Parr of the School of Horticulture building in Niagara Botanical Gardens

What is Niagara doing on a blog. about the history of parks and gardens?

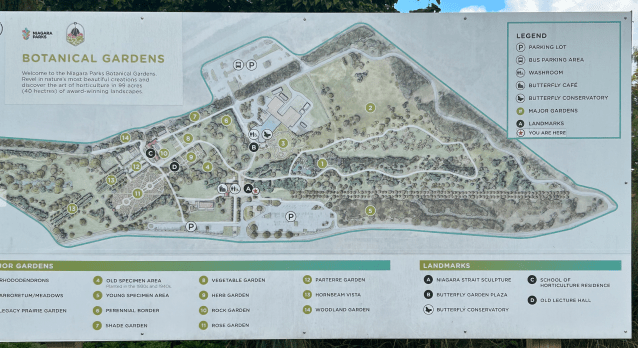

Well, if,like me until last week, you thought that Niagara meant only the world famous Falls and nothing else, you might be surprised to know there are other less heralded, indeed almost unknown, important sights within easy distance of the Falls: the area’s gardens and parks – many of them historic. They are some of the best planted and maintained examples of public planting I have seen anywhere, a mix of the high quality and very colourful Victorian-style bedding and modern sustainable planting, often using indigenous plant. There’s also a historic floral clock, a 99 acre [44 ha] botanic garden, and a world class horticultural college, as well as a whole range of nature conservation and environmental stewardship projects.

I should confess that I’d mentioned one of these gardens in a post way back in June 2023 but had completely forgotten about it until I walked into it last week on holiday in Canada! So give yourself a gold star if you remember who designed the garden in the photo below, otherwise read on to discover more…

As usual the images are my own unless otherwise acknowledged

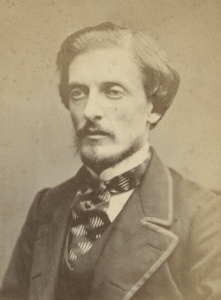

Niagara by Frederick Church. 1857 The painting is enormous at 101 x229cm or 40x 90 inches

The Niagara River is the boundary between Canada and the USA, and so the Falls are divided between the two countries. Ideas about founding what is effectively national parks on both sides of the Falls began as early as the 1850s when Frederic Church, the American landscape artist began a campaign to prevent unwelcome industrialisation and commercialization, and establish public parks along each side of the Canadian and American borders.

His paintings of the Falls were crowd pullers and the one above was even exhibited widely in Europe. It changed attitudes. He was joined in his efforts in 1869 by Frederick Law Olmstead, the American landscape architect, and gradually the campaign took off. [For more on this see “Heritage Moments: Frederick Law Olmsted and the stroll that saved Niagara”].

Lord Dufferin, Governor-General of Canada, announced his support in 1878 and was joined the following year by Governor Robinson of New York State. On the Canadian side, after some dispute about who was to pay for the park, 19 private properties were expropriated and on Victoria Day, April 23rd 1887, “the Queen Victoria Niagara Parks Act” was passed and the 154 acre park officially opened at a cost of $436,813.24.

The Act established the Niagara Parks Commission and over the years its remit has grown substantially so it now owns and maintains over 4,250 acres [1720 ha] of parkland along the entire length of the Niagara River.

The Act established the Niagara Parks Commission and over the years its remit has grown substantially so it now owns and maintains over 4,250 acres [1720 ha] of parkland along the entire length of the Niagara River.

It is highly unusual for a government agency, in that it receives no government financing but raises its own revenues through gift shops, golf courses, restaurants, attractions and, of course, parking charges. It’s a very interesting funding model although only possible because of the monopoly they hold over all the services used by the vast crowds of tourists who visit every day, and clearly bring in an enormous amount of cash. Its 12 commissioners meet monthly mainly in public and run their own police services, organise road maintenance, waste collection, and all other necessary services but what is clear is that a lot of the money raised is reinvested in public open and green spaces. You can see the range of the Parks Commissions activities and financing in their latest monthly report.

Once I started researching I soon discovered that the Commission started out without much money, but rapidly developed an entreprenial streak, leasing out concessions and rights to raise the money to keep the parks free. Otherwise not that much happened in the first 50 years of their existence but everything changed almost a hundred years ago. It was the time of the Great Depression which started in 1929, and, just as in the USA with Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, one of the responses in Canada was to look for schemes that might serve the public good and also help deal with high levels of unemployment. Niagara is a prime example of its success.

The Zimmerman Founatin

The Zimmerman Fountain

The area around Niagara had a small settlement named Clifton which was home to one of Canada’s early railway and banking magnates the self -made Samuel Zimmerman. In the early 1850s he began building a mansion known as Clifton Place, which had four large gatehouses, extensive gardens and a large but plain fountain. Unfortunately he died in an accident before it was finished and the estate was bought by an American Senator, John Bush who redesigned the house as a vast Italian villa and whose family lived there until 1927. The estate was then sold to Harry Oakes, a mining entrepreneur. In 1937 despite a huge public outcry the mansion was torn down and the site developed. All that remains is the fountain, now named after Zimmerman, which forms the centrepiece of Queen Victoria Gardens.

There are lots more photos of the gardens, including many historic ones, on the website of the local library.

Queen Victoria Gardens, with the Parks Police HQ and the Falls

Queen Victoria Gardens are not all formal, and like many other Canadian public parks space has been made, even in such a prominent site, for a more “natural” section featuring indigenous plants.

Queen Victoria Gardens are not all formal, and like many other Canadian public parks space has been made, even in such a prominent site, for a more “natural” section featuring indigenous plants.

Further along the edge of the Falls was the grand Clifton House Hotel , “an architectural beauty, … [with] no superior in the world.” Unfortunately it burned down in 1932. The site was then also acquired by Harry Oakes, who was all accounts quite a difficult man to work for and with, perhaps because by then he was probably the richest man in Canada. Nevertheless he was a generous philanthropist. In 1930 he had, for example, funded a make-work project by giving 16 acres to the local council to create Oakes Park , still the city’s biggest sporting facility. More importantly for this post he did a deal with the Niagara Parks Commission around 1934, swapping the site of the hotel for some other small sections of land elsewhere and this allowed them to create the most significant of the main Niagara area’s public green spaces: Oakes Theatre Gardens.

The gardens are impressive for their design and planting and are very much of their time. Equally importantly, these days they serve to highlight the importance of the setting and surroundings of a site and how they impact on its significance. When Oakes theatre Gardens were first opened they had no visual competition but nowadays unfortunately they are completely overshadowed by massive slabs of glass and concrete which dominate the Niagara skyline. It takes quite an effort for a visitor’s view and appreciation not to be affected .

I mentioned these gardens in a post a few years back about the life of the pioneering female landscape architect Lorrie Dunington and her husband Howard Grubb. They designed the grounds and collaborated with the architect William Lyon Somerville to use the natural contours of the land to create a series of gardens around a central sloping fan-shaped grass amphitheatre. One of these incorporate part of the foundation wall of the old Clifton Hotel.

At the top of the site there is a long sweeping curved stone arcade that connects two open pavilions, one aligned to give a view of the American Falls and the other of the Horseshoe Falls.

At the top of the site there is a long sweeping curved stone arcade that connects two open pavilions, one aligned to give a view of the American Falls and the other of the Horseshoe Falls.

Around the amphitheatre are a series of other smaller much more formal spaces which incorporate traditional elements such as flights of stone steps, balustrading, a formal pond and fountain, paved terraces, urns and pleached tree walks reminiscent of parks in Paris.

To my surprise I also discovered a completely different garden behind the arcade, which as far as I can tell was designed by the Dunington-Grubbs too. The reason it’s difficult to be certain is that there is almost no mention of the Dunington-Grubbs anywhere on the site, and very little on-line. Their part in creating the gardens seems to have been overlooked if not forgotten.

To my surprise I also discovered a completely different garden behind the arcade, which as far as I can tell was designed by the Dunington-Grubbs too. The reason it’s difficult to be certain is that there is almost no mention of the Dunington-Grubbs anywhere on the site, and very little on-line. Their part in creating the gardens seems to have been overlooked if not forgotten.

This hidden section is informal, shady and heavily planted with trees and shrubs around a pool and bridge, and can be reached independently of the rest of the gardens, as well as from doorways in the back of the arcade.

The Oakes Garden Theatre opened in September 1937. By then Oakes had left Canada for the Bahamas for tax reasons but was made a baronet by George VI for his philanthropic work in 1939. [For more on him and, to get your attention, his murder, click here ]. A few years later the gardens were extended when the Rainbow Bridge, which you can just make out in the background of the image below, over the river to Buffalo in New York State was opened.

The arcade [sometimes described as a pergola locally] was reconstructed in 2017 and the whole garden subsequently restored.

The arcade [sometimes described as a pergola locally] was reconstructed in 2017 and the whole garden subsequently restored.

There are lots more photos of the garden theatre, again including many historic ones, on the website in the local library.

While Queen Victoria Gardens and Oakes Garden Theatre are now dominated by new buildings what has not been similarly overshadowed are the Commissions garden-related projects further down the Niagara Valley. I just want to mention a couple of them because they tie in neatly with Canada’s response to the Great Depression.

The 1930s also saw the Niagara Parks Commission expand its horticultural and gardens interest much further. One factor in this is their response to a growing need for skilled gardeners. Up until this point despite calls for a local training scheme dating back to before the First World War, the shortage had mainly been addressed by the easier option of recruiting experienced gardeners from Europe. However by the time of the Depression this was no longer a sustainable option and they decided to up-skill and recruit locally instead.

From one of the information boards

from one of the information boards

In 1936 they established a Training School for Apprentice Gardeners, based on the longstanding apprenticeship scheme offered at Kew. At first only single men were admitted and indeed it was another 40 years before, in 1976, the first female student was enrolled. In the early years these men were required to have already some work experience in horticulture, and to agree to work for the Commission of at least 3 years after graduating. To give them a real hands-on task their first project was to lay out a new botanical garden. That sounds easier than it obviously was.

The old lecture h alltoday – still in use but with more modern ones added too

The new Training School and Botanic Garden started out on just under 100 acres of neglected poor quality grassland and progress was gradual. Eight students were recruited in the first year, an existing house was enlarged to form residential quarters for them, a lecture room was converted from an old railway station and driveways and walkways, were constructed, while they also started the search for plants.

the residential block today

and its rear extension

That first year saw the new superintendent of the school travel to Holland to find suitable stock and returning with the largest order that had ever been shipped from Dutch nurseries, including many non-indigenous plants which he thought suitable for trialling around Niagara.

By 1942 an arboretum had been established complete with trees from all over North America and Europe. A collection of perennials was amassed and a nursery established to propagate and supply specimen plants by the thousand for use throughout the rest of Commissions land. As their website puts it “although it is referred to as the ‘gentle art of gardening’ by some, it was incredibly intensive labour mostly done by hand and horses instead of machines.”

The students also had to grow much of their own food, as well as keep chickens and pigs, whilst additional vegetables and fruit were grown to supply the Commission’s restaurants and cafes.

Since then the Training School has evolved finally becoming the Niagara Parks School of Horticulture in 1990.

It was Canada’s first and only residential school for horticultural students. As in the earliest days the Botanic Garden still functions as a living classroom and the small number of students -currently an intake of only around 15 each year – are responsible for cultivating and maintaining 90% of the site. Perhaps unsurprisingly there is a 100% success rate in students gaining employment with students often approached with offers in their first year of training.

It was Canada’s first and only residential school for horticultural students. As in the earliest days the Botanic Garden still functions as a living classroom and the small number of students -currently an intake of only around 15 each year – are responsible for cultivating and maintaining 90% of the site. Perhaps unsurprisingly there is a 100% success rate in students gaining employment with students often approached with offers in their first year of training.

As you’d expect the grounds have continued to evolve. There is a large rose garden laid out in the earliest days near the old lecture hall, now containing well over 2000 specimens as well as associated companion planting and with a grand wooden pergola as a backdrop. Rather than try and describe all the other areas I’ve just added some photos…

and there is a legacy prairie garden, which considering the comparatively limited range of indigenous plants, and the time of year was surprisingly interesting.

Last but not least there’s a floral clock on an a nearby Commission site which was installed in 1950 and which they claim is the second most photographed site locally after the Falls.

Last but not least there’s a floral clock on an a nearby Commission site which was installed in 1950 and which they claim is the second most photographed site locally after the Falls.

Judging by the number of people there when I saw it I’m not surprised. The clock is 12 metres across, making it one of the largest in the world, and includes over 20,000 bedding plants which are changed seasonally. The tower behind houses a recording of the Westminster Chimes which ring out very loudly every 15 minutes. The Commission claim “It’s a living celebration of horticultural excellence, showcasing the creativity, care, and green spaces of Niagara Parks,” and I’m sure if you like floral clocks that’s true!

Judging by the number of people there when I saw it I’m not surprised. The clock is 12 metres across, making it one of the largest in the world, and includes over 20,000 bedding plants which are changed seasonally. The tower behind houses a recording of the Westminster Chimes which ring out very loudly every 15 minutes. The Commission claim “It’s a living celebration of horticultural excellence, showcasing the creativity, care, and green spaces of Niagara Parks,” and I’m sure if you like floral clocks that’s true!

For more on Floral Clocks more generally see these two earlier posts: Floral Clocks and Oh I do like to tick beside the seaside

If I’m honest I have been surprised and impressed by Canada’s gardens and parks and I hope to share some more of the reasons for my new found enthusiasm over the next few weeks – so be prepared!

You must be logged in to post a comment.