We’re all used to having snowdrop open days early in the year but I wonder why there don’t seem to be any open days for crocus -which is a bit odd since crocus are more colourful and cheerful, and don’t blend in with snow or frost, and while they naturalise easily they’re not very demanding. Any way, that sent me thinking…and after I’d done a bit of research I also wondered how and why such a little flower could have such a big history.

As E.A.Bowles the great gardener and garden writer said in the opening lines of his book on the family: “The Genus Crocus deserves more attention than it has hitherto received in British gardens.” So here goes…

As I’m sure most people will know the most important crocus, in economic terms at least, is Saffron – Crocus sativus. It was already well known in the ancient world and was probably introduced to Britain by the Romans for use in dyeing.

It appears regularly in medieval and early modern herbals and by the 14thc was being grown as a commercial crop – hence Saffron Walden in Essex and Saffron Hill in London – with Thomas Bullein a Tudor physician claiming in A newe booke entituled the gouernement of healthe published in 1558 that ‘Our English Honey and Saffron is better than any that cometh from any strange or foreign land.’

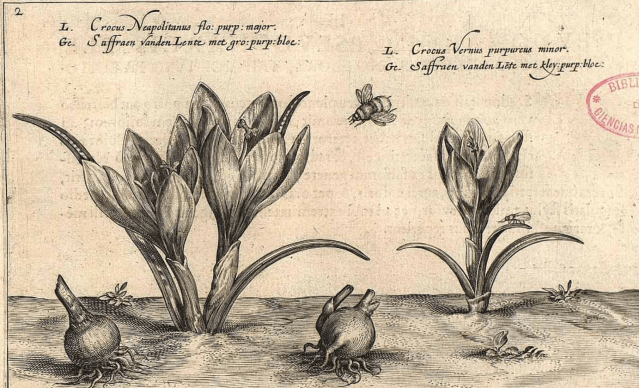

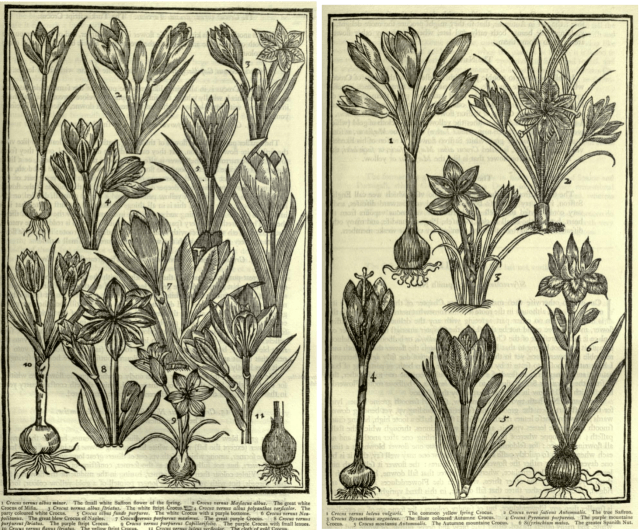

By the time John Gerard published his Herbal in 1597 he includes seven “sundry sorts” including both spring and autumn flowering crocus, Wild Saffron, and Meadow Saffron, some of which he had obtained through the good offices of Carolus Clusius of the Leiden Botanic Garden.

It’s almost certain that the common European crocus, C.vernus, was introduced by monks and grown in monastic gardens in Britain, perhaps as a cheap substitute for saffron. Richard Mabey discusses this at length in his book Flora Britannica in response to a little snippet in Gardeners Chronicle in 1872 about one particular water meadow near Nottingham. This was “enlivened with thousands of its purple blossoms” and apparently “hundreds of young men and maidens, old men and children, may be seen from the Midland Railway picking the flowers for the ornamentation of their homes. Any stranger fond of flowers who visited Nottingham now for the first time would feel surprised to see the large handfuls of Crocuses in the windows of the poorer and middle-class inhabitants….

Crocuses in mugs, in jugs, in saucers, in broken teapots, plates, dishes, cups-in short, in almost every domestic utensil capable of holding a little fresh water; and very beautiful they look, even amid these incongruities, still they look far fresher when seen nestling amongst the fresh green herbage of these oft-inundated meads.”

Not unsurprisingly when Mabey went to visit the scene in 1974 there were almost no crocus to be seen. However the meadow in question was once the property of the Benedictine Priory of Lenton, a daughter house of Cluny in Burgundy where the crocus grows wild freely and Mabey notes that there are more surviving local populations associated with other sites linked to Lenton.

Non-European crocus first appear across Western Europe around the mid-16th century, when, like tulips, they were bought back from the Ottoman Empire by the Holy Roman Emperor’s ambassador to the Sublime Porte, Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq. Some of those reached Clusius at Leiden and then spread into elite gardens where they attracted the attention of flower painters.

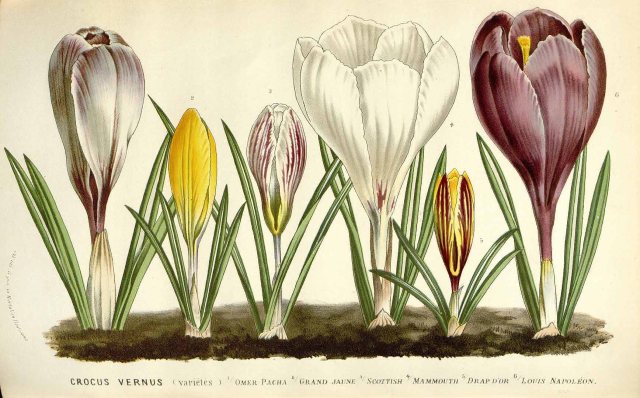

By 1620, new garden varieties had been developed, and featured in contemporary illustrations, such as that of Crispin van de Passe in his Hortus floridus of 1614. There are even a few accounts of special crocus gardens in the seventeenth century, such as the Saffron Garth of Walter Stonehouse at Darfield, Yorkshire. where there was a crocus border 170ft long. John Parkinson is, as usual more detailed describing. as many as 27 spring flowering sorts and 4 autumn flowering ones, including the “true saffron”.

Crocus were soon also being forced or at least grown indoors, Batty Langley for example in his New Principles of Gardening of 1728 recommends planting a clump of snowdrops in a pot and surrounding it with crocus and this “will, in the January following, make a glorious Appearance, and grace their Places of Abode, wherein they then are placed”. He also has a lengthy account of saffron and how best to cultivate it.

Crocus are included too in Robert Furber’s Twelve Months of Flowers (1730) and the follow-up The Flower Garden Display’d .(1734) Both include not only several crocus in the plate for February but also a yellow colchicum in the September group, and Saffron in October. Additionally The Flower Garden Display’d has a whole chapter on The Art of raising Flowers without Trouble; to blow in full Perfection in the Depth of Winter, in a Bedchamber, Closet, or Dining-Room.” It was supposedly written by someone named Sir Thomas More Bart. [according to Catherine Horwood in her Potted History p.49] this is likely to have been a botanist named More since there was no knight of that name at the time] and again it includes suggestions for crocus and snowdrops being used as house plants for winter display.

More wrote: “I had several Crocus’s ‘that gave me their Bloom with full Strength in little China Tea-pots I ranged, close to the Glass in my Chamber Window: I gave them Air sometimes in the middle of the Day, by opening the Window for half an Hour, when the Wind was not in the North or East, and when the Weather was not frosty.” They bloomed he said around Twelfth Night.

More also suggested growing crocus like several other bulbs in a glass with just water. A layer of cork with a hole cut for the roots was floated on top. The corms were set “so that the Bottoms of the Bulbous Roots would but just touch the Water, of which I take the Thames Water to be the best, as being strongly impregnated with prolific Matter, like rich Earthwell manurd for Corn or Garden Uses….The whole Process of that Germination (if I may so call it) was visible through the Glass.” They too flowered successfully.

More also suggested growing crocus like several other bulbs in a glass with just water. A layer of cork with a hole cut for the roots was floated on top. The corms were set “so that the Bottoms of the Bulbous Roots would but just touch the Water, of which I take the Thames Water to be the best, as being strongly impregnated with prolific Matter, like rich Earthwell manurd for Corn or Garden Uses….The whole Process of that Germination (if I may so call it) was visible through the Glass.” They too flowered successfully.

It was shortly after that that Linnaeus formally described the Crocus genus in Species Plantarum in 1753, broadly sub-dividing them into spring and autumn sorts, although of course taxonomy is never as simple as we non-taxonomists would like.

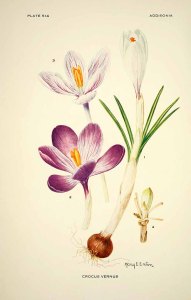

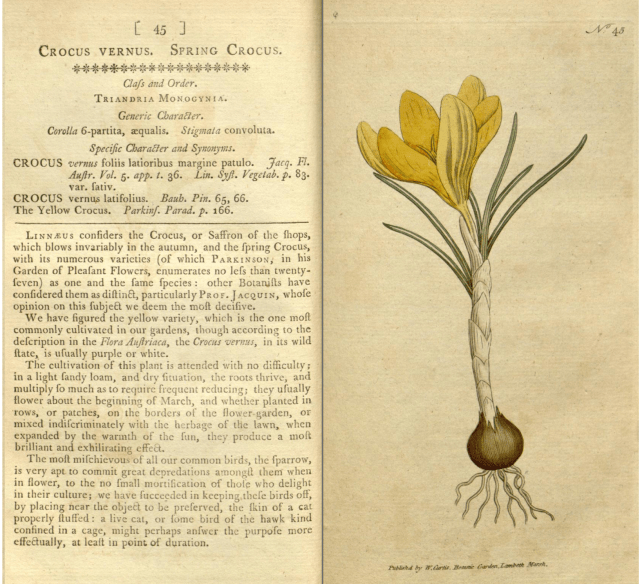

After that the scientific study of the genus was slow. The common yellow Crocus vernus appeared in the first volume of William Curtis’s Botanical Magazine in 1787 . There is however little botanical information to accompany the illustration but the reader is advised how to best protect crocus from attacks by sparrows by placing “near the object to be preserved, the skin of a cat properly stuffed”.

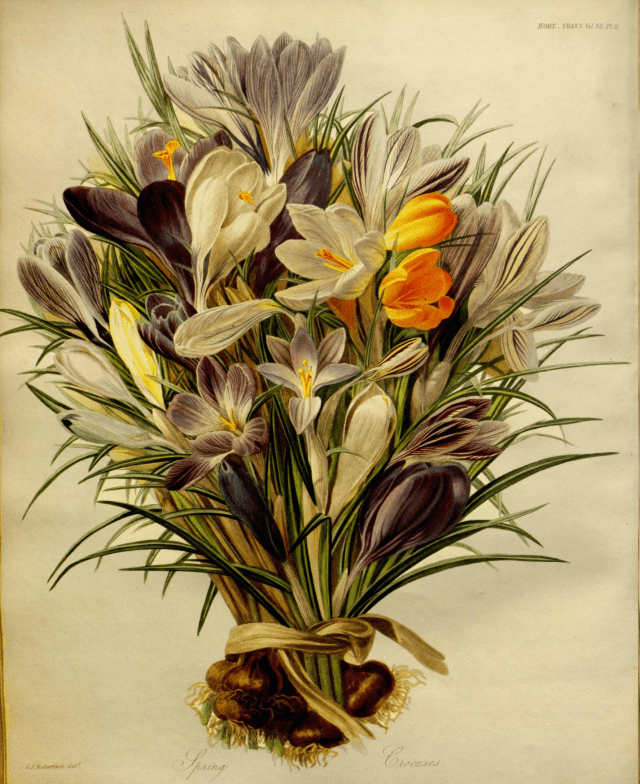

Things have changed noticeably by the time the next image appears in the 1803 volume of the magazine. Then a whole page is given over to some basic history and detailed references. But the real break through comes in 1809 when Adrian Hardy Haworth, a scholarly amateur botanist wrote a short paper for Horticultural Society published in their Transactions in 1820. He makes no claim to investigate their history, merely to list the species he knows and describe the best ways of cultivating them. However in passing he reveals how widespread. they were being grown in Britain. Crocus were he says “universally admired, annually gilding with vegetable blue and gold, the borders of almost every garden while innumerable forced pots of Crocuses are seen annually exposed to sale in Covent Garden, along with other vernal flowers.”

Josiah Wedgwood encouraged the popularity of growing bulbs indoors in attractive containers which reached its peak around the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries. He even created a special post referred to as ‘porcoipins for snowdrips’ in an account of wares fired at the factory. These proved very popular and remained in production for almost 200 years. A quick google search will also show you much they’ve been copied.

They are more usually as Haworth says “called a Hedgehog…made in the shape of that quadruped, but full of holes, and filled with earth; and one large Crocus root is placed internally, in the front of every hole; the bristling leaves of which, shooting through the holes, represent grotesquely enough, but not unaptly, the spines of the animal…. I have also flowered the larger bulbs of Crocuses in glasses of water, after the manner of Hyacinths: but in this way they produce only a scanty bloom.”

If you’re interested in the idea of unusual crocus pots then you might like to have a look at the those on the Kennemerend website

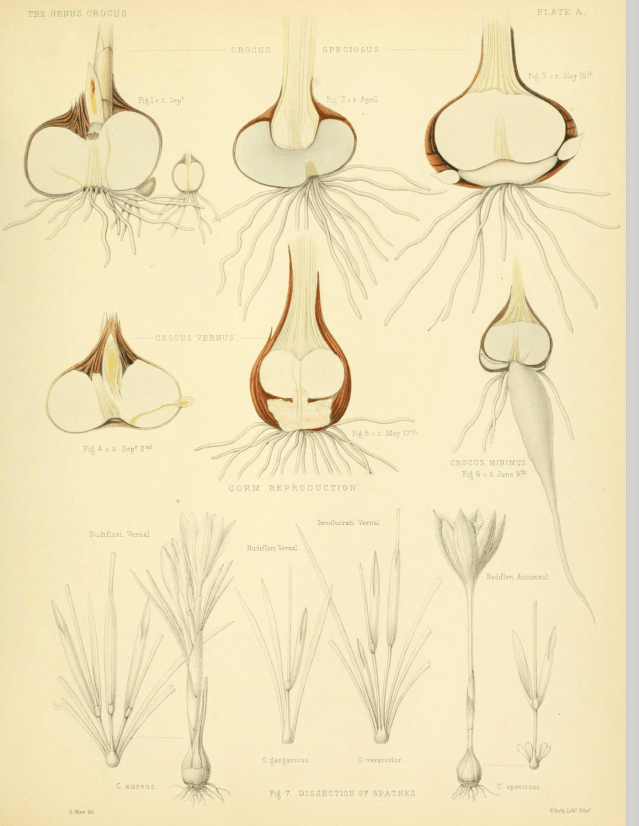

from Transactions 1830

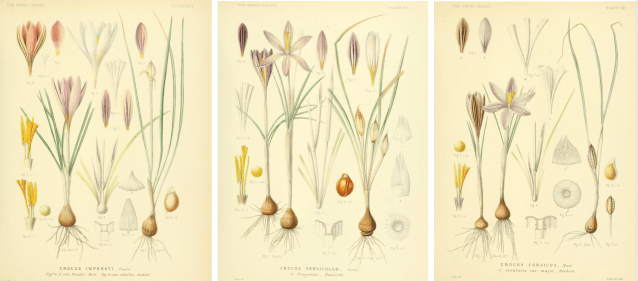

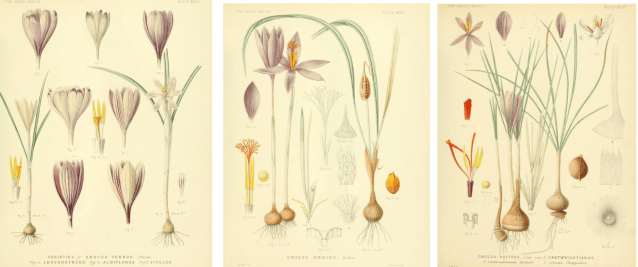

from Maw’s A monograph of the genus Crocus

Ten years later the Transactions published another paper this time by Joseph Sabine, the Secretary of the Society. It is much more detailed and shows how botanists and horticulturists were beginning to take a more serious interest in crocus. He offered a comprehensive list of recent and historical papers by continental authors and also mentions several collectors in Britain. Sabine himself had been interested in crocus for about 30 years and had given the Horticultural Society a collection for its gardens at Kensington in 1818 which he “had obtained from various quarters, many from Holland, several from seed, others from the public Nurseries and private Gardens in the neighbourhood of London”.

The next to investigate crocus was William Herbert, Dean of Manchester, who did it even more thoroughly, based on his own experiments with the hybridisation, although unfortunately he did not include any illustrations. An expert on bulbs [see this earlier post] in the 1847 Journal of the Horticultural Society he listed the 43 species he identified, clearly explaining where the seed or corm had come from, and in the process showing the extensive networks that existed between botanists not just in Britain but across Europe, and which often called on diplomats to help gather and return them to Britain.

While there was more complex taxonomic discussion over the next few decades it’s not until 1886 that the first major study was published by George Maw. Maw was another supposed amateur. In his other life he was the owner of a successful tile making business. However he was an extremely diligent botanist and gardener writing a heavyweight but beautifully illustrated A monograph of the genus Crocus in the best traditions of Victorian botany which underlies the modern understanding of the genus, that took him eight years to write.

It involved extensive travel in the southern and eastern Mediterranean regions some with Henry Elwes, another well-known bulb collector. (If you’ve heard of him it’s probably because of the snowdrop Galanthus elwesii)

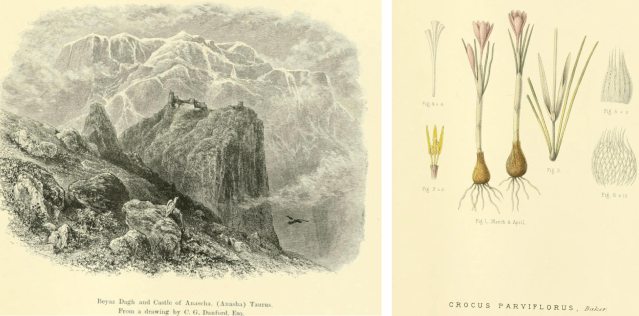

Crocus parviflorus and his Taurtus Mountains homeland from A monograph of the genus Crocus

The book has not only beautiful illustrations of the flowers but also engravings of some of the regions whence they came. The list off those who helped him on these travels is extensive and shows the reach of Imperial diplomacy because in addition to foreign dignitaries it includes Her Majesty’s consuls and Vice-Consuls across the region. He grew many of the species at his home Benthall Hall in Shropshire where the National Trust have a project to restore some of his work.

And latest news – no sooner had I posted this than the March issue of The English Garden dropped through my letter box [crazy as it was only 24th of January!] with an article about Crocus and George Maw, and his work at Benthall.

What Maw revealed – or rather a notice announcing the publication of Maw’s book in Gardeners Chronicle in 1887 revealed- is that there was a crocus-growing industry in Britain at the time, although it was limited to a small area of south-east Lincolnshire around Spalding. It was on land which had been reclaimed from the Wash and had “a rich alluvial deposit admirably suited for the growth of every description of bulb or tuber.”

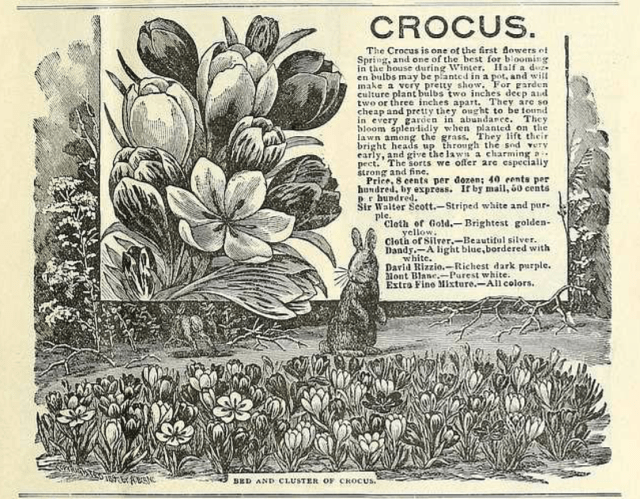

The notice also included lengthy comments by a Mr Barrell of Spalding who explained that “The yellow Dutch Crocus is the variety most esteemed for profit; although large quantities of the white and blue varieties (of C. vernus), such as David Rizzio, Prince Albert, Queen Victoria, and Walter Scott, are grown.” [These were all still being listed in the 1920s but seem to been superseded & I can’t find any colour images of any of them]

The corms “which are too small for sale, and range from the size of a Pea to that of a very small wood-nut)” were used as the equivalent of seeds and sown in drills about 10 inches apart in November; and in this soil and climate the very smallest corms will bloom, consequently, as they are usually grown in plots of from a rood to an acre in extent, a field of yellow Dutch Crocus, under a bright sun, when in full bloom is a most gorgeous sight.”

“The third year after planting they are taken up in June and are sorted; the large bulbs being sent to market, and the smaller ones replanted as seed. …The increase, during the time the bulbs are growing from seed into saleable bulbs, is almost in-credible; amounting probably to 500 per cent. in number, and 2000 per cent. in weight.”

From Barrell’s account we can guess the sale and value of the industry because “*From fifteen to twenty millions of Crocuses are, perhaps, annually sold; the price for what are usually denominated in seedsmen’s catalogues, ‘first sized bulbs,’ averages from 5s. 6d. to 6s. per thousand, whilst second and third sizes realise from half to two-thirds that sum. The trade is usually carried on through the medium of “dealers,” who purchase the bulbs from cottagers and small farmers, and in their turn dispose of them in bulk to the large seedsmen in London and other places.”

And then comes a little giveaway about advertising. The Netherlands has long had a reputation for the quality of its bulbs and British nurseries bought substantial numbers for sale, making a point of the fact the stock they were offering was Dutch. Barrell adds that: “It is not too much to say that at least nine-tenths of the Dutch bulbs which are advertised annually as “Just imported from Holland,” are from Holland in Lincolnshire, and are guiltless of any connection with Holland on the mainland of the continent of Europe.”

Interestingly Maw asked by Gardener’s Chronicle for his opinion of Barrell’ s figures and he was quite dismissive, saying they were “excessive “and that had said “his experience in growing Crocuses is that in ordinary garden culture they do not increase in such a ratio. Nor did they have the value he imputed because “the price received by the growers scarcely exceeds l4d. per pound, or about the value of new Potatos.” He then adds that, maybe people should actually be eating the corms as they do in Syria and Asia Minor “because looking at their nutritious composition, more than half the weight consisting of sugar and starch, [so] their culture and use as an article of food may be worth consideration.”

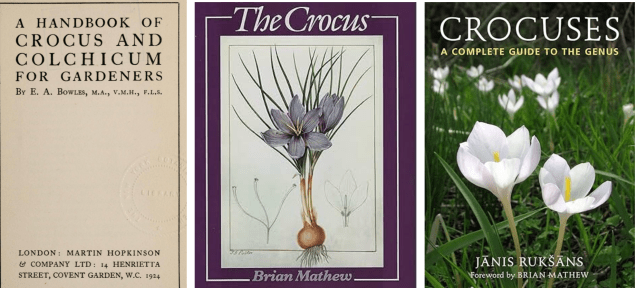

Since Maw’s day there have been three more major monographs on Crocus. However they’re all very much about taxonomy and identification & none of them has such by way of history. The first is the 1924 Handbook on Crocus and Colchicum by E.A.Bowles [who will be the subject of next week’s post], then in 1982 came Brian Mathew’s scientific and encyclopaedic volume The Crocus (1982). The latest which isn’t on-line and is a bit out of my price league is Jānis Rukšāns 2011 Crocuses: A Complete Guide to the Genus

For more information the Wikipedia page on crocus is a good place to start because its has lots of references and links, and for those who really want specialist knowledge have a look at the website of the Crocus Group of the Alpine Gardening. Society.

You must be logged in to post a comment.