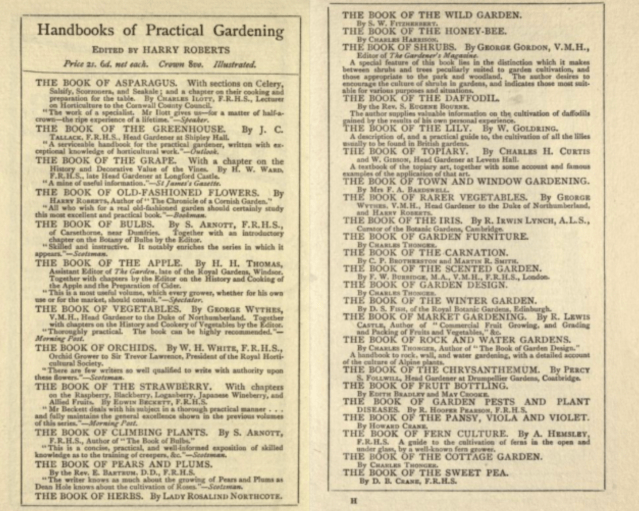

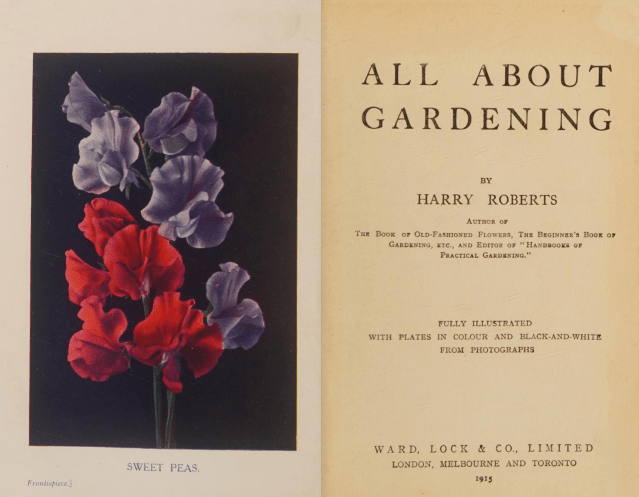

Browsing second-hand books a few months back I chanced up a shelf that had a stack of similar looking volumes which all came from a series called “Handbooks of Practical Gardening”. They covered almost every aspect of horticulture you can imagine from Asparagus Growing and Bee-Keeping to Daffodils and Fruit Bottling via Garden Pests, Window Gardening and Rarer Vegetables.

Browsing second-hand books a few months back I chanced up a shelf that had a stack of similar looking volumes which all came from a series called “Handbooks of Practical Gardening”. They covered almost every aspect of horticulture you can imagine from Asparagus Growing and Bee-Keeping to Daffodils and Fruit Bottling via Garden Pests, Window Gardening and Rarer Vegetables.

They were published in the first couple of decades of the last century, and then I noticed they were all edited by a man named Harry Roberts, who presumably must have known something about horticulture, but since I’d never heard of him I thought I’d see if I could find out more. It certainly wasn’t what I expected …

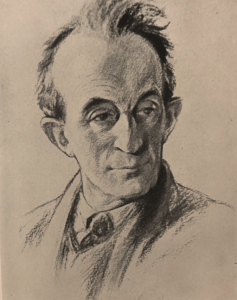

As usual I started with a quick Google search. It revealed almost nothing, nor does Harry Roberts appear in Ray Desmond’s Dictionary of British and Irish Gardeners, Botanists and Horticulturists. Next was a check on the British Newspaper Archive but the only person with that name who made the press was a London GP who cropped up occasionally writing books on public health, politics and even theology, without any mention of gardens. Obviously not the same person. However, without any other clue I thought I’d better check him out, and when I found his obituary things started to fall into place.

Harry from xxxx

Harry Roberts was born at Bishop’s Lydeard, in Somerset in 1871, and as a child he was “allowed a small strip of border under a sandstone wall for my very own”. He begged cutting and seeds so it wasn’t long before he “had become an ardent little botanist” and set up his own “museum”. His first book was written in 1880 at the ripe old age of 9 in one of those ruled school exercise books that were fashionable at the time. It was titled “School Botanical Gardens” and contained ” a few hints on the formation of a small garden for the study of the principal orders of plants, written for the use of school masters and others” Perhaps it was no wonder his school nickname was “Cocky Roberts.”

He started training as a doctor but changed his mind and taught science in secondary school for a few years. until it was discovered that he supported both the formation of Trades Unions and a local Socialist Society. He was then dismissed.

In 1890 he married and returned to complete his medical training, qualifying in 1895 and then buying a small one-man practice at Hayle in Cornwall where he could indulge in rural life – keeping bees, pigs and chickens – and create a garden alongside his work. Somehow, and I haven’t discovered how, this led in 1898 to a series of articles about the garden for Gardener’s Chronicle.

From The Chronicle of a Cornish Garden, 1901

These were spotted by John Lane who ran the Bodley Head Press and who was looking to diversify his publishing offer. Lane collated and republished them in 1901 as The Chronicle of a Cornish Garden, with some over-romanticised etchings by Frederick Griggs. The success of this led to Lane asking Roberts to commission and edit a whole series to be called “The Handbooks of Practical Gardening”. Harry wrote several titles himself but also contributed chapters to others. The books were aimed at novices and in the case of The Book of Old Fashioned Flowers also for “Homely Unaffected People Who Appreciate Homely Unassuming Flowers.”

Harry is always generous in his thanks to collaborators, and his editorial remarks reveal his really wide network of horticultural contacts which included most of the great and the good of the day.

The series came in a standard format: dust jacket, green cover with a stylised formal garden, around a dozen black and white photographs, plus line drawings or engravings, around 110-120 pages of text, and costing half-a-crown. As you can see there were an awful lot of them!

The dust jacket of Rarer Vegetables by George Wythes

Because he was determined that it should live up to its name Harry commissioned titles from really practical men including several leading Head Gardeners. Amongst them were John Tallack from Shipley Hall ; H.W.Ward of Longford Castle,, and George Wythes, head gardener to the Duke of Northumberland.

He definitely earned his title as editor. because despite the fact that Head Gardeners needed to be literate this did not necessarily make them good writers. In her “unorthodox biography” of Roberts, his partner Winifred Stamp said that sometimes when the manuscript arrived they were hand-written in cheap exercise-books, so while their practical information was very sound their English was often rather questionable and had to be largely rewritten.

However, most of the authors were not in that category. They were instead well-known garden writers like Harry Higgott Thomas, then Assistant Editor of The Garden, George Gordon, Editor of The Gardener’s Magazine, and C.H. Curtis who edited the Gardener’s Chronicle between 1918 and 1950. Others were by specialists. Iris was by Irwin Lynch, Curator of Cambridge Botanic Garden, while Lilies was by William Goldring, the landscape and garden designer, and The Scented Garden by Frederick Burbidge. of Kew and Trinity College Botanic Garden, Dublin.

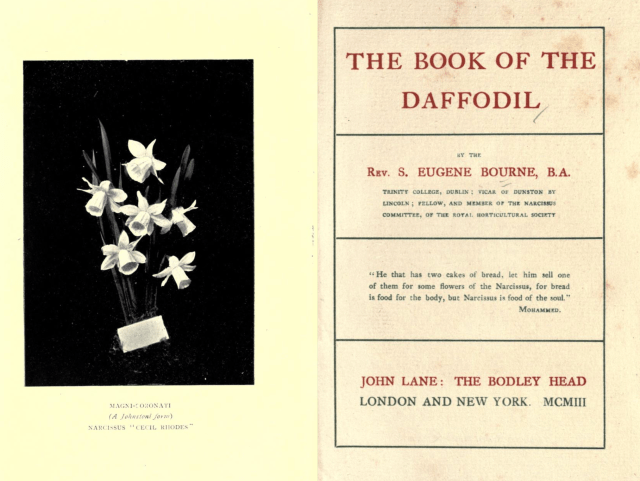

There were several volumes by leading amateurs including a couple of clergymen. Rev. Edward Bartrum, Headmaster of Berkhamsted School wrote about pears and plums, while the Rev. S. Eugene Bourne. covered daffodils. Samuel Arnott wrote about snowdrops and Martin R Smith, a wealthy banker wrote on carnations

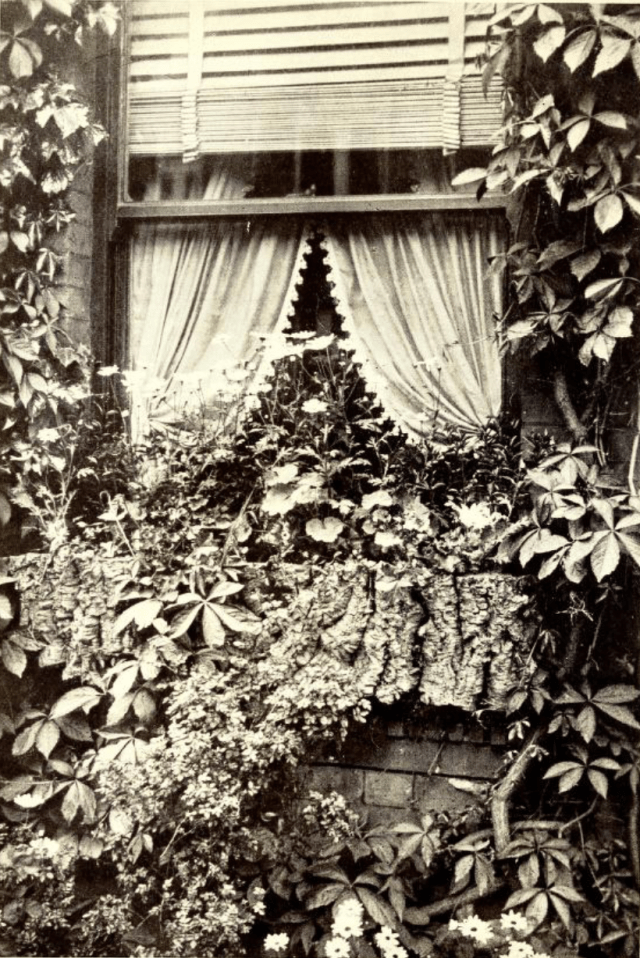

Two of these amateurs were women: Lady Rosalind Northcote did the book on herbs and Mrs F. A. Bardswell the volume on Town and Window Gardening:”A handbook for those lovers of flowers who are compelled to live in a town. The book should be helpful even to those who are quite ignorant in the art of growing plants, and advice is given as to the plants most suitable to the various adverse conditions which town gardens afford.”

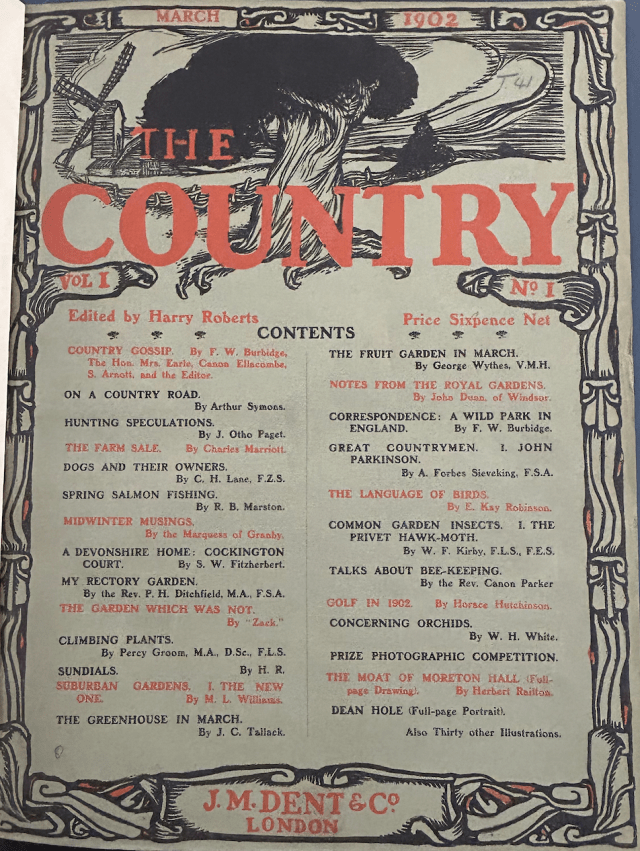

The success of the first few of these books gave Roberts the idea for The Country, a well illustrated and well produced glossy monthly magazine. It began inMarch 1902 with articles by many of those who had already written Practical Handbooks. Unfortunately it was not a financial success and only ran for eight issues before being wound up by the publishers.

The following year John Lane and Bodley Head brought out the Country Handbooks series, also edited by Harry, which began with his own Tramp’s Handbook, and went on to included a total of 15 books on various aspects of country pursuits and crafts.

All this while he was also building up his medical practice. He had also married and started a family. However, much though he loved Cornwall he decided to move to somewhere where he thought his skills would be of more use, and there would be more intellectual stimulation. In 1904 he sold his practice and after a couple of interim moves bought a run-down practice in Stepney in the East End of London, one of the most deprived communities in the country. It would appear this was also the time he parted amicably from his wife when she declined to accompany him, and from then on he lived with Winifred Stamp. Although she was described as his sister in the census of 1911 she was his partner and presumably sisterhood was thought a suitably respectable cover.

It’s worth quoting in full Winifred’s comments on the job he was taking on : “All that slum practice could offer him was squalid surroundings; dirty, noisy, swarming streets, no society of any kind … no fresh air, friends or schools for his children. Add to these drawbacks an income dependent on the smallest possible fees; drawn from patients who could seldom afford even that meagre amount” but “Harry Roberts, possessed with a passionate desire for justice to the underdog and for the assertion of individual rights.” His daughter was later to write that “ by the time the Health Insurance Act came into force in 1911, his practice was by far the largest and best run in East London. It had four doctors, one a woman, two qualified nurse midwives, a dentist and a masseur.”

Their new home and consulting room were in a little early 19th century terraced house which had a strip of garden with a small sycamore tree in it. They immediately began to garden: “I put in a tiny plant of jasmine at the kitchen door; [which ] in summer covered the whole back wall with white scented stars.” The house was destroyed by a German bombing raid during the war.

Harry was clearly a workaholic. [The rate at which he seemed to work – ie almost non-stop – reminds me of John Claudius Loudon].Not only a busy GP and editor, he also wrote a popular syndicated Medical Column, which appeared anonymously in various provincial papers, gardening articles for Queen magazine as well political articles for the socialist press. His life and work were driven by two underlying principles. He was both a Christian and a Socialist and even thought about putting his name forward as candidate for the newly formed Labour Party, but became disillusioned with them and withdrew. These two factors meant that alongside his medical practice and his garden writing he was also writing much broadly on political and religious subjects. As a result he had an extraordinary circle of friends including Havelock Ellis, Conrad Noel – known as “the Red Vicar of Thaxted”, GK Chesterton, CEM Joad, the humanist philosopher, the poet Edward Thomas and even Nancy Astor although apparently the two of them rowed endlessly.

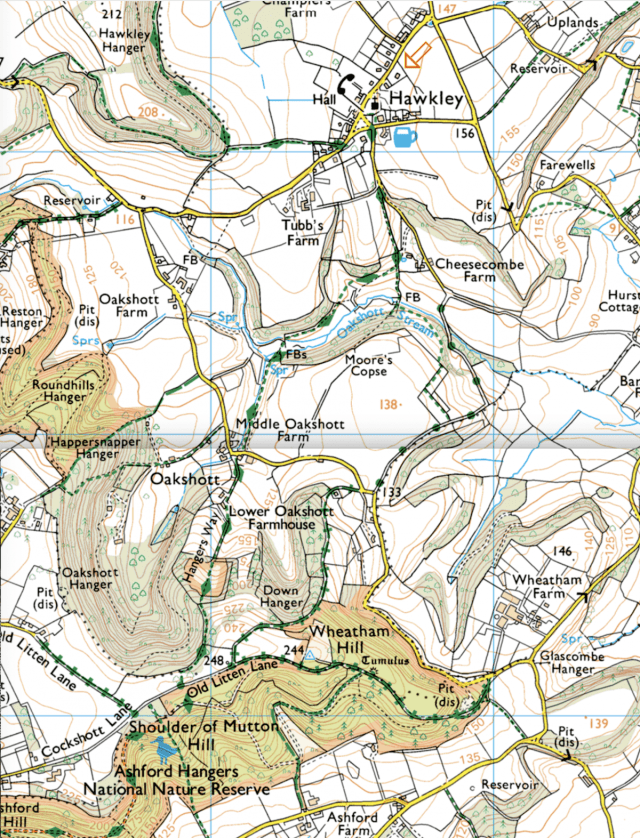

Oakshott Hanger is towards the bottom left of this OS extract. There is a house marked in the middle which I presume is the one they built. Just to the south of it Shoulder of Mutton Hill was favourite spot of their friend the poet Edward Thomas who is commemorated there.

Unsurprisingly the result of all this work was overwork! Eventually he was persuaded that for his own good he should find somewhere to unwind, relax – and garden.

A small ad in the Daily Mail [then not quite such an odd choice for a left-wing doctor to read] advertised a plot of 34 acres of woodland for sale at Hawkley in Hampshire, with the owners offering to meet potential purchasers at Petersfield railway station and drive them in a horse and cart to the site.

He and Winifred decided to go and see. After the five mile drive from the station the cart going steadily up a line of steep wooded hills called locally ‘hangers, the road “growing ever narrower and more overhung…at last we turned up a cart-track and the fly could go no further.” It was love at first sight – even if seen through rose-tinted spectacles. Winifred noted “we had no more qualms or questionings.” They bought it.

Its didn’t take long for the rose-tinting to wear off. Winifred explained that “thirty-four acres at ten pounds an acre swallowed up all our available capital. Till we could save a bit more, building was out of the question. In any case, as we realized, it wouldn’t be the simple, straightforward job that it had seemed.

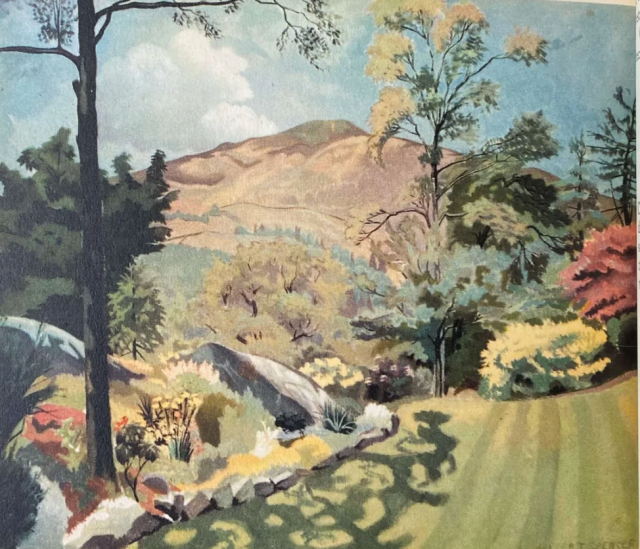

The site was largely thick woodland on one side of a valley, although a section lower down had been roughly cleared and was “a carpet of wild strawberries, thyme, marjoram, orchis, rock-rose, many-coloured milkwort and every sort of delicate chalk-loving plant.”

“On the plan there was a small cleared patch in the middle of the woodland which looked just right for the house; while the open strip seemed made by providence for a garden and vegetable plot. Finding that the whole thing was at an angle of about one in two upset most of our calculations. …, a house built on it might, we felt, slide to the bottom on a wet night. But in any case, a tent was all that we could afford until the next year at the earliest, and a tent it was.”

Once it was theirs they caught the last train down from London on a Saturday evening, and walked the 5 miles to Oakshott arriving at their tent in the early hours of the morning.

They planned the garden before the house, because it was more affordable. “At that time there was in the City an auction-room…where, after the orthodox time for bulb-planting, everything left over from the huge Dutch importations of daffodils, narcissi, tulips, snowdrops, scillas and so on, were sold off for what they would fetch…. fantastic bargains were to be had.. Harry would … go off loaded, for a few shillings, with bags of bulbs to be put in at the next weekend. Some of these first plantings still come up and flower each spring, unchanged after forty years.”

Eventually tiring of the tent Harry borrowed £500 from a rich friend and had a small house built, which could be extended over time. The builders had to cut into the hillside as, thanks to the steep slope, the biggest flat piece of ground was only about 12ft square!Next they set up an informal sanatorium and then built a series of huts for friends to use.

You can’t help admiring their optimism and commitment, and I love the way that they’d dealt with any financial problems “Harry and I had, over the years, come to the conclusion that the best rule for daily life, at any rate for people of our tastes, was to keep the level of necessity as low as possible so that one always had plenty to spare for luxuries.”

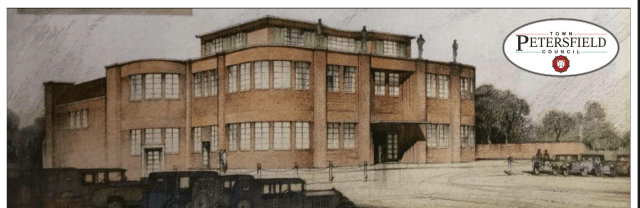

And then in 1918 as if all this was’t enough he set up a bookshop in nearby Petersfield. This was to lead in time to friendship with novelist Neville Shute, and the artist Stanley Spencer. He also got very involved in local life there and this led in 1935 to the building of the town’s own Festival Hall designed by Seeley and Paget of Eltham Palace fame to provide a home for the Petersfield Musical Festival.

He became a contributor to the wartime “Britain in Pictures” series, alongside Vita Saville West, Graham Greene, Edith Sitwell and Rose Macauley amongst many others. One volume was on British Rebels and Reformers but a second in 1944 was on English Gardens.

He became a contributor to the wartime “Britain in Pictures” series, alongside Vita Saville West, Graham Greene, Edith Sitwell and Rose Macauley amongst many others. One volume was on British Rebels and Reformers but a second in 1944 was on English Gardens.

In it he summed up his philosophy : “I like to be my own gardener and I take an interest in my plants as individual living things, as well as bits of beautiful colour and form. I like to see a plant grow and develop, to study its distinctive features, and their causes, and to read about it and so learn what others have observed. A small, convenient, and healthy house, a large and well-situated garden, a good library, gradually accumulated, a small competency – and what more in the way of physical possessions can the contemplative man require?”

Harry died suddenly just two years later in 1946. His medical practice continued to run under his partners and indeed still does, although obviously very differently. I’m sure he’d be proud of the continuing tradition

Towards the end of his life Harry Roberts was given an entry in Who’s Who where, although he doesn’t mention gardening, he described his Recreations as “Chatting with friends—old and new, reading, and the avoidance of uncongenial society”. Not a bad epitaph for such an extraordinary character

For more information: There are two short books about Harry Roberts. The first written after his death by Winifred Stamp. Unfortunately although it’s clear she shared his interest in gardening most of the book is about his politics and medical career which were closely interwtwined in the same way as they were with his contemporaries

For more information: There are two short books about Harry Roberts. The first written after his death by Winifred Stamp. Unfortunately although it’s clear she shared his interest in gardening most of the book is about his politics and medical career which were closely interwtwined in the same way as they were with his contemporaries

You must be logged in to post a comment.