Peggy was one of the great figures of the social, scientific and horticultural circles of Georgian England. She was intelligent, curious about almost everything with a wide network of friends across all fields of knowledge but especially botany and other aspects of natural history. Of course it helped that she was born into a powerful aristocratic family and was, as the only child, immensely wealthy which enabled her not only to marry a Duke but indulge her interest in gardening and collect anything that took her fancy – from plants, to shells, art and antiquities.

In an age of great collectors she rivalled the greatest. So why isn’t she better known?

I suspect there’s a simple answer to that. We all know a picture is worth a thousand words and for whatever reason there are, as you will see, very few relevant images – but she’s still a fascinating character so please don’t give up!

She was born Lady Margaret Cavendish Harley in 1715 the daughter of Edward Harley, 2nd Earl of Oxford and his wife Lady Henrietta Cavendish Holles. She was clearly precocious with her mother writing “at three, Miss Peggy is of perfect health and wantonness and promises, as far as any lady of her years, to be an admirable coquette.”

She was bought up at Wimpole Hall in Cambridgeshire surrounded by her parens circle of friends who included plenty of politicians but also philosophers, poets, musicians and artists. She quickly became a favourite amongst them with the diplomat and poet Matthew Prior writing verses for ‘My noble, lovely, little Peggy’, when she was only 5.

Letters between her father and grandfather suggest she also fell in love with natural history especially plants at a very early age. She had art lessons from Bernard Lens, who also painted her portrait, while Rysbrack sculpted a bust of her aged about 12.

As a wealthy heiress her hand [and money] was wanted by many suitors but her parents were wary. In the end they accepted the offer of William Bentinck, second Duke of Portland (1709–1762).

He was the grandson of Hans William Bentinck, 1st Earl of Portland, William III’s friend and Superintendent of the Royal Gardens in the 1690s, chosen because he was thought to be a safe bet and the candidate least likely to run up unmeetable debts or indulge in vices. Her parents chose well and the couple had a long and happy marriage – in letters to friends, she called her husband affectionately ‘True Blue’ or ‘Sweet William.’ They were to have six children including one who became prime minister.

The couple had a town house in Whitehall and a large country estate at Bulstrode in Buckinghamshire and it was there that Peggy spent the greater part of her adult life, 27 years with William and then 23 more as a widow, devoting her energy to developing the house, park and gardens as well as amassing her various collections. Known collectively as the Portland Museum they are thought to have been the largest in Britain, and possibly in Europe, at the time even exceeding those of Sir Hans Sloane which were later to form the basis of the British Museum.

Detail showing the north front of the Old Hall.

The original house at Bulstrode as seen in John Fisher’s estate map of 1686, was bought in 1676 and then extended by the infamous Judge Jeffreys.

The original house at Bulstrode as seen in John Fisher’s estate map of 1686, was bought in 1676 and then extended by the infamous Judge Jeffreys.

After his fall it was bought by William’s grandfather, the 1st Earl of Portland who is thought to have commissioned William Talman to add pavilions and terraces to the south front although the house itself was not altered very much. An orangery was built and formal gardens laid out probably by the same team who worked for William III at Hampton Court and elsewhere. This would have included not only George London but also Claude Desgots the French parterre designer, and perhaps even Henry Wise.

Work continued under his son who was created first Duke of Portland in 1716, and the estate can be seen in two engravings in Vitruvius Britannicus (1734). Research has shown that many of the features were actually created and indeed some are still visible notably the Long Canal [on the left] and the lines of hedges, avenues and boundaries.

In the 1740s, the ducal couple commissioned the architect and builder Stiff Leadbetter to alter the house more significantly. Peggy’s great friend Mary Delany, [of whom more later] noted in 1756 that “Bulstrode is greatly improved; the old apartments below new floored and furnished, and many alterations in hand within and without doors” These included the long horseshoe-shaped walk in front of the house “with great slopes and a place in the the bottom for water” being “all thrown down, and a lawn substituted in its place, [to] open a very fine and agreeable view to the house”. She had a ha-ha dug, created other vistas and began a programme of tree planting.

Garden buildings in various styles including a Turkish tent [no images survive] went up and the Duchess enlarged the aviary and menagerie which had been started by her father-in-law the first Duke. Mrs Delany commented that “The Dss is as eager on collecting animals as if she foresaw another deluge and was assembling every creature after its kind to preserve the species.”

That phrase is telling because while we know the natural history was a popular amusement for aristocratic ladies in the 18th century the Duchess did not see it as a pastime but something much more serious. In particular she became deeply immersed in the world of plants, cultivating the friendship of plantsmen such as Philip Miller, the long-serving director of Chelsea Physic Garden, Peter Collinson, the collector who had strong links with north America, and William Curtis, who later founded the Botanical Magazine. She knew Hans Sloane, and Aylmer Lambert the founding member of the Linnaean Society. She also knew Lord Bute, keen plantsman and Prime Minister 1762-3, who was probably instrumental in designing the royal gardens at Kew, as well as William Aiton who was to be the director of Kew under the supervision of Joseph Banks.

She extended her patronage to artists notably the greatest botanical illustrator of the day, Georg Dionysius Ehret (1708–1770), who was Miller’s brother-in-law. He was to make hundreds of drawings for her as well as giving drawing lessons to her daughters. Amongst her other connections were the wonderful rococo artist Thomas Robins and his sons, to whom she was introduced by Henry Seymer, a fellow and ‘rival’ shell collector. She also commissioned James Bolton, who was later to produce important books on ferns and fungi, early in his career to produce drawings of her natural history collection, and encouraged her own gardener John Agnew who was to become a talented natural history illustrator as well as talented horticulturist.

In the light of this it’s both surprising and disappointing that there are almost no surviving images of the gardens at Bulstrode.

For more on the Duchess’s connections with Robins see Cathryn Spence’s article “Thomas Robins and the Dorset Sketches” in the Georgian Group Journal 2013.

Bulstrode Park: drawing of the house from the south-east by Grimm, 1781. Image: British Library.

The Duchess’s network extended overseas too. She recognised the importance of Carl Linnaeus published his proposals for new taxonomic system, Systema Plantarum, in 1753 and invited his pupil Daniel Solander, to Bulstrode soon after his arrival from Sweden in 1760. It was a useful contact because he was to accompany Joseph Banks and James Cook on their exploration of the `Pacific in 1768. Solander even stayed in touch with her writing letters from Endeavour on the voyage.

As a result she was amongst the first to see the horticultural spoils that he and Banks had bought back when they both visited Bulstrode in 1771 after their return. A letter from Mrs Delany recalled them giving the duchess seeds which were apparently planted in ‘Botany Bay field’.

In all of this Peggy was helped by Rev John Lightfoot, the curate at nearby Uxbridge and a keen amateur naturalist. Appointed the family chaplain by the Duke he also acted as their librarian. Elected a member of the Royal Society, he corresponded with Linnaeus and travelled throughout Britain -collecting plants and helping her create an herbarium.

For more on Lightfoot see Jean Bowden, John Lightfoot: his work and travels, 1991)

But the Duchess didn’t leave it all to others and travelled widely in Britain herself. On one of these plant-hunting trips, to the Peak District in the autumn of 1766, she was joined by none other than Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the Swiss-French philosopher and writer. She had been introduced to him by Mary Delany’s brother who lived near Wootton Hall, Northampton, where Rousseau spent time in 1766-67.

Although Mrs Delany herself wouldn’t meet such a radical, the Duchess did and later corresponded with him, sending him plants and books including William Mason’s English Garden. He replied “I am bound to like the subject, having been the first on the Continent to celebrate and transmit these very gardens,” and terming himself “l’herboriste de Madama la duchess de Portland.” It’s extraordinary because although elsewhere Rousseau denied female scientific talent for science, he acknowledged that his own knowledge of natural history, was inferior to that of the Duchess. .

For more on this unlikely pairing see Alexandra Cook’s article “Botanical exchanges: Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the Duchess of Portland”, in History of European Ideas, June 2007

Elite society in Georgian Britain was closely knit and its members were aware of what the Duchess was doing at Bulstrode, as correspondence demonstrate. One of her longest-standing friends was Elizabeth Robinson better known as Mrs Montagu, the leading bluestocking who was also working on improvements to her own estate at Sandleford Priory. She wrote to another friend, after a stay at Bulstrode that “the rural beauties of this place would persuade [sic] me that I was in the plains of Arcadia.” while “the menagerie was the finest in England”. William Curtis of the Botanical Magazine, thanked the Duchess for “many scarce, valuable plants, both British and foreign” while Mrs Lybbe Powys, a great letter writer and traveller remarked “Her Grace is exceedingly fond of gardening, is a very Learned botanist, and has every English plant in the garden by themselves.”

For more on the friendship and correspondence between the two see the “Elizabeth Montagu Correspondence Online project” run by Swansea University

Mary Delany by Zincke, c.1740

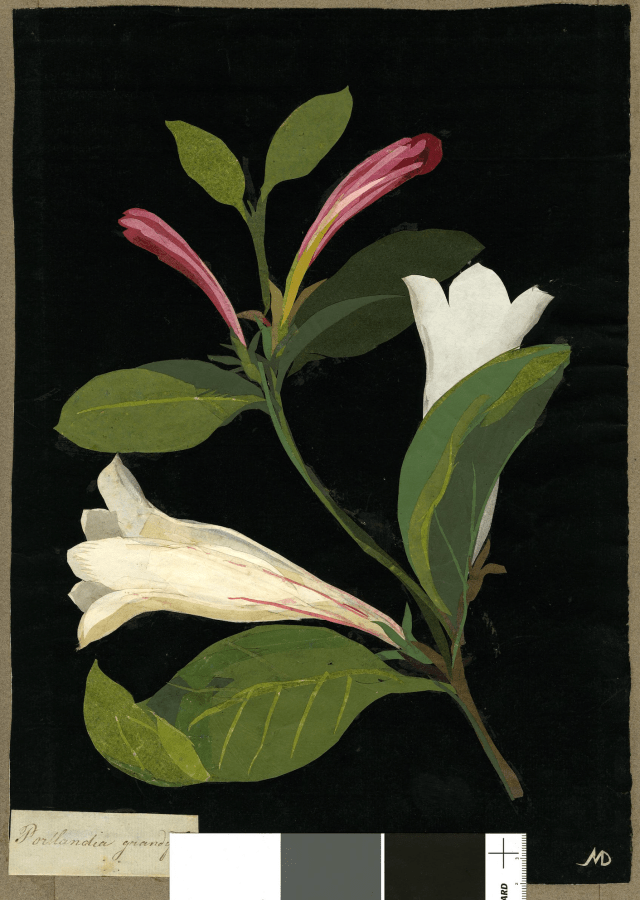

Another of her lifelong friends was Mary Delany who was about 15 years older and initially a friend of her mother. Luckily she too was a great correspondent and it is partly from her letters that we have so much detail about Bulstrode even if we don’t have many pictures. The two women shared many interests, obviously including plants but whereas the Duchess saw them with a scientific eye Mrs Delany saw them with that of an artist. After the death of the Duke in 1762 and of her own husband in 1768, Mrs Delany spent every summer at Bulstrode, and it was there that in 1772 she devised her method of making what she called “paper mosaiks” of flowers, which eventually made up the Flora Delanica now in the British Museum. [See this earlier post for more on that] The last she completed was Portlandia grandiflora, but I wondered why there are no collages of the Portland Rose which it’s often reported was named in Peggy’s honour.

A quick Google search suggested a whole range of potential origins for the Portland Rose group, important because it was the earliest to reliably repeat flower, including that the Duchess raised it at Bulstrode. After spending an hour scrolling through websites which copied each other’s mistakes, I finally found one which seemed trustworthy: the Historic Roses Group website which carries an article by Peter Harkness on repeat-flowering old roses including a section on “The Mystery of the Portland Rose”. He carried out a serious detective-like analysis of every early mention and concludes that “seeking to nail down facts about it is like handling mercury.” But, in short, the upshot was that it was actually unlikely to be connected with the Duchess.

Bulstrode Park: drawing of the grotto by Grimm, 1781. : British Library.

In June 1770 the Duchess and Mrs Delany went to Strawberry Hill and a few days later, Horace Walpole returned the visit. G0thick was suddenly the order of the day at Bulstrode with apparently plans to transform the house into a Gothic mansion. The Duchess began in a small way by having a grotto built at one end of the Long Water. Mrs Delany supervised the work; she says that ‘the stones were ruder than Gothic and the stone-mason’s head harder than the stones he hammers’. Mrs Delany then decorated the interior with shell work.

Shells were another of Peggy’s particular interest and she built up an enormous collection often paying people such as Dr. Thomas Shaw who was given £600 “to fund his travels and to find shells and curiosities for her as he travelled”. She had at least one book about shells dedicated to her and Peter Dance in his “Shell Collecting: An Illustrated History” states that “She became the unchallenged leader of British dilettanti and her collection of shells was considered the finest in England and rivalled the best in Europe.”

For more on this see The Duchess’s Shells: Natural History Collecting In The Age Of Cook’s Voyages. Beth Fowkes Tobin. 2014

The duchess died at Bulstrode after a short illness on 17 July 1785 and everything passed to her elder son, the third Duke with instructions to sell her entire natural history collection and many other objects for the benefit of her other children. A catalogue was drawn up by Lightfoot which included many unnamed specimens: ‘It was the intention of the enlightened possessor to have had unknown [sic] species described and published … but it pleased God to shorten her design.’ The frontispiece shows a wonderful jumble of objects centred around the ancient Roman glass vase – which she had bought in 1784 and which became known as the Portland Vase.

For more on the vase and the story behind its acquisition by the Duchess – and Horace Walpole’s cruel description of her as ‘a simple woman, but perfectly sober, and intoxicated only by empty vases’ see the notes on the British Museum’s website.

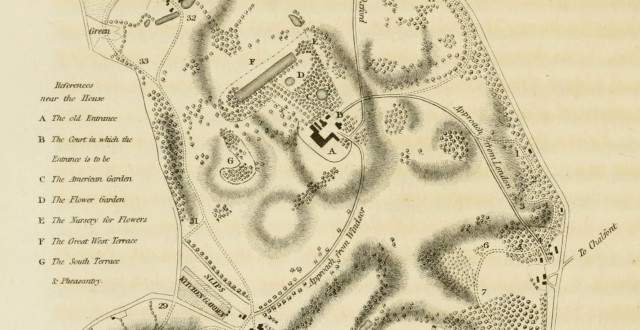

The new Duke was later to commission James Wyatt to modernise the old house, but in 1793 before the building work was begun, the Duke called in Humphry Repton to remodel the park at Bulstrode as well as his other main seat at Welbeck Abbey. It was one of Repton’s earliest commissions and the Duke was to become one of his biggest patrons, employing him on an annual retainer, and introducing him to many of his friends.

Repton was to write at some length about Bulstrode Park in his Observations praising its beauty and using it as an example of how parks should be laid out. While he is usually thought to have done a lot of work there, more recent research suggests that in fact much of what he described was already in place, and probably organised by the Duchess.

For more on Repton, Bulstrode and the third Duke see Sarah Rutherford’s Report on the Bucks Gardens Trust Research and Recording Project 2017-2018 and Mick Thompson’s Humphry Repton and the Development of the Flower Garden in Garden History, 2019.

Unfortunately the Duke died broke in 1809 and the unfinished estate was sold to the Duke of Somerset and in the early 1860s demolished apart from Wyatt ‘s tower. It was replaced by a Gothic heap now listed at Grade 2. The parkland and gardens despite many alterations are Grade II*. In 2017 there were plans to turn Bulstrode into an upmarket hotel but I can find no sign that this has been done so if anyone knows its fate please let me know.

The Duchess’s story is a wonderful example of how beauty and intellect can come together, showing how passion can serve culture and knowledge. We’re pleased to highlight such figures who have left a lasting human impact.

A fascinating life and legacy; thank you so much for shining some light on another female who deserves much better recognition.