My partner dropped a subtle hint suggesting I should do something for the blog to celebrate Valentine’s Day. Of course it might just have been a subtle hint that I should do something for him too but it set me thinking….

My partner dropped a subtle hint suggesting I should do something for the blog to celebrate Valentine’s Day. Of course it might just have been a subtle hint that I should do something for him too but it set me thinking….

What on earth has St Valentine got to do with gardens?

Well obviously there are the slushy floral sentiments of the Victorians, and the cold commercialism of today’s overpriced and imported red roses but is there anything more interesting?

There’s precious little real evidence about the saint himself. That’s unsurprising since there ar e many candidates for the “real” St Valentine. The traditionally accepted main contender is probably an early Christian bishop who was executed on the Via Flaminia outside Rome on February 14, 269. It’s claimed that his head was later taken to the church of Santa Maria in Cosmedin in the centre of Rome, where it can still be seen. His feast day was eventually established by Pope Gelasius I more than 200 years later in 496 AD.

There’s precious little real evidence about the saint himself. That’s unsurprising since there ar e many candidates for the “real” St Valentine. The traditionally accepted main contender is probably an early Christian bishop who was executed on the Via Flaminia outside Rome on February 14, 269. It’s claimed that his head was later taken to the church of Santa Maria in Cosmedin in the centre of Rome, where it can still be seen. His feast day was eventually established by Pope Gelasius I more than 200 years later in 496 AD.

However the name Valentine and variations of it were common in the Roman and early Christian world and there are plenty of other contenders who appear in early martyrologies. They are all shadowy figures with little or no information about them, many of them locally inspired, or the subject of later invented stories. They come from all over Italy including three separate ones from Ravenna alone, as well as Poland, Spain, Holland, Germany, France and Palestine. There are even several bodies or just heads of the saint – including one given to Winchester Cathedral by Queen Emma in 1042. Effectively what has happened is that their stories, including the fictional ones, have been subsumed into the popular legend. During the reforms of the 1960s, the Roman Catholic Church, having found no evidence of his existence, dropped St Valentine’s Day from the official calendar but that has had no impact on his popularity.

What does appear clear is that the first linking of Valentine with “love” doesn’t come until Chaucer’s poem the Parliament of Fowls, probably written around 1382. So how and why did this happen? And does it take us any closer to gardens?

Before Chaucer the Western tradition had no real room for the expression of ‘love’ in its literature. To the mediaeval elite marriage was not an institution for love but for land and heirs, and because passion was forbidden by the Church, ‘love’ was simply a duty. However, the notion of idealized ‘love’ – which was described by contemporaries as “Fin Amour” – went against this utilitarian basis of marriage.

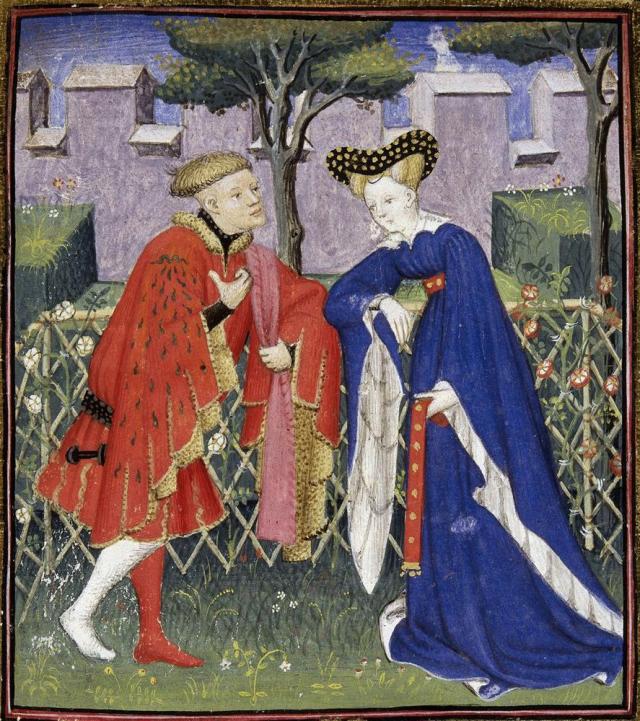

‘Fin amour‘ – refined love – is characterised by a series of stylised rituals between a knight and a high-ranking but married lady, where desire has to be tempered with decorum.The perfect knight was as gentle in his pursuit of love as he was valiant on the battlefield. He owed obedience and loyalty to his lord, despite the hardship and dangers and in the same way he must show faithful devotion and obedience to his lady, performing heroic deeds in an effort to win her favour.

Despite all this, typically the knight’s love is unrequited!

Literature, such as the famous Roman de la Rose, spells this out from the 12thc onwards, and by Chaucer’s day such sentiments were ingrained with poetry, manuscript illustrations and even tapestries showing gallant men courting and idealising women.The setting for such devotion is often a garden.

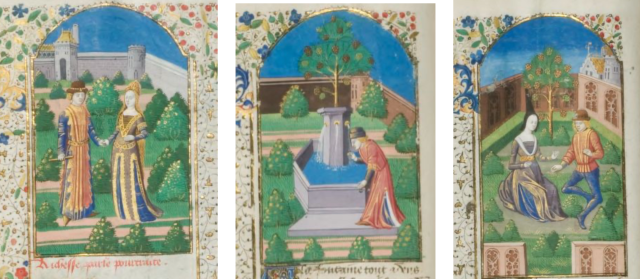

A garden plays a central role in the Roman de la Rose, a very long poem begun by Guillaume de Lorris around 1230 and continued by Jean de Meun approximately forty years later. With over 21,000 lines, it is probably the most influential non-religious literary work of the Middle Ages and survives in more than 130 different manuscript versions. These have all been digitised in a joint project of the Sheridan Libraries and the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The Roman de la Rose is the place where we can finally pin down a link between the idea of ‘love’ and the ‘rose’.

It is another complicated plot, full of allegories, narrated by a young man of 25 who has a dream. In it he discovers the walled Garden of Pleasure, where a beautiful woman personifying Idleness greets him at the gate. Inside he meets characters such as Diversion, Danger, Slander, and Fear as well as the more friendly Honesty, Pity, Beauty and Generosity. Seeing rose bushes he tries to pick a bloom for himself – the flower, of course, representing his ideal lady.

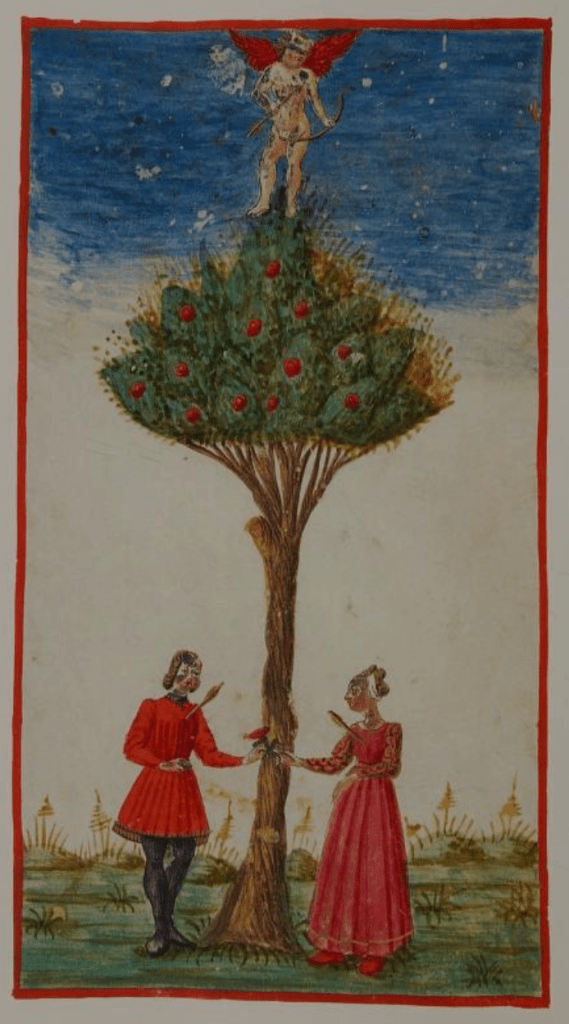

The God of Love shooting the Lover

Le Roman de la Rose. Bruges c.1490British Library, Harley MS 4425 f. 22

As he does so Cupid shoots him with several arrows, and leaves him hopelessly in love with the Rose. However, his efforts to obtain her meet with little success. When he steals a kiss, it alerts her keeper, Jealousy, and the defences of his castle where the lady is held are strengthened.

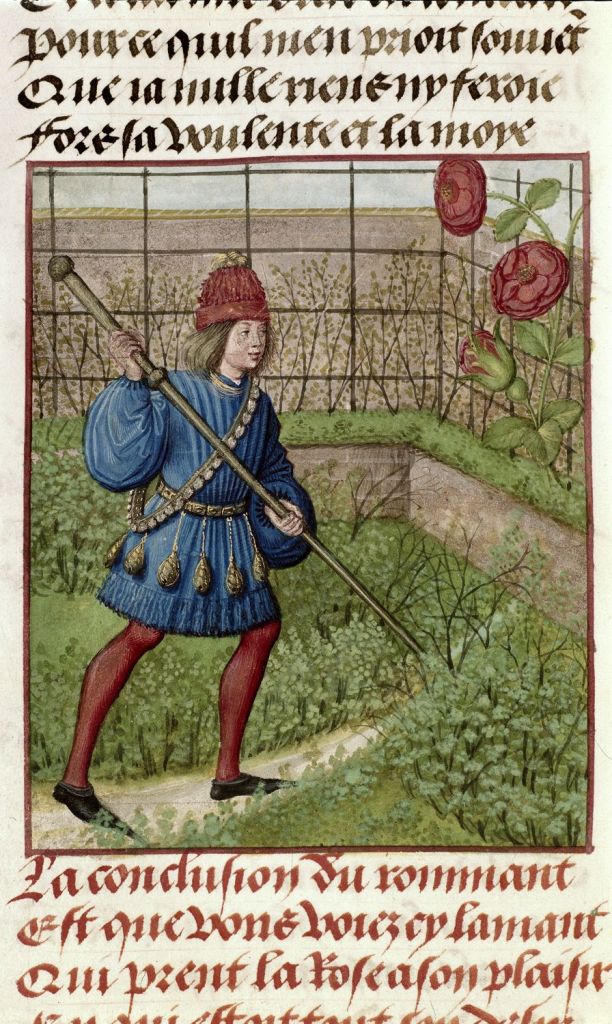

De Lorris’s section of the poem ends with the lover outside the castle lamenting his fate. The poem then changes style, with de Meun adding a rather bawdy account of the plucking of the Rose, a task achieved through deception, and a far cry from the idealized quest for love.

The poem was well known throughout Europe, and was translated by Chaucer as The Romaunt of the Rose. This was printed in 1532 on the direct orders of Henry VIII. Most of the surviving manuscript versions have illustrations and some of them, especially the later ones, give a little insight into the form and features of mediaeval elite gardens.

For more information, a detailed plot and analysis about the Roman de la Rose click here.

But how and where does Valentine come into the story of love – unrequited or otherwise?

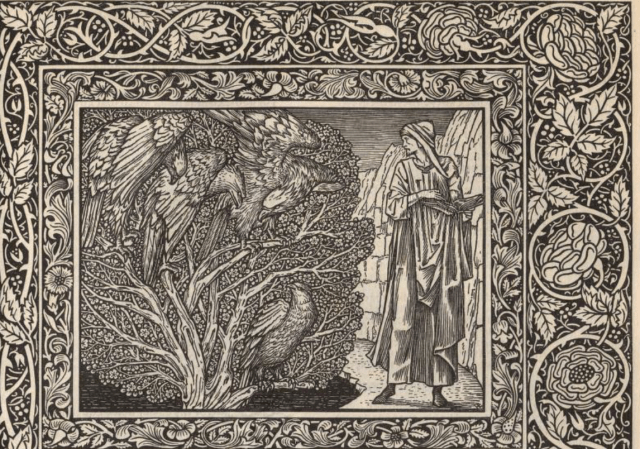

Chaucer used the same dream format when he wrote The Parliament of Fowls. His poem also has a convoluted plot, but just as in the Roman de la Rose, the narrator is guided through a garden “full of blossomy boughs” and where “every wholesome spice and herb grew”. There he “saw Cupid our lord forging and filing his arrows under a tree beside a spring, and his bow lay ready at his feet” before arriving at the temple of Venus. On the temple walls were “painted many stories” of doomed lovers including Dido, Pyramus and Thisbe, and Tristan and Isolde.

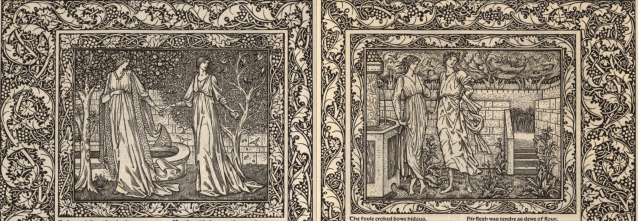

Cupid forging his arrows in the garden, and two of Venus’s attendants in the garden outside her temple by Burne Jones from William Morris’s Chaucer 1896

Chaucer’s narrator then “returned to the sweet and green garden [where] there sat a queen who was exceeding in fairness over every other creature… This noble goddess, Nature, was set upon a flowery hill in a verdant glade.”

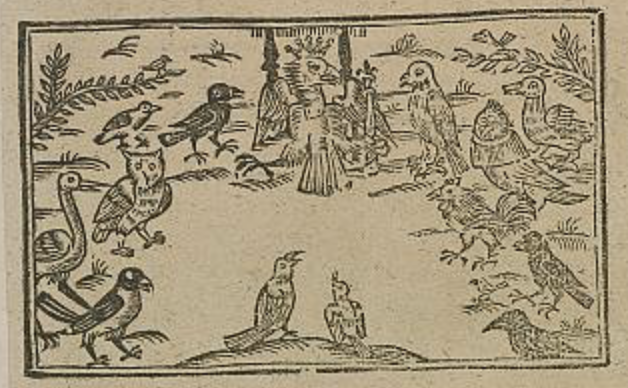

She was presiding over a Parliament of Birds, “for this was Saint Valentine’s day, when every bird of every kind that men can imagine comes to this place to choose his mate.”

Of course no writer on natural history, ancient or medieval, has ever suggested that birds actually meet on 14 February to choose their mates. Birds mating and nesting is more likely to happen around the end of April or beginning of May depending on the weather. Instead it’s likely this another example of the way that stories about the various Valentines have merged, because the feast day of St Valentine of Genoa, whom Chaucer would have know about, was on May 3rd.

Of course no writer on natural history, ancient or medieval, has ever suggested that birds actually meet on 14 February to choose their mates. Birds mating and nesting is more likely to happen around the end of April or beginning of May depending on the weather. Instead it’s likely this another example of the way that stories about the various Valentines have merged, because the feast day of St Valentine of Genoa, whom Chaucer would have know about, was on May 3rd.

The rest as they say is history … or rather myth.

There simply isn’t time/space here to go into the arguments about how and why this happened but for more on that as well as about the various Valentines and which was the “genuine” one see Henry Kelly’s detailed account in Chaucer and the Cult of Saint Valentine. (1986)

And myths there are aplenty. The most common one is that Valentine’s Day is a hangover from the Roman feast of Lupercalia which like other pagan festivals had been hijacked by the early Christian church, and becauseLupercalia had always been associated with romantic love the association transferred to Valentine. This was widely accepted by the late 18th century and indeed that story is still trotted out all the time via Mr Google but actually there is little evidence for it.

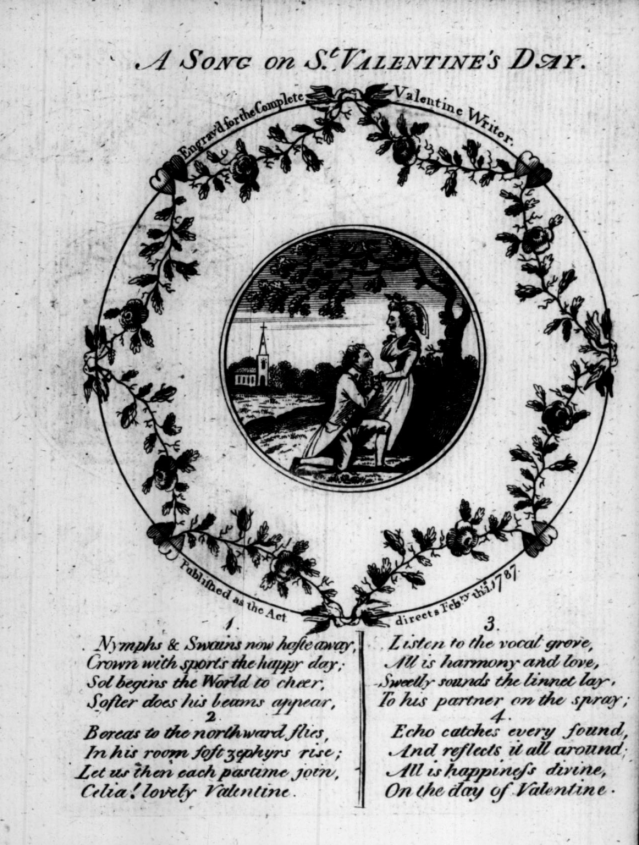

The more modern associations also started around the late 18thc with The New English Valentine Writer published in 1797 being the first of many books of trite and sentimental rhymes written for the occasion. Cards for Valentine’s Day are another early “tradition” established before Christmas cards and boosted by the introduction of the penny post in 1840 when cheap mass-produced cards began to appear.

Nowadays apparently over 1 billion cards are sent every year as Valentine’s Day has become another “Hallmark Holiday” along with Mother’s Day and Halloween.

However along the way to this commercial hype there was an interesting revival of interest in medievalism in the 19thc. It led writers and artists to revisit and rework the myths associated with Roman de la Rose and similar romantic stories. Edward Burne-Jones, for example, had read Chaucer’s Romaunt of the Rose when he was at Oxford, but in 1860 on one of his regular visits to the British Museum he saw and greatly admired a 15th century manuscript of Roman de la Rose.

A decade or so later he and William Morris collaborated on designs for a series of wall-hangings inspired by the poem. Morris designed the backgrounds whilst Burne-Jones drew the figures. Their designs were then embroidered over the course of 8 years by the wife and daughter of Sir Lowthian Bell the owner of Rounton Grange, Northallerton, Yorkshire where they were to be hung. Burne-Jones and Morris also designed a series of murals for the house based on the legend.

It also led to a separate trio of paintings which tell an abbreviated version of the story. The first is The Pilgrim at the Gate of Idleness in which the narrator/lover in the form of a pilgrim meets Idleness depicted as a beautiful woman who tries to entice him in. Having escaped her siren-like temptation, the Pilgrim is led by the god of Love through a thicket of wild roses which symbolizing the difficulties and dangers of his mission.

In the final painting, The Heart of the Rose, Love leads the Pilgrim to the Rose herself, seated on a bank of briar roses in front of the garden’s battlemented walls.

Morris also illustrated the story in print and designed a series of tapestries, of which the most famous is probably The Heart of the Rose. Apart from the giant rose the rest of the design bears considerable similarity to the earlier embroidery piece.

So despite my best research endeavours I’m afraid to say St Valentine has very little real connection with gardens and only a pretty tenuous one with love, red roses, heart-shaped cushions, cute little fluffy toys, romantic dinners or chocolates, but I don’t suppose that will stop many of us indulging in a little sentimentality in his name!

If this post has sparked your interest and you want to know more about ‘courtly love’ and the origins of ‘romance’ in its current sense then try looking at Pamela Porter’s Courtly Love in Medieval Manuscripts ( 2003) which is available on-line. Ruth Lee Webb’s A History of Valentines (1952)is worth a look too although the illustrations are only in black and white.

You must be logged in to post a comment.