from the Aztec Herbal

Gardens and medicine are closely intertwined in every culture, and were even more so in the past when most remedies were derived from plants. Yet much of that knowledge has been lost and I suspect few of us these days would have a clue about their useful properties – the only one I can think of immediately is using dock leaves to counter nettle stings. So perhaps you can imagine the surprise on the face of Dr. Charles Clark when he discovered the subject of this post in the Vatican Library in 1929.

Now usually known as the Aztec Herbal it turned out to be a remarkable find- although probably not really because of the efficacy of its medical recommendations or even of its horticultural significance. I’m not sure you’d want to try its suggested treatments either- but even if you did you might have problems finding them. Read on to find out more about the gardens where these plants grew and which ones could help if you have a headache, scabies, a pain in the eye or worse….

Unless otherwise acknowledged the images are scanned from The Royal Collections Trust edition of the two surviving versions of the text, I’ve also used images from the slightly later Florentine Codex which covers Aztec life more generally. Apologies for the quality of some of them but the originals are often very small and so haven’t enlarged that well.

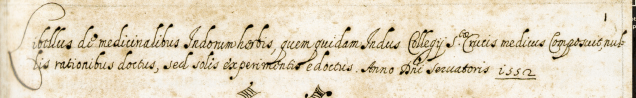

The opening lines in Latin of the herbal

While Charles Clark was actually looking for material about the early history of the Americas what he found was a long-forgotten hand-written and illustrated volume called Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis. Written in 1552 the translation of the introduction begins “A little book of Indian medicinal herbs composed by a certain Indian, physician of the College of Santa Cruz, who has no theoretical learning, but is well taught by experience alone.”

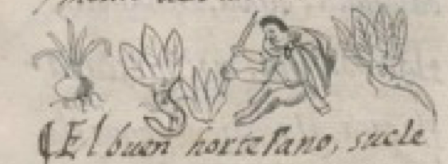

From Book 10 of the Florentine Codex

That we have any knowledge of Aztec gardens and gardening at all is a small miracle. Not only are there no surviving gardens but there are no extant images or plans either. Yet it’s clear from early Spanish accounts that, by the time of the conquest of Mexico between 1519 and 1521, Aztec gardening and medicinal botany had reached a high degree of sophistication, and that flowers played an important part in religious life.

From Book 10 of the Florentine Codex

According to Phil Clark’s A Flower Lover’s Guide to Mexico the Aztecs had developed a system for naming plants, based on their key characteristics (appearance, colour, habitat, medicinal properties etc.) and had selected strains of plants that displayed unusual characteristics such as double-flowering marigolds and dahlias. It has led to suggestions that the Aztecs had in effect created the world’s first botanical gardens and that early examples in Europe were inspired by what the conquistadors saw. [For more on this see The Garden of the Aztec Philosopher King by Susan Toby Evans which is about a 15thc Aztec royal landscaper designer]

From Book 10 of the Florentine Codex

The last Aztec Emperor Moctezuma II had gardens just for flowers in which, according to the chronicler, Cervantes de Salazar, he “did not allow any vegetables or fruit to be grown, saying that it was not kingly to cultivate plants for utility or profit in his pleasance”. He also owned vegetable gardens and orchards, but these he seldom visited, since he held them to be “for slaves or merchants”. However his dismissal of such utilitarian gardens did not extend to medicinal plants, which he highly prized and were well-looked after.

Descriptions of other royal Aztec gardens also survive. Writing to the Emperor Charles V, Hernan Cortés the Spanish leader described the palace garden of Moctezuma’s brother at Iztapalapa as

“very refreshing with many trees and sweet-scented flowers, bathing places of fresh water … Within the orchard is a great square pool of fresh water, very well constructed, with sides of handsome masonry, around which runs a walk with a well-laid pavement of tiles, so wide that four persons can walk abreast on it, and 400 paces square, making in all 1,600 paces. On the other side of this promenade toward the wall of the garden are hedges of lattice work made of cane, behind which are all sorts of plantations of trees and aromatic herbs. The pool contains many fish and different kinds of waterfowl.”

From Book XI of the Florentine Codex

Bernal Díaz del Castillo , one of the conquistadors, thought the tropical garden at Huaxtepec “the best that I have ever seen in all my life.” This probably isn’t surprising because its boundaries stretched to seven miles around contained at least 2000 species of plants brought from all parts of the empire, such as cacao, vanilla orchids and magnolia but also crucially many medicinal plants.

Huaxtepec was also visited by the great natural historian Francisco Hernández, sent by the Spanish king to document New Spain and its flora. That took 7 years and he still did’t finish but he was full of praise for the extent of botanical and taxonomical knowledge of the indigenous people. “I marvelled… there are so many herbs, some with known uses and some without, but there is almost none, which is not known to them and given a particular name.”

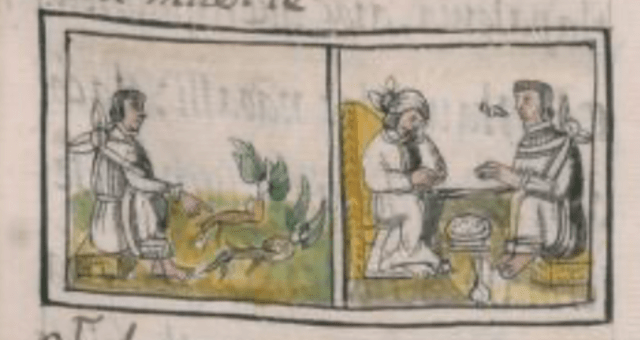

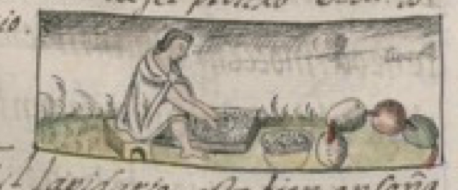

An apothecary collecting and then administering herbs, from Book 10 of the Florentine Codex

Cortes too commented on this, writing that in Tenochitlan, the Aztec capital [now Mexico City] there was “a street of herb sellers where there are all manner of roots and medicinal plants that are found in the land. There are houses of apothecaries where they sell medicines made from those herbs both for drinking and for use as ointments and salves.”

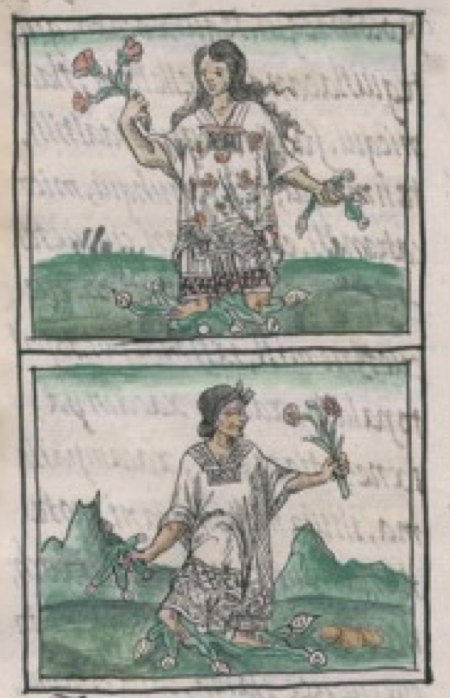

Gathering flowers from Book 11 of the Florentine Codex

From Book 10 of the Florentine Codex

Yet all of this was quickly destroyed either deliberately or by neglect by the Spanish, with Bernal Díaz summing this up by writing “that never in the world would there be discovered other lands such as these… Of all these wonders that I then beheld today all is overthrown and lost, nothing left standing.”

Along with the destruction of the gardens and libraries went much else of indigenous culture in conquerors drive to impose Christianity on their new subjects. Next the Spanish did what colonising powers often do, and built schools and colleges to educate the young in their own, rather than traditional, culture.In Mexico it was done so well that in less than twenty years after the conquest there were indigenous boys who “spoke Latin as elegantly as Cicero.”

From Book XI of the Florentine Codex

The first one of these institutions was the College of Santa Cruz founded by the Franciscans in 1536 where one of the early teachers was Father Bernardino de Sahagún who was to produce a very lengthy 12 volume manuscript with more than 2000 images of life in New Spain [ie Mexico] at the time. This is now known as the Florentine Codex [available on-line at the Library of Congress] and includes a long section about the flora and fauna of the country.

From Book 10 of the Florentine Codex

So, despite its name, the so-called Aztec Herbal isn’t an Aztec survival but one written about 30 years after the conquest, at Santa Cruz by two of those indigenous boys known now only by their westernised names after their conversion to Christianity. Martin de la Cruz, the compiler, had become a teacher of native medicine and Juan Badiano, the translator was ‘Reader in Latin,’ at the college. The manuscript contains 185 very basic painted images of plants, probably by Martin, with an accompanying Latin text describing their medicinal uses by Juan. As a result the manuscript is usually known as the Codex Badianus. Unfortunately Juan couldn’t find Latin equivalents for most plant names, probably because the plants were unknown in the west, and so he had little choice other than to keep the original Aztec names. It’s also interesting that, although most of the text is in Latin it also uses Nahuatl which had no written form until the Franciscans taught de la Cruz to write it phonetically.

Herbs for treating [left] mental stupor [right] foetid odour of the infirm From Codex Badianus

For more on the European influences see Jose Valverde’s article on the Aztec Herbal on Researchgate

Herbs for dealing with [left to right] Pain in the side; small creatures in the abdomen; worms ; and a general antidote. from the Codex Badianus

Herbs for treating [left to right] dandruff; scabies; falling hair from the Codex Badianus

Don Francisco sent the completed volume over to the Emperor Charles V in Spain where it went into the royal library. There, along with much else from the New World, it remained hidden away and hardly used or studied apart from by the royal apothecary Diego de Cortavila y Sanabria who even wrote his name on it. In 1626 Cardinal Francesco Barberini the Vatican’s ambassador to Spain visited Cortavila’s garden where he grew “various curious Indian plants which he gave to the cardinal”. Cortavila also “presented Barbarini with a small volume of various Indian simples containing their associated virtues for ailments of the human body.”

Herbs for treating [left to right] Haemorrhoids; genital warts; excessive heat from the Windsor Copy of the Codex Badianus

Illustrations of the same herbs from the original Codex badianus

Cassiano dal Pozzo (1588–1657) unknown artist c1626

Barbarini’s secretary was a scholar named Cassiano dal Pozzo, and he was intrigued enough to have a copy of the manuscript made and included in what has become known as his Paper Museum [which deserves a post of its own one day] . The images in the copy are much more sophisticated and slightly larger than the original whilst the artists [at least 2 have been identified] also reorganised it into larger pages so the two versions are not identical.

Dal Pozzo’s copy was sold by his heirs to Pope Clement XI who later sold it on to his nephew Cardinal Alessandro Albani, a great collector and gardener. [for more about him and his gardens see this earlier post]. In 1762 Albani sold it to King George III since when it’s been in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle. In 2009 it was published in a well-edited luxury edition as part of the publication by the library of all of dal Pozzo’s Paper Museum. This is the one I’m calling the Windsor Copy.

Dal Pozzo’s copy was sold by his heirs to Pope Clement XI who later sold it on to his nephew Cardinal Alessandro Albani, a great collector and gardener. [for more about him and his gardens see this earlier post]. In 1762 Albani sold it to King George III since when it’s been in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle. In 2009 it was published in a well-edited luxury edition as part of the publication by the library of all of dal Pozzo’s Paper Museum. This is the one I’m calling the Windsor Copy.

Herbs for treating head problems and boils from the Windsor Copy

Meanwhile the original remained in the Barberini library equally forgotten until, in 1902, that library was acquired by that of the Vatican. It remained “hidden” there until 1929 when Dr Clark unearthed it again. Its final move came in 1990 when Pope John Paul II returned the manuscript to its homeland and it now resides in the National Institute of Anthropology and History in Mexico City. As a result of these various moves the manuscript has had a series of different names: the Badianus Manuscript, Codex Barberini or Codex Badianus as well as the Aztec Herbal.

Herbs to treat [left to right] Burns and lignin strikes from the Codex badianus

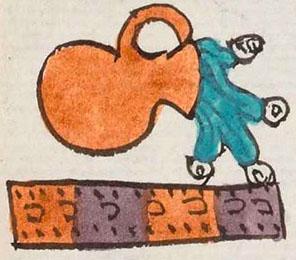

Most pages include at least one illustration of a plant mentioned in the text while a few pages are completely filled with drawings or occasionally just with text. Usually above each illustration, is the phonetic spelling of the Aztec name of the plant while Beneath is the Latin name of the disease or condition that the plant was used to treat. Descriptions in Latin of the plant’s use are written below.

Most pages include at least one illustration of a plant mentioned in the text while a few pages are completely filled with drawings or occasionally just with text. Usually above each illustration, is the phonetic spelling of the Aztec name of the plant while Beneath is the Latin name of the disease or condition that the plant was used to treat. Descriptions in Latin of the plant’s use are written below.

As you can easily see, the illustrations are not drawn from life so, if we’re being polite, they bear at best only a passing relation to what the plant actually looks liked. That’s no different to most early western herbals but it means that identification of the plants is often difficult if not actually impossible. In several cases, quite different illustrations are labeled with the same name.

From Book 10 of the Florentine Codex

Although there have been several attempts to identify the plants none have been that completely successful. In part that’s not surprising because Mexico has an estimated total of 25-30,000 species of plant. There are also problems of semantics in Nahuatl because it has obviously evolved from its 16th century form. There are currently about 30 linguistic variants but there were also several other languages being spoken in the Aztec empire so plant names could easily have come from those.

[If you are interested I knowing more about the plants that have been identified then Tucker and Janicks’s Flora of the Codex Cruz-Badianus [2020] is the best starting place while “Directions for Future Research by Alejandro de Avila in The Paper Museum of Cassiano del Pozzo, Series B part 8] is also worth a look, although be warned its heavy going, Given that the cheapest copy I’ve seen is £115 you’ll probably prefer to get it through the British Library or inter-library loans.

Herbs for [from left to right] polishing teeth; swollen gums; toothache; and heat of the throat from the Windsor copy

The same herbs from the original codex

So after all that – what’s actually in the book? It’s divided in 13 chapter each one of which deals with problems affecting various parts of the body, starting with the head in Chapter 1 which is concerned, according to one English translation, as “On the curation of the head, boils, scales of mange, coming out of the hair, lesion or broken skull”and then working downwards through the eyes, ears, nose, teeth, and so on down to chest, abdomen, bowel, groin, knees, until the feet are reached in chapter 8 . The subjects in Chapters 9 and 10 are more general, including fevers, wounds, haemorrhoids, “black blood”, and even “lightning stroke”. Chapter 11 focuses on female ailments, Chapter 12 on those of children, and the thirteenth and final chapter deals with “Of certain signs of one who is going to die”. All very jolly!

Herbs for the treatment of [left to right] angina, throat pain; dry throat from the Windsor Copy

The same herbs from the original codex

The specific remedies sound bizarre – although in actual fact are no more weird than many other medieval/early modern ones. I’m not joking when I tell you that for your headache you should eat onions in honey, and certainly not go to the public baths. If you are unfortunate enough to have contracted scabies then wash your head with urine. For a pain in the eye bind the eye of a fox to your upper arm and that will help wonderfully. No fox’s around? In that case you need to take the dust of a dead body, mix it with dragon’s blood and egg white and then apply freely. But if your eyes are only bloodshot then try sprinkling them with powdered human excrement. I’ll leave you to discover other remedies for yourself in one of the two English translations, by William Gates [1939] and Emily Walcott Emmart [1940] which are both easily available in-line.

From Book 10 of the Florentine Codex

Although like most European texts of the same kind and period the Aztec Herbal has little practical use but it documents an unbroken tradition of plant use that has persisted for centuries, and as we have seen with other contemporary discoveries of the innate truth behind ancient uses of plants it may well have potential for future use… if only someone could work out what the plants actually are!

For more information, the best general site on Aztec culture is Mexicolore which is an educational website run by a small team who providing in-school interactive history workshops on the Mexica (Aztecs). A search on JSTOR will reveal over 100o academic articles and references including Debra Hassig’s “Transplanted Medicine: Colonial Mexican Herbals of the Sixteenth Century” in RES:Anthropology and Aesthetics 1989; and Patrizia Grazieri, Huaxtepec: The Sacred Garden of an Aztec Emperor, via researchgate. Wikipedia has also some useful references and links, as does the website of Springer the publishers of Flora of the Codex Cruz-Badianus

From Book 10 of the Florentine Codex

You must be logged in to post a comment.