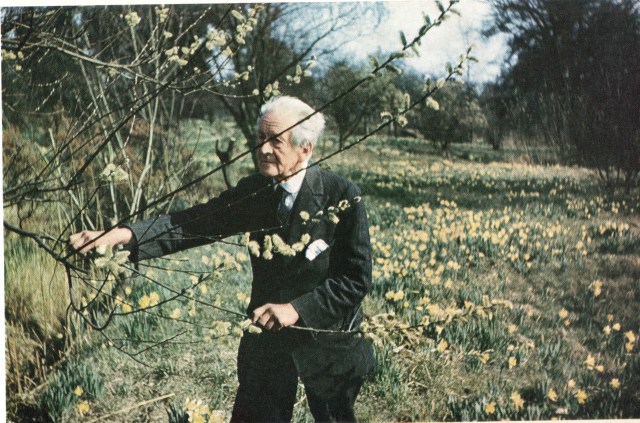

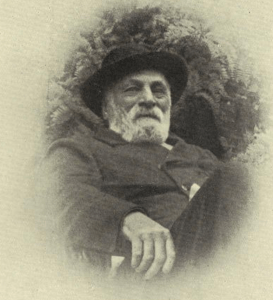

Following on from last week’s history of the crocus this week’s going to look at the man who really popularised them in Britain. Edward Augustus Bowles -“Gussie” or “Bowlesy” to his friends – was one of the 20th century’s great gardeners. Largely self-taught he was an accomplished artist, entomologist and botanist and an entertaining and knowledgeable writer who travelled widely with many eminent plant hunters of the day including his good friend, the plant hunter Reginald Farrer, who called him both “Little Father Augustus” and “The Crocus King”.

Following on from last week’s history of the crocus this week’s going to look at the man who really popularised them in Britain. Edward Augustus Bowles -“Gussie” or “Bowlesy” to his friends – was one of the 20th century’s great gardeners. Largely self-taught he was an accomplished artist, entomologist and botanist and an entertaining and knowledgeable writer who travelled widely with many eminent plant hunters of the day including his good friend, the plant hunter Reginald Farrer, who called him both “Little Father Augustus” and “The Crocus King”.

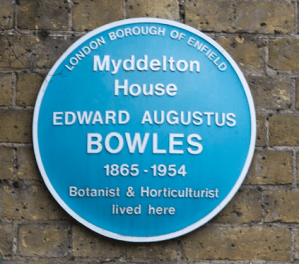

Apart from the remarkable garden he created at Myddelton House, his life-long home on the outskirts of Enfield, and the many cultivars he raised, Bowles became a stalwart of the Royal Horticultural Society volunteering for them for over 50 years. He also authored several books which are still highly readable.

A grey and drizzly day in January probably isn’t the best time to see a garden but I hope the photos encourage you to go and visit Myddelton as soon as you can.

As usual the images my own unless otherwise acknowledged

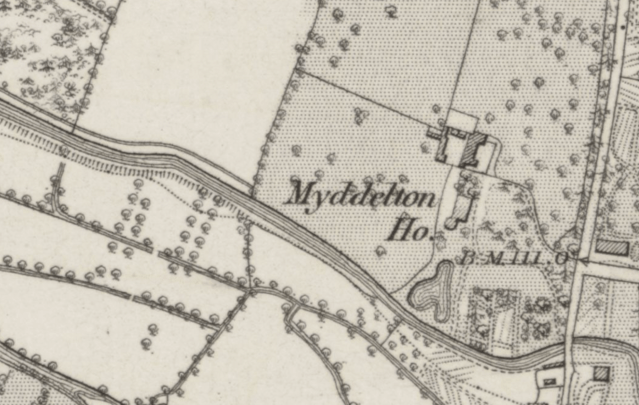

Myddelton House stood next to the New River, a canal built in the early years of the 17thc to supply fresh water to London, which was owned by “The Governor and Company of the New River”. It was an incredible feat of engineering for its day –a continuous wood lined channel 10ft wide by 4ft deep, dug out by hand, following the 100ft contour line for 39 miles.

In 1684 the wealthy Garnault family who had fled France as Huguenot refugees purchased a controlling interest in the company and in 1720 paid £215 for Bowling Green House, a Tudor building, that stood in the grounds of the long vanished royal palace of Elsing, and on a loop of the New River. The estate passed by marriage to the Bowles family in 1809. They soon demolished the old house and commissioned a new fashionable mansion naming it in honour of Sir Hugh Myddelton who had been driving force behind the construction of the canal.

It was there that Bowles was born on 14 May 1865. His father Henry was the last Governor before the company was taken over by the Metropolitan Board of Works in 1904. Gussie was educated at home because he had lost the sight in his right eye at age of eight and thought ‘too delicate for public school’, although his parents also encouraged him to take up outdoor pursuits such as entomology, ornithology and landscape painting. They also encouraged an interest in gardening by giving him his own small patch of garden, where apparently crocus grew. He took up all of these hobbies with enthusiasm and continued to enjoy them for the rest of his life. One other present may have had an effect on his future way of looking at plants – this was the gift from his grandmother of Edward Lear’s Nonsense Botany. [If you don’t know anything about it then read this earlier post.]

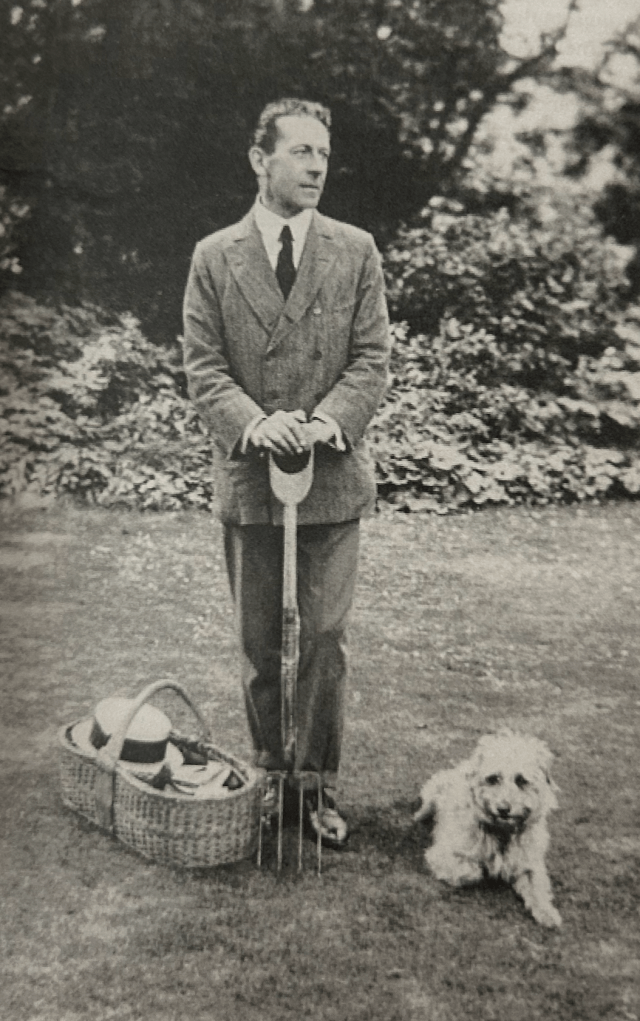

Bowles in 1910

He went up to Cambridge with plans to become a clergyman but this idea was abandoned when two of his siblings died and instead he returned home to be a support to his parents. Nevertheless he remained profoundly religious, teaching in the local Sunday school, and becoming a lay reader and churchwarden at the nearby Forty Hill church. His father was involved in many local philanthropic projects which in his turn Gussie continued to support for the rest of his life. In particular he ran a Night School for local underprivileged boys who became known as Bowles Boys, with the gardens at Myddelton House becoming a haven where they helped with garden tasks and played cricket on the lawns.

A family friend was the garden writer Canon Henry Ellacombe who encouraged Gussie’s interest in horticulture. Later Bowles remembered him as “the foremost both in time and ability of my teachers in garden-craft”. With Ellacombe’s encouragement he took charge of his father’s garden where gravelly soil and low rainfall limited the range of plants he could introduce, but which lent itself wonderfully to bulbs and alpines.

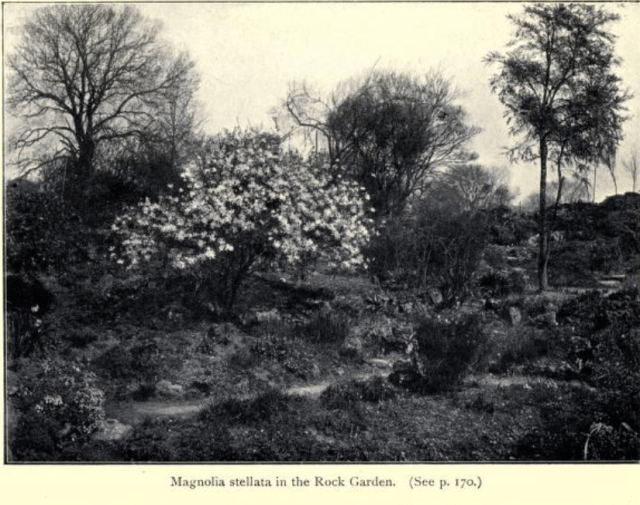

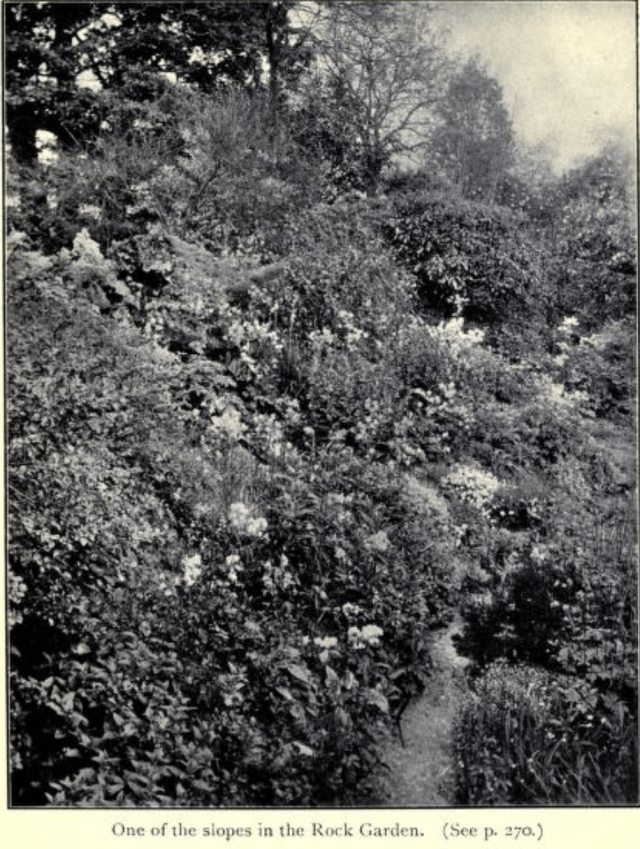

In 1889 Bowles made his first trip abroad, to Italy, with his brother Henry and sister-in-law Dolly and following it he began to develop the garden of Myddelton House with a rock garden with alpine plants. If this conjures up the sort of suburban heap of builders rubble covered with a bit of soil – you’ll need to rethink completely!

Reginald Farrer later described the rock garden as “a lowly piece of ground, wandering here and there in gentle natural ravines and slopes. No vast structure, but bank added to bank as the plants require it, and nothing asked of the structure except that it be simple and harmonious, and best calculated to serve the need of the little people it is to accommodate—to accommodate, and not be shown off by. For here the plants are lords, and the rocks take their dim place in the back-ground…. Let the lovers of display go home abashed before a display such as not a hundred bedded out Aubrietias can give …” Bowles himself wrote a long review of books about Rock gardening and alpine plants for the RHS Journal in 1916.

Bowles [second from right] with friends on a plant hunting expedition in the Pyrenees. Image scanned from Mea Allan’s biography

Gussie’s first unusual crocus was bought in 1891 and, entered into his garden record book as ‘Crocus speciosus transylvanicus‘ but he was soon also collecting crocuses in the wild – unforgivable today but of course perfectly acceptable then. One example was C. nudiflorus which he found so plentiful near Bayonne that everywhere he dug for other plants he found small corms of it in the soil. It was “a very handsome and hardy plant but not often seen in gardens and seldom offered by nurserymen”. More, often longer trips followed – Malta, Egypt, Italy, and Greece and North Africa, – and regularly to the Alps in June in an effort to escape hay fever and in the company of Reginald Farrer, the rock garden enthusiast. And of course he was also visiting gardens all over Britain. Wherever he went, he took his paintbox with him and some of his exquisite watercolours of flowers and a few of his landscapes can be seen in public collections although most were given to friends and are now mostly in private hands.

Encouraged by Ellacombe Bowles had joined the Royal Horticultural Society in 1897 and purchased life membership for £26. A real bargain for both sides as he was to serve on 15 committees and be a council member for 36 years. In 1916 the society awarded him its highest honour, the Victoria Medal of Honour, before, in 1926, making him a Vice-President, a position he held until his death in 1954.

Soon the garden at Myddelton was attracting the attention of the gardening press, the first I can find is in 1895 with a short account for The Garden by F.W.Meyer, the Exeter based landscape designer. But the two best accounts come later. A page-long laudatory piece by Rev. Joseph Jacob came out in The Garden in June 1909 on ‘Myddelton House: its Garden and its Gardener’. Jacob commented on Bowles “wide botanical knowledge and his love of “rarities” and “forms” and “proper sorts of monstrosities…”

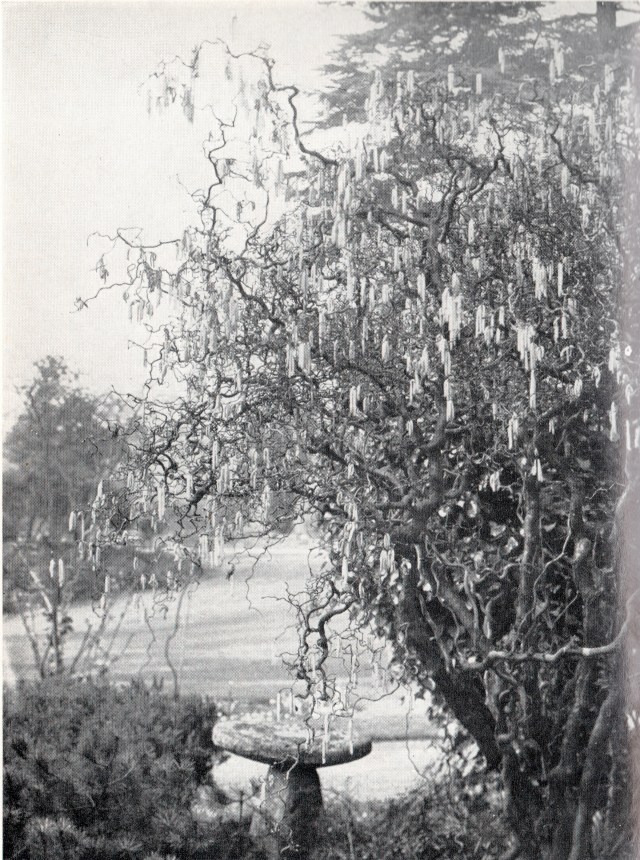

The corkscrew hazel. Image scanned from Mea Allen’s biography of Bowles

The reference to monstrosities is probably a recognition of a part of the garden that later became known as The Lunatic Asylum which began when he cleared away a tired Victorian shrubbery. In its place he planted a Magnolia lennei which became, what Mea Allen his biographer called the ‘keeper’ of the Lunatic Asylum. The next “inmate” was a twisted hazel given him by Canon Ellacombe, and it wasn’t long before friends and acquaintances began sending cuttings of their own ‘demented’ plants for his collection.

Jacob goes on to describe other features including things one might not have expected – (well which I certainly didn’t expect) – for example …

..” alongside the New River…is a wide, circular terrace with a row of round beds filled in the spring with Darwin Tulips and Miss Willmott’s deep blue Forget-me-nots, and later on with such as scarlet Geraniums. It is the one place in the whole garden where some concession is made to the mid-Victorian craze.”

That tradition is still maintained

Jacob also reported the “outdoor collections of succulents, varieties of flat-stemmed puntias, Cereuses and Echinocactuses made in 1899 and still flourishing, kept alive with the help of large glass lights, which are put over them to throw off the winter rains and then entirely removed.”

Jacob also reported the “outdoor collections of succulents, varieties of flat-stemmed puntias, Cereuses and Echinocactuses made in 1899 and still flourishing, kept alive with the help of large glass lights, which are put over them to throw off the winter rains and then entirely removed.”

Every summer they were put out on the terrace overlooking the pond He called it “a sort of Brighton or Eastbourne for them during their summer outing”.

The conservatory was also full of them- and still is as are the restored glasshouses.

He ended his visit to Bowles’ library adding a “more or less complete list of what Mr. Bowles himself calls his proudest treasures:” – all 15 of them. But unsurprisingly at the top are “(l) The large collection of Crocus species and hybrids; (2) his Snowdrop forms” before some unexpected choices: a couple of sorts of asparagus, dwarf Almonds and Gunnera.

Bowles and then iris border in the kitchen garden – image from an information board

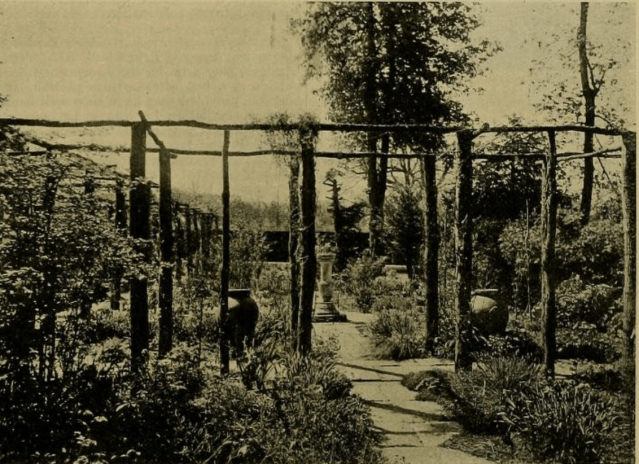

The replacement rustic pergola

The following year, 1910, two more magazines visited. The Gardeners Magazine carried a long article by George Gordon who described “the spacious grounds, …containing noble trees, handsome shrubs, roses in groups and running riot over a rustic pergola, closely shaven lawns, and other objects that at once appeal to all who appreciate the charms of a well-furnished garden” and of course much more.

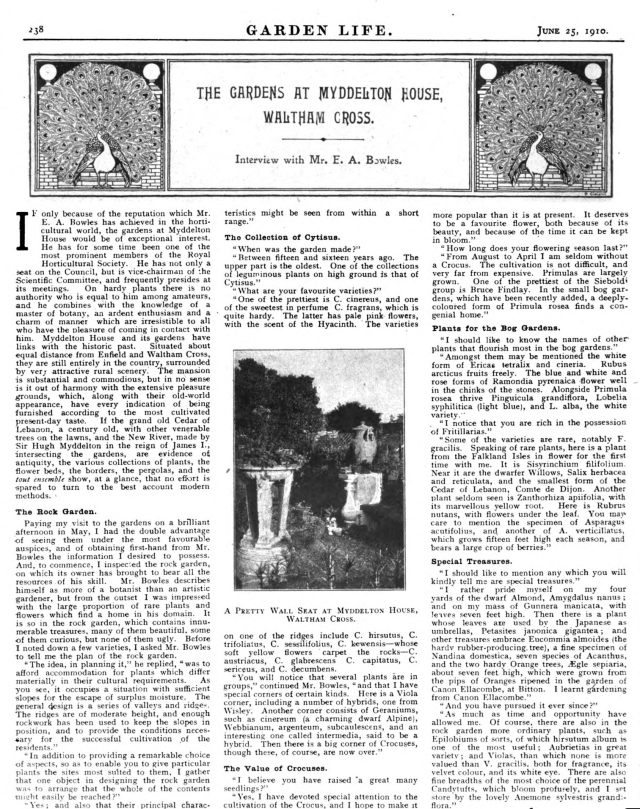

However the best piece I’ve discovered was published in June that year in the little known magazine Garden Life. It took the form of an interview with Bowles and I’ve included the first page in its entirety. The rest of the article can be found in full here

Bowles admiring the rose-covered market cross. Image from one of information boards

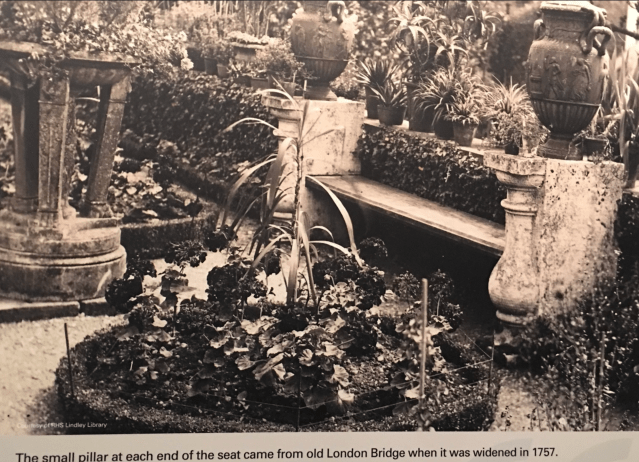

Bowles clearly had something of a magpie nature and not just with plants. The garden also contained lots of architectural fragments and curiosities.

The most obvious are the surviving elements of Enfield’s Market Cross which was about to be demolished in 1904 when Bowles rescued it.

There are bits of old London Bridge too, and some stone paving slabs from a street in Clerkenwell lifted when the New River was being constructed.

There are also a pair of 6 feet high lead ostriches by John Van Nost c1720, which came from a neighbouring property, although these had to be removed indoors to protect them.

There are also a pair of 6 feet high lead ostriches by John Van Nost c1720, which came from a neighbouring property, although these had to be removed indoors to protect them.

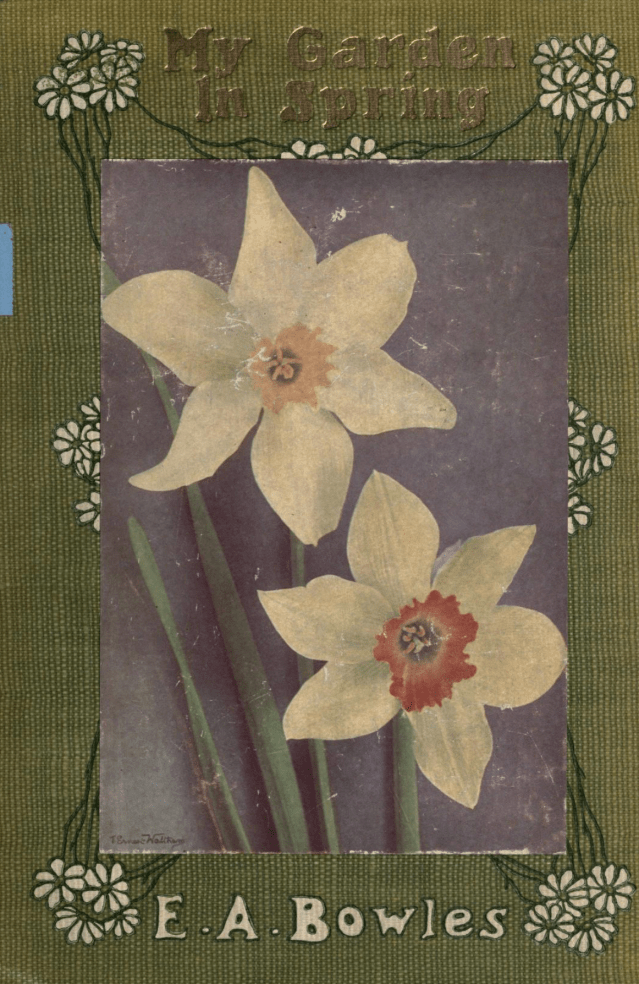

In December 1912 Hooper Pearson, editor of the Gardener’s Chronicle, suggested that Bowles write a series of books describing his garden season by season. In the end he wrote three My Garden in Spring (1914), My Garden in Summer (1914), and My Garden in Autumn and Winter (1915) which were all republished in the 1990s. His friend Reginald Farrer wrote that they showed ‘how a gentleman can wear his garb of knowledge with a gay air and humour, dignified yet easy, and whimsical and personal’.

Gussie’s method was deceptively simple. He walked round the garden and wrote as if he was chatting to a visitor in person about the plants as they went. He could do this because he knew his garden inside out and so his knowledge was profound. Nor did he pontificate but dropped amusing anecdotes into his writing to make it more easily understood.

One of the crocus frames today

Farrer had conjured up the name Crocus King ‘Rex Crocorum’ for Gussie in 1911 and The Garden’s reviewer thought “he writes with such enthusiasm on crocuses that he hopes to induce others to follow in his footsteps, as he no doubt will.” There’s no doubt that that’s precisely what happened.

The family of crocus caught his eye early on his trips abroad, and became his first passion, well before they were grown more widely. In particular he would have seen Crocus vernus — the Alpine meadow species that has formed the basis for many large-flowered hybrids but he preferred the smaller earlier flowering species, and by 1901, Myddelton House had an area set aside with “frames and pots containing almost all the known Crocus species that can be grown in Britain.

In all some 135 named species and varieties. It was then just a small step to hybridising them and he raised and named 14 sorts from crosses of C. chrysanthus and C. biflorus naming them after birds although as is usually the way many of these have not lasted commercially.

He began writing about crocuses too, with the first article about his own new cultivar crocus C. niveus ‘Bowles’ which was he thought ‘far and away the most beautiful of all white-flowered autumnal species’. He was to carry on writing about them for the rest of his life because as he said in My Garden in Spring his “heart glowed more for a crocus than for the most expensive Orchid.” [There’s a full list of all his articles in the further reading at the bottom of the post.]

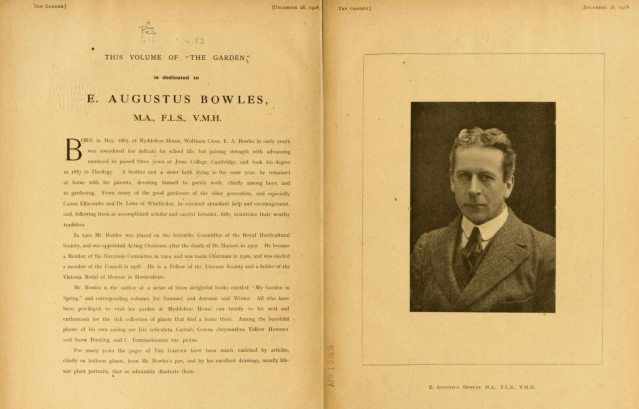

William Robinson dedicated the 1918 volume of The Garden to Bowles because for many years the magazine had “been much enriched by articles, chiefly on bulbous plants, from Mr. Bowles’s pen, and by his excellent drawings, usually life-size plant portraits, that so admirably illustrate them.”

William Robinson dedicated the 1918 volume of The Garden to Bowles because for many years the magazine had “been much enriched by articles, chiefly on bulbous plants, from Mr. Bowles’s pen, and by his excellent drawings, usually life-size plant portraits, that so admirably illustrate them.”

Given his enthusiasm, indeed passion for crocus, surprisingly it then wasn’t until In 1924 that he wrote A Handbook of Crocus and Colchicum (2nd edn, 1952) which sadly is only illustrated in black and white. However crocus were far from his only love. He was also particularly fond of all the early flowering genera such as snowdrops, Narcissus, Tulips, and Anemone and A Handbook of Narcissus [not available online] followed in 1934.

Bowles in the Alpine Meadow. Image scanned from Mea Allen’s biography

Like many other labour-intensive gardens the garden at Myddelton House deteriorated during the two world wars and never completely recovered from them. In old age, Bowles’ vision deteriorated badly and he could no longer see plants properly but he could still identify many by smell and taste. It can’t have helped that he refused to install electricity in the house and relied entirely on oil lamps. Nor could he walk well, and his trips around the gardened to be taken in a wheelchair. Nevertheless he was still working. A companion volume on the Anemone family, in collaboration with William Stern was well underway when he died in 1954, but unfortunately never finished although his working notes are available to read in the Lindley Library.

His archive and some paintings were given to the RHS Lindley Library, others to the Natural History Museum, but to ensure his garden survived Bowles bequeathed them together with Myddelton House to the Royal Pharmaceutical Society and Royal Free Medical School, with a Gardens Advisory Committee, set up to oversee the maintenance. The kitchen gardens were converted to grow medicinal, poisonous and narcotic plants for teaching and research, notably cannabis and opium poppy, while some of the potting sheds became laboratories.

The path down to the Alpine Meadow whim is now closed off during the renovation work

Inevitably academia found the upkeep too much. Attempts to economise included the heart-breaking decision in 1968 to use some of the spoil from the construction of the Victoria line to fill in the section of the New River that ran through the grounds. So now there’s a sweep of lawn where for 350 years there had been flowing water.

Eventually the estate passed to the Lea Valley Regional Park Authority, who use the house as their HQ. The upside of this, however, has been the creation of detailed Conservation Management Plans [available on-line here] for renovation of the grounds which have been open to the public for free since 2011. Their restoration projects have recreated a working kitchen garden, renovated the glasshouses, replaced the pergola, with work now going on to restore the alpine meadow.

As Bowles entry in ODNB ends: “A country gentleman following no gainful occupation, he combined high intellectual and artistic gifts with an ever kind and generous disposition. His wide knowledge, unostentatiously shared, his generosity, his integral wisdom, and sense of humour made him many friends, young and old, throughout his life… His death thus broke the last links with the great amateur horticulturists of late Victorian times…”,

As Bowles entry in ODNB ends: “A country gentleman following no gainful occupation, he combined high intellectual and artistic gifts with an ever kind and generous disposition. His wide knowledge, unostentatiously shared, his generosity, his integral wisdom, and sense of humour made him many friends, young and old, throughout his life… His death thus broke the last links with the great amateur horticulturists of late Victorian times…”,

For further information you can’t do better as starting points than look at the website of the E.A.Bowles Society, and Myddelton House gardens pages of the Lea Valley Regional Park. For a longer read try Mea Allen’s biography, or The Crocus King by Brian Hewitt, former head gardener at Middleton. Click here for a full list of his writings.

He sounds like a fascinating guy!! Must visit Middleton House some time. Did he have anything to do with the Bowles Mauve erysimum, I wonder?