There is a long history of philanthropic and/or paternalistic industrialists providing recreational and garden space for their employers. We’ve all heard of Bourneville, Port Sunlight and Saltaire, while Helena Chance’s recent book ‘The Factory in a Garden’. (2017) gives a comprehensive overview of such schemes in both Britain and the United States if you want to know more.

There is a long history of philanthropic and/or paternalistic industrialists providing recreational and garden space for their employers. We’ve all heard of Bourneville, Port Sunlight and Saltaire, while Helena Chance’s recent book ‘The Factory in a Garden’. (2017) gives a comprehensive overview of such schemes in both Britain and the United States if you want to know more.

However research, including by of all people, the American Space Agency [NASA] over the past 50 years or so clearly shows that it’s not just plants outside but those inside that are beneficial so houseplants are more than just green ornaments, they are good for your health too.

A 1989 NASA report concluded : “If man is to move into closed environments, on Earth or in space, he must take along nature’s life support system.” That’s because plants essentially do the opposite of what humans do when they breathe. They absorb carbon dioxide and release oxygen, and in the process refresh the air, and remove toxins. Other research shows that indoor plants reduce stress levels, make people feel good, promote concentration and as those earlier industrialists knew only too well, they help create a more contented workforce and increase productivity.

Today’s post is about a new post-industrial workspace packed with over 40,000 plants from all over the world in a group of three connected glass buildings which opened last year, and which I was lucky enough to be able to visit last weekend. You might be able to guess from the typeface and logo where I was and whose workforce this was designed for.

One subject that always seems to raise a lot of interest on the courses I run about the history of gardens is the mediaeval garden. Although most of us will have a vague picture of what we think they were like, the quest for the reality of mediaeval gardens and green open spaces is tantalising.

One subject that always seems to raise a lot of interest on the courses I run about the history of gardens is the mediaeval garden. Although most of us will have a vague picture of what we think they were like, the quest for the reality of mediaeval gardens and green open spaces is tantalising.

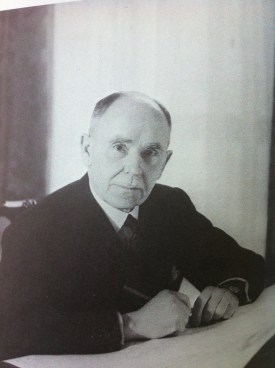

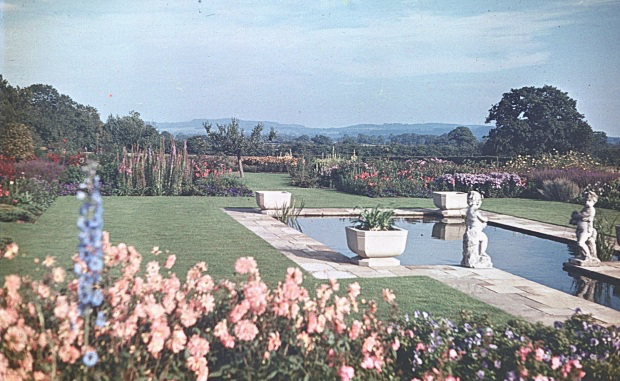

Last week’s introductory post about Percy Cane –

Last week’s introductory post about Percy Cane –

You must be logged in to post a comment.