763 and two years later put in charge of St James’s Park as well. Little happened at Hampton Court because after the death of George II in 1760 the royal family never resided there again and it became merely grace and favour residences. Instead attention shifted to Kew where George and Charlotte had Richmond Lodge on the other side of Love Lane from his mother, Princess Augusta and where, when at Kew, the couple lived with their children until 1771.

The royal couple now turned him loose on the gardens there which had been largely created by George II’s wife Queen Caroline. Brown swept almost of it away including the farmland which had been one of its most distinctive features and turning it into a park with woodland and no garden buildings to speak of. This was to lead to much criticism of Brown by William Chambers and William Mason who attacked the ‘untutored Brown’ as a ‘peasant’ who had emerged from a ‘melon-ground’ and had levelled the ‘wonders’ created by ‘good Queen Caroline’. George and Charlotte seem not to have taken sides and even asked Chambers to design a new royal palace in their garden.

[For more on Caroline’s garden see these earlier posts:Queen Caroline & Merlin’s Cave and Queen Caroline & her Hermitage]

At the same time Chambers was also busy adding buildings in Princess Augusta’s garden. Charlotte’s brother, the Duke had been given a copy of Chambers’ Plans, elevations, sections, and perspective views of the gardens and buildings at Kew, in Surry, and now Charlotte followed that gift up by sending him a plan of the gardens. According to Ray Desmond, the historian of Kew, copies of several buildings, including the mosque were soon built in princely German garden.

The couple moved from Richmond Lodge to Princess Augusta’s White House at Kew in 1772 after her death, so plans for Chambers new palace were abandoned. Now in possession of both royal estates at Kew Charlotte and George merged the two gardens but perhaps surprisingly they didn’t ask Brown to remodel the other half and indeed it was said that nothing gave the Queen greater pleasure than “beautifying and enriching” what had been her mother-in-law’s section.

It may well be that she was following the advice of Lord Bute who had been George III’s tutor, and who served as prime minister from 1760-63. He had been a friend and advisor to Augusta especially about her gardens at Kew, and now seems to have played a similar role for Charlotte

The following year, 1773, her interest in plants was recognised when Strelitzia reginae – the Bird of Paradise – or sometimes The Queen Plant – was introduced from the Cape of Good Hope and named “as a just tribute of respect to the botanical zeal and knowledge of the present Queen of Great Britain” by Sir Joseph Banks, unofficial director of the garden.

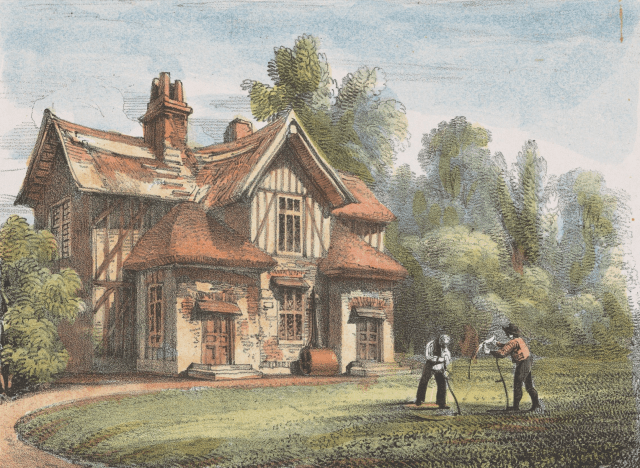

Charlotte then indulged another of her interests. George II’s wife, Queen Caroline, had kept a menagerie at Richmond but a map of 1771 shows a “new menagerie” in a clearing in the woods at the furthest corner away from the White House. There was a ring of pheasant enclosures with a keeper’s cottage which stood at one end of a 3 acre paddock. By 1772 the keeper’s lodge had a second floor and it seems clear that the royal family were already using it as a summerhouse for picnics and shelter. It was to become the core of wha t is now known as Queen Charlotte’s Cottage.

Charlotte then indulged another of her interests. George II’s wife, Queen Caroline, had kept a menagerie at Richmond but a map of 1771 shows a “new menagerie” in a clearing in the woods at the furthest corner away from the White House. There was a ring of pheasant enclosures with a keeper’s cottage which stood at one end of a 3 acre paddock. By 1772 the keeper’s lodge had a second floor and it seems clear that the royal family were already using it as a summerhouse for picnics and shelter. It was to become the core of wha t is now known as Queen Charlotte’s Cottage.

The London Magazine for 1774 described “The queen’s cottage in the Shade of the garden” as “a pretty retreat: the furniture is all English prints of elegance and humour. The design is said to be her majesty’s.” A good example of a Cottage Ornee built of red brick with what Ray Desmond describes as Tudor pretensions. The main room upstairs with its floral patterns was probably decorated by Charlotte’s third daughter Princess Elizabeth.

The Queen had started her menagerie a few months after her marriage with the gift of a female mountain zebra that was brought from the Cape by Sir Thomas Adams, the captain of HMS Terpsichore unfortunately it became an excuse for satire at the new queen’s expense and a symbol of political rivalry and corruption as well as starting what Christopher Plumb in his account calls “a flurry of sexual innuendo”, about Her Majesty’s Ass. [It’s a really interesting story but there’s no room for it here, but you can read all about in his very entertaining book on The Georgian Menagerie.] Other creatures followed all sorts of exotic cattle, colourful birds, a pair of black swans, buffaloes, a quagga and most notably the first kangaroos in Europe.

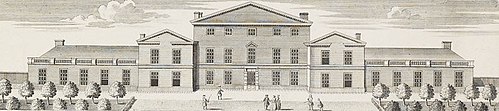

The Queen’s Lodge on the right

In 1775, Charlotte acquired yet another home, this time at Windsor. Known as Queen Anne’s Cottage it was given to her by George and renamed the Queen’s Lodge William Chambers did some remodelling and added castellations with Charlotte writing: “The King is building it but I am paying for the furniture and I settle my accounts the moment they are delivered. Besides that, I am in treaty with a gentleman to buy a garden and house adjoining mine for which I must pay £4000.” It became the couple’s home while the alterations were taking place in the main castle.

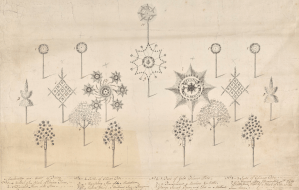

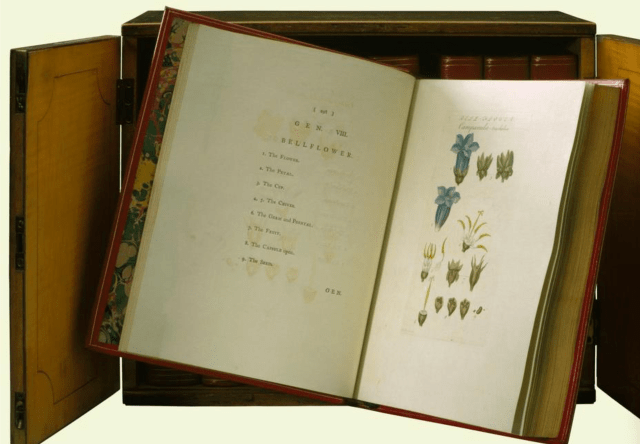

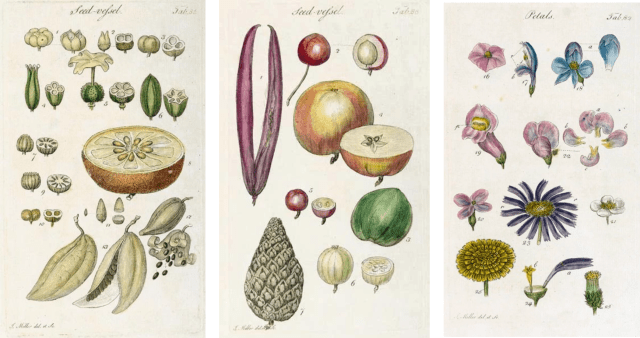

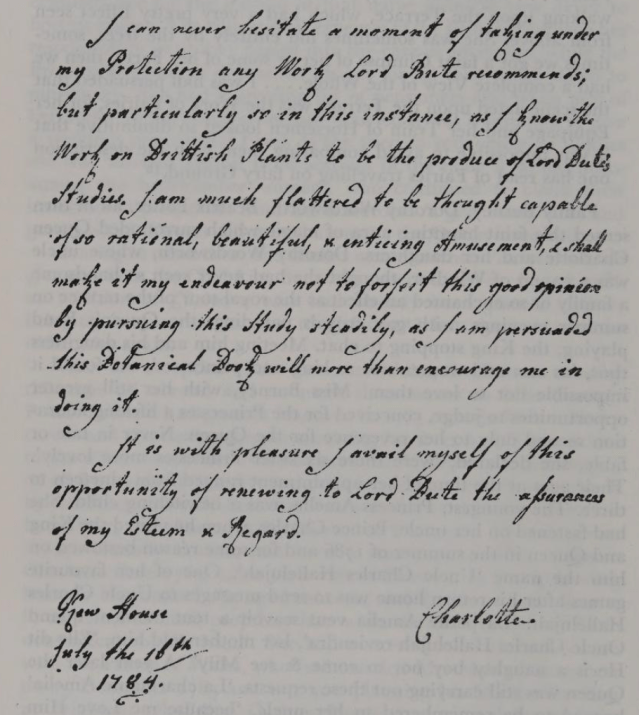

Her continuing friendship with Lord Bute meant that she was one of the 12 recipients of Lord Bute’s 9 volume re-classification of plants: Botanical Tables which had taken him well over 20 years to compile. Started by 1761 at the latest, a dozen or so copies were finally printed in 1784 and presented to the great and the good, including Catherine the Great of Russia, the Duchess of Portland, Sir Jospeh Banks, and Comte de Buffon of the Jardin Royale inn Paris.

Bute dedicated the work to Charlotte and this marked a milestone in the Queen’s patronage of botanical studies and at the same time signalled her unequivocal support for botany as a subject suitable for feminine study. His dedication described the work as ‘composed solely for the Amusement of the Fair Sex under the Protection of your Royal Name’.

As you can see from her reply [below] the Queen was ‘much flattered to be thought capable of so rational, beautiful, & enticing Amusement, & shall make it my endeavour not to forfeit this good opinion by pursuing this Study steadily, as I am persuaded this Botanical Book will more than encourage me in doing it’.

As you can see from her reply [below] the Queen was ‘much flattered to be thought capable of so rational, beautiful, & enticing Amusement, & shall make it my endeavour not to forfeit this good opinion by pursuing this Study steadily, as I am persuaded this Botanical Book will more than encourage me in doing it’.

There is more information about Bute’s Botanical Tables on the website of the National Museum of Wales which is where the images below can be found.

In fact she hardly needed any encouragement to pursue her study of plants, which had occupied her consistently at Buckingham House, Kew and then at Windsor where the presence of Mary Delany , her friend, neighbour and fellow botanist, must have provided a further incentive for this work. Later in the 1790s Charlotte’s gardening and ‘Botanising’ came to be focussed around Frogmore [of which more next week] where she assembled the major part of her botanical library, including Bute’s Botanical Tables.

Four years later in 1788 Charlotte offered Bute a present in return. This was “the beginning of an Herbal from Impressions on Black Paper” presumably in the style of her friend Mary Delany. Helped by Kew’s head gardener William Aiton, and Princess Elizabeth she told Bute she hoped to take further specimens ‘quite in the Botanical way’. However she needed practical help because as she she explained “The Specimens of Plants being rather large it requires more Strength than my Arms will afford, but in the Smaller kinds I constantly assist ..”

1788 was also year the Austrian artist Franz Bauer was appointed Botanical Painter to the Royal Gardens at Kew’ and it wasn’t long before he was giving the queen and her daughters drawing lessons and supervising their “colouring in” of some of his engravings. Princess Elizabeth who acted as the Queen’s unofficial secretary wrote to a friend ‘We are all at present busy in learning Botany… what we are in most need of are magnifying glasses, Mama wants a very strong little one I want one with three magnifiers which by the learned I understand is the best’.

All this was to be put to good use in Charlotte’s next, and most significant, venture, creating a garden at Frogmore, of which more next week.

A fascinating read thank you