I’m a hoarder and always have been. I’ve also been interested in history all my life and even as a child I collected anything and everything in the hope that one day it would come in ‘useful’. Having written last month that I loved decay in buildings and gardens, I remembered that when I was about 10 or 11 I’d gone to a jumble sale and bought a collection of Victorian illustrations from a subscription series called “Beautiful Britain” because it contained a photograph of the garden in the ruins of the mediaeval Farnham Castle, which was a few hundred yards from where I grew up.  And for the last 50 years or so its been waiting for its time to be useful. I finally remembered it as I was writing and eventually I tracked the folder down to a dusty cardboard box in my in-laws attic and glanced through the contents for the first time in at least a decade. And I was quite surprised.

And for the last 50 years or so its been waiting for its time to be useful. I finally remembered it as I was writing and eventually I tracked the folder down to a dusty cardboard box in my in-laws attic and glanced through the contents for the first time in at least a decade. And I was quite surprised.

The garden on top of the keep, Farnham Castle, Surrey from ‘Beautiful Britain’, 1894

The photo of the garden was there, looking even more extraordinary than I remembered it. That’s probably because I’d never looked at it, or any of the other pictures in the collection, with the eyes of a garden historian before. A couple of things struck me immediately as I looked through the rest of the folder. Firstly our ancestors were clearly sometimes happy to allow historic buildings and gardens to decay but still thought them beautiful because they were ‘romantic’. And secondly ivy was ubiquitous and allowed to grow almost anywhere it chose. Neither of these would really be acceptable today. Indeed one only has to look at recent photos of the same place to see how things have changed. We have become a national of obsessive heritage preservers and tidiers.

Is that a bad thing? Of course not…well not entirely. Our built heritage is precious and deserves our respect, care and attention. So too does our more ephemeral garden heritage. But this attitude is comparatively recent, indeed in the case of gardens very recent.

The old palace of Woodstock.

Reproduced by permission of English Heritage

NMR Reference Number: CC50/00455

Although antiquarians like John Leland, William Camden and William Dugdale had begun to investigate and write about antiquities in the 16th and 17th centuries, there was no sense in the ‘old’ was really considered of particular value. Buildings were demolished and gardens uprooted at will.

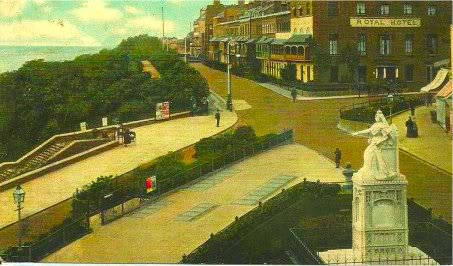

It was Sir John Vanbrugh who made the first serious attempt to preserve an old building for its own sake, not for living in but for its landscape value. As the architect of the new Blenheim Palace, the gift of a grateful nation to the Duke of Marlborough for his victories over Louis XIV, Vanbrugh wrote to the Duchess suggesting that the former royal palace of Woodstock, which stood in the park should be preserved rather than demolished. ‘It wou’d make One of the Most Agreable Objects that the best of Landskip Painters can invent. And if on the Contrary this Building is taken away; there then remains nothing but an Irregular, Ragged Ungovernable Hill, the deformitys of which are not be cured but by a Vast Expence.’ Unfortunately Vanbrugh lost the argument and the Duchess swept the ruins away.

Old Wardour Castle by Samuel & Nathaniel Buck, 1732

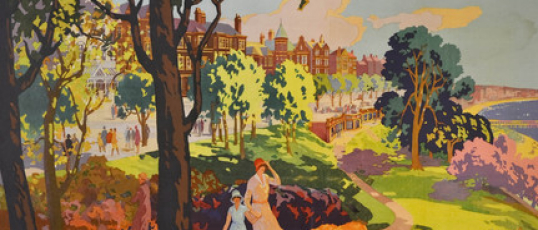

However, during the 18thc things began to change. Antiquarianism became an accepted pursuit for a gentleman, and coupled with a growing taste for topographical and landscape painting and prints, it encouraged the study of ancient monuments and mediaeval buildings and their settings. It is difficult to judge the extent of appreciation for their historical value but they were certainly valued for their visual attraction. Ruins, classical and gothic, both old and contrived, appeared in the gardens of the elite. At Wardour, for example, the ruins of the old castle were left as a picturesque eye-catcher in the distant landscape for the new house built a mile away.

Similarly at Rievaulx a new terrace high above the river valley spectacularly incorporates the old abbey ruins into the wider landscape of Duncombe Park.

And where they didn’t exist they could, as at Painshill, easily be created. The love of the old was however largely something indulged in only by the elite.

The Abbey, a sham ruin at Painshill © David Marsh 2008

Several things change in the early 19thc, partly inspired by Walter Scott’s series of Waverley novels which began in 1814. Scott began a new category of writing – historical fiction – and his stories together with those of slightly later writers like Harrison Ainsworth and Bulwer Lytton took hold of the public imagination and spread a love of history and the past amongst their readers. They encouraged the romantic notion of “Old England” which altered attitudes and perceptions to our ‘national story’ and what we would now call our ‘national heritage’.

Kenilworth Castle from ‘Beautiful Britain’, 1894

Simon Thurley points out in his recent book Men from the Ministry that Scott’s novels made the past tangible and realistic in a way previously unknown to a much wider audience. The sites he described like the castle at Ashby de la Zouche, the scene of the tournament in Ivanhoe [1819] became places of pilgrimage. Kenilworth Castle, the scene of the passionate but secret romance between Robert Dudley and Amy Robsart, was soon overrun with visitors, but this led to much better care of its fabric and to proper antiquarian study.

As travel became easier with the advent of the railways, travel books and tourist guides began to appear, and even for those who couldn’t travel to see the sights themselves there were not just books describing them but cheap magazines with illustrations. These were detailed, informative and peopled with evocative costumed figures. Although they mainly covered interiors they also included exteriors of famous places and even a few gardens. This opened up new romantic worlds to readers. But it also opened up the idea of a national history which was the birthright of all. Romantic history became patriotic.

The gardens of Levens Hall from Joseph Nash, The Mansions of England in the Olden Times, 1849

From there it was short step to Ruskin’s idea of important historical monuments and buildings being held not just by their owners but by the whole nation in a kind of trusteeship. In The Seven Lamps of Wisdom [1849] he argued that the buildings of the past did not belong to the current generation. ‘We have no right whatever to touch them. They are not ours. They belong partly to those who built them and partly to all generations of mankind who are to follow us.’

So what does that mean to us. We have accepted more than the idea of trusteeship. As a nation we ‘own’ a large number of historic houses and gardens, whether through English Heritage, or at slightly arms-length through the Royal Parks and Royal Palaces or the National Trust, and any number of smaller organisations, charitable trusts and volunteer groups. As a country we have also imposed restrictions on what the owners of such properties in private hands can do with them. But perhaps at a cost.

To be continued in the next post…..

For more information see

Farnham Castle & Park:

http://www.parksandgardens.org/places-and-people/site/4292/history Farnham Park

http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/daysout/properties/farnham-castle-keep/

Simon Thurley, Men from the Ministry [London: Yale University Press, 2013]

“Farnham Castle, Surry” from Francis Grose’s Antiquities of England and Wales, 1786

The gardens seems to have had an overhaul in the 1920s and was being restored in 2002 by the Heritage Lottery Fund when the landslip occurred.

The gardens seems to have had an overhaul in the 1920s and was being restored in 2002 by the Heritage Lottery Fund when the landslip occurred.

You must be logged in to post a comment.