Welcome to my 600th post! And to celebrate such a momentous occasion I’m turning today to the second of my garden-related humour posts and the genius of William Heath Robinson.

I was both surprised and delighted to discover that he was born just a few hundred yards from where I live in London, although admittedly he went up in the world, moving several times before ending up in Highgate, a mile or so [and several levels of social strata] up the hill from me.

As far as I know he’s also the only artist whose name has entered the English language with expressions such as “ hilarious and implausible contraptions he conjured up to carry out simple tasks and which led to him in the 1930s being dubbed “The Gadget King”. But there was more to him than just wonderful book illustrations and humorous drawings, and one of those things was gardening.

Unless otherwise acknowledged, the newspaper cartoons, come from items in the` British Newspaper Archive, and the images from How to Make A Garden Grow are taken from my copy.

Heath Robinson was born into a well-established family of commercial artists and illustrators in 1872. He gained a place the Royal Academy Schools but when he left in 1895 although he had ambitions to be a landscape painter, he realised that like many others before him including Gainsborough, that landscape painting did not pay the bills and so he followed his two older brothers into book illustration where he soon established a reputation for himself.

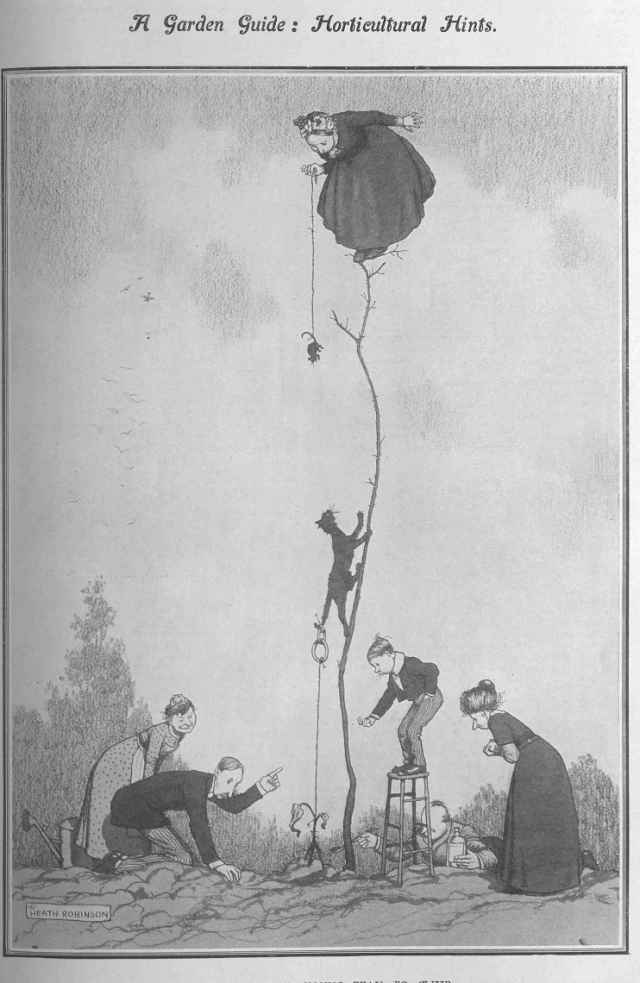

Training a young Bean to Climb, from The Sketch, 29th Nov 1911

Bedding out the perpetual spinach

The Sketch 18th Oct 1911

He then had a lucky break landing a job providing humorous cartoons for the weekly illustrated magazine The Sketch. These took a theme for a few weeks at a time and by 1911 he had turned his attention to gardening with a series entitled A Garden Guide: Horticultural Hints. Glossy magazines like The Sketch paid well for large, highly finished humorous drawings, and soon he had work appearing in The Tatler and The Bystander.

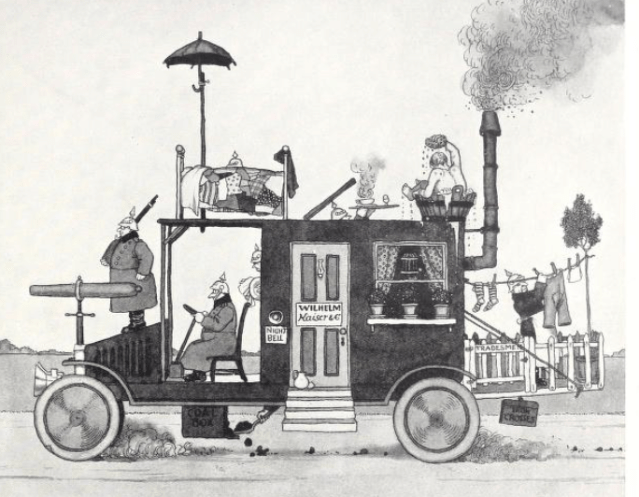

During the First World War, as with Reginald Arkell (of last week’s post), his gentle satires of the enemy proved popular not only with the public at home but made up for the decline in the demand for high quality book illustrations.

He even produced a book of them Some ‘frightful’ war pictures in 1915.

It was full of his weird and wonderful military inventions which were all designed to encourage laughter rather than horror in the viewer. I especially liked the one showing the Kaiser having a bath on top of his Imperial Campaigning Car.

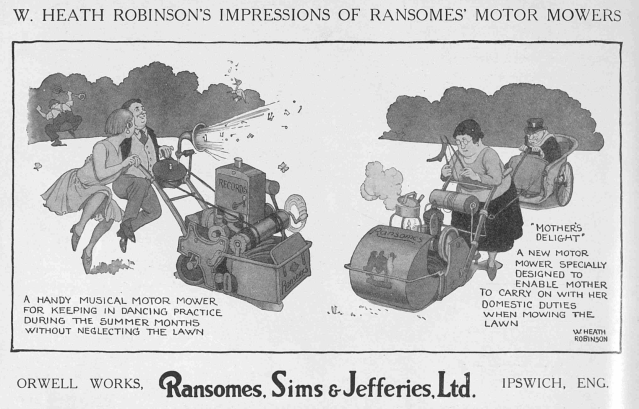

F rom The Tatler. 2nd May 1928

After the war although there were fewer commissions for illustrations there was increased demand for his cartoons from newspapers and magazines but also from advertisers.

from The Sketch 1st August 1923

During 1932 and 1933 Heath Robinson drew a series for The Sketch entitled ‘Flat Life’, which depicted various gadgets designed to make the most of the limited space available in the contemporary flat and satirising the more extreme designs in thirties furniture and architecture. It was this that started a successful collaboration with Kenneth R. G. Browne [the grandson of Phiz who had illustrated much of Dickens’ work]. In 1935 The Strand Magazine published an article titled ‘At Home with Heath Robinson’. written by Browne with ten of Robinson’s own pen and wash illustrations. His first full-length book How to Live in a Flat again with text by Browne was published for the Christmas market in 1936 and was well received.

Over the next three years Browne and Heath Robinson successfully repeated the formula in a further three titles. There was How to be a Perfect Husband, How to be a Motorist and the one that interests us most is How to Make a Garden Grow which appeared in 1938.

Over the next three years Browne and Heath Robinson successfully repeated the formula in a further three titles. There was How to be a Perfect Husband, How to be a Motorist and the one that interests us most is How to Make a Garden Grow which appeared in 1938.

As Geoffrey Beare, one of Heath Robinson’s biographers, pointed out there is a big difference between a one-off, or short series of cartoons published singly in a magazine or newspaper and cartoons published in a book. While the single one has to capture the reader and amuse them whatever their mood when they spot it, in a book the problem is sustaining that element of amusement through the whole volume as well as repeat visits. It means that Heath Robinson and Browne had offer readers many variations on a theme, although of course this meant they had the opportunity to explore gardening from every conceivable angle – and then, because he was Heath Robinson, from several more even more unlikely ones..

As Browne said “We need hardly say that months of research and experiment have gone to the making of this book. Although Mr. Heath Robinson’s window-box is a byword in the neighbourhood, while I can easily distinguish the scent of violets from that of a glue factory, we have not hitherto been known as really first-class gardeners.” This did not stop them trying.

“Nowadays gardening is a highly complicated science, bristling with Latin phrases and giving employment to a large number of deserving workers” who include “the manufacturers of hose-pipery, the designers of garden-rollers, the intrepid experts who insert the essential teeth in rakes, the knitters of netting for nut-trees,…the skilled craftsmen who operate the interlocutory bivalvular Hoppskotsch machines which impart the essential rotundity to the ball-bearings of lawn-mowers” etc etc.

“Nowadays gardening is a highly complicated science, bristling with Latin phrases and giving employment to a large number of deserving workers” who include “the manufacturers of hose-pipery, the designers of garden-rollers, the intrepid experts who insert the essential teeth in rakes, the knitters of netting for nut-trees,…the skilled craftsmen who operate the interlocutory bivalvular Hoppskotsch machines which impart the essential rotundity to the ball-bearings of lawn-mowers” etc etc.

Despite that not everybody “can cultivate the type of garden that gets its photograph in the glossier weekly papers and is visited by charabanc-loads of awestruck sightseers during the geranium season.” However “Almost anybody, however, who owns … a plot of ground, a pair of old trousers, a philosophic disposition and a little spare cash – wherewith to buy fertiliser, wallflower-bulbs, gardening-gloves and embrocation (for aches in the back, without which no gardener can properly discharge his duties) – can devise a modest pleasance in which tea can be taken on summer afternoons and which can be boasted about slightly at the Club.”

“It is enough to say that no expense has been spared, and no hardship shirked, in our efforts to compile a comprehensive textbook for the guidance of those who yearn to make two orchids grow where only plantains grew before.”

The book follows much the same path as a standard gardening manual. It begins with a chapter on Laying Out: “addressed chiefly to those whose garden, at the moment of going to press, is just a naked piece of Mother Earth, flowerless as the Mojave Desert and clamouring to be given a start in life – or “laid out”, as it is technically termed.” As in the examples seen in Sellar & Yeatman’s Garden Rubbish written a couple of years earlier [ see this an earlier post] an awful lot was crammed in.

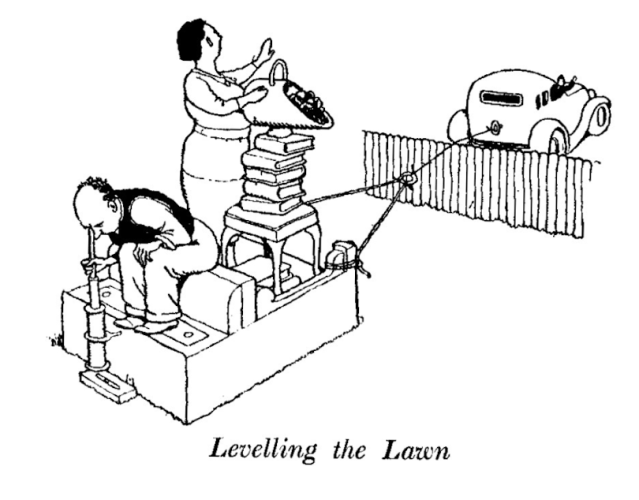

One example layout was for the sport loving gardener and included including lawns for tennis and croquet. These would probably require levelling and Heath Robison suggests a novel way of doing that with “the help of an upright piano, a couple of rather obese relatives, a borrowed motorcar and some stout rope.”

One example layout was for the sport loving gardener and included including lawns for tennis and croquet. These would probably require levelling and Heath Robison suggests a novel way of doing that with “the help of an upright piano, a couple of rather obese relatives, a borrowed motorcar and some stout rope.”

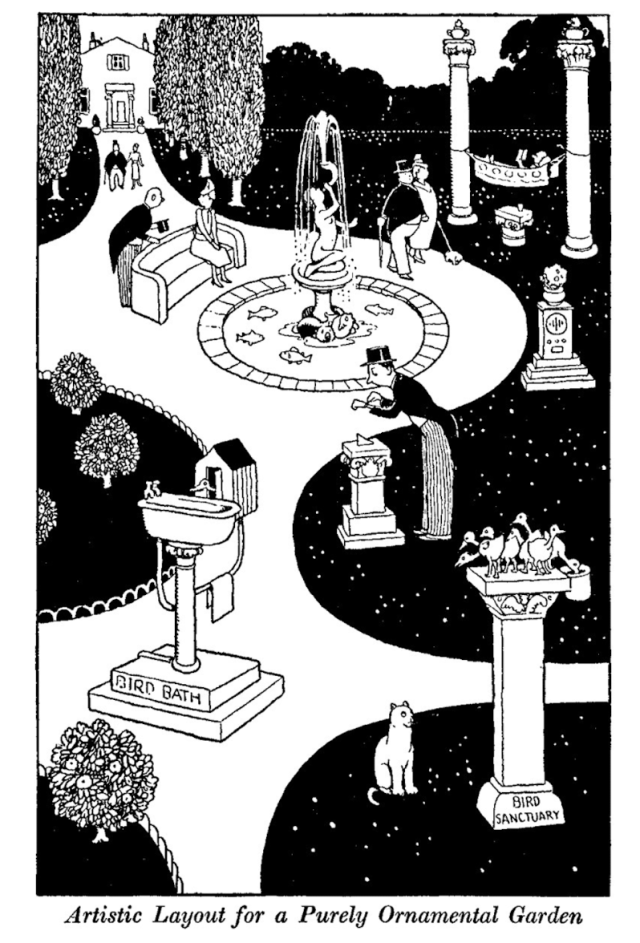

Alternatively the reader might prefer an ornamental garden so he also offered ideas for that: the hammock suspended between Greek columns is, Browne suggests “a particularly happy touch.” Notice too the latest design in bird baths complete with both hot and cold taps.

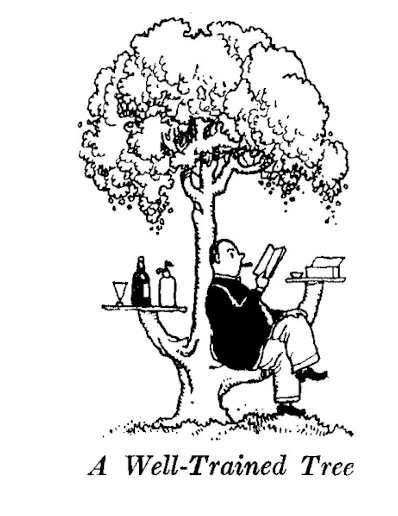

However probably neither of these “will appeal to the majority of beginners. The novice’s natural instinct is neither to play tennis nor to gape at statues, but to grow things – artichokes, antirrhinums, or whatever it may be – at once and in large quantities.” So Chapter 2 is all about Plants and Flowers. There is some basic advice about choosing trees and shrubs- “their shade is very pleasant to recline in with a good book. Washing can also be hung out on them, if it is that kind of neighbourhood.” Then choose a colour scheme but be warned “a garden containing only red is an affront to the eye… bulls and the retired military”. All white on the other hand “induces snow-blindness” and all yellow “just looks bilious”.

However probably neither of these “will appeal to the majority of beginners. The novice’s natural instinct is neither to play tennis nor to gape at statues, but to grow things – artichokes, antirrhinums, or whatever it may be – at once and in large quantities.” So Chapter 2 is all about Plants and Flowers. There is some basic advice about choosing trees and shrubs- “their shade is very pleasant to recline in with a good book. Washing can also be hung out on them, if it is that kind of neighbourhood.” Then choose a colour scheme but be warned “a garden containing only red is an affront to the eye… bulls and the retired military”. All white on the other hand “induces snow-blindness” and all yellow “just looks bilious”.

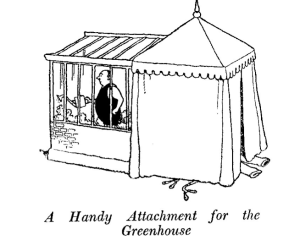

We are also reminded that some plants have “frail constitutions”, unlike hardy annuals, and require careful nursing in greenhouses.

Heath Robinson suggested adding a changing room when the gardener could “exchange their winter woolies for the latest in water-wear” in order to take advantage of the heat inside.

Having got your plants Chapter 3 tells you how to care for them, “for nature, in her inscrutable, wisdom, has decreed that where there is a garden. There shall also be (a) a lot of weeds and (b) a good deal of insect life, red in tooth and claw, and capable of eating anything from a pansy to a hollyhock; these must be persuaded of the error of their ways, if necessary by force.”

Heath Robinson, of course has the solution to the problem, or rather several solutions.

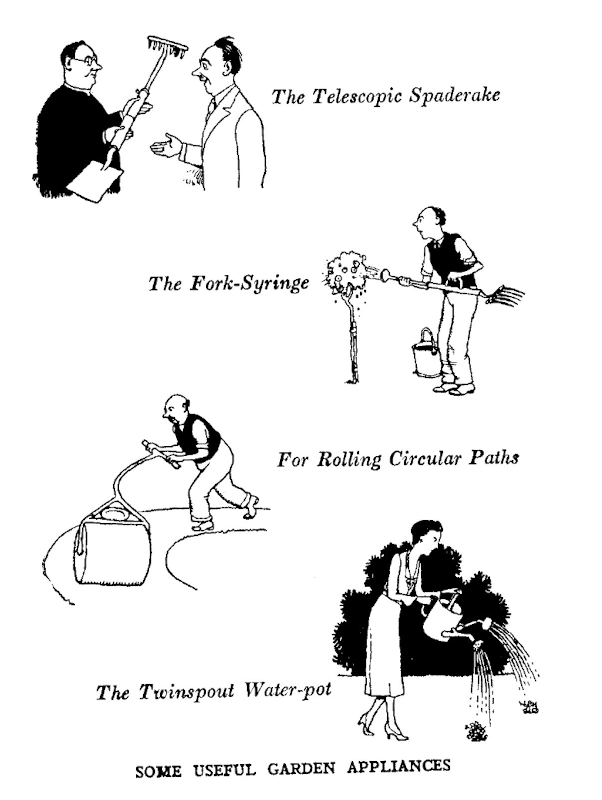

There is the one-woman-powered weeding contraption “to allow the weedsman to take the weight off his feet without treading on the flowerbeds”, a dethistleing machine and a trap for earwigs .as well as suggestions for dealing with greenfly, wireworms, and even avian pests. Discouraging cats too are the subject of another device together with the novel idea of training a tortoise to catch snails.

As chapter 4, explains though garden maintenance is not just a summer job. The garden must be “cherished all year round as carefully as if it were an aged and affluent aunt with no other relatives. In other words, the Gardner must almost continuously be on the job, toiling, reducing and borrowing occasional implements from a kindly neighbour.”

Seasonal differences are discussed in detail. such was how to spot when spring arrives, or in the summer “when. the gardeners chief duty is to protect his pleasaunce from the vagaries of the weather.”

Seasonal differences are discussed in detail. such was how to spot when spring arrives, or in the summer “when. the gardeners chief duty is to protect his pleasaunce from the vagaries of the weather.”

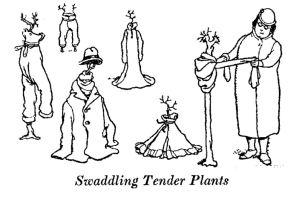

This often involves watering and again Heath Robinson comes up with some interesting ways of recycling water, for example, from your bath. He also noticed that sometimes plants need protecting from the weather particularly rain or strong wind.

The season can be extended through the autumn with carefully well thought out ideas for helping the trees to stay greener for longer. And winter need not be depressing, indeed the garden “can be made almost as attractive in December as in June. All that is required is a few artificial flowers preferably made from tin to withstand hailstorms one or two imitation Rose trees in frost-proof, zinc, a little synthetic heat in the form of portable oil, stoves, plenty of umbrellas, a lot of imagination and a set of warm woollen underwear for everybody.”

The season can be extended through the autumn with carefully well thought out ideas for helping the trees to stay greener for longer. And winter need not be depressing, indeed the garden “can be made almost as attractive in December as in June. All that is required is a few artificial flowers preferably made from tin to withstand hailstorms one or two imitation Rose trees in frost-proof, zinc, a little synthetic heat in the form of portable oil, stoves, plenty of umbrellas, a lot of imagination and a set of warm woollen underwear for everybody.”

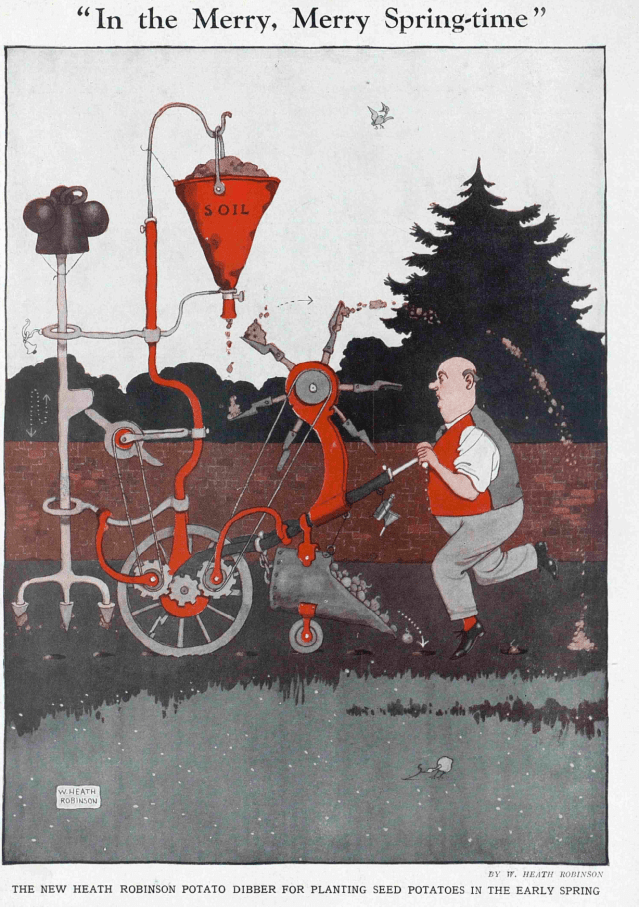

The kitchen garden formed the subject of chapter 5 because “many British gardeners are apt to feel occasionally they would like to grow some vegetables, if only for the rather melancholy pleasure of eating something they have known all its life. Thanks to Mr Heath Robinson, this ambition need no longer remain unfulfilled.”

The kitchen garden formed the subject of chapter 5 because “many British gardeners are apt to feel occasionally they would like to grow some vegetables, if only for the rather melancholy pleasure of eating something they have known all its life. Thanks to Mr Heath Robinson, this ambition need no longer remain unfulfilled.”

Garden fashions change all the time and the 1930s were the heyday of rock gardens and roof gardens and Chapter 6 covers these innovations. After all, there is no doubt “that a well planned rock garden, rich in arabis, aubretia, alyssum, arenaria, old Uncle Armaria, and all, adds a touch of distinction to the premises, and solves the problem of What To Do With That Corner By The Dustbin.”

Garden fashions change all the time and the 1930s were the heyday of rock gardens and roof gardens and Chapter 6 covers these innovations. After all, there is no doubt “that a well planned rock garden, rich in arabis, aubretia, alyssum, arenaria, old Uncle Armaria, and all, adds a touch of distinction to the premises, and solves the problem of What To Do With That Corner By The Dustbin.”

But where do the rocks come from?

True to form Mr Heath Robinson comes up with suggestions. It is a small step from gardening on rocks to gardening on the roof and again we are given creative ideas to combine them and make an attractive rock garden on rooftops or even window boxes.

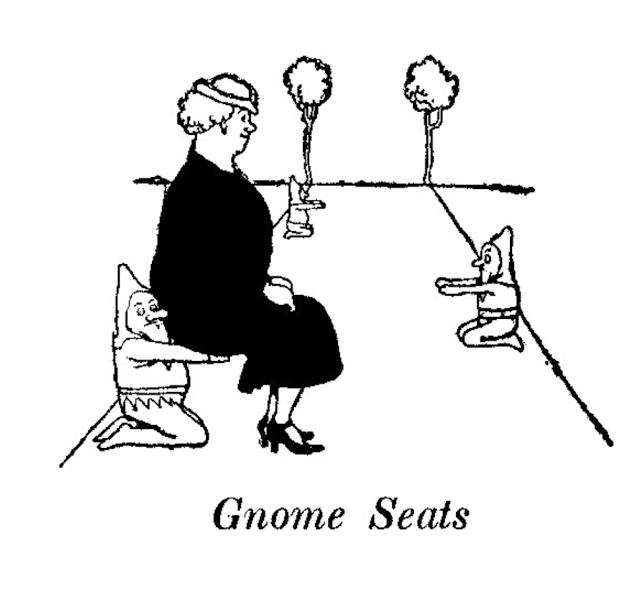

We now turn in chapter 7 to the subject of garden ornaments, such as statuary, birdbaths, or sundials and even the almost unspeakable “horrid rash to rush of little model gnomes, dwarfs, elves and similar whimsicalities.”

In choosing what to include “the gardener must be guided by his artistic sense, if any.” Browne has his own ideas: “life-size reproductions in Carrera marble of the Ways and Means Committee of the LCC would look all wrong amongst the wallflowers and tulips, as would a bronze effigy of a hippopotamus at play.

A statue of Eros, on the other hand, goes well with rhododendrons, and could be draped with trousers in the wink of an eye if the vicar calls unexpectedly.”

A statue of Eros, on the other hand, goes well with rhododendrons, and could be draped with trousers in the wink of an eye if the vicar calls unexpectedly.” And again, Heath Robinson comes up with some dual-purpose garden ornaments including several for gnomes since after all “fifty million gardeners cannot possibly be wrong” about them.

And again, Heath Robinson comes up with some dual-purpose garden ornaments including several for gnomes since after all “fifty million gardeners cannot possibly be wrong” about them.

Another popular form of ornament is of course topiary “the art or science of distorting bushes into amusing shapes, a fascinating hobby for an enterprising gardener. There is little about an ordinary bush to compel the eye or revoke the gasp of admiration; but a bush that has been pruned into the semblance of Mr Winston Churchill has a definite entertainment value and is equally nested in by aesthetically minded fowls.”However, ” it should be remembered that a topiarised bush needs pretty constant attention, as Nature has no respect for Art and is apt – usually at night, when nobody is looking -to add extra twigs etc, which may ruin the whole effect by giving it a faintly improper look”

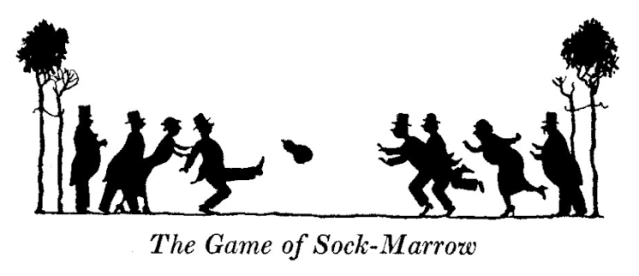

“There is clearly not much point in having a well groomed to garden, rich in Flora, and snails and whatnot, if one cannot use it to arouse the envy of the less fortunate” So Chapter 8 is all about garden entertainments such as garden parties, charity teas, tennis and similar genteel frolics although this might require some titivating of neglected areas and setting up some garden games. Of course, Mr Heath Robinson has some interesting ideas to help.

The book ends with a tailpiece which explains that ” it was impossible to do more than scratch the surface of the vast subject, of horticulture … and includes the confession that “neither Mr Heath Robinson, nor myself have ever grown any of the flowers or vegetables mentioned in this work” but this should not “detract from its educational value, or its usefulness as a flyswatter. ”

The book ends with a tailpiece which explains that ” it was impossible to do more than scratch the surface of the vast subject, of horticulture … and includes the confession that “neither Mr Heath Robinson, nor myself have ever grown any of the flowers or vegetables mentioned in this work” but this should not “detract from its educational value, or its usefulness as a flyswatter. ”

It also includes “certain byproducts of Mr Heath, Robinson’s fertile brain… which are designed solely to ease the gardeners manual lot, and could be constructed without much difficulty by anybody with a talent for such work…”

And of course, even after 600 posts, I share the sentiment behind Kenneth Browne’s epilogue: “Naturally, Mr Heath Robinson, and I expect no gratitude or fan-mail in return for our efforts on behalf of Britain’s gardening classes”

For more information the best place to start is with the website of the Heath Robinson Museum in Pinner where he lived for a time. If you have time there’s also a free on-line lecture about him by Luci Gosling on YouTube. Several of his books, or books about him can be found on Archive.org, including a good compilation called Contraptions edited by his biographer Geoffrey Beard. Unfortunately How to Make A Garden Grow is not one of them although it is easily available either second-hand or as an e-book. from Vintage Words of Wisdom Books.

For more information the best place to start is with the website of the Heath Robinson Museum in Pinner where he lived for a time. If you have time there’s also a free on-line lecture about him by Luci Gosling on YouTube. Several of his books, or books about him can be found on Archive.org, including a good compilation called Contraptions edited by his biographer Geoffrey Beard. Unfortunately How to Make A Garden Grow is not one of them although it is easily available either second-hand or as an e-book. from Vintage Words of Wisdom Books.

from The Bystander, 10th March 1926

You must be logged in to post a comment.